MCF 2017 Impact Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Guides Birding Tours Southwestern Ecuador

Field Guides Tour Report SOUTHWESTERN ECUADOR SPECIALTIES: JOCOTOCO FOUNDATION Mar 17, 2012 to Mar 31, 2012 Mitch Lysinger A common hummingbird of Ecuador's southwest, the Amazilia Hummingbird comes in two forms here: this lowland form, and a whiter-bellied highland form sometimes split off as Loja Hummingbird, A. alticola. (Photo by tour participant Brian Stech) This was yet another SW Ecuador trip packed full of spectacular highlights and surprises, the biggest bird surprise being the Buff-browed Foliage-gleaner that we found on the lower slopes of the Tapichalaca reserve, way out of its known range. This is a bird that had previously only been known in Ecuador from a record or two right along the Peruvian border! Many folks sign up for this tour for the chance at seeing the superb Jocotoco Antpitta; believe it or not "Superb Antpitta" was actually one of the name candidates! We indeed had superb views of this beast; seeing it is now not at all the chore it once was. Now? Hike in along the trail, have a seat on the bench, and they come running in to gobble down some jumbo-sized worms. What a show! Before this you had to pray that one would answer in the hopes of even just getting a quick glimpse. The weather surprises weren't quite as pleasant, causing huge numbers of landslides in the deep SW that prevented us from visiting a few key spots, such as the highland Tumbesian areas around Utuana reserve. The rains came about a month early this year, and they were particularly intense; in hindsight I actually count ourselves lucky because if we had run the trip about a week or two earlier, the road conditions would probably have made passage throughout SW Ecuador a complete nightmare! The countless landslides that we drove by were a testament to this. -

Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks

Mass Audubon’s Natural History Travel and Joppa Flats Education Center Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks, Thank you for participating in our amazing adventure to the wilds of Southern Ecuador. The vistas were amazing, the lodges were varied and delightful, the roads were interesting— thank goodness for Jaime, and the birds were fabulous. With the help of our superb guide Jose Illanes, the group managed to amass a total of 539 species of birds (plus 3 additional subspecies). Everyone helped in finding birds. You all were a delight to travel with, of course, helpful to the leaders and to each other. This was a real team effort. You folks are great. I have included your top birds, memorable experiences, location summaries, and the triplist in this document. I hope it brings back pleasant memories. Hope to see you all soon. Dave David M. Larson, Ph.D. Science and Education Coordinator Mass Audubon’s Joppa Flats Education Center Newburyport, MA 01950 Top Birds: 1. Jocotoco Antpitta 2-3. Solitary Eagle and Orange-throated Tanager (tied) 4-7. Horned Screamer, Long-wattled Umbrellabird, Rainbow Starfrontlet, Torrent Duck (tied) 8-15. Striped Owl, Band-winged Nightjar, Little Sunangel, Lanceolated Monklet, Paradise Tanager, Fasciated Wren, Tawny Antpitta, Giant Conebill (tied) Honorable mention to a host of other birds, bird groups, and etc. Memorable Experiences: 1. Watching the diving display and hearing the vocalizations of Purple-collared Woodstars and all of the antics, colors, and sounds of hummers. 2. Learning and recognizing so many vocalizations. 3. Experiencing the richness of deep and varied colors and abundance of birds. -

Tahiti to Easter Island Bird List -- September 29 - October 17, 2014 Produced by Peter Harrison & Jonathan Rossouw

