Novel Intrinsic and Extrinsic Approaches to Selectively Regulate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Figure 1. Vimentin

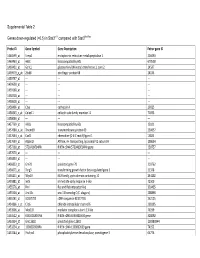

Double mutant specific genes Transcript gene_assignment Gene Symbol RefSeq FDR Fold- FDR Fold- FDR Fold- ID (single vs. Change (double Change (double Change wt) (single vs. wt) (double vs. single) (double vs. wt) vs. wt) vs. single) 10485013 BC085239 // 1110051M20Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1110051M20 gene // 2 E1 // 228356 /// NM 1110051M20Ri BC085239 0.164013 -1.38517 0.0345128 -2.24228 0.154535 -1.61877 k 10358717 NM_197990 // 1700025G04Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700025G04 gene // 1 G2 // 69399 /// BC 1700025G04Rik NM_197990 0.142593 -1.37878 0.0212926 -3.13385 0.093068 -2.27291 10358713 NM_197990 // 1700025G04Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700025G04 gene // 1 G2 // 69399 1700025G04Rik NM_197990 0.0655213 -1.71563 0.0222468 -2.32498 0.166843 -1.35517 10481312 NM_027283 // 1700026L06Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700026L06 gene // 2 A3 // 69987 /// EN 1700026L06Rik NM_027283 0.0503754 -1.46385 0.0140999 -2.19537 0.0825609 -1.49972 10351465 BC150846 // 1700084C01Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700084C01 gene // 1 H3 // 78465 /// NM_ 1700084C01Rik BC150846 0.107391 -1.5916 0.0385418 -2.05801 0.295457 -1.29305 10569654 AK007416 // 1810010D01Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1810010D01 gene // 7 F5 // 381935 /// XR 1810010D01Rik AK007416 0.145576 1.69432 0.0476957 2.51662 0.288571 1.48533 10508883 NM_001083916 // 1810019J16Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1810019J16 gene // 4 D2.3 // 69073 / 1810019J16Rik NM_001083916 0.0533206 1.57139 0.0145433 2.56417 0.0836674 1.63179 10585282 ENSMUST00000050829 // 2010007H06Rik // RIKEN cDNA 2010007H06 gene // --- // 6984 2010007H06Rik ENSMUST00000050829 0.129914 -1.71998 0.0434862 -2.51672 -

Inherited Monogenic Defects of Ceramide Metabolism Molecular

Clinica Chimica Acta 495 (2019) 457–466 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinica Chimica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cca Review Inherited monogenic defects of ceramide metabolism: Molecular bases and diagnoses T ⁎⁎ Patricia Dubota,b, Frédérique Sabourdya,b, Jitka Rybovac,Jeffrey A. Medinc,d, , ⁎ Thierry Levadea,b, a Laboratoire de Biochimie Métabolique, Centre de Référence en Maladies Héréditaires du Métabolisme, Institut Fédératif de Biologie, CHU de Toulouse, Toulouse, France b INSERM UMR1037, CRCT (Cancer Research Center of Toulouse), Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France c Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA d Department of Biochemistry, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA ABSTRACT Ceramides are membrane lipids implicated in the regulation of numerous biological functions. Recent evidence suggests that specific subsets of molecular species of ceramide may play distinct physiological roles. The importance of this family of molecules in vertebrates is witnessed by the deleterious consequences of genetic alterations in ceramide metabolism. This brief review summarizes the clinical presentation of human disorders due to the deficiency of enzymes involved either in the biosynthesis or the degradation of ceramides. Information on the possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms is also provided, based on knowledge gathered from animal models of these inherited rare conditions. When appropriate, tools for chemical and molecular diagnosis of these disorders and therapeutic options are also presented. 1. Introduction/foreword relationships that are relevant for unraveling the biological role of these genes and gene products in humans. Studies on ceramides and sphingolipid metabolism have attracted a lot of attention recently. This is largely related to the multiplicity of 2. -

