[Preliminary Draft for the Jilfa Symposium Paper Workshop]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

Sustainability Report 2015 Report Sustainability (April 2014–March 2015) 2014–March (April

Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation http://www.nssmc.com/en/ NSSMC’s Logotype Sustainability Report 2015 (April 2014–March 2015) The central triangle in the logo represents a blast furnace and the people who create steel. It symbolizes steel, indispensable to the advance- ment of civilization, brightening all corners of the world. The center point can be viewed as a summit, reflecting our strong will to become the world’s leading steelmaker. It can also be viewed as depth, with the vanishing point rep- resenting the unlimited future potential of steel as a material. The cobalt blue and sky blue color palette represents innovation and reliability. Image provided by Toyota Motor Corporation Image provided by East Japan Railway Company Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Sustainability Report ecoPROCESSecoecoPROCESSPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NSSMC and its printing service support Green Procurement Initiatives. Eco-friendly vegetable oil ink is used Printed in Japan for this report. +++ 革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発 eco PROCESSecoPROCESSecoPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NIPPON STEEL & SUMITOMO METAL CORPORATION Sustainability Report 2015 01 Corporate Philosophy Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Group will pursue world-leading technologies and manufacturing capabilities, and contribute to society by providing excellent products and services. Structure of the Report Management Principles Editorial policy This Sustainability Report is the 18th since the former 1. We continue to emphasize the importance of integrity and reliability in our actions. Nippon Steel Corporation issued what is the first sus- 2. We provide products and services that benefit society, and grow in partnership with our customers. NSSMC’s Businesses tainability report by a Japanese steel manufacturer, in 3. -

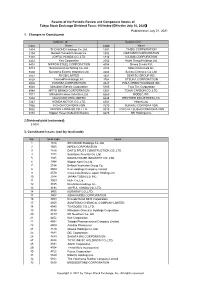

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

World's First Mass Production of Difficult-To-Form Automotive Body

May 18, 2018 World’s First Mass Production of Difficult-to-Form Automotive Body Structural Parts Using Super High Formability 980MPa Ultra High Tensile Steel - Contributing to Reduction in Body Weight of Nissan’s New Crossover - Company name: Unipres Corporation Representative: Masanobu Yoshizawa, President and Representative Director Securities code: 5949 (Tokyo Stock Exchange, First Section) Contact: Yoshio Ito, Executive Vice President Tel. +81-45-470-8755 Website: https://www.unipres.co.jp/ UNIPRES CORPORATION (Head Office: Yokohama, Kanagawa Pref., Japan; President: Masanobu Yoshizawa; hereinafter “UNIPRES”) has succeeded in the world’s first mass production of difficult-to-form car body structural parts using super high formability 980MPa (megapascal) ultra high tensile strength steel(hereinafter SHF 980MPa steel) and began supplying parts for Nissan Motor Co., Ltd.’s luxury mid-size Crossover launched in the North American market in 2018. Across the automobile industry in recent years, while weight saving of car body has been advanced due to growing demand for reductions in CO2 emissions (improving fuel efficiency) in light of preserving the global environment, higher car body strength is also desired for greater occupant protection in the event of a collision. As a result, automobile manufacturers have accelerated the use of ultra high tensile strength steel that enhances weight saving and collision safety through thickness reduction and greater strength of materials. The SHF 980MPa steel that is used for those parts ordered by Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., this time, is a new material developed by Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, and is applied to front side members, rear side members, and other under-body structural parts that are difficult to form. -

The Question of War Reparations in Polish-German Relations After World War Ii

Patrycja Sobolewska* THE QUESTION OF WAR REPARATIONS IN POLISH-GERMAN RELATIONS AFTER WORLD WAR II DOI: 10.26106/gc8d-rc38 PWPM – Review of International, European and Comparative Law, vol. XVII, A.D. MMXIX ARTICLE I. Introduction There is no doubt that World War II was the bloodiest conflict in history. Involv- ing all the great powers of the world, the war claimed over 70 million lives and – as a consequence – has changed world politics forever. Since it all started in Poland that was invaded by Germany after having staged several false flag border incidents as a pretext to initiate the attack, this country has suffered the most. On September 17, 1939 Poland was also invaded by the Soviet Union. Ultimately, the Germans razed Warsaw to the ground. War losses were enormous. The library and museum collec- tions have been burned or taken to Germany. Monuments and government buildings were blown up by special German troops. About 85 per cent of the city had been destroyed, including the historic Old Town and the Royal Castle.1 Despite the fact that it has been 80 years since this cataclysmic event, the Polish government has not yet received any compensation from German authorities that would be proportionate to the losses incurred. The issue in question is still a bone of contention between these two states which has not been regulated by both par- ties either. The article examines the question of war reparations in Polish-German relations after World War II, taking into account all the relevant factors that can be significant in order to resolve this problem. -