Tahiti to Easter Island Bird List -- September 29 - October 17, 2014 Produced by Peter Harrison & Jonathan Rossouw BIRDS Date of sighting in September & October 2014 - Key for Locations on Page 4 Common Name Scientific Name 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Tinamous Chilean Tinamou Nothoprocta pedricaria X Petrels & Shearwaters Pseudobulweria Tahiti Petrel X X X X rostrata Murphy's Petrel Pterodroma ultima X X X X X X Juan Fernandez Petrel Pterodroma externa X X Kermadec Petrel Pterodroma neglecta X Herald Petrel Pterodroma heraldica X X Henderson Petrel Pterodroma atrata X X Phoenix Petrel Pterodroma alba X X Pterodroma nigripen- Black-winged Petrel X nis Gould's Petrel Pterodroma leucoptera X Cook's Petrel Pterodroma cookii X Pterodroma defilip- De Filippi's Petrel X piana Bulwer's Petrel Bulweria bulwerii X X X X X Wedge-tailed Shearwater Puffinus pacificus X X X X Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus X X X X Short-tailed Shearwater Puffinus tenuirostris X X Christmas Shearwater Puffinus nativitatis X Tropical Shearwater Puffinus bailloni X X X X X Storm Petrels Polynesian Storm-Petrel Nesofregetta fuliginosa X Tropicbirds Red-tailed Tropicbird Phaethon rubricauda X X X X X X X X White-tailed Tropicbird Phaethon lepturus X X X X X X X Boobies & Gannets Masked Booby Sula dactylatra X X X X X X X X Common Name Scientific Name 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Red-footed Booby Sula sula X X X X X X X X X X X X X Brown Booby Sula leucogaster X X X X X X X X X Frigatebirds Great Frigatebird Fregata minor X X X X X X X X X X -

Restoration of Vahanga Atoll, Acteon Group, Tuamotu Archipelago

ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION OF VAHANGA ATOLL, ACTEON GROUP, TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO OPERATIONAL PLAN 15 september 2006 Prepared by Ray Pierce1, Souad Boudjelas2, Keith Broome3, Andy Cox3, Chris Denny2, Anne Gouni4 & Philippe Raust4 1. Director, Eco Oceania Ltd. Mt Tiger Rd, RD 1 Onerahi, Northland, New Zealand. Ph #64 9 4375711. Email: [email protected] 2. Project Manager (PII), University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, SGES, Tamaki Campus, New Zealand. Ph: #64 9 3737599 xtn86822. Email: [email protected] 3. Island Eradication Advisory Group, Department of Conservation, Hamilton, New Zealand. Email [email protected] [email protected] 4. Société d'Ornithologie de Polynesie MANU. BP 21098, 98713 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie Française. Email: [email protected] Société d'Ornithologie de Polynésie "MANU" – B.P. 21098 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie française 1 Numéro TAHITI : 236778 - Email : [email protected] - Site internet : www.manu.pf - Tél. : 50 62 09 Operational Summary The following table summarises details of the proposed Rattus exulans eradication on Vahanga Island, French Polynesia. Location Vahanga Atoll: 382 ha (includes vegetated and unvegetated area) in the Acteon Group in the Tuamotu Archipelago, French Polynesia Primary target pest species Pacific rats (Rattus exulans) Secondary target species The invasive plant lantana (Lantana camara) – research, monitoring, determine feasibility for eradication Timing June-August 2007 (eradication of rats) Target benefit species Polynesian ground dove (Gallicolumba erythroptera) CR; Tuamotu sandpiper (Prosobonia cancellata) EN; atoll fruit dove (Ptilinopus coralensis); Murphy’s petrel (Pterodroma ultima); Bristle thighed curlew (Numenius tahitiensis) VU; potentially Phoenix petrel (Pterodroma alba) EN. Vegetation type Broadleaf forest, coconut plantation Climate characteristics Winter-spring dry season Community interests Uninhabited; Catholic church, coconut plantation Historic sites None known Project Coordinator Dr. -

Reserva YANACOCHA

Panorama of Cerro Tapichalaca from the western edge of the reserve FUNDACIÓN DE CONSERVACIÓ N JOCOTOCO 14 años protegiendo aves en peligro. En noviembre de 1997, una nueva especie de Antpitta fue descubierta en el extremo sur del Ecuador por Robert Ridgely, que posteriormente la denominaron Jocotoco Antpitta, Grallaria ridgelyi. Este evento se convirtió en un factor clave para la formación de Fundación Jocotoco. El Cerro Tapichalaca (a la izquierda), entre los Andes, es el sitio del descubrimiento del Jocotoco Antpitta. FUNDACIÓN DE CONSERVACIÓN JOCOTOCO Es una organización de conservación ecuatoriana, dedicada a la creación de reservas ecológicas a través de la adquisición de tierras privadas para proteger especies de aves globalmente amenazadas. Hasta el 2014 once reservas han alcanzado una extensión de alrededor de 20,000 hectáreas que proveen hábitat para cerca de 800 especies de aves. De estas alrededor de 90 son endémicas, y cerca de 40 son consideradas globalmente amenazadas. Entre estas, 74 son Migratorias Boreales. www.fjocotoco.org Fundación Jocotoco 2014 Once reservas: - cuatro en el Norte -cinco en el Sur - dos en el Oeste El socio de Jocotoco en el Reino Unido es World Land Trust Los socios de Fundación Jocotoco en los EEUU son: American Bird Conservancy y RFT En 1998, después de unos veinte años de investigación, se completó el trascendental trabajo “The Birds of Ecuador” de Robert Ridgely y Paul Greenfield, que describe e ilustra plenamente las 1600 especies conocidas que se encuentran en el Ecuador. La obra fue publicada a mediados de 2001. La edición en español fue preparada y publicada en Ecuador por la Fundación Jocotoco en 2007. -