1General Introduction and Outline Glycosphingolipids, Carbohydrate

Lipophilic iminosugars : synthesis and evaluation as inhibitors of glucosylceramide metabolism Wennekes, T. Citation Wennekes, T. (2008, December 15). Lipophilic iminosugars : synthesis and evaluation as inhibitors of glucosylceramide metabolism. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13372 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13372 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). General Introduction and Outline Glycosphingolipids, Carbohydrate- 1 processing Enzymes and Iminosugar Inhibitors General Introduction The study described in this thesis was conducted with the aim of developing lipophilic iminosugars as selective inhibitors for three enzymes involved in glucosylceramide metabolism. Glucosylceramide, a β-glycoside of the lipid ceramide and the carbohydrate d-glucose, is a key member of a class of biomolecules called the glycosphingolipids (GSLs). One enzyme, glucosylceramide synthase (GCS), is responsible for its synthesis and the two other enzymes, glucocerebrosidase (GBA1) and β-glucosidase 2 (GBA2), catalyze its degradation. Being able to influence glucosylceramide biosynthesis and degradation would greatly facilitate the study of GSL functioning in (patho)physiological processes. This chapter aims to provide background information and some history on the various subjects that were involved in this study. The chapter will start out with a brief overview of the discovery of GSLs and the evolving view of the biological role of GSLs and carbohydrate containing biomolecules in general during the last century. Next, the topology and dynamics of mammalian GSL biosynthesis and degradation will be described with special attention for the involved carbohydrate-processing enzymes. -

Sphingolipid Metabolism Diseases ⁎ Thomas Kolter, Konrad Sandhoff

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1758 (2006) 2057–2079 www.elsevier.com/locate/bbamem Review Sphingolipid metabolism diseases ⁎ Thomas Kolter, Konrad Sandhoff Kekulé-Institut für Organische Chemie und Biochemie der Universität, Gerhard-Domagk-Str. 1, D-53121 Bonn, Germany Received 23 December 2005; received in revised form 26 April 2006; accepted 23 May 2006 Available online 14 June 2006 Abstract Human diseases caused by alterations in the metabolism of sphingolipids or glycosphingolipids are mainly disorders of the degradation of these compounds. The sphingolipidoses are a group of monogenic inherited diseases caused by defects in the system of lysosomal sphingolipid degradation, with subsequent accumulation of non-degradable storage material in one or more organs. Most sphingolipidoses are associated with high mortality. Both, the ratio of substrate influx into the lysosomes and the reduced degradative capacity can be addressed by therapeutic approaches. In addition to symptomatic treatments, the current strategies for restoration of the reduced substrate degradation within the lysosome are enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), cell-mediated therapy (CMT) including bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and cell-mediated “cross correction”, gene therapy, and enzyme-enhancement therapy with chemical chaperones. The reduction of substrate influx into the lysosomes can be achieved by substrate reduction therapy. Patients suffering from the attenuated form (type 1) of Gaucher disease and from Fabry disease have been successfully treated with ERT. © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Ceramide; Lysosomal storage disease; Saposin; Sphingolipidose Contents 1. Sphingolipid structure, function and biosynthesis ..........................................2058 1.1. -

The Neutral Glycosphingolipid Globotriaosylceramide Promotes Fusion Mediated by a CD4-Dependent CXCR4-Utilizing HIV Type 1 Envelope Glycoprotein

