"Service Invention Should Belong to Legal Entity Approach to Revision of Patent Law Article 35 (Part I) 【2013/8/7】

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability Report 2015 Report Sustainability (April 2014–March 2015) 2014–March (April

Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation http://www.nssmc.com/en/ NSSMC’s Logotype Sustainability Report 2015 (April 2014–March 2015) The central triangle in the logo represents a blast furnace and the people who create steel. It symbolizes steel, indispensable to the advance- ment of civilization, brightening all corners of the world. The center point can be viewed as a summit, reflecting our strong will to become the world’s leading steelmaker. It can also be viewed as depth, with the vanishing point rep- resenting the unlimited future potential of steel as a material. The cobalt blue and sky blue color palette represents innovation and reliability. Image provided by Toyota Motor Corporation Image provided by East Japan Railway Company Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Sustainability Report ecoPROCESSecoecoPROCESSPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NSSMC and its printing service support Green Procurement Initiatives. Eco-friendly vegetable oil ink is used Printed in Japan for this report. +++ 革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発 eco PROCESSecoPROCESSecoPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NIPPON STEEL & SUMITOMO METAL CORPORATION Sustainability Report 2015 01 Corporate Philosophy Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Group will pursue world-leading technologies and manufacturing capabilities, and contribute to society by providing excellent products and services. Structure of the Report Management Principles Editorial policy This Sustainability Report is the 18th since the former 1. We continue to emphasize the importance of integrity and reliability in our actions. Nippon Steel Corporation issued what is the first sus- 2. We provide products and services that benefit society, and grow in partnership with our customers. NSSMC’s Businesses tainability report by a Japanese steel manufacturer, in 3. -

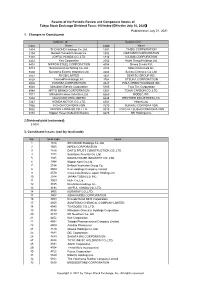

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

World's First Mass Production of Difficult-To-Form Automotive Body

May 18, 2018 World’s First Mass Production of Difficult-to-Form Automotive Body Structural Parts Using Super High Formability 980MPa Ultra High Tensile Steel - Contributing to Reduction in Body Weight of Nissan’s New Crossover - Company name: Unipres Corporation Representative: Masanobu Yoshizawa, President and Representative Director Securities code: 5949 (Tokyo Stock Exchange, First Section) Contact: Yoshio Ito, Executive Vice President Tel. +81-45-470-8755 Website: https://www.unipres.co.jp/ UNIPRES CORPORATION (Head Office: Yokohama, Kanagawa Pref., Japan; President: Masanobu Yoshizawa; hereinafter “UNIPRES”) has succeeded in the world’s first mass production of difficult-to-form car body structural parts using super high formability 980MPa (megapascal) ultra high tensile strength steel(hereinafter SHF 980MPa steel) and began supplying parts for Nissan Motor Co., Ltd.’s luxury mid-size Crossover launched in the North American market in 2018. Across the automobile industry in recent years, while weight saving of car body has been advanced due to growing demand for reductions in CO2 emissions (improving fuel efficiency) in light of preserving the global environment, higher car body strength is also desired for greater occupant protection in the event of a collision. As a result, automobile manufacturers have accelerated the use of ultra high tensile strength steel that enhances weight saving and collision safety through thickness reduction and greater strength of materials. The SHF 980MPa steel that is used for those parts ordered by Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., this time, is a new material developed by Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, and is applied to front side members, rear side members, and other under-body structural parts that are difficult to form. -

2020 Integrated Report

Integrated Report 2020 Year ended March 31, 2020 Basic Commitment of the Toshiba Group Committed to People, Committed to the Future. At Toshiba, we commit to raising the quality of life for people around The Essence of Toshiba the world, ensuring progress that is in harmony with our planet. Our Purpose The Essence of Toshiba is the basis for the We are Toshiba. We have an unwavering drive to make and do things that lead to a better world. sustainable growth of the Toshiba Group and A planet that’s safer and cleaner. the foundation of all corporate activities. A society that’s both sustainable and dynamic. A life as comfortable as it is exciting That’s the future we believe in. We see its possibilities, and work every day to deliver answers that will bring on a brilliant new day. By combining the power of invention with our expertise and desire for a better world, we imagine things that have never been – and make them a reality. That is our potential. Working together, we inspire a belief in each other and our customers that no challenge is too great, and there’s no promise we can’t fulfill. We turn on the promise of a new day. Our Values Do the right thing We act with integrity, honesty and The Essence of Toshiba comprises three openness, doing what’s right— not what’s easy. elements: Basic Commitment of the Toshiba Group, Our Purpose, and Our Values. Look for a better way We continually s trive to f ind new and better ways, embracing change With Toshiba’s Basic Commitment kept close to as a means for progress. -

