“Consider Yourself One of Us”: the Dickens Musical on Stage and Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Musical Theater Recital Assisted by Ms

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Joy Kenyon Senior Musical Theater Recital assisted by Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble Women’s Chorus, Scott Foreman, Daniel Bravo James Kenyon, & Jessica Ziegelbauer Monday, April 13, 2015 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert Please turn off all cell phones and electronics. PROGRAM Just Leave Everything To Me from Hello Dolly Jerry Herman • b. 1931 100 Easy Ways To Lose a Man from Wonderful Town Leonard Bernstein • 1918 - 1990 Betty Comden • 1917 - 2006 Adolph Green • 1914 - 2002 Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist The Man I Love from Lady, Be Good! George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Love is Here To Stay from The Goldwyn Follies Embraceable You from Girl Crazy Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist; Scott Foreman, Bass Guitar; Daniel Bravo, Percussion Steam Heat (Music from The Pajama Game) Choreography by Mrs. Kellis McSparrin Oldenburg Dancer: Joy Kenyon He Lives in You (reprise) from The Lion King Mark Mancina • b. 1957 Jay Rifkin & Lebo M. • b. 1964 arr. Dr. Owen Rockwell Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble; Maddi Jolley, Brooke Kressin, Grace Anna Randall, Mariah Taylor, Elizabeth Walczak, Rachel Walczak, Evangeline Wilds, Julie Wolfe & Jessica Ziegelbauer INTERMISSION The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 Sweet Liberty from Jane Eyre Paul Gordon • b. -

Guild Gmbh Switzerland GUILD MUSIC GLCD 5223 Contrasts, Volume 2

GUILD MUSIC GLCD 5223 Contrasts, Volume 2 2014 Guild GmbH GLCD 5223 © 2014 Guild GmbH Guild GmbH Switzerland GUILD MUSIC GLCD 5223 Contrasts, Volume 2 CONTRASTS: FROM THE 1960s BACK TO THE 1920s – Volume 2 GLCD 5179 Portrait of My Love GLCD 5199 Three Great American Light Orchestras GLCD 5180 Bright and Breezy GLCD 5200 A Glorious Century of Light Music 1 Gala Premiere (Laurie Johnson) 2:49 GLCD 5181 The Lost Transcriptions – Vol. 2 GLCD 5201 Fiddles and Bows GROUP-FIFTY ORCHESTRA Conducted by LAURIE JOHNSON – KPM 109 1962 GLCD 5182 A Second A-Z of Light Music GLCD 5202 Cinema Classics GLCD 5183 A Return Trip to the Library GLCD 5203 Great British Composers – Vol. 2 GLCD 5184 The Lost Transcriptions – Vol. 3 GLCD 5204 Salon, Light & Novelty Orchestras 2 La Dolce Vita (Nino Rota, arr. Brian Fahey) 2:48 GLCD 5185 Christmas Celebration GLCD 5205 Here’s To Holidays CYRIL ORNADEL AND THE STARLIGHT SYMPHONY – MGM SE 4033 1962 GLCD 5186 Light Music While You Work – Vol. 3 GLCD 5206 Non-Stop To Nowhere GLCD 5187 Light and Easy GLCD 5207 Ça C’est Paris 3 Travel Topic (Robert Farnon) 2:24 GLCD 5188 The Art of the Arranger – Vol. 1 GLCD 5208 The Lost Transcriptions – Vol. 4 GLCD 5189 Holidays for Strings GLCD 5209 My Dream is Yours QUEEN’S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA Conducted by ROBERT FARNON – Chappell C 738 1962 GLCD 5190 Continental Flavour – Vol. 2 GLCD 5210 Invitation to the Dance GLCD 5191 Strings Afire GLCD 5211 Light Music While You Work – Vol. 5 4 “Young At Heart” – Theme from the film (Johnny Richards; Carolyn Leigh) 3:07 GLCD 5192 Stereo into the Sixties GLCD 5212 Bright Lights RUSS CONWAY, piano, with TONY OSBORNE AND HIS ORCHESTRA and GLCD 5193 The Art of the Arranger – Vol. -

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Pocket Edition!

Matthew Brannon matthew brannon As the literary form of the new bourgeoisie, the biography is a sign of escape, or, to be more precise, of evasion. In order not to expose themselves through insights that question the very existence of the bourgeoisie, writers of biographies remain, as if up against a wall, at the threshold to which they have been pushed by world events. - SIGFRIED KRACAUER, The Biography as an Art Form of the New Bourgeoisie, 1930 in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, Oxford University Press, 2002 Call yourself an actor? You’re not even a bad actor. You can’t act at all, you fucking stupid hopeless sniveling little cunt-faced cunty fucking shit-faced arse-hole… - LAURENCE OLIVIER to Laurence Havery from Robert Stephen’s Knight Errant: Memoirs of a Vagabond Actor, Hodder and Stoughton, 1995 In show business, it’s folly to talk about what the future holds. Things change so fast. Today’s project so easily becomes tomorrow’s disappointment… The world of the film star is an obstacle race against time. The pitfalls and wrong turnings you can make are devastating. Often I fear for the sanity of some of my friends… The dice are loaded against you. There’s so much bitchery around, you really have to fight hard to survive. Everybody is against you… you have to fight for… success, sell your soul for it even. And when one finally achieved success, it was resented. Not by the great stars like Frank Sinatra, but by the little, frustrated people. They’re the ones to look out for, because brother, they’re gunning for you. -