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 14435–14440, November 1998 Medical Sciences The neutral glycosphingolipid globotriaosylceramide promotes fusion mediated by a CD4-dependent CXCR4-utilizing HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein ANU PURI*, PETER HUG*, KRISTINE JERNIGAN*, JOSEPH BARCHI†,HEE-YONG KIM‡,JILLON HAMILTON‡, i JOE¨LLE WIELS§,GARY J. MURRAY¶,ROSCOE O. BRADY¶, AND ROBERT BLUMENTHAL* *Section of Membrane Structure and Function, Laboratory of Experimental and Computational Biology, Division of Basic Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, MD 21702; †Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Division of Basic Sciences, National Cancer Institute and ¶Developmental and Metabolic Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; ‡Laboratory of Membrane Biochemistry and Biophysics, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD 20852; and §Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unite´Mixte de Recherche 1598, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif Cedex 94805, France Contributed by Roscoe O. Brady, September 25, 1998 ABSTRACT Previously, we showed that the addition of enabling individual HIV strains to choose between alternate human erythrocyte glycosphingolipids (GSLs) to nonhuman modes of entry into cells. CD41 or GSL-depleted human CD41 cells rendered those cells The GSL hypothesis is based on a number of observations, susceptible to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated cell fu- including recovery of fusion of nonsusceptible cells after sion. Individual components in the GSL mixture were isolated transfer of protease- and heat-resistant components from by fractionation on a silica-gel column and incorporated into human erythrocytes (12, 13), physicochemical studies on the the membranes of CD41 cells. -

Enhancing Skin Health: by Oral Administration of Natural Compounds and Minerals with Implications to the Dermal Microbiome

Review Enhancing Skin Health: By Oral Administration of Natural Compounds and Minerals with Implications to the Dermal Microbiome David L. Vollmer 1, Virginia A. West 1 and Edwin D. Lephart 2,* 1 4Life Research, Scientific Research Division, Sandy, Utah 84070, USA; [email protected] (D.L.V.); [email protected] (V.A.W) 2 Department of Physiology, Developmental Biology and The Neuroscience Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-801-422-2006 Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 1 October 2018; Published: 7 October 2018 Abstract: The history of cosmetics goes back to early Egyptian times for hygiene and health benefits while the history of topical applications that provide a medicinal treatment to combat dermal aging is relatively new. For example, the term cosmeceutical was first coined by Albert Kligman in 1984 to describe topical products that afford both cosmetic and therapeutic benefits. However, beauty comes from the inside. Therefore, for some time scientists have considered how nutrition reflects healthy skin and the aging process. The more recent link between nutrition and skin aging began in earnest around the year 2000 with the demonstrated increase in peer-reviewed scientific journal reports on this topic that included biochemical and molecular mechanisms of action. Thus, the application of: (a) topical administration from outside into the skin and (b) inside by oral consumption of nutritionals to the outer skin layers is now common place and many journal reports exhibit significant improvement for both on a variety of dermal parameters. Therefore, this review covers, where applicable, the history, chemical structure, and sources such as biological and biomedical properties in the skin along with animal and clinical data on the oral applications of: (a) collagen, (b) ceramide, (c) β-carotene, (d) astaxanthin, (e) coenzyme Q10, (f) colostrum, (g) zinc, and (h) selenium in their mode of action or function in improving dermal health by various quantified endpoints. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ Compared with Stat3flox/Flox

Supplemental Table 2 Genes down-regulated (<0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ compared with Stat3flox/flox Probe ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Entrez gene ID 1460599_at Ermp1 endoplasmic reticulum metallopeptidase 1 226090 1460463_at H60c histocompatibility 60c 670558 1460431_at Gcnt1 glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 1, core 2 14537 1459979_x_at Zfp68 zinc finger protein 68 24135 1459747_at --- --- --- 1459608_at --- --- --- 1459168_at --- --- --- 1458718_at --- --- --- 1458618_at --- --- --- 1458466_at Ctsa cathepsin A 19025 1458345_s_at Colec11 collectin sub-family member 11 71693 1458046_at --- --- --- 1457769_at H60a histocompatibility 60a 15101 1457680_a_at Tmem69 transmembrane protein 69 230657 1457644_s_at Cxcl1 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 14825 1457639_at Atp6v1h ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit H 108664 1457260_at 5730409E04Rik RIKEN cDNA 5730409E04Rik gene 230757 1457070_at --- --- --- 1456893_at --- --- --- 1456823_at Gm70 predicted gene 70 210762 1456671_at Tbrg3 transforming growth factor beta regulated gene 3 21378 1456211_at Nlrp10 NLR family, pyrin domain containing 10 244202 1455881_at Ier5l immediate early response 5-like 72500 1455576_at Rinl Ras and Rab interactor-like 320435 1455304_at Unc13c unc-13 homolog C (C. elegans) 208898 1455241_at BC037703 cDNA sequence BC037703 242125 1454866_s_at Clic6 chloride intracellular channel 6 209195 1453906_at Med13l mediator complex subunit 13-like 76199 1453522_at 6530401N04Rik RIKEN cDNA 6530401N04 gene 328092 1453354_at Gm11602 predicted gene 11602 100380944 1453234_at -