March 15, 2018 Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Sanyo

March 15, 2018 Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Sanyo Special Steel Co., Ltd. Commencement of Discussions Regarding Making Sanyo Special Steel a Subsidiary of Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal and Other Matters This is to announce that Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation (President: Kosei Shindo; “NSSMC”) and Sanyo Special Steel Co., Ltd (President: Shinya Higuchi; “Sanyo Special Steel”) have commenced discussions (the “Discussions”) to explore opportunities to make Sanyo Special Steel a subsidiary of NSSMC (the “Proposed Transaction”) and to strengthen the special steel businesses of both companies. The target date of the Proposed Transaction is March 2019. The special steel businesses of both companies currently focus on markets in Asia, but NSSMC’s planned acquisition of Ovako AB (a manufacturer of special steel the headquarters of which are located in Sweden. "Ovako"), which NSSMC intends to close in the first half of 2018, will help the companies to work toward a global business promotion system, with opportunities of enhanced cooperation among NSSMC, Sanyo Special Steel, and Ovako. Regarding the acquisition of Ovako by NSSMC, please refer to the press release published today by NSSMC entitled “Regarding Acquisition of Shares in Ovako (Making It a Subsidiary).” Matters such as the specific method of the Proposed Transaction, the shareholding ratio of NSSMC in Sanyo Special Steel and other matters are yet to be discussed, and such matters will be publicly disclosed if an when an agreement is reached. Furthermore, Sanyo Special Steel will continue to be a listed company after it becomes NSSMC’s subsidiary. 1. The Goal of the Discussions Special steel is used as a material in critical parts for various industries such as those that manufacture automobiles and industrial machinery, and it is expected that demand for it shall continue to grow steadily. -

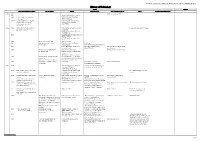

Itraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021

iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List...........................................3 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. Series 34................................................ 5 3 Further information .....................................................................................6 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 2 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List IHS Markit Ticker IHS Markit Long Name ACOM ACOM CO., LTD. JUSCO AEON CO., LTD. ANAHOL ANA HOLDINGS INC. FUJITS FUJITSU LIMITED HITACH HITACHI, LTD. HNDA HONDA MOTOR CO., LTD. CITOH ITOCHU CORPORATION JAPTOB JAPAN TOBACCO INC. JFEHLD JFE HOLDINGS, INC. KAWHI KAWASAKI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. KAWKIS KAWASAKI KISEN KAISHA, LTD. KINTGRO KINTETSU GROUP HOLDINGS CO., LTD. KOBSTL KOBE STEEL, LTD. KOMATS KOMATSU LTD. MARUB MARUBENI CORPORATION MITCO MITSUBISHI CORPORATION MITHI MITSUBISHI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. MITSCO MITSUI & CO., LTD. MITTOA MITSUI CHEMICALS, INC. MITSOL MITSUI O.S.K. LINES, LTD. NECORP NEC CORPORATION NPG-NPI NIPPON PAPER INDUSTRIES CO.,LTD. NIPPSTAA NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION NIPYU NIPPON YUSEN KABUSHIKI KAISHA NSANY NISSAN MOTOR CO., LTD. OJIHOL OJI HOLDINGS CORPORATION ORIX ORIX CORPORATION PC PANASONIC CORPORATION RAKUTE RAKUTEN, INC. RICOH RICOH COMPANY, LTD. SHIMIZ SHIMIZU CORPORATION SOFTGRO SOFTBANK GROUP CORP. SNE SONY CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 3 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List SUMICH SUMITOMO CHEMICAL COMPANY, LIMITED SUMI SUMITOMO CORPORATION SUMIRD SUMITOMO REALTY & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. TFARMA TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY LIMITED TOKYOEL TOKYO ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY HOLDINGS, INCORPORATED TOSH TOSHIBA CORPORATION TOYOTA TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 4 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. -