Te Manu N°11

Te Manu N° 19 - Juin 1997 Bulletin de la Société d’Ornithologie de Polynésie MANU B.P. 21 098 Papeete Editorial Pour ce numéro une très large moisson d’observations de tous horizons : c’est le signe que nous avons été plus présents sur le terrain, mais notons que beaucoup d’entre elles viennent de visiteurs qui parfois se déplacent de fort loin pour avoir la chance de découvrir de si rares espèces. Alors nous qui vivons dans ces îles, sachons en profiter et faire connaître cette richesse à la population qui en à parfois oublié jusqu’au nom. C’est aussi pourquoi notre action dans les écoles ne manque pas d’intérêt, et celui ci nous est largement rendu par les enfants qui font souvent preuve de bien plus de curiosité que leurs parents. P. Raust L’ASSEMBLEE GENERALE DE LA SOCIETE D’ORNITHOLOGIE DE POLYNESIE « MANU » S’EST TENUE LE 7 JUIN 1997 AU LOCAL DE LA FAPE, 10 RUE JEAN GILBERT, QUARTIER DU COMMERCE A 10 HEURE . COMPTE RENDU DANS UN PROCHAIN « TE MANU ». SUR VOS AGENDAS AU SOMMAIRE • Observations Ornithologiques Les réunions du bureau se • Visites d’ornithologues tiennent tous les premiers • La S.O.P. en chiffres vendredi de chaque mois à partir • A la recherche du Rupe perdu de 16h30 au local de la FAPE, • MANU dans les écoles 10 rue Jean Gilbert, dans le quartier du commerce à Papeete • Revues & Articles, En Bref... : • Oiseaux mythiques de Hawaii • La nouvelle scientifique • Vendredi 4 juillet 1997 • Août : relâche • Et l’Oiseau sur la Branche Pomarea whitneyi • Vendredi 5 septembre 1997 OBSERVATIONS ORNITHOLOGIQUES • Jean-Pierre LUCE, notre correspondant-naturaliste des îles Marquises nous écrit - dans un style imagé et poétique qui lui est propre!- qu'il a observé lors d'un passage à Fatu Iva le Omokeke, monarque endémique de l'île (Pomarea whitneyi), "incroyablement peu farouche voir curieux de ce grand épouvantail en ciré" et nous confirme la présence à Omoa du Pihiti (Vini ultramarina), "la si touchante perruche bleue, hélas trop furtivement admirée".. -

TAHITI to EASTER ISLAND Marquesas, Tuamotus & Pitcairns Aboard the Island Sky October 10–29, 2019

TAHITI TO EASTER ISLAND Marquesas, Tuamotus & Pitcairns Aboard the Island Sky October 10–29, 2019 The Beautiful Bay at Fatu Hiva in the Marquesas © Brian Gibbons LEADER: BRIAN GIBBONS LIST COMPILED BY: BRIAN GIBBONS VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Crystalline waters, soaring volcanic peaks, windswept atolls blanketed in coconut palms, gorgeous corals and swarms of reef fishes, amazing seabirds, and a variety of rare endemic landbirds is the short summary of what we witnessed as we sailed across the South Pacific. We sampled the Society, Marquesas, and Tuamotu islands in French Polynesia and three of the four Pitcairns before we ended in the legendary realm of giant Moai on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Tawhiri (Polynesian god of wind and storms) was good to us, as we had fine weather for most of our shore excursions and smooth sailing for nearly the entire 3,700 miles of Pacific we crossed in making our way from Tahiti to Easter Island. Our first spectacular Polynesian Sunset as seen from Tahiti at the Intercontinental Resort © Brian Gibbons Before we even boarded the Island Sky, we sought some great birds in Papehue Valley where Tahiti Monarchs, critically endangered, have a population around eighty birds, up from a low of 12 in 1998. In the parking lot, the Society Kingfishers chattered and sat up for scope views, then Gray-green Fruit-Doves floated past, and just like that we had witnessed two endemics. We started hiking up the trail, into the verdant forest and crossing the stream as we climbed into the narrow canyon. -

Current Status of the Endangered Tuamotu Sandpiper Or Titi Prosobonia Cancellata and Recommended Actions for Its Recovery

Current status of the endangered Tuamotu Sandpiper or Titi Prosobonia cancellata and recommended actions for its recovery R.J. PIERCE • & C. BLANVILLAIN 2 WildlandConsultants, PO Box 1305, Whangarei,New Zealand. raypierce@xtra. co. nz 2Soci•t• d'Omithologiede Polyn•sieFrancaise, BP 21098, Papeete,Tahiti Pierce,R.J. & Blanvillain, C. 2004. Current statusof the endangeredTuamotu Sandpiper or Titi Prosobonia cancellataand recommendedactions for its recovery.Wader StudyGroup Bull. 105: 93-100. The TuamotuSandpiper or Titi is the only survivingmember of the Tribe Prosoboniiniand is confinedto easternPolynesia. Formerly distributedthroughout the Tuamotu Archipelago,it has been decimatedby mammalianpredators which now occuron nearlyall atollsof the archipelago.Isolated sandpiper populations are currentlyknown from only four uninhabitedatolls in the Tuamotu.Only two of theseare currentlyfree of mammalianpredators, such as cats and rats, and the risks of rat invasionon themare high. This paper outlines tasksnecessary in the shortterm (within five years)to securethe species,together with longerterm actions neededfor its recovery.Short-term actions include increasing the securityof existingpopulations, surveying for otherpotential populations, eradicating mammalian predators on key atolls,monitoring key populations, and preparing a recovery plan for the species. Longer term actions necessaryfor recovery include reintroductions,advocacy and research programmes. INTRODUCTION ecologyof the TuamotuSandpiper as completelyas is cur- rently known, assessesthe -

Southern Ecuador: Birding & Nature | Trip Report November 28 – December 11, 2018 | Written by Bob Behrstock

Southern Ecuador: Birding & Nature | Trip Report November 28 – December 11, 2018 | Written by Bob Behrstock With Local Guide Andrea Molina, Bob Behrstock, and participants Dick, Diane, Irene, Trudy, Mike, Rita, Ann, Karen, Kathy, and Phil. Naturalist Journeys, LLC / Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 / 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com / caligo.com [email protected] / [email protected] Wed., Nov. 28 Arrival in Quito | Birding at Puembo Birding Garden Most participants arrived one to several days early, taking advantage of sightseeing in and around Quito, or a bit of extra birding. Those who’d been in Quito transferred to Puembo during this afternoon. Mike and Rita arrived in Ecuador during the day and Ann came in very late at night--or was it very early the next morning? Phil, Bob, and Karen, who’d all arrived a couple days early and been at Puembo, went afield with a local guide, visiting the Papallacta Pass area and Guango Lodge east of Quito. Birding around Puembo provided arriving participants with some high elevation garden birds, including Sparkling Violetear, Western Emerald, Black-tailed Trainbearer, Vermilion Flycatcher, Golden Grosbeak, Scrub and Blue-and-yellow tanagers, Saffron Finch, Shiny Cowbird, the first of many Great Thrushes, and Rufous-collared Sparrows. Bob was happy to reunite with his old friend Mercedes Rivadeniera, our ground agent and gracious owner of Puembo Birding Garden, whom he’d known since they met in eastern Ecuador during the 1980’s. Thur., Nov. 29 Early departure | Flight to Guayaquil | Birding our way to Umbrellabird Lodge (Buenaventura) An early flight to Guayaquil necessitated an early breakfast and airport transfer. -

