Strategies of the New Hindu Religious Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care By

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care by © Rebecca Cairns A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, Memorial University, Religious Studies Memorial University of Newfoundland August, 2020 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABstract In the midst of environmental degradation, Religious Studies scholars have begun to assess whether or not religious traditions contain ecological resources which may initiate the restructuring of human-nature relationships. In this thesis, I explore whether it is possible to locate within Hindu religious traditions, especially lived Hindu traditions, an environmental ethic. By exploring the arguments made by scholars in the fields of Religion and Ecology, I examine both the ecological “paradoxes” seen by scholars to be inherent to Hindu ritual practice and the ways in which forms of environmental care exist or are developing within lived religion. I do the latter by examining the efforts that have been made by the Bishnoi, the Chipko Movement, Swadhyay Parivar and Bhils to conserve and protect local ecologies and sacred landscapes. ii Acknowledgements I express my gratitude to the supportive community that I found in the Department of Religious Studies. To Dr. Patricia Dold for her invaluable supervision and continued kindness. This project would not have been realized without her support. To my partner Michael, for his continued care, patience, and support. To my friends and family for their encouragement. iii List of Figures Figure 1: Inverted Tree of Life ……………………. 29 Figure 2: Illustration of a navabatrikā……………………. 34 Figure 3: Krishna bathing with the Gopis in the river Yamuna. -

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

New Age in Norway 307

New Age in Norway 307 Chapter 38 New Age in Norway New Age in Norway Ingvild Sælid Gilhus New Age up to the 1970s The background of the New Age in Norway was, like in other countries, the countercultural movement of the late 1960s, characterised by political radical- ism, the anti-war movement, hippie culture, the use of psychoactive drugs, pop music, a growing ecological awareness, and an interest in Asian religions. In the early 1970s, New Religious Movements of Asian provenance such as Hare Krishna (ISKCON), Ananda Marga, the Divine Light Mission of guru Maharaji Ji, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation as well as the Western, sufi-inspired Eckankar and the Christian-inspired Children of God had representatives in Norway. Through information meetings and courses, for instance at the universities, the representatives of these movements contrib- uted to increase the general awareness of Eastern religions and to nourish countercultural religious syncretism and alternative spirituality in Norwegian youth culture. In the 1970s there existed several distribution centres for alternative thought and lifestyle, including religious ones. Most important among them were the countercultural work communes in Hjelmsgata 1 in Oslo and on Karlsøy in Troms. In 1976 Karma Tashi Ling, a centre for Tibetan Buddhism, was opened in Oslo. It attracted people from countercultural milieus as well as Buddhists. Magazines and periodicals were important vehicles for alternative thought in the 1970s when thirty-six different titles, most of them short-lived, were pub- lished (Ahlberg 1980: 221). The most important were Vibra (appearing in 1969), Gateavisa (the Street Paper, published 1970-), Vannbæreren (Aquarius, 1974– 78), Arken (1978–1989) and Josefine (1971–1977). -

Ananda Katha

ANANDA KATHA BY NAGINA PRASAD CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter One October 1953: My friend Chandranathji and my vision of Baba. Baba sends His blessings and accepts me as a disciple. My initiation in November 1953 2 Chapter Two I am persecuted by my boss. Baba explains the real meaning of ahim’sa and the importance of iis’t’a mantra. 9 Chapter Three Jamalpur and the tiger’s grave. 11 Chapter Four Baba explains the meaning of varn’aghdana and warns against mean mindedness. The downfall of my persecutor. 15 Chapter Five February 1954: I get a sympathetic boss and am transferred to Begusarai. Manan Prasad miraculously loses weight. 19 Chapter Six Rainy Season 1954: My boss Asthanaji takes initiation and Baba appears before him. 22 Chapter Seven September 1954: Baba gives me the boon of only getting demotion when I myself desire it. My daughter dies and is miraculously resurrected and my wife takes initiation. 26 Chapter Eight The sufi saint Dattaji and his prophecy about Baba 30 Chapter Nine Winter 1954: Baba solves my difficulties in meditation and explains how His assistance is given from a distance. Shyam Charan Lahiri becomes ‘Vajra Bhairav’ at the tiger’s grave. Baba’s disciples of His previous lives. The ‘white lady’. The power and use of iis’t’a and guru mantras. Bindeshwariji’s daughter is initiated and her life is extended. My methods of pracar. 33 Chapter Ten November 1954: Demonstrations. Sunday 7th: Samadhis Sunday 14th Savikalpa and Nirvikalpa samadhi. Sunday 21st: Demonstration of death. Sunday 28th: Nirvikalpa samadhi. 42 Chapter Eleven Deep Narayanji and Vishvanathji are initiated and I try to feed Harisadhanji. -