2020 Integrated Report

Integrated Report 2020 Year ended March 31, 2020 Basic Commitment of the Toshiba Group Committed to People, Committed to the Future. At Toshiba, we commit to raising the quality of life for people around The Essence of Toshiba the world, ensuring progress that is in harmony with our planet. Our Purpose The Essence of Toshiba is the basis for the We are Toshiba. We have an unwavering drive to make and do things that lead to a better world. sustainable growth of the Toshiba Group and A planet that’s safer and cleaner. the foundation of all corporate activities. A society that’s both sustainable and dynamic. A life as comfortable as it is exciting That’s the future we believe in. We see its possibilities, and work every day to deliver answers that will bring on a brilliant new day. By combining the power of invention with our expertise and desire for a better world, we imagine things that have never been – and make them a reality. That is our potential. Working together, we inspire a belief in each other and our customers that no challenge is too great, and there’s no promise we can’t fulfill. We turn on the promise of a new day. Our Values Do the right thing We act with integrity, honesty and The Essence of Toshiba comprises three openness, doing what’s right— not what’s easy. elements: Basic Commitment of the Toshiba Group, Our Purpose, and Our Values. Look for a better way We continually s trive to f ind new and better ways, embracing change With Toshiba’s Basic Commitment kept close to as a means for progress. -

March 15, 2018 Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Sanyo

March 15, 2018 Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Sanyo Special Steel Co., Ltd. Commencement of Discussions Regarding Making Sanyo Special Steel a Subsidiary of Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal and Other Matters This is to announce that Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation (President: Kosei Shindo; “NSSMC”) and Sanyo Special Steel Co., Ltd (President: Shinya Higuchi; “Sanyo Special Steel”) have commenced discussions (the “Discussions”) to explore opportunities to make Sanyo Special Steel a subsidiary of NSSMC (the “Proposed Transaction”) and to strengthen the special steel businesses of both companies. The target date of the Proposed Transaction is March 2019. The special steel businesses of both companies currently focus on markets in Asia, but NSSMC’s planned acquisition of Ovako AB (a manufacturer of special steel the headquarters of which are located in Sweden. "Ovako"), which NSSMC intends to close in the first half of 2018, will help the companies to work toward a global business promotion system, with opportunities of enhanced cooperation among NSSMC, Sanyo Special Steel, and Ovako. Regarding the acquisition of Ovako by NSSMC, please refer to the press release published today by NSSMC entitled “Regarding Acquisition of Shares in Ovako (Making It a Subsidiary).” Matters such as the specific method of the Proposed Transaction, the shareholding ratio of NSSMC in Sanyo Special Steel and other matters are yet to be discussed, and such matters will be publicly disclosed if an when an agreement is reached. Furthermore, Sanyo Special Steel will continue to be a listed company after it becomes NSSMC’s subsidiary. 1. The Goal of the Discussions Special steel is used as a material in critical parts for various industries such as those that manufacture automobiles and industrial machinery, and it is expected that demand for it shall continue to grow steadily. -

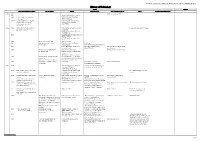

Itraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021

iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List...........................................3 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. Series 34................................................ 5 3 Further information .....................................................................................6 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 2 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List IHS Markit Ticker IHS Markit Long Name ACOM ACOM CO., LTD. JUSCO AEON CO., LTD. ANAHOL ANA HOLDINGS INC. FUJITS FUJITSU LIMITED HITACH HITACHI, LTD. HNDA HONDA MOTOR CO., LTD. CITOH ITOCHU CORPORATION JAPTOB JAPAN TOBACCO INC. JFEHLD JFE HOLDINGS, INC. KAWHI KAWASAKI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. KAWKIS KAWASAKI KISEN KAISHA, LTD. KINTGRO KINTETSU GROUP HOLDINGS CO., LTD. KOBSTL KOBE STEEL, LTD. KOMATS KOMATSU LTD. MARUB MARUBENI CORPORATION MITCO MITSUBISHI CORPORATION MITHI MITSUBISHI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. MITSCO MITSUI & CO., LTD. MITTOA MITSUI CHEMICALS, INC. MITSOL MITSUI O.S.K. LINES, LTD. NECORP NEC CORPORATION NPG-NPI NIPPON PAPER INDUSTRIES CO.,LTD. NIPPSTAA NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION NIPYU NIPPON YUSEN KABUSHIKI KAISHA NSANY NISSAN MOTOR CO., LTD. OJIHOL OJI HOLDINGS CORPORATION ORIX ORIX CORPORATION PC PANASONIC CORPORATION RAKUTE RAKUTEN, INC. RICOH RICOH COMPANY, LTD. SHIMIZ SHIMIZU CORPORATION SOFTGRO SOFTBANK GROUP CORP. SNE SONY CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 3 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List SUMICH SUMITOMO CHEMICAL COMPANY, LIMITED SUMI SUMITOMO CORPORATION SUMIRD SUMITOMO REALTY & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. TFARMA TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY LIMITED TOKYOEL TOKYO ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY HOLDINGS, INCORPORATED TOSH TOSHIBA CORPORATION TOYOTA TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 4 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. -