History of Technology

NIPPON STEEL TECHNICAL REPORT No. 101 NOVEMBER 2012 History of Technology Steel Others Raw Material/Ironmaking Steelmaking Plate Flat Products Bar and Shape Steel Pipe Stainless Steel/Titanium 1950– 1954 High-strength rail HH 1957 Aluminum killed steel HT-50 1958– Self-fluxing sinter making manufacturing technology technology (WEL-TEN ®50) 1959– Larger blast furnace, higher High-strength 60K steel for pressure, O2 enriching, welding (WEL-TEN60) high-temperature blast COR-TEN® technology 1960– 1960 Automation of material yard, Introduction of heat treatment Large-diameter spiral linepipe sinter, hot blast stove, etc. technology Corrosion-resistant 50K steel (YAWTEN 50) 1962 Weldable high-strength 80K steel (WEL-TEN 80) N-TUF type low-temperature steel 1963 Converter exhaust gas WEL-TEN100 1964 non-combustion recovery High heat input welding for Can Super ® technology shipbuilding Anti-white-rust galvanized sheet 1965 Low-temperature (50K) steel Hot-dip galvanized sheet DP wire (rod) for high-carbon 9% nickel steel Silver Alloy ® wire drawing 1966 Molten iron desulfurization Completion of weldable U-type, Z-type steel sheet pile technology KR high-strength steel WEL-TEN series EDP of plate process control 1967 Special steel refining with LD N-TUFCR 196 (5.5% Ni steel) converter Introduction of BURB technology Vacuum degassing technology Introduction of CR rolling 1969 Converter computer control technology Hot rolling roll chock Super giant H-shape technology rearrangement equipment 1970– 1970 Practical use of steel plate for Automation -

Directory of Japanese Companies Located in Texas

Directory of Japanese Companies Located in Texas Consulate-General of Japan in Houston JETRO Houston 2020.12 Directory of Japanese Companies Located in Texas Inquiries All parties interested in companies included in this directory should contact those companies directly. For inquiries regarding this directory that are not related to specific companies, please contact the following: JETRO Houston [email protected] Despite our best efforts to provide up-to-date and accurate information in this brochure, the Consulate-General of Japan in Houston and the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Houston decline any responsibility for inaccurate, incomplete, or outdated information that may be printed in this pamphlet, and expressly disclaim any liability for errors or omissions in its contents. The Consulate-General of Japan in Houston and JETRO Houston are not liable for any damages which may occur as a result of using this directory. Directory of Japanese Companies Located in Texas Greetings We would like to extend our congratulations on the publication of The appeal of Texas has grown more and more apparent to the Directory of Japanese Companies Located in Texas. Japan, as the state welcomes its companies and residents alike with open arms and a friendly “Howdy!” We would like Over the last few years, the number of Japanese companies in nothing more than to nurture those bonds of friendship. Texas has grown rapidly. The pace has been especially quick over the last 5 years, with an average annual growth rate of 8%. The This directory was created with the aim of further expanding total number of Japanese companies in Texas increased to a and deepening the partnership between Japanese and US record-high of 436, according to our own internal survey in 2019. -

Lazard Japanese Strategic Equity Fund Monthly Commentary

Lazard Japanese Strategic Equity Fund AUG Commentary 2021 Market Overview Markets were on the weak side for the rst few weeks of the month due to concerns that rapidly increasing delta variant cases around the world would side-track the current global economic recovery following pandemic period lows. However, the market made a strong recovery in the last week-and-a-half, with the TOPIX Total Return index nishing the month up a solid 3.2% in yen terms. Tokyo managed to host a reasonably successful Olympics and Japan even produced a strong showing in the medal count, particularly in gold medals. Portfolio Review During the month, the portfolio underperformed the TOPIX Total Return Index which returned 3.2% in yen terms. Being underweight and stock selection in consumer discretionary, and stock selection in the materials and utilities sectors were top contributors to performance. Being underweight and stock selection in health care, stock selection in communication services, and being underweight and stock selection in information technology sectors were negative. During the month, the top positive contributors to relative performance included: • Nippon Steel, Japan’s largest steel manufacturer, was strong after reporting better-than-expected rst-quarter earnings and raising its full-year guidance. • Mitsui O.S.K.Lines, a leading shipping company, continued to rise due to stronger-than-expected earnings and a better-than- expected dividend increase. • Makita, a leading global manufacturer of power tools, raised full-year guidance as its rst-quarter saw continued strong demand globally. • Dai-ichi Life Holdings, a leading life insurance company, rose as the yield on 10-year U.S. -