Occurrence of Sulfatide As a Major Glycosphingolipid in WHHL Rabbit Serum Lipoproteins1

J. Biochem. 102, 83-92 (1987) Occurrence of Sulfatide as a Major Glycosphingolipid in WHHL Rabbit Serum Lipoproteins1 Atsushi HARA and Tamotsu TAKETOMI Department of Lipid Biochemistry, Institute of Cardiovascular Disease , Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto , Nagano 390 Received for publication, February 12, 1987 Glycosphingolipids in serum and lipoproteins from Watanabe hereditable hyper li pidemic rabbit (WHHL rabbit), which is an animal model for human familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), were analyzed for the first time in this study . Chylo microns and very low density, low density, and high density lipoproteins contained sulfatide as a major glycosphingolipid (12nmol/ƒÊmol total phospholipids (PL) in chylomicrons, 19nmol/ƒÊmol PL in VLDL, 18nmol/ƒÊmol PL in LDL, and 14nmol/ƒÊ mol PL in HDL) with other minor glycosphingolipids such as glucosylceramide, galactosylceramide, GM3 ganglioside, lactosylceramide, and globotriaosylceramide. The concentration of sulfatide as a major glycosphingolipid in WHHL rabbit serum (121nmol/ml) was much higher than that in normal rabbit serum (3nmol/ml). Fatty acids of the sulfatides comprised mainly nonhydroxy fatty acids (C22, 23, and 24) and significant amounts of hydroxy fatty acids (about 10%), whereas long chain bases of the sulfatides comprised mostly (4E)-sphingenine with a significant amount of 4D-hydroxysphinganine (about 10%). Furthermore, sulfatides in the liver and small intestine from normal and WHHL rabbits (where serum lipoproteins are produced) were determined to amount to 260nmol/g liver in WHHL rabbit, 104 nmol/g liver in control rabbit, 99.6nmol/g small intestine in WHHL rabbit, and 31.2nmol/g small intestine in control rabbit. Ceramide portions of the sulfatides in the liver were mainly composed of (4E)-sphingenine and nonhydroxy fatty acids, while those in the small intestine were mainly composed of 4D-hydroxysphinganine and hydroxy fatty acids. -

Ceramide and Related Molecules in Viral Infections

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Ceramide and Related Molecules in Viral Infections Nadine Beckmann * and Katrin Anne Becker Department of Molecular Biology, University of Duisburg-Essen, 45141 Essen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-201-723-1981 Abstract: Ceramide is a lipid messenger at the heart of sphingolipid metabolism. In concert with its metabolizing enzymes, particularly sphingomyelinases, it has key roles in regulating the physical properties of biological membranes, including the formation of membrane microdomains. Thus, ceramide and its related molecules have been attributed significant roles in nearly all steps of the viral life cycle: they may serve directly as receptors or co-receptors for viral entry, form microdomains that cluster entry receptors and/or enable them to adopt the required conformation or regulate their cell surface expression. Sphingolipids can regulate all forms of viral uptake, often through sphingomyelinase activation, and mediate endosomal escape and intracellular trafficking. Ceramide can be key for the formation of viral replication sites. Sphingomyelinases often mediate the release of new virions from infected cells. Moreover, sphingolipids can contribute to viral-induced apoptosis and morbidity in viral diseases, as well as virus immune evasion. Alpha-galactosylceramide, in particular, also plays a significant role in immune modulation in response to viral infections. This review will discuss the roles of ceramide and its related molecules in the different steps of the viral life cycle. We will also discuss how novel strategies could exploit these for therapeutic benefit. Keywords: ceramide; acid sphingomyelinase; sphingolipids; lipid-rafts; α-galactosylceramide; viral Citation: Beckmann, N.; Becker, K.A. -

