The Art of Julian Cooper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Summits Lakeland

OUR PLANET OUR PLANET LAKELAND THE MARKS SUMMITS OF A GLACIER PHOTO Glacially scoured scenery on ridge between Grey Knotts and Brandreth. The mountain scenery Many hillwalkers and mountaineers are familiar The glacial scenery is a product of all these aries between the different lava flows, as well as the ridge east of Blea Rigg. However, if you PHOTO LEFT Solidi!ed lava "ows visible of Britain was carved with key features of glacial erosion such as deep phases occurring repeatedly and affecting the as the natural weaknesses within each lava flow, do have a copy of the BGS geology map, close across the ridge on High Rigg. out by glaciation in the U-shaped valleys, corries and the sharp arêtes that whole area, including the summits and high ridges. to create the hummocky landscape. Seen from the attention to what it reveals about the change from PHOTO RIGHT Peri glacial boulder!eld on often separate adjacent corries (and which provide Glacial ‘scouring’ by ice sheets and large glaciers summit of Great Rigg it is possible to discern the one rock formation to another as you trek along the summit plateau of Scafell Pike. not very distant past. some of the best scrambles in the Lakeland fells, are responsible for a typical Lakeland landscape pattern of lava flows running across the ridgeline. the ridge can help explain some of the larger Paul Gannon looks such as Striding Edge and Sharp Edge). of bumpy summit plateaus and blunt ridges. This Similar landscapes can be found throughout the features and height changes. -

Wainwright's Central Fells

Achille Ratti Long Walk - 22nd April 2017 – Wainwright’s Central Fells in a day by Natasha Fellowes and Chris Lloyd I know a lot of fell runners who are happy to get up at silly o'clock to go for a day out. I love a day out but I don't love the early get ups, so when Dave Makin told me it would be a 4am start this time for the annual Achille Ratti Long Walk, the idea took a bit of getting used to. The route he had planned was the Wainwright's Central Fells. There are 27 of them and he had estimated the distance at 40 ish miles, which also took some getting used to. A medium Long Walk and a short Long Walk had also been planned but I was keen to get the miles into my legs. So after an early night, a short sleep and a quick breakfast we set off prompt at 4am in cool dry conditions from Bishop’s Scale, our club hut in Langdale. Our first top, Loughrigg, involved a bit of a walk along the road but it passed quickly enough and we were on the top in just under an hour. The familiar tops of Silver Howe and Blea Rigg then came and went as the sun rose on the ridge that is our club's back garden. I wondered whether anyone else at the hut had got up yet. The morning then started to be more fun as we turned right and into new territory for me. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

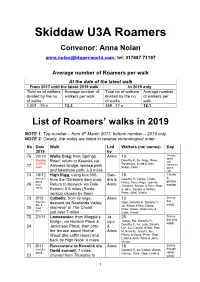

List of Roamers' Walks

Skiddaw U3A Roamers Convenor: Anna Nolan [email protected]; tel: 017687 71197 Average number of Roamers per walk At the date of the latest walk From 2017 until the latest 2019 walk In 2019 only Total no of walkers Average number of Total no of walkers Average number divided by the no walkers per walk divided by the no of walkers per of walks of walks walk 1,001 : 75 = 13.3 489 : 27 = 18.1 List of Roamers’ walks in 2019 NOTE 1: Top number – from 9th March 2017; bottom number – 2019 only NOTE 2: Clearly, the walks are listed in reverse chronological order No Date Walk Led Walkers (no/ names) Day 2019 by 75 22/12 Walla Crag; from Springs Anna 10 Clouds, some Sunday Road; return to Keswick via Dorothy H, Jo, Angy, Rose, sun, 27 EXTRA Ashness Bridge, terrace path Rosemary, Linda & Alan, rainbows, walk Robin, Peter some and lakeshore path; 6.5 miles rain 74 18/12 High Rigg; using bus 555; San- 18 Cloudy & Resche- from the Thirlmere dam road, dra & Dorothy H, Carole, Linda, duled Hilary, Pam, Angy, Joanna, getting 26 from Return to Keswick via Dale Anna Christine, Miriam & Pete, Rose windier 19/12 Bottom; 6.5 miles (9-mile & John, Sandra & Alistair, version chosen by thee) Peter, Stan, Vinnie 73 9/12 Catbells; from Grange; Anna 13 Sunny but Resche- descent via Newlands Valley; Olga, Dorothy H, Dorothy C, duled Jo, Alison, Hilary, David, windy 25 from stop-over at The Chalet; Peter, Robin, Rosemary & 5/12 just over 7 miles Colin, Vinnie 72 21/11 Loweswater; from Maggie’s Ja- 25 Sunny but very Bridge; via Hudson Place & cqui Jacqui, Pat, -

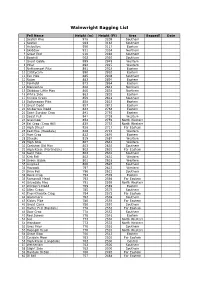

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far -

Kendal Mountaineering Club

KMC Meets List 2013/14 v2 Date Meet type Venue and description Organiser Meeting Point 1-3 Feb Weekend Scotland Winter meet - Milehouse Cottage, Aviemore (12 places) Conan Harrod Fully Booked [email protected] 22-24 Feb Weekend Scotland Winter meet – CIC Hut, Ben Nevis (8 places) Conan Harrod Fully Booked [email protected] 6 April Saturday Shepherds Crag - Introductory Day (NY 263 185) Plumgarths Our introductory day provides an opportunity for members new and old to get together. It is particularly 9:00am useful for new members to get to know others. Shepherd’s is an ideal venue, with high quality, friendly climbs in a sheltered location. 9 April Evening Hutton Roof (SD 566 783) Crooklands An ideal place to make the transition from indoors to out, with short routes and lots of bouldering. Hope we Ian Harrison get a big turn out to start the season off well. [email protected] Pub: Kings Arms, Burton in Kendal 16 April Evening Farleton Crag/ Newbiggin (Routes or bouldering) (SD 539 797) Crooklands Another early season favourite. Choose between routes (and some bouldering) at Farleton or bouldering at Newbiggin on the other side of the fell. Restricted parking, car sharing essential Pub: Smithy Inn, Holme 23 April Evening Twistleton Scars (SD 716 762) Crooklands This popular Limestone crag has a great outlook overlooking Ingleborough. With a huge choice of short John Hollingworth routes on offer, an evenings visit will give you just a taster of what’s on offer. You have to pay to park at the [email protected] farm so car sharing advisable Pub: Marton Arms, Thornton in Lonsdale 30 April Evening Castle Rock, Thirlmere / Carrock Fell (routes or bouldering) (NY 321 196) / (NY 356 324) Plumgarths Choose between the steep routes of Castle Rock North Crag, the more amenable South Crag or for something completely different, bouldering on the Gabbro of Carrock Fell. -

Northern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday – the Central Fells

Northern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday – The Central Fells Tour Style: Challenge Walks Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: DBWBH Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Wainwright's third fell guide covers the high ground bordered by Borrowdale, Thirlmere, Grasmere, Rydal and Langdale, and includes hills ranging from the iconic mountain classics of the Langdale Pikes to little-explored ridges above Watendlath. In this week, not only do we climb all 27 of Wainwright's named Central Fells, we also explore routes between these well-loved valleys that would be impracticable if travelling by car. The Central Fells feature 8 mountains that are over 2000ft, so a good head for heights is a must on this challenging holiday! HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow in the footsteps of Alfred Wainwright exploring some of his favourite fells • Bag all of the summits in his Central Pictorial Guide • Enjoy challenging walking with wonderful views and a great sense of achievement • Admire panoramic mountain, lake and river views from fells and peaks • Let an experienced walking leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Enjoy magnificent Lake District scenery • Stay in a beautiful country house where you can relax and share stories of your day in the evenings TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded walking Activity Level 6. ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check-in to your room from 2:30 p.m. onwards (upgraded rooms from 1 p.m.) Please join us for afternoon tea and take some time to settle in at Derwent Bank and discuss the week’s programme. -

Wain No Name Wain Ht District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike

Wain no Name Wain ht District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike 3210 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell Pike from Scafell 2 Scafell 3162 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell 3 Helvellyn 3118 EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn summit 4 Skiddaw 3053 NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw 5 Great End 2984 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Great End 6 Bowfell 2960 SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell from Crinkle Crags 7 Great Gable 2949 WEST GABLE y map Great Gable from the Corridor Route 8 Pillar 2927 WEST PILLAR y map Pillar from Kirk Fell 9 Nethermost Pike 2920 EAST HELVELLYN y map Nethermost Pike summit 10 Catstycam 2917 EAST HELVELLYN y map Catstycam 11 Esk Pike 2903 SOUTH BOWFELL y map Esk Pike 12 Raise 2889 EAST HELVELLYN y map Raise from White Side 13 Fairfield 2863 EAST FAIRFIELD y map Fairfield from Gavel Pike 14 Blencathra 2847 NORTH BLENCATHRA y map Blencathra 15 Skiddaw Little Man 2837 NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw Little Man 16 White Side 2832 EAST HELVELLYN y map White Side summit 17 Crinkle Crags 2816 SOUTH CRINKLE CRAGS y map Crinkle Crags from Pike O' Blisco 18 Dollywaggon Pike 2810 EAST HELVELLYN y map Dollywaggon Pike 19 Great Dodd 2807 EAST DODDS y map Great Dodd 20 Grasmoor 2791 NORTH-WEST GRASMOOR y map Grasmoor 21 Stybarrow Dodd 2770 EAST DODDS y map Stybarrow Dodd across Sticks Pass 22 Scoat Fell 2760 WEST PILLAR y map Scoat Fell's summit 23 St Sunday Crag 2756 EAST FAIRFIELD y map St Sunday Crag from Birks 24 Crag Hill [Eel Crag] 2749 NORTH-WEST COLEDALE y map Crag Hill from Grasmoor 25 High Street 2718 FAR-EAST HIGH STREET y map High Street 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 2707 -

