Technologies for Meeting the UK's Emissions Reduction Targets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Commons Official Report

Monday Volume 650 26 November 2018 No. 212 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 26 November 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 26 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 26 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 September 2021 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions followed by Scottish Government Debate: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Current Msps by NHS Board

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 13 May 2021 Updated: 16:00 Current MSPs by NHS Board This Fact Sheet lists all current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who represent constituencies or regions within the boundaries of each of the NHS Boards in Scotland. The NHS Boards are listed in alphabetical order, followed by the name of the MSPs, their party and the constituency (C) or region (R) they represent. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Ayrshire and Arran Siobhian Brown (SNP) Ayr (C) Elena Whitham (SNP) Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley (C) Kenneth Gibson (SNP) Cunninghame North (C) Ruth Maguire (SNP) Cunninghame South (C) Willie Coffey (SNP) Kilmarnock and Irvine Valley (C) Current MSPs by NHS Board 1 Sharon Dowey (Con) South Scotland (R) Emma Harper (SNP) South Scotland (R) Craig Hoy (Con) South Scotland (R) Carol Mochan (Lab) South Scotland (R) Colin Smyth (Lab) South Scotland (R) Martin Whitfield (Lab) South Scotland (R) Brian Whittle (Con) South Scotland (R) Neil Bibby (Lab) West Scotland (R) Katy Clark (Lab) West Scotland (R) Russell Findlay (Con) West Scotland (R) Jamie Greene (Con) West Scotland (R) Ross Greer (Green) West Scotland (R) Pam Gosal (Con) West Scotland (R) Paul O'Kane (Lab) West Scotland (R) Borders Rachael Hamilton (Con) Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire (C) Christine Grahame (SNP) Midlothian South, Tweeddale and Lauderdale -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 28 June 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 28 June 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 28 June 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 28 June 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 September 2021 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions followed by Scottish Government Debate: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions -

2021 MSP Spreadsheet

Constituency MSP Name Party Email Airdrie and Shotts Neil Gray SNP [email protected] Coatbridge and Chryston Fulton MacGregor SNP [email protected] Cumbernauld and Kilsyth Jamie Hepburn SNP [email protected] East Kilbride Collette Stevenson SNP [email protected] Falkirk East Michelle Thomson SNP [email protected] Falkirk West Michael Matheson SNP [email protected] Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse Christina McKelvie SNP [email protected] Motherwell and Wishaw Clare Adamson SNP [email protected] Uddingston and Bellshill Stephanie Callaghan SNP [email protected] Regional Central Scotland Richard Leonard Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Monica Lennon Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Mark Griffin Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Stephen Kerr Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Graham Simpson Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Meghan Gallacher Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Gillian Mackay Green [email protected] Constituency MSP Name Party Email Glasgow Anniesland Bill Kidd SNP [email protected] Glasgow Cathcart James Dornan SNP [email protected] Glasgow Kelvin Kaukab Stewart SNP [email protected] Glasgow Maryhill and Springburn Bob Doris SNP [email protected] -

Summer Is A-Coming in How to Get Your Outdoor Space Summer-Ready: Pages 8 & 9

Summer is a-coming in HOw tO gEt yOur OutdOOr SpAcE SummEr-rEAdy: pAgES 8 & 9 Series 2 No. 8404 Established may 1848 thursday may 13, 2021 www.eladvertiser.co.uk 80p BRIEF ING NEwS A charming and popular lady Mundell wins with a lCaonsrervgativee rertai nss Dhumfariesrshiere s eoat wfith v4,00o0 mtajeoristy ELIZABETH Calvert was born in April 1926 to Isabel, from OLIVER Mundell retained a farming family in the Dumfriesshire seat for the Oxfordshire, and John, a Scots Conservatives with an increased share Presbyterian, who had moved of the vote in last Thursday’s Scottish south for work. parliamentary election. He polled 19,487 votes (47.7%), Full story: page 4 increasing his share by 10.4 per cent. NEwS Mr Mundell told the E&L Advertiser he had not been confident after seeing Community buyouts the national polls so it had been a surprise to see his vote share go up. are good for climate His nearest rival, the SNP’s Joan McAlpine, also increased her share of the vote by 3.8 per cent and polled 15,421 (37.7%). It was a poor night for Labour and Colin Smyth took only 4,671 votes (11.4%) and saw his share of the vote fall by 13.8 per cent. COMMUNITYLand Scotland He was, once again, elected through has published research showing the regional list and remains a South that community landowners Scotland MSP. are punching well above their The fourth candidate Richard Brodie weight when it comes to tack- of the Scottish Liberal Democrats polled ling the climate emer gency. -

ANNUAL REPORT Contents

2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT Contents About the society 3 Chair's report 5 General secretary's report 6 Scottish Fabians 7 Young Fabians 8 Local Fabian societies 9 Fabian Women's Network 10 Fabians remembered 11 Year in review 12 Local Fabian society listings 14 Treasurer's report 15 Auditor's statement 16 Accounts 18 2 | Annual report 2017-18 About the society The Fabian Society is an independent left-leaning think tank and a democratic membership society with over 7,000 members. We influence political and public thinking and provide a space for broad and open-minded debate. We publish insight, analysis and opinion in print and online; conduct research and undertake major policy inquiries; convene conferences, speaker meetings and roundtables; and facilitate member de- bate and activism right across the UK. As a think tank we seek to influence political and policy debate. Our staff team in London and Edin- burgh work with a wide network of leading politicians and policy experts to develop and promote new ideas and to influence the climate of political opinion. We are also a membership society and our members are at the heart of everything we do. They set the society’s direction, through member meetings, elections and committees. They shape our programme as contributors and volunteers. And each year hundreds of activities are organised by and for our members by autonomous sections of the society – the Young Fabians, the Fabian Women’s Network, the Scottish Fabians, the Welsh Fabians – and by 50 affiliated local Fabian societies. What we stand for The Fabian Society is a socialist organisation which aims to promote: • greater equality of power, wealth and opportunity • the value of collective action and public service • an accountable, tolerant and active democracy • citizenship, liberty and human rights • sustainable development • multilateral international cooperation The society is a place for open debate where disagreement is expected and respected. -