CDH12 Cadherin 12, Type 2 N-Cadherin 2 RPL5 Ribosomal

5 6 6 5 . 4 2 1 1 1 2 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R B , B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B , 9 , , , , 4 , , 3 0 , , , , , , , , 6 2 , , 5 , 0 8 6 4 , 7 5 7 0 2 8 9 1 3 3 3 1 1 7 5 0 4 1 4 0 7 1 0 2 0 6 7 8 0 2 5 7 8 0 3 8 5 4 9 0 1 0 8 8 3 5 6 7 4 7 9 5 2 1 1 8 2 2 1 7 9 6 2 1 7 1 1 0 4 5 3 5 8 9 1 0 0 4 2 5 0 8 1 4 1 6 9 0 0 6 3 6 9 1 0 9 0 3 8 1 3 5 6 3 6 0 4 2 6 1 0 1 2 1 9 9 7 9 5 7 1 5 8 9 8 8 2 1 9 9 1 1 1 9 6 9 8 9 7 8 4 5 8 8 6 4 8 1 1 2 8 6 2 7 9 8 3 5 4 3 2 1 7 9 5 3 1 3 2 1 2 9 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 5 9 5 3 2 6 3 4 1 3 1 1 4 1 4 1 7 1 3 4 3 2 7 6 4 2 7 2 1 2 1 5 1 6 3 5 6 1 3 6 4 7 1 6 5 1 1 4 1 6 1 7 6 4 7 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m -

A Review on the Potential Role of Vitamin D and Mineral Metabolism on Chronic Fatigue Illnesses Anna Dorothea Höck*

Höck et al. J Clin Nephrol Ren Care 2016, 2:008 Volume 2 | Issue 1 Journal of Clinical Nephrology and Renal Care Review Article: Open Access A Review on the Potential Role of Vitamin D and Mineral Metabolism on Chronic Fatigue Illnesses Anna Dorothea Höck* Internal Medicine, 50935 Cologne, Germany *Corresponding author: Anna Dorothea Hoeck, MD, Internal Medicine, Mariawaldstraße 7, 50935 Köln, Germany, E-Mail: [email protected] by any kind of cell stress as long as sufficient 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 Abstract (25OHD3) is available [8-11]. The aim of this report is to review the effects of vitamin D-deficiency on chronic mineral deregulation and its clinical consequences. 1,25(OH)2D3 induces in addition the gene expression of Recent research data are presented including the effects of vitamin following important mineral regulators such as calcium-sensing- D3-induced calcium sensing receptor (CaSR), fibroblast growth receptor (CaSR), Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 (FGF23) and its factor 23 (FGF23), the cofactor of FGF1-receptor α-klotho (αKl) co-receptor α-Klotho (αKL, also FGF23/αKL in this paper), yet and the interplay with each other and with vitamin D3-repressed represses the gene expression of parathormone (PTH) [2,6,12-16]. parathormone (PTH). The importance of persistent calcium- and phosphate deregulation following long-standing vitamin These mineral regulators, like 1,25(OH)2D3 itself, act not only via D3-deficiency for cellular functions and resistance to vitamin gene expression, but also modulate cell functions directly by rapid D3 treatment is discussed. It is proposed that chronic fatiguing non-genomic actions.