(Japan) Nippon Steel

ManagementManagement GoalsGoals andand MediumMedium--TermTerm Strategies/BusinessStrategies/Business PlanPlan June 2003 Nippon Steel Corporation Copyright (c) NIPPON STEEL Corporation 2003 All rights reserved. 0 Contents I. Steel Business ① Business Environment ② Nippon Steel’s Competitive Advantages ③ Key Issues and Strategies II. Medium-Term Financial Goals (FY2003 - FY2005) * Names of companies appearing in this presentation have been abbreviated 1 I. Steel Business 2 Nippon Steel: Progressing Into A New Phase of Earnings Growth BusinessBusiness EnvironmentEnvironment GlobalGlobal demand demand supported supported by by brisk brisk growth growth in in Southeast Southeast Asia, Asia, espec especiallyially China China CapacityCapacity limitations limitations leading leading to to favorable favorable demand demand for for high high value value-added-added products products StableStable and and firm firm steel steel prices prices due due to to tight tight supply supply caused caused by by indus industrytry consolidation consolidation GlobalGlobal steel steel commodity commodity price price convergence convergence favorable favorable for for Japanese Japanese steel steel makers makers StrategiesStrategies && GoalsGoals ExpandExpand sales sales of of high high value value-added-added products products in in growing growing markets, markets, especially especially China China CapitalizeCapitalize on on strong strong relationships relationships with with key key Japanese Japanese customers customers EstablishEstablish global global alliances -

The 88Th Term Interim Report (PDF 519KB)

The 88th Term Interim Report April 1, 2012 to September 30, 2012 Index To Our Shareholders ………………… 1 Topics …………………………………… 3 Summary of Consolidated Financial Statements … 7 Information about NSSMC shares …… 9 Securities Code: 5401 010_0299302832412.indd 2 2012/12/07 17:17:44 To Our Shareholders We would like to thank you for your continued understanding and support. On October 1, 2012, Nippon Steel Corporation (hereinafter referred to as “the former Nippon Steel”) and Sumitomo Metal Industries, Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as “the former Sumitomo Metals”), have merged to become Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation (hereinafter referred to as “NSSMC”). The climate of the steel business is changing faster and more drastically than it has ever been. Facing this challenge, we will act speedily and decisively to raise our corporate value and achieve sustainable growth. (Overview of Business Operations and Performance for the First Half of Fiscal 2012) President & COO, Tomono (left) and Chairman & CEO, Muneoka (right) We would like to present the overview of business operations during the first half of fiscal 2012 (April 1, 2012 to September 30, 2012). The slowdown of the global economy intensified during the first half of fiscal 2012 due to recessive economic conditions in Europe and slowing growth in China and other emerging economies. The Japanese economy continued to gradually recover as consumer spending and private capital investment remained favorable despite being influenced by the persistently record-high yen and the slowdown in overseas economies. Under such an environment, domestic demand for steel remained relatively constant due to solid demand for construction and automobile manufacturing, despite a large decrease in demand for use in shipbuilding. -

Fukushima Experimental Offshore Floating Wind Farm Project Second Phase Update

October 30, 2014 Marubeni Corporation The University of Tokyo Mitsubishi Corporation Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Japan Marine United Corporation Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Hitachi, Ltd. Furukawa Electric Co., Ltd. Shimizu Corporation Mizuho Information & Research Institute, Inc. Fukushima Experimental Offshore Floating Wind Farm Project Second Phase Update A consortium comprised of Marubeni (project integrator), the University of Tokyo (technical advisor), Mitsubishi, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Japan Marine United, Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding, Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, Hitachi, Furukawa Electric, Shimizu, and Mizuho Information & Research, has been participating in an experimental offshore floating wind farm project sponsored by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry since March 2012. Preparatory works for the installation of the 7MW oil pressure drive-type wind turbine on the three-column semi-sub floater at Onahama port, Fukushima, are almost completed and delivery of the floater from Nagasaki to Onahama has started today as part of the second term. 1. Outline of construction works in the second term: Assembly and setting of two units of the 7MW oil pressure drive-type floating wind turbines, delivery of the facilities to the testing area, and connection to the undersea cable. 2. Work progress to date: <7MW oil pressure drive-type floating wind turbine> Floater Delivery of the three-column semi-sub floater from Nagasaki to Onahama port is in progress. Wind Turbine Construction of the nacelle for the 7MW oil pressure drive-type wind turbine is in progress at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Yokohama Dockyard & Machinery Works. Construction of the tower for 7MW oil pressure drive-type floating wind turbine is in progress at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd.