The Battle of Longanus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PYRRHUS Imperator Campaign of Italy and Sicily, 279 BCE to 275 BCE

PYRRHUS IMPERATOR CAMPAIGN OF ITALY AND SICILY, 279 BCE TO 275 BCE Pyrrhus Imperator simulates the campaign of It indicates the maximum number of combat units Pyrrhus 1st king of Epirus in Greece from 279 (4 to 10) that may be commanded by this comman- to 275 BCE. One player commands the eastern der. This is a roman numeral for the Romans and camp: Epirotes, Samnites, Etruscans and Greeks; an Arabic numeral for the others. the other player commands the western camp: • Verso : the commander has been activated this Romans and Carthaginians. The Campanians and season. Mamertines are neutral. •Consuls A and B : The rules are inspired by Optimus Princeps (VV 67, The consuls are called A and B to differentiate them 68, 69), Spartacus Imperator (Hexasim) and Caesar in the game help. They have no activated verso.. Imperator: Britannia (VV 112). Note : A Roman commander cannot command a mercenary CU. 0 - MATeRIeL 0.1 - THe GAMe BOARD 0.2.2 - The combat units (CU) The game board represents a point in Africa but es- A combat unit (CU) represents a unit of 500 to pecially in Magna Graecia, which is the southern 2,000 men or 500 to 1,000 cavaliers part of Italy and Sicily. The small islands are deco- or 10 war elephants or 10 siege wea- rative elements. pons. A CU has a melee value of 0 to The zones may be rural zones (plains are green, 3 and a fire value of 0 to 4. mountains are brown), sea zones (blue), or urban The Roman CU have a symbol: or city zones (squares). -

Sicilian Landscape As Contested Space in the First Century BC: Three Case Studies

Sicilian Landscape as Contested Space in the First Century BC: Three Case Studies Dustin Leigh McKenzie BA (Hons), Dip. Lang. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry ii Abstract Sicily was made the first overseas Roman province between 241 and 212 BC, and became known as the ‘bread-basket’ of the Republic due to the island’s famously fertile farmlands. The island, with its history of pre-Roman conflict, second century slave revolts, and use as a military stronghold in the civil wars of the first century, never dissociated itself from conflict. As such, its construction as a ‘contested space’ was popular in the literature of first-century Rome, employed as a symptomatic topos of the state of Rome – the closer Roman Sicily resembled its pre- annexation state, the greater the perceived threat to the Republic, and vice-versa. This construction of Sicily and its landscape was employed by authors such as Cicero, Diodorus Siculus, and Virgil to great effect, as they engaged with, reinforced, or challenged the major contemporary discourses of imperialism, the impact of civil war, and food security. Cicero’s In Verrem presents its audience with a Sicily that has been purposely constructed to deliver the most damning image of Verres, the infamously corrupt governor of Sicily from 73-71, the most sympathetic and familiar image of the Sicilians, presented as virtuous and stoic farmers, and a Sicily that has been reduced to a war-torn desert under Verres’ rule. Through his construction of Sicily as contested space, Cicero secured his win against Verres in court and demonstrated to his audiences the danger Verres’ actions presented Rome, threatening the stability of the relationship between Sicily and Rome. -

Quod Omnium Nationum Exterarum Princeps Sicilia

Quod omnium nationum exterarum princeps Sicilia A reappraisal of the socio-economic history of Sicily under the Roman Republic, 241-44 B.C. Master’s thesis Tom Grijspaardt 4012658 RMA Ancient, Medieval and Renaissance Studies Track: Ancient Studies Utrecht University Thesis presented: June 20th 2017 Supervisor: prof. dr. L.V. Rutgers Second reader: dr. R. Strootman Contents Introduction 4 Aims and Motivation 4 Structure 6 Chapter I: Establishing a methodological and interpretative framework 7 I.1. Historiography, problems and critical analysis 7 I.1a.The study of ancient economies 7 I.1b. The study of Republican Sicily 17 I.1c. Recent developments 19 I.2. Methodological framework 22 I.2a. Balance of the sources 22 I.2b. Re-embedding the economy 24 I.3. Interpretative framework 26 I.3a. Food and ideology 27 I.3b. Mechanisms of non-market exchange 29 I.3c. The plurality of ancient economies 32 I.4. Conclusion 38 Chapter II. Archaeology of the Economy 40 II.1. Preliminaries 40 II.1a. On survey archaeology 40 II.1b. Selection of case-studies 41 II.2. The Carthaginian West 43 II.2a. Segesta 43 II.2b. Iatas 45 II.2c. Heraclea Minoa 47 II.2d. Lilybaeum 50 II.3. The Greek East 53 II.3a. Centuripe 53 II.3b. Tyndaris 56 II.3c. Morgantina 60 II.3d. Halasea 61 II.4. Agriculture 64 II.4a. Climate and agricultural stability 64 II.4b. On crops and yields 67 II.4c. On productivity and animals 70 II.5. Non-agricultural production and commerce 72 II.6. Conclusion 74 Chapter III. -

Sicily and the Imperialism of Mid-Republican Rome : (289-191BC)

SICILY AND THE IMPERIALISM OF MID- REPUBLICAN ROME : (289-191BC) John Serrati A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2001 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11102 This item is protected by original copyright L Sicily and the Imperialism of mid-Republican Rome (289-191 BC) John Serrati Ph.D. Ancient History 19 January 2001 i) I, John Serrati, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 96,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Signature of Candidate ii) I was admitted as a research student in October 1995 and as a candidate for the degreeofPh.D. in Ancient History in October 1996; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between 1995 and 2001. iii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree ofPh.D. in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. F:-·;T,',,:.-~TD Signature of Supervisor ... .tt,"·.· .:.:.~~::;.L~~J Date ..I.'1.b.J~.~ .. "'"-...... .,r-'" In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

The Beginning of the First Punic War and the Concept of Italia Federico

THE BEGINNING OF THE FIRST PUNIC WAR AND THE CONCEPT OF ITALIA Federico Russo* 1. Introduction The beginning of the first Punic War was the centre of a historiographic debate already in ancient times, mainly in relation to the legitimacy of the Roman intervention in Messina. Here, the Mamertines, who were under siege by the Syracusans, had split into two factions: one pro-Roman and the other pro-Punic.1 Some of them appealed to the Carthaginians, proposing to put themselves and the citadel into their hands, while others sent an embassy to Rome, offe- ring to surrender the city and begging for assistance as a kindred people (καὶ δεόμενοι βοηθήσειν σφίσιν αὐτους ὁμοφύλοις ὑπάρχουσιν). The Romans were long at a loss, the succour demanded being so obviously unjustifiable. For they had just inflicted on their own fellow-citizens the highest penalty for their treachery to the people of Rhegium, and now to try to help the Mamer- tines, who had been guilty of like offence not only at Messene but at Rhegium also, was a piece of injustice very difficult to excuse. But fully aware as they were of this, they yet saw that the Carthaginians had not only reduced Libya to subjection, but a great part of Spain besides, and that they were also in possession of all the islands in the Sardinian and Tyrrhenian Seas. They were therefore in great apprehension lest, if they also became masters of Sicily, they would be most troublesome and dangerous neighbours, hemming them in on all sides and threatening every part of Italy. -

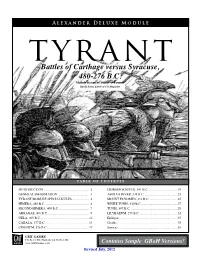

Battles of Carthage Versus Syracuse, 480-276 B.C. Module Design by Daniel A

Tyrant Alexander Deluxe Module tyrant Battles of Carthage versus Syracuse, 480-276 B.C. Module Design by Daniel A. Fournie GBoH Series Editor of C3i Magazine T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 CRIMISSOS RIVER, 341 B.C. ................................... 19 GENERAL INFORMATION ...................................... 3 ABOLUS RIVER, 338 B.C. ........................................ 23 TYRANT MODULE SPECIAL RULES..................... 3 MOUNT ECNOMUS, 311 B.C. .................................. 25 HIMERA, 480 B.C. ..................................................... 4 WHITE TUNIS, 310 B.C. ............................................ 27 SECOND HIMERA, 409 B.C. .................................... 7 TUNIS, 307 B.C. ......................................................... 29 AKRAGAS, 406 B.C. .................................................. 9 LILYBAEUM, 276 B.C. .............................................. 32 GELA, 405 B.C............................................................ 12 Epilogue ....................................................................... 35 CABALA, 377 B.C. ..................................................... 14 Credits .......................................................................... 35 CRONIUM, 376 B.C. .................................................. 17 Sources ......................................................................... 36 GMT GAMES P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com Contains Simple GBoH Versions! -

