Are We Comparing Yet?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

1998 Education

1998 Education JANUARY JUNE 11 Video: Alfred Steiglitz: Photographer 2–5 Workshop: Drawing for the Doubtful, Earnest Ward, artist 17 Teacher Workshop: The Art of Making Books 3 Video: Masters of Illusion 18 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove’s Nature Abstraction, 10 Video: Cezanne: The Riddle of the Bathers Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 17 Video: Mondrian 25 Members Preview: O’Keeffe and Texas 21 Gallery Talk: Nature and Symbol: Impressionist and 26 Colloquium: The Making of the O’Keeffe and Texas Post-impressionism Prints from the McNay Collection, Exhibition, Sharyn Udall, Art Historian, William J. Chiego, Lyle Williams, Curator, Prints and Drawings Director, Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 22 Lecture and Members Preveiw: The Garden Setting: Nature Designed, Linda Hardberger, Curator of the Tobin FEBRUARY Collection of Theatre Arts 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 24 Teacher Workshop: Arts in Education, Getty 8 Video: Georgia O’Keeffe: The Plains on Paper Education Institute 12 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe and American Nature, Charles C. Eldredge, title? JULY 15 Video: Alfred Stieglitz: Photographer 7 Members Preview: Kent Rush Retrospective 21 Symposium: O’Keeffe in Texas 12 Gallery Talk: A Discourse on the Non-discursive, Kent Rush, artist MARCH 18 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 19 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 8 Lunch and Lecture: A Photographic Affair: Stieglitz’s 26 Gallery Talk: Kent Rush Retrospective, Lyle Williams, Portraits -

Bam 2016 Annual Report

BAM 2016 2 1ANNUAL REPORT 0 6 BAM’s mission is to be the home for adventurous artists, audiences, and ideas. 3—6 Community, 31–33 GREETINGS DanceMotion USASM, 34–35 Chair Letter, 4 Visual Art, 36–37 President & Executive Producer’s Letter, 5 Membership, 38 BAM Campus, 6 Membership, 37—39 7—35 40—47 WHAT WE DO WHO WE ARE 2015 Next Wave Festival, 8–10 BAM Board, 41 2016 Winter/Spring Season, 11–13 BAM Supporters, 42–45 Also On Stage, 14 BAM Staff, 46–47 BAM Rose Cinemas, 15–20 48—50 First-run Films, 16 NUMBERS BAMcinématek, 17–18 BAM Financial Statements, 49–50 BAMcinemaFest, 19 HD Screenings, 20 51—55 BAMcafé Live, 21–22 THE TRUST BAM Hamm Archives, 23 BET Chair Letter, 52 Digital Media, 24 BET Donors, 53 Education & Humanities, 25–30 BET Financial Statements, 54–55 2 TKTKTKTK Cover: Urban Bush Women in Walking with ‘Trane| Photo: Julieta Cervantes Greetings GREETINGS 3 TKTKTKTK 2016 Winter/Spring | Royal Shakespeare Company in Henry IV Part I | Photo: Richard Termine Change is anticipated, expected, welcomed. — Alan H. Fishman Dear Friends, As you all know, and perhaps celebrated (!), Anne Bogart, Ivo van Hove, Long time trustee Beth Rudin Dewoody As I end my leadership role, I want to I stepped down as chairman of this William Kentridge, and many others. became an honorary trustee. Mark Jackson express my thanks to all I have met and miraculous institution effective December and Danny Simmons, both great trustees, worked with along the way. Together we have 31, 2016. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make Your Way): a Conversation with Amandine Gay

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 16 Issue 16 Spring/Fall 2019 Article 2 Fall 2019 Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make Your Way): A Conversation with Amandine Gay Anupama Arora University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, [email protected] Sandrine Sanos Texas A&M University- Corpus Christi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Africana Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Arora, Anupama, and Sandrine Sanos. 2020. "Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make Your Way): A Conversation with Amandine Gay." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 16 (Fall): 17-38. 10.23860/jfs.2019.16.02. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arora and Sanos: Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make Your Way): A Conversation with Aman Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make Your Way): A Conversation with Amandine Gay Anupama Arora, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Sandrine Sanos, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Copyright by Anupama Arora and Sandrine Sanos Amandine Gay Photo by Christin Bela of CFL Group Photography Introduction and Commentary “I’m French and I’m staying here … My kids will stay here too, and we’ll be here a while … I’m not going anywhere.” Afro-feminist French filmmaker Amandine Gay’s 2017 documentary film Ouvrir La Voix (Speak Up/Make you Way) ends with this unequivocal assertion, this claiming of French-ness and France as home, by one of the Black-French interviewees in the film. -