Brooklyn College Program

Brooklyn College and Passport to Broadway Present the Premiere Musical Theatre Intensive Final Workshop Showcase Thursday June 25, 2015 – 2:00pm to 4:00pm - Roosevelt Hall Rehearsal Studios Students Adama Jackson – BFA Student Jacob Merwin – BA Student Adolfo "Fito" Alvarado – BFA Student Joseph Masi – MFA Student Alexandra Slater – BFA Student Katherine George – BA Student Carolyn Coppege – MFA Graduate Lisa Campbell – MFA Student Cassandra Borgella – BA Student Natalia Laspina – BA Graduate Chrissy Brinkman – MFA Student Rebecca Shumel – BA Student Conner James Sheridan – BFA Student Stefaniya Makarova – BA Graduate Director/Producer: Amy Weinstein is producer, director, published writer and Adjunct Professor of Acting. Amy is the President, CEO and Founder of StudentsLive, A Global Broadway Education Company for the past 14 years and more recently Artistic Director of Sister Company, Passport to Broadway International. Starting literally with just an idea, StudentsLive grew into one of the world’s most significant theater education programs with an annual budget of over 1 million dollars and annual international programs engaging groups from Brazil, South Korea, Italy, China, Guatemala and Japan. After 15 years of growth, it now boasts partnerships with virtually every single hit Broadway show, endorsements from America’s political, cultural, and artistic leaders, alliances with foreign governments and the highest standards of theater arts education on Broadway today. Most importantly, tens of thousands of young people across the globe have been transformed by StudentsLive programs. Choreographer/Assistant Director: Stephen Brotebeck recently served as the Movement Associate on the Tony Award winning Broadway production of Peter and the Starcatcher both on Broadway and at New World Stages. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

Spotlight on Learning Oliver

Spotlight on Learning a Pioneer Theatre Company Classroom Companion Pioneer Theatre Company’s Student Matinee Program is made possible through the support of Salt Lake Oliver County’s Zoo, Arts and Music, Lyrics and Book by Lionel Bart Parks Program, Salt Dec. 2 - 17, 2016 Lake City Arts Council/ Directed by Karen Azenberg Arts Learning Program, The Simmons “Bleak, dark, and piercing cold, it was a night for the well-housed and Family Foundation, The fed to draw round the bright fire, and thank God they were at home; Meldrum Foundation and for the homeless starving wretch to lay him down and die. Many Endowment Fund and hunger-worn outcasts close their eyes in our bare streets at such times, R. Harold Burton who, let their crimes have been what they may, can hardly open them in Foundation. a more bitter world.” “Please sir, I want some more.” – Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (1837) All these years after Charles Dickens wrote these words, there are still Spotlight on Learning is provided families without homes and children who are hungry. to students through a grant As this holiday season approaches, I am grateful for health, home, and family provided by the — but am also reminded by Oliver! to take a moment to remember those less George Q. Morris Foundation fortunate. I thank you for your support of Pioneer Theatre Company and wish you the merriest of holidays, and a happy and healthy New Year. Karen Azenberg Approx. running time: Artistic Director 2 hours and 15 minutes, including one fifteen-minute intermission. Note for Teachers: “Food, Glorious Food!” Student Talk-Back: Help win the fight against hunger by encouraging your students to bring There will be a Student Talk-Back a food donation (canned or boxed only) to your performance of Oliver! directly after the performance. -

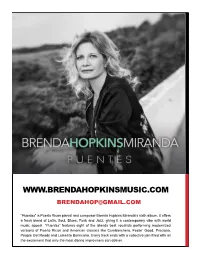

[email protected]

WWW.BRENDAHOPKINSMUSIC.COM [email protected] “Puentes” is Puerto Rican pianist and composer Brenda Hopkins Miranda’s sixth album. It offers a fresh blend of Latin, Soul, Blues, Funk and Jazz, giving it a contemporary vibe with world music appeal. “Puentes” features eight of the islands best vocalists performing modernized versions of Puerto Rican and American classics like Cumbanchero, Feelin’ Good, Preciosa, People Get Ready and Lamento Borincano. Every track ends with a collective jam filled with all the excitement that only the most daring improvisers can deliver. GUEST WWW.BRENDAHOPKINSMUSIC.COM [email protected] ARTISTS Fofé: voice (1) SONGS Jeanne d’Arc Casas: footwork and claps (2, 6) 1. Cumbanchero (Rafael Hernández) feat. Fofé SPANISH Cheryl Rivera: voice (3, 8) 2. Muéveme el Cafecito (Jesús Sánchez Erazo “Don Chuito”) feat. Emily Gómez: voice (4) Jeanne d’Arc Casas INSTRUMENTAL Lizbeth Román: voice, 3. Feelin’ Good (Anthony Newley & Leslie Bricusse) feat. Cheryl guitar (6) Rivera ENGLISH Javier Gómez: voice, harmónica (8), guitar (3) 4. Black Coffee (Sonny Burke & Paul Francis Webster) feat. Emily Ana del Rocío: voice (9) Gómez ENGLISH Eduardo Alegría: voice (10) 5. Preciosa (Rafael Hernández) INSTRUMENTAL Tito Auger: voice (11) 6. Verde Luz (Antonio Cabán Vale) feat. Lizbeth Román SPANISH 7. Lamento Borincano (Rafael Hernández) PIANO SOLO 8. Romance del Campesino (Roberto Cole) feat. Javier Gómez and MUSICIANS Cheryl Rivera SPANISH Brenda Hopkins Miranda: 9. People Get Ready (Curtis Mayfield) feat. Ana del Rocío piano, claps ENGLISH Manuel Martínez: drums 10. Sal a Caminar (Roy Brown) feat. Eduardo Alegría SPANISH David de León: bass 11. Donde Yo Nací (Claudio Ferrer) feat. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no.