N° English Name Latin Name Status Day 1 Day 2

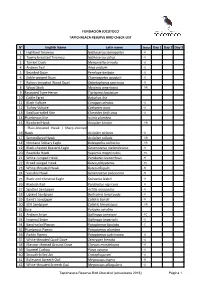

FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO TAPICHALACA RESERVE BIRD CHECK-LIST N° English Name Latin name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei - R 2 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius - U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata - U 4 Andean Teal Anas andium - U 5 Bearded Guan Penelope barbata - U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii - U 7 Rufous-breasted Wood Quail Odontophorus speciosus - R 8 Wood Stork Mycteria americana - VR 9 Fasciated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma fasciatum 10 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 11 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus - U 12 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura - U 13 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus - U 14 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 15 Bicolored Hawk Accipiter bicolor - VR Plain-breasted Hawk / Sharp-shinned 16 Hawk Accipiter striatus - U 17 Semicollared Hawk Accipiter collaris - VR 18 Montane Solitary Eagle Buteogallus solitarius - VR 19 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus - R 20 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris - FC 21 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous - R 22 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus - FC 23 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula - R 24 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma - R 25 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori - R 26 Blackish Rail Pardirallus nigricans - R 27 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius - R 28 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda - R 29 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii - R 30 Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus - VR 31 Sora Porzana carolina 32 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni - FC 33 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis - U 34 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas -

Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (Custom Tour)

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador 18th November – 6th December 2019 Hummingbirds were a big feature of this tour; with 58 hummingbird species seen, that included some very rare, restricted range species, like this Blue-throated Hillstar. This critically-endangered species was only described in 2018, following its discovery a year before that, and is currently estimated to number only 150 individuals. This male was seen multiple times during an afternoon at this beautiful, high Andean location, and was widely voted by participants as one of the overall highlights of the tour (Sam Woods). Tour Leader: Sam Woods Photos: Thanks to participant Chris Sloan for the use of his photos in this report. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southern ECUADOR: Nov-Dec 2019 (custom tour) Southern Ecuador ranks as one of the most popular South American tours among professional bird guides (not a small claim on the so-called “Bird Continent”!); the reasons are simple, and were all experienced firsthand on this tour… Ecuador is one of the top four countries for bird species in the World; thus high species lists on any tour in the country are a given, this is especially true of the south of Ecuador. To illustrate this, we managed to record just over 600 bird species on this trip (601) of less than three weeks, including over 80 specialties. This private group had a wide variety of travel experience among them; some had not been to South America at all, and ended up with hundreds of new birds, others had covered northern Ecuador before, but still walked away with 120 lifebirds, and others who’d covered both northern Ecuador and northern Peru, (directly either side of the region covered on this tour), still had nearly 90 new birds, making this a profitable tour for both “veterans” and “South American Virgins” alike. -

South Ecuador January/February 2020

South Ecuador January/February 2020 SOUTH ECUADOR A report on birds seen on a trip to South Ecuador From 22 January to 16 February 2020 Jocotoco Antpitta Grallaria ridgelyi By Henk Hendriks Hemme Batjes Wiel Poelmans Peter de Rouw 1 South Ecuador January/February 2020 INTRODUCTION This was my fourth trip to Ecuador and this time I mainly focussed on the southern part of this country. The main objective was to try to see most of the endemics, near-endemics and specialties of the southern part of Ecuador. In 2010 my brother and I had a local bird guide for one day to escort us around San Isidro and we had a very enjoyable day with him. His name was Marcelo Quipo. When browsing through some trip reports on Cloudbirders I came upon his name again when he did a bird tour in the south with some birders, which were very pleased with his services. So I contacted Marcelo and together we developed a rough itinerary for a 22-day trip. The deal was that we would pay for transport and his guiding fees and during the trip we would take care of all the expenses for food and accommodation. Marcelo did not make any reservations regarding accommodations and this was never really a problem and gave us a lot of flexibility in our itinerary. We made several alterations during the trip. Most birders start and end their trip in Guayaquil but we decided to start in Cuenca and end in Guayaquil. The advantage of this was that we had a direct flight with KLM from Amsterdam to Quito and a direct flight from Guayaquil back to Amsterdam.