History of Technology

NIPPON STEEL TECHNICAL REPORT No. 101 NOVEMBER 2012 History of Technology Steel Others Raw Material/Ironmaking Steelmaking Plate Flat Products Bar and Shape Steel Pipe Stainless Steel/Titanium 1950– 1954 High-strength rail HH 1957 Aluminum killed steel HT-50 1958– Self-fluxing sinter making manufacturing technology technology (WEL-TEN ®50) 1959– Larger blast furnace, higher High-strength 60K steel for pressure, O2 enriching, welding (WEL-TEN60) high-temperature blast COR-TEN® technology 1960– 1960 Automation of material yard, Introduction of heat treatment Large-diameter spiral linepipe sinter, hot blast stove, etc. technology Corrosion-resistant 50K steel (YAWTEN 50) 1962 Weldable high-strength 80K steel (WEL-TEN 80) N-TUF type low-temperature steel 1963 Converter exhaust gas WEL-TEN100 1964 non-combustion recovery High heat input welding for Can Super ® technology shipbuilding Anti-white-rust galvanized sheet 1965 Low-temperature (50K) steel Hot-dip galvanized sheet DP wire (rod) for high-carbon 9% nickel steel Silver Alloy ® wire drawing 1966 Molten iron desulfurization Completion of weldable U-type, Z-type steel sheet pile technology KR high-strength steel WEL-TEN series EDP of plate process control 1967 Special steel refining with LD N-TUFCR 196 (5.5% Ni steel) converter Introduction of BURB technology Vacuum degassing technology Introduction of CR rolling 1969 Converter computer control technology Hot rolling roll chock Super giant H-shape technology rearrangement equipment 1970– 1970 Practical use of steel plate for Automation -

Legal Issues in the United Nations Compensation Commission on Iraq

Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.14, 2013 Legal Issues in the United Nations Compensation Commission on Iraq Monday Dickson Department of Political Science, Akwa Ibom State University, Obio Akpa Campus, P. M. B. 1167,Uyo, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article is a comprehensive interrogation of the legality or otherwise of the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) on Iraq; its establishment, operations and manifestations as the very first war reparation facility adopted by the Security Council on the basis of Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, and making it binding on an aggressor State. The paper argued that the UNCC, which is an interesting example of the institutionalisation of the United Nations compensation mechanism, is unprecedented in the UN’s compensation experience, in many respect. Although the design of the UNCC, however, fell within the tradition of war reparation facilities, in some respect, its operations, particularly subjecting the whole economy of Iraq to international control violated Iraq’s sovereignty. The paper concludes that despite the lacuna, the design of the UNCC would serve as a model for future compensation schemes. Keywords: Iraq, Compensation, Reparation, United Nations, UNCC, International Law. 1. Introduction Traditionally, under international law, a State that has violated the right of another is obligated to pay “appropriate compensation” or to make “reasonable reparation” to the victim State, besides providing guarantees against non-repetition and assurances in favour of discontinuance of the wrongful act (Eminue, 1999). According to Article 50 of the 1949 Geneva Convention I, Article 51 of the 1949 Geneva Convention II and Article 147 of the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (the Fourth Convention) “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly” are grave breaches. -

Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific Ap Ct Syrus Jin

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Research Spring 5-2019 The aC sualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific aP ct Syrus Jin Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Korean Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jin, Syrus, "The asC ualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific aP ct" (2019). Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses. 14. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd/14 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Casualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific Pact By Syrus Jin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors in History In the College of Arts and Sciences Washington University in St. Louis Advisor: Elizabeth Borgwardt 1 April 2019 © Copyright by Syrus Jin, 2019. All Rights Reserved. Jin ii Dedicated to the members of my family: Dad, Mom, Nika, Sean, and Pebble. ii Jin iii Abstract From August 1945 to September 1951, the United States had a unique opportunity to define and frame how it would approach its foreign relations in the Asia-Pacific region. -

The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles When America and her allies (known as the Triple Entente) sat down at the negotiating table with Germany, they did so with absolute power. That is, if the Germans refused any part of the unconditional surrender, the Entente would occupy Germany and end its newly-found statehood. Unwilling to risk this, Germany was forced to succumb to a number of harsh, infuriating demands. Some say that the Versailles Treaty was too harsh to allow Germany to reintegrate itself into a “new” post-war Europe, but too weak to completely destroy Germany’s ability to make war. It is on the Treaty of Versailles that most historians place the blame for Hitler’s ascent and for World War II. Woodrow Wilson was a very, very liberal (some believe nearly socialist) president in a time where progressivism was the fad. He submitted 14 points that he believed the German government should submit to. One member of the Entente’s delegation joked “The Good Lord only needed 10 commandments, Wilson needs 14.” Wilson believed that the total aim of the peace treaty should be to prevent war from ever again happening. In order to encourage a German surrender, Wilson promised a treaty that would go fairly light on Germany. For better or worse, he was unable to deliver on this promise due to America’s relative lack of involvement in the war (we got involved very near the end and sent very few troops)—which had as its result America’s loss of bargaining power and influence among the Entente.