Candidates for the 2021 May Scottish Election

Candidates for the 2021 May Scottish Election Contact Details for All Candidates can be found at https://whocanivotefor.co.uk/ Constituency - Clydesdale Claudia Beamish – Labour Amanda Jane Kubie – Liberal Democrats Eric Holford – Conservatives Màiri McAllan – SNP Regional List - South Scotland list (Not in order) SNP Labour Heather Anderson Claudia Beasmish Stacy Bradley Ian Davidson Laura Brennan-Whitefield Kevin McGregor Siobhan Brown Carol Mochan Emma Harper Katherine Sangster Màiri McAllan Colin Smyth Joan McAlpine Martin Whitfield Paul McLennan Ali Salamati Stephen Thompson Richard Walker Paul Wheelhouse Conservatives Liberal Democrats Alex Allison Catriona Bhatia Finlay Carson Richard Brodie John Denerley Euan Davidson Sharon Dowey Kirsten Herbst-Gray Brian Whittle Amanda Jane Kubie Rachael Hamilton Jenny Marr Scott Hamilton AC May Shona Haslam Alexander Herdman Eric Holford Craig Hoy Oliver Mundell Scottish Green Reform UK Dominic Ashmole Michelle Ballantyne Peter Barlow James Alexander Edward Corbett Ciara Campbell David Alexander Kirkwood Barbra Harvie William Conlin Luke Chales Strang Tristan Gray Kath Malone Candidates for the 2021 May Scottish Election Contact Details for All Candidates can be found at https://whocanivotefor.co.uk/ Regional List - South Scotland list (Not in order) Laura Moodie James Konrad Puchowski All for Unity UKIP Jamie Blackett David Blaymires George Galloway Patricia Bryant Elspeth Grindlay Richard Elvin Jim Grindlay Nick Hollis Bruce Halliday Julia Searle Malcolm AB MacDonald Pat Mountain Kirsteen -

Impact of Social Media and Screen-Use on Young People's Health

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Impact of social media and screen-use on young people’s health Fourteenth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 29 January 2019 HC 822 Published on 31 January 2019 by authority of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science and associated public bodies. Current membership Norman Lamb MP (Liberal Democrat, North Norfolk) (Chair) Vicky Ford MP (Conservative, Chelmsford) Bill Grant MP (Conservative, Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Mr Sam Gyimah MP (Conservative, East Surrey) Darren Jones MP (Labour, Bristol North West) Liz Kendall MP (Labour, Leicester West) Stephen Metcalfe MP (Conservative, South Basildon and East Thurrock) Carol Monaghan MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow North West) Damien Moore MP (Conservative, Southport) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Martin Whitfield MP (Labour, East Lothian) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/copyright. Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/science and in print by Order of the House. -

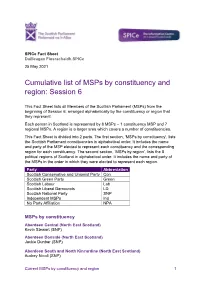

Cumulative List of Msps by Constituency and Region: Session 6

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 Cumulative list of MSPs by constituency and region: Session 6 This Fact Sheet lists all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) from the beginning of Session 6, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represent. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a number of constituencies. This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSP elected to represent each constituency and the corresponding region for each constituency. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs in the order in which they were elected to represent each region. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA MSPs by constituency Aberdeen Central (North East Scotland) Kevin Stewart (SNP) Aberdeen Donside (North East Scotland) Jackie Dunbar (SNP) Aberdeen South and North Kincardine (North East Scotland) Audrey Nicoll (SNP) Current MSPs by constituency and region 1 Aberdeenshire East (North East Scotland) Gillian Martin (SNP) Aberdeenshire West (North East Scotland) Alexander Burnett (Con) Airdrie -

The Ocean Conservation Register

The Ocean Conservation Register The Ocean Conservation Register “Growing the voice of the ocean in Westminster” www.sas.org.uk 1 The Ocean Conservation Register Published by Surfers Against Sewage June 2018 Surfers Against Sewage, Wheal Kitty Workshops, St. Agnes, Cornwall, TR5 0RD www.sas.org.uk Tel: 01872 553001 Email: [email protected] Registered Charity in England & Wales No. 1145877 (All information correct as of 25th May 2018) This report is supported by: The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation supports Surfers Against Sewage with an initiative to increase understanding of and influence on politicians’ views on marine conservation issues through the development of The Protect Our Waves All-Party Parliamentary Group. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation is an international charitable foundation with cultural, educational, social and scientific interests, based in Lisbon with offices in London and Paris. The purpose of the UK Branch in London is to bring about long-term improvements in wellbeing, particularly for the most vulnerable, by creating connections across boundaries (national borders, communities, disciplines and sectors) which deliver social, cultural and environmental value. www.sas.org.uk 2 The Ocean Conservation Register Foreword As a marine scientist and conservationist, this pollution has resulted in UK Parliament showing ambition documentation of the marine interests of MPs offers and leadership in reducing single use plastics, as one an important insight into the level of engagement of conservation challenge that everyone wants to solve. UK Parliament on ocean issues. A healthy functioning ocean is critical to our health and wellbeing, but there are UK Parliament is in a strong position to implement ocean immense and growing pressures from climate change, conservation policies and actions, informed by good overexploitation, pollution and habitat degradation and loss.