Vedanta's Message for Our Time: Man's Need for the Eternal

Vedanta’s Message For Our Time: Man’s Need For The Eternal Philosophy By Swami Tathagatananda Since the advent of Shri Ramakrishna on the spiritual horizon of mankind, a new epoch of spiritual fraternity had been steadily unfolding. The West has been evincing its keen interest in the ancient truth of India’s heritage. Shri Ramakrishna demonstrated the reality of Divinity by realizing the Truth in his own life. This re-authentication of the ancient truths in the life of Shri Ramakrishna is a great example of hope and inspiration. Shri Ramakrishna proclaimed the fundamental unity of all religions to a world plagued by hostility, disharmony and persecution, all in the name of religion. Swami Vivekananda broadcast that teaching to the world when religious truths and the subjects of God, Soul and immortality had lost their reality and made a mockery of religion. Various dogmatic theologies with their anti-rational and anti-humanistic attitudes had denigrated the image of religion, which was ultimately abandoned in the modern period. In that bleak, hostile world, Swami Vivekananda preached the sublime truth of Vedanta that speaks of man’s spiritual depth and dimension. He taught about a new image of man as potentially Divine. According to Marie Louise Burke, “As Swamiji later wrote to Swami Ramakrishnananda, ‘I am careering all over the country. Wherever the seed of his power will fall, there it will fructify—be it today, or in a hundred years.’ . Throughout his life, wherever he was and whatever he was outwardly doing, he permanently lifted the consciousness of all with whom he came in contact. -

SWAMI YOGANANDA and the SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP a Successful Hindu Countermission to the West

STATEMENT DS213 SWAMI YOGANANDA AND THE SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP A Successful Hindu Countermission to the West by Elliot Miller The earliest Hindu missionaries to the West were arguably the most impressive. In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (1863 –1902), a young disciple of the celebrated Hindu “avatar” (manifestation of God) Sri Ramakrishna (1836 –1886), spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago and won an enthusiastic American following with his genteel manner and erudite presentation. Over the next few years, he inaugurated the first Eastern religious movement in America: the Vedanta Societies of various cities, independent of one another but under the spiritual leadership of the Ramakrishna Order in India. In 1920 a second Hindu missionary effort was launched in America when a comparably charismatic “neo -Vedanta” swami, Paramahansa Yogananda, was invited to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, sponsored by the Unitarian Church. After the Congress, Yogananda lectured across the country, spellbinding audiences with his immense charm and powerful presence. In 1925 he established the headquarters for his Self -Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles on the site of a former hotel atop Mount Washington. He was the first Eastern guru to take up permanent residence in the United States after creating a following here. NEO-VEDANTA: THE FORCE STRIKES BACK Neo-Vedanta arose partly as a countermissionary movement to Christianity in nineteenth -century India. Having lost a significant minority of Indians (especially among the outcast “Untouchables”) to Christianity under British rule, certain adherents of the ancient Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism retooled their religion to better compete with Christianity for the s ouls not only of Easterners, but of Westerners as well. -

9 Spiritual Development: Meaning and Purpose9

Huitt, W., & Robbins, J. (2018). Spiritual development: Meaning and purpose. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 159-178). La Vergne, TN: IngramSpark. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-09-huitt-robbins- brilliant-star-spiritual.pdf SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT 9 Spiritual Development: Meaning and Purpose9 William G. Huitt and Jennifer L. Robbins Spirituality is a difficult concept to define. While it has been explored throughout human history as one of the three fundamental aspects of human beings (ie, body, mind, spirit) (Huitt, 2010b), there is widespread disagreement as to its origin, functioning, or even importance (Huitt, 2000). However, in a broad perspective, spirituality deals fundamentally with how human beings approach the unknowns of life, how we define and relate to the sacred. Spirituality is considered by many psychologists to be an inherent property of the human being (Helminiak, 1996; Newberg, D’Aquili, & Rause, 2001). From this viewpoint, human spirituality is an attempt to understand and connect to the unknowns of the universe or search for meaningfulness in one’s life (Adler, 1980; Frankl, 1998). Likewise, Weaver and Cotrell (1992) proposed that spirituality “refers to matters of ultimate concern that call for releasing the passions of the soul to search for goals with personal meaning” (p. 1). Other definitions include a relationship with the sacred (Beck & Walters, 1977), “an individual's experience of and relationship with a fundamental, nonmaterial aspect of the universe” (Tolan, 2002). Others view soul or spirit as a description of the “vital principle or animating force believed to be within living beings” (Zinn, 1997, p. -

ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22

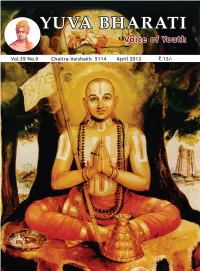

Vol.39 No.9 Chaitra-Vaishakh 5114 April 2012 R.15/- Editorial 03 Swami Vivekananda on his return to India-13 A Gigantic Plan 05 Fashion Man ... Role in Freedom Struggle 11 Sister Nivedita : Who Gave Her All to India-15 15 ANNA HAZARE Jai Jawan to Jaikisan 22 The Role of Saints In Building And Rebuilding Bharat 26 V.Senthil Kumar Sangh Inspired by Swamiji 32 Vivekananda Kendra Samachar 39 Single Copy R.15/- Annual R.160/- For 3 Yrs R.460/- Life (10 Yrs) R.1400/- Foreign Subscription: Annual - $40 US Dollar Life (10 years) - $400US Dollar (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) Yuva bharati - 1 - April 2012 Invocation çaìkaraà çaìkaräcäryaà keçavaà bädaräyaëam| sütrabhäñyakåtau vande bhagavantau punaù punaù|| I salute, again and again, the great teacher Aadi Shankaracharya, who is Lord Siva and Badarayana, who is Lord Vishnu, the venerable ones who wrote the Bhaashyaas and the Brahma-Sutras respectively. Yuva bharati - 2 - April 2012 Editorial Youth Icon… hroughout modern history youths have needed an icon. Once there were the Beetles; then there was John Lennon. TFor those youngsters who love martial arts there was Bruce Lee followed by Jackie Chan. Now in the visible youth culture of today who is the youth icon? The honest answer is Che Guevara. The cigar smoking good looking South American Marxist today looks at us from every T-shirt and stares from beyond his grave through facebook walls. Cult of Che Guevara is marketed in the every conceivable consumer item that a youth may use. And he has been a grand success. -

Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, B. (2005). Daniels, B. (2005). Nondualism and the divine domain. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24(1), 1–15.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2005.24.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels This paper claims that the ultimate issue confronting transpersonal theory is that of nondual- ism. The revelation of this spiritual reality has a long history in the spiritual traditions, which has been perhaps most prolifically advocated by Ken Wilber (1995, 2000a), and fully explicat- ed by David Loy (1998). Nonetheless, these scholarly accounts of nondual reality, and the spir- itual traditions upon which they are based, either do not include or else misrepresent the reve- lation of a contemporary spiritual master crucial to the understanding of nondualism. Avatar Adi Da not only offers a greater differentiation of nondual reality than can be found in contem- porary scholarly texts, but also a dimension of nondualism not found in any previous spiritual revelation. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

Leaving the Spiritual Teacher Behind to Directly Embrace Nondual Being

FINDING THE LION’S ROAR THROUGH NONDUAL PSYCHOTHERAPY: Leaving the spiritual teacher behind to directly embrace nondual being. Written by Gary Nixon – Paradoxica: Journal of Nondual Psychology, Vol. 4: Spring 2012 Summary This article is a summary of a nondual psychotherapy session with a long time spiritual seeker of 40 years who had worked hard on a meditative path with a guru, but had not experienced an awakening. In the session, he is introduced to some nondual pointers to help him realize that it is all available right here, right now, he has to only see it. Over reliance on another, letting go of effort, embracing no knowing, realizing nothing can be done, coming to the end of seeking and stopping, sitting in one’s own awareness, abiding in consciousness, and taking the ultimate medicine are all reviewed to invite the long term seeker to see “this is it.” Gary Nixon, Ph.D. is a nondual transpersonal psychologist and an Associate Professor in Addictions Counselling at the University of Lethbridge. He was drawn to eastern contemplative traditions after an existential world collapse in the early 1980’s. After a tour through many eastern teachers such as Osho, Krishnamurti, Nisargadatta, and Papaji, he completed his Master’s and doctorate in Counselling Psychology and embraced the work of Ken Wilber and A.H. Almaas. He has had a nondual psychology private practice and been facilitating nondual groups over the last ten years. 2 Deconstructing Reliance on the Awakened Other I received the call from Tim (a pseudonym). He reported 40 years of intense Buddhist meditation in a Buddhist community with an enlightened teacher, all of the years trying to become enlightened, but still no awakening. -

The Star of Yoga Guidance from the Light

The Star of Yoga Guidance from the Light (From an upcoming book “Meditation For the Monkey Mind”) By Mas Vidal As we look up to the night sky we get a spectacular glimpse of the vast galaxy we see from earth. Stars abound through out the sky like mini suns each creating their own distinct light, some forming clusters and interesting configurations. There is an inherent quality in humanity to feel an attraction to light, be it sunlight or open spaces. It makes sense as we have come to understand the science behind energy we know that like attracts like. We realize there is great value that comes from being in the light, which breeds an optimism and greater awareness. In general people feel a kinship towards one another when they share something in common. A star’s light is symbolic of the highest ideal of every human being to live in love, light and harmony (sat, chit andanda) with nature and all aspects of life. The ancients have always looked to the stars for guidance, healing and understanding the cycles of nature. A star’s five points symbolize a connection to the five great elements (pancha maha bhutas) and reflects the gradation of energy from gross (earth) to subtle (sky). The mystical star of yoga provides guidance on the journey towards enlightenment as various pathways, with each empowering us to reach the culmination or purna as the true yogic ideal of living a fully integrated lifestyle. Such integration is based on a balance between spirit and ecology thus reminding us of the importance of responsibility in our thoughts, words and actions that can either connect us or create greater divide from the Divine.