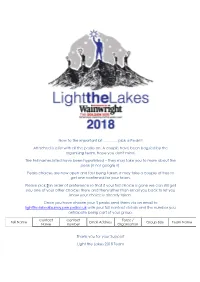

Light-The-Lakes-List-Of-Peaks-22 01 18

Now to the important bit………… pick a Peak!!! Attached is a list with all the peaks on. A couple have been bagsied by the organising team, hope you don't mind. The Fell names listed have been hyperlinked – they may take you to more about the peak (if not google it). Peaks choices are now open and fast being taken, it may take a couple of tries to get one confirmed for your team. Please pick 3 in order of preference so that if your first choice is gone we can still get you one of your other choices there and then rather than email you back to let you know your choice is already taken. Once you have chosen your 3 peaks send them via an email to [email protected] with your full contact details and the number you anticipate being part of your group. Contact Contact Force / Fell Name Email Address Group Size Team Name Name number Organisation Thank you for your Support Light the Lakes 2018 Team Height Height Fell Name GPS reference (m) (Ft) 12 Raise 883 2897 NY 34277 17414 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 NY 26679 27785 16 White Side 863 2832 NY 33780 16663 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 NY 34193 20556 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 NY 34295 18923 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 NY 36930 13404 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 NY 15940 11384 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 NY 19267 20364 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 NY 16530 10610 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 NY 36907 11208 31 Kirk Fell 802 2631 NY 19498 10485 32 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 NY 44826 13453 33 Swirl How 802 2631 NY 27282 00551 34 Green Gable 801 2628 NY 21472 10716 35 Lingmell 800 2625 -

Hts Walking the Wainwrights 64 Walks to Climb the 214 Wainwrights of Lakeland

Walking the Wainwrights Walking Walking the Wainwrights Walking the Wainwrights 64 WALKS TO CLIMB THE 214 WAINWRIGHTS OF LAKELAND 64 WALKS TO CLIMB THE 214 WAINWRIGHTS OF LAKELAND In this book you’ll find 64 routes that, if you complete them all, by default you will also have completed the Wainwrights. A few of the summits are featured in more than one walk. That’s ok. You can do them more than once! Why do we need a guide book on the fells of the Lake District if Wainwright wrote seven of them? Well, I should say right here that this book is not intended to replace Wainwright’s UneyGraham Pictorial Guides. They are superb books. But, they were written in the 1950s and 60s, and yes, some things in the hills have changed in the intervening years. Another reason is that many walkers struggle to devise full-day walks using the Wainwright guide books. Yes, he has detailed pretty much every conceivable way of getting to each individual summit, but this leaves the reader having to then come up with their own plan to make a longer day of it by continuing over one or more other fells. Wainwright didn’t describe day walks in these seven guidebooks. He described individual ways up and down each one. So, please buy the Wainwright guidebooks if you haven’t got them on your bookshelves already. Just 9 781906 095789 use them alongside this book. Cover – On Rannerdale Knotts with the bulk of Robinson behind (Walk 54). Back cover – The Buttermere Fells and Grasmoor seen from Haycock (Walk 63). -

Northern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday – the Central Fells

Northern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday – The Central Fells Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: DBWBH Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Wainwright's third fell guide covers the high ground bordered by Borrowdale, Thirlmere, Grasmere, Rydal and Langdale, and includes hills ranging from the iconic mountain classics of the Langdale Pikes to little-explored ridges above Watendlath. In this week, not only do we climb all 27 of Wainwright's named Central Fells, we also explore routes between these well-loved valleys that would be impracticable if travelling by car. The Central Fells feature 8 mountains that are over 2000ft, so a good head for heights is a must on this challenging holiday! WHAT'S INCLUDED • Great value: all prices include full board en-suite accommodation, a full programme of walks with all transport to and from the walks, and evening activities • Great walking: enjoy the challenge of bagging all of the summits in Wainwright’s Central Fells pictorial guide, accompanied by an experienced leader • Accommodation: enjoy a lakeside location just two miles from Keswick, with fantastic views of the www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 surrounding fells HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow in the footsteps of Alfred Wainwright exploring some of his favourite fells • Bag all of the summits in his Central Pictorial Guide • Enjoy challenging walking with wonderful views and a great sense of achievement • Admire panoramic mountain, lake and river views from fells and peaks • Let an experienced walking leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Enjoy magnificent Lake District scenery • Stay in a beautiful country house where you can relax and share stories of your day in the evenings ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check-in to your room from 2:30 p.m.