Picturesque and Noisy, Catania Is the City Of

The infinite island gorges formed by erosion by water. Lastly, the Lastly, bywater. formedbyerosion gorges deeply carvedoutby rock, above allcalcareous sion oftablelands formedbylava,tufaand isasucces- the easternpartofisland,there mountains ofCalabria.Furthersouth, againin the Peloritanscontinue,wholly similar tothe lowhills. dominating roundish formations,isolatedoringroups, calcareous theMadoniegivewaytoirregular river Torto, Justwestof the peaks goupto2000metres. andtheMadoniemountains, whose Nebrodi ofthePeloritans, isastretch west, there biggest oneinEurope. volcano, 3300m.high,isactive,andthe The park),intheeasternpartofSicily. nature byabig ofwhichisprotected (the wholearea Catania. withonlyonebigplainnear and hilly, Sicilian landscape:theislandismountainous movementinthe isgreat 1000 km.long.There tothenorth,andsandysouth,is rocky Itscoast,prevalently metres). er 25,708square the southPelagieandPantelleria(altogeth- Islands andUstica,tothewestEgadi, smaller islands:tothenorthAeolian isa seriesof itthere Around metres). square Sicily isthebiggestislandinlatter(25,460 To theeast,between Messina andEtna, To eastto Along thenortherncoast,from The mostimportantmassifistheEtnaone oftheMediterranean, Placed atthecentre Geography andgeology terrible. magnificentand darkandsunny, an island",mythologicalandconcrete, identities" (Bufalino). and,toboot,apluralnation, withsomanydifferent rather thanaregion ious tobeintegratedinthemodernworldandtimes,"anation at oncepoorandrich,closeddiffidentinitsnobledecadenceyetsoanx- yetstilltodayitisworthknowingit,thisSicilywithathousandfaces, -

Social Struggles of Early Rome 753-121 B.C.E. Philip John Porta a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Salisbury Univers

Social Struggles of Early Rome 753-121 B.C.E. Philip John Porta A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate Faculty of Salisbury University In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Salisbury, Maryland February, 2016 Philip JohnPorta This project for the M.A. degree in History has been approved forthe HistoryDepartment by Theses Director Department Chair 2/29/16 Abstract This thesis is a short history of the social struggles of the Roman nation from the beginning of the Monarchy until the times of Julius Caesar in the late Republic. Some of the topics enclosed concern with the establishment of the Republic after the Monarchy, the creation and explanation of the offices of the Republic, the process of the Conflict of the orders, the class conflict between the patricians and the plebeians, and the creation of the Roman constitution. Other topics look at the expansion of Rome across the Mediterranean world through conquest during the Italian, Punic, Macedonian, and Seleucid Wars and how these events shaped the Roman government and social relations between the patricians and plebeians, as well as how the two classes came together during these times of crisis. The latter part of the paper deals with the rise of the Gracchi and the Roman Revolution, and how these events shaped the late Republic and allowed the rise of political figures such as Sulla, Marius, and Caesar. The conclusion finishes with the wrap up of the paper, as well as giving the reader a few small glimpses into the events after the Gracchan revolution. Introduction Rome: the name of this ancient civilizations city inspires thoughts of grandeur, imperial might, military conquest, and tales of tragedy. -

The Punic Wars ( 264 BCE to 146 BCE)

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2019 Cause, Course, and Consequence: The Punic aW rs (264 BCE to 146 BCE) Angela Coco [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation Coco, Angela, "Cause, Course, and Consequence: The unicP Wars (264 BCE to 146 BCE)" (2019). Honors Thesis Collection. 645. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/645 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cause, Course, and Consequence: The Punic Wars ( 264 BCE to 146 BCE) Angela Anne Coco A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in History At Wellesley College Under the advisement of Professor Guy M. Rogers April 2019 © 2019 Angela Coco Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the support and forbearance of a number of people and institutions. Thank you to Wellesley College for giving me the opportunity to create this work and for embracing me throughout my time here. Thank you to the Samuel and Hilda Levitt Foundation and The F.A.O Schwarz Foundation for funding my research and travel throughout Sicily. I would especially like to recognize and thank my incredible advisor and mentor, Professor Guy M. Rogers. I am infinitely thankful for his hard work, edits, encouragement, direction, and knowledge on this project and in general. -

An Archaeological History of Carthaginian Imperialism

An Archaeological History of Carthaginian Imperialism Nathan Pilkington Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ©2013 Nathan Pilkington All rights reserved ABSTRACT An Archaeological History of Carthaginian Imperialism Nathan Pilkington Carthage is the least understood imperial actor in the ancient western Mediterranean. The present lack of understanding is primarily a result of the paucity of evidence available for historical study. No continuous Carthaginian literary or historical narrative survives. Due to the thorough nature of Roman destruction and subsequent re-use of the site, archaeological excavations at Carthage have recovered only limited portions of the built environment, material culture and just 6000 Carthaginian inscriptions. As a result of these limitations, over the past century and half, historical study of Carthage during the 6th- 4th centuries BCE traditionally begins with the evidence preserved in the Greco-Roman sources. If Greco-Roman sources are taken as direct evidence of Carthaginian history, these sources document an increase in Carthaginian military activity within the western Mediterranean during the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. Scholars have proposed three different dates for the creation of the Carthaginian Empire from this evidence: c. 650, c.550 or c. 480 BCE. Scholars have generally chosen one of these dates by correlating textual narratives with ‘corroborating’ archaeological evidence. To give an example, certain scholars have argued that destruction layers visible at Phoenician sites in southwestern Sardinia c. 550-500 represent archaeological manifestations of the campaigns of Malchus and Mago’s sons recorded in the sources. -

The Historians' Portrayal of Bandits, Pirates, Mercenaries and Politicians

Freelance Warfare and Illegitimacy: the Historians’ Portrayal of Bandits, Pirates, Mercenaries and Politicians A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Minnesota BY Aaron L. Beek In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advised by Andrew Gallia April 30, 2015 © Aaron L. Beek 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines freelance warfare in the ancient world. The ‘freelancer’ needs to be understood as a unified category, not compartmentalized as three (or more) groups: pirates, bandits, and mercenaries. Throughout, I contend that ancient authors’ perception and portrayal of the actions of freelancers dramatically affected the perceived legitimacy of those actions. Most other studies (e.g. Shaw 1984, de Souza 1999, Grünewald 1999, Pohl 1993, Trundle 2004, Knapp 2011) focus on ‘real’ bandits and on a single one of these groups. I examine these three groups together, but also ask what semantic baggage words like latro or leistes had to carry that they were commonly used in invectives. Thus rhetorical piracy is also important for my study. The work unfolds in three parts. The first is a brief chronological survey of ‘freelance men of violence’ of all stripes down to the second century BC. Freelancers engage in, at best, semi-legitimate acts of force. Excluded are standing paid forces and theft by means other than force, vis. In a form of ancient realpolitik, the freelancer was generally more acceptable to states than our aristocratic historians would prefer that we believe. Moreover, states were more concerned with control of these ‘freelancers’ than in their elimination. The second section explains events of the second and first century in greater detail. -

Rebel Motivations During the Social War and Reasons For

REBEL MOTIVATIONS DURING THE SOCIAL WAR AND REASONS FOR THEIR ACTIONS AFTER ITS END A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By MARK LOUIS HOWARD B.A., Brigham Young University-Idaho, 2014 2019 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL October 10th, 2019 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY MARK LOUIS HOWARD ENTITLED REBEL MOTIVATIONS DURING THE SOCIAL WAR AND REASONS FOR THEIR ACTIONS AFTER ITS END BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. __________________________ ___ Rebecca Edwards, Ph.D. Thesis Director __________________________ ___ Valarie Stoker, Ph.D. Chair, Religion, Philosophy, and Classics Committee on Final Examination: ________________________________ Rebecca Edwards, Ph.D. ________________________________ Bruce Laforse, Ph.D. ________________________________ Jeanette Marchand, Ph.D. ________________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Howard, Mark Louis. M.Hum. Department of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics, Master of Humanities Graduate Program, Wright State University, 2019. Rebel Motivations During the Social War and Reasons for Their Actions After Its End. Modern scholarship has fiercely contested the motivations of Italian rebels during the Social War. Generally speaking, three camps have formed concerning this issue: those who strictly follow the sources in arguing that the allies fought against Rome to obtain full citizenship under her rule, those who believe the rebels sought independence rather than citizenship, and those who believe that rebel actions were inspired by differing motivations. By building upon the scholarship of Dart and Salmon, I believe we will see that many of the allies were willing to fight against the empire for a place of privilege within it.