Films for Spanish and Latin American Studies at Dupré Library

Films for Spanish and Latin American Studies at Dupré Library List created Fall 2007 by Carmen Orozco, Richard Winters, and Leslie Bary (Department of Modern Languages). Major funds for the enhancement of the Latin American film collections at Dupré from BORSF / LEQSF Enhancement Grant (2006-2007) ENH-TR-75 (P.I. L. Bary, Co-P.I.s D. Barry, I. Berkeley, J. Frederick, C. Grimes, B. Kukainis, R. Winters). 25 watts PN1997 .T94 2004 DVD Director: Juan Pablo Rebella and Pablo Stoll. Spanish with English subtitles. [2004] This affable low-budget affair from Uruguay captures a day in the life of three friends--Leche (Daniel Handler), Javi (Jorge Temponi), and Seba (Alfonso Tort)--as they bumble their way through a lazy, hungover Saturday in Montevideo. Along the way, they encounter a series of bizarre characters who remind them of just how unfocused and boring their lives actually are. Directed under the influence of American indie auteurs such as Jim Jarmusch and Richard Linklater by Juan Pablo Rebella and Pablo Stoll, 25 WATTS is a universally charming comedy.—www.rottentomatoes.com [94 minutes] 90 miles E184 .C97 N56 2003 DVD E184 .C97 N56 2001 VIDEO Director: Juan Carlos Zaldívar. Spanish and English. [2003] "A Cuban-born filmmaker recounts the strange fate that brought him as a groomed young communist to exile in Miami in 1980 during the dramatic Mariel boatlift. The story of an immigrant family and how the historical forces around them shaped their personal relationships and attitudes towards the world around them"--Container. [53 minutes] 1932, Cicatriz de la Memoria F1414.2 .A15 2002 VIDEO Director: Carlos Henríquez Consalvi. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Film Press Kit Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8b69s3fs No online items Guide to the Film Press Kit Collection Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Film Press Kit PA Mss 39 1 Collection Guide to the Film Press Kit Collection Collection number: PA Mss 39 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Processed by: Staff, Department of Special Collections, Davidson Library Date Completed: 10/21/2011 Encoded by: Zachary Liebhaber © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Film Press Kit collection Dates: 1975-2005 Collection number: PA Mss 39 Creator: University of California, Santa Barbara, Arts and Lectures Collection Size: 9 linear ft.(28 boxes). Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Abstract: Press kits for motion pictures, mostly independent releases, including promotional material, clippings, and advertising materials. Physical location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access The use of the collection is unrestricted. Many of these films were shown by the UCSB Arts and Lectures series. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. -

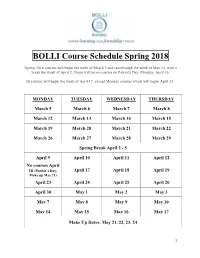

BOLLI Course Schedule Spring 2018

BOLLI Course Schedule Spring 2018 Spring 2018 courses will begin the week of March 5 and run through the week of May 14, with a break the week of April 2. There will be no courses on Patriot's Day, Monday, April 16. 5b courses will begin the week of April 17, except Monday courses which will begin April 23. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY March 5 March 6 March 7 March 8 March 12 March 13 March 14 March 15 March 19 March 20 March 21 March 22 March 26 March 27 March 28 March 29 Spring Break April 2 - 5 April 9 April 10 April 11 April 12 No courses April 16 (Patriot’s Day- April 17 April 18 April 19 Make up May 21) April 23 April 24 April 25 April 26 April 30 May 1 May 2 May 3 May 7 May 8 May 9 May 10 May 14 May 15 May 16 May 17 Make Up Dates: May 21, 22, 23, 24 1 Monday BOLLI Study Groups Spring 2018 Period 1 MUS1-10-Mon1 LIT4-10-Mon1 LIT5-5b-Mon1 SOC5-10-Mon1 9:30 a.m.-10:55 a.m. Beyond Hava Nagila: Whodunit? Murder in Existentialism at the Manipulation: How What is Jewish Ethnic Communities Café Hidden Influences Music? Affect Our Choice of Marilyn Brooks Jennifer Eastman Products, Politicians Sandy Bornstein and Priorities 5 Week Course – April 23 – May 21 Sandy Sherizen Period 2 MUS3-10-Mon2 LIT8-10-Mon2 SOC2-5a-Mon2 WRI1-10-Mon2 11:10 a.m. - 12:35 Why Sing Plays? An Historical Fiction: Childhood In the Writing to Discover: A p.m. -

DVD/VHS Title List

2011 SUBJECT VIDEO & DVD LIST -- LANEY LIBRARY LISTENING & VIEWING CENTER **Recently added titles are in RED African American Studies p.1 Journalism p. 29 Architectural , Engineering, & Construction Technology p. 4 Labor Studies p. 30 Art p. 6 Language and Writing p. 31 Asian / Asian American Studies p.7 Law and Justice p. 32 Biology p. 9 Library and Information Studies p. 34 Business / Economics/Accounting p. 10 Literature p.34 Career Guidance p. 11 Mathematics p. 35 Chemistry p. 13 Mexican / Latin American Studies p. 36 Computer Information Systems p. 13 Music / Dance p. 37 Cosmetology p. 14 Native American/Indigenous Peoples Studies p. 39 Culinary Arts p. 14 Near Eastern Studies p. 40 Drama / Theater / Film p. 15 Philosophy / Religion p. 41 Education p. 19 Photography p. 42 English as a Second Language p. 20 Physical Education/ Sports p. 42 Foreign Languages p. 20 Psychology p. 42 Government /Political Science p. 21 Science / Environment p. 43 Health / Medicine / Nutrition / Safety p. 23 Sociology p. 45 History, General p. 25 Women’s Studies p. 47 History, United States p. 26 **Peralta Board of Trustee Meetings p. 47 AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES cc Africa (parts 1-4) DVD 186 African art: legacy of oppression MVHS 1106 African Haitian dance class: Katherine Dunham technique MVHS 975 cc Africans in America (parts 1-4, plus guide) MVHS 1051 Alex Haley: a conversation with Alex Haley MVHS 778 Alice Walker MVHS 759 All power to the people! The Black Panther Party and beyond MVHS 1154 Almos‘ a man MVHS 153 cc Amistad DVD 201 At the river I stand (civil rights) MVHS 890 sub Banished DVD 239 sub La bataille d‘Alger = The battle of Algiers DVD 140 Beyond the dream VI, a celebration of Black history: blacks in politics, a struggle… MVHS 874 Beyond the dream VII, a celebration of Black history: the vanishing Black male… MVHS 875 cc Bill Moyers Journal: The Reverent Jeremiah Wright Speaks Out DVD 421 Bill Robinson: Mr. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr.