Investigating Small Town Shrinkage in the Clutha District of New Zealand and the Local Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Clutha River

IMAF Water-based recreation on the lower Clutha River Fisheries Environmental Report No. 61 lirllilr' Fisheries Research Division N.Z. Ministry of Agriculture and F¡sheries lssN 01't1-4794 Fisheries Environmental Report No. 61 t^later-based necreation on the I ower Cl utha R'i ver by R. ldhiting Fisheries Research Division N.Z. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Roxbu rgh January I 986 FISHERIES ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTS Th'is report js one of a series of reports jssued by Fisheries Research Dìvjsion on important issues related to environmental matters. They are i ssued under the fol I owi ng cri teri a: (1) They are'informal and should not be cited wjthout the author's perm'issi on. (2) They are for l'imited c'irculatjon, so that persons and organ'isat'ions normal ly rece'ivi ng F'i sheries Research Di vi si on publ'i cat'ions shoul d not expect to receive copies automatically. (3) Copies will be issued in'itjaììy to organ'isations to which the report 'i s d'i rectìy rel evant. (4) Copi es wi I 1 be i ssued to other appropriate organ'isat'ions on request to Fì sherì es Research Dj vi si on, M'inì stry of Agricu'lture and Fisheries, P0 Box 8324, Riccarton, Christchurch. (5) These reports wi'lì be issued where a substant'ial report is required w'ith a time constraint, êg., a submiss'ion for a tnibunal hearing. (6) They will also be issued as interim reports of on-going environmental studies for which year by year orintermìttent reporting is advantageous. -

Natural Character, Riverscape & Visual Amenity Assessments

Natural Character, Riverscape & Visual Amenity Assessments Clutha/Mata-Au Water Quantity Plan Change – Stage 1 Prepared for Otago Regional Council 15 October 2018 Document Quality Assurance Bibliographic reference for citation: Boffa Miskell Limited 2018. Natural Character, Riverscape & Visual Amenity Assessments: Clutha/Mata-Au Water Quantity Plan Change- Stage 1. Report prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited for Otago Regional Council. Prepared by: Bron Faulkner Senior Principal/ Landscape Architect Boffa Miskell Limited Sue McManaway Landscape Architect Landwriters Reviewed by: Yvonne Pfluger Senior Principal / Landscape Planner Boffa Miskell Limited Status: Final Revision / version: B Issue date: 15 October 2018 Use and Reliance This report has been prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Boffa Miskell does not accept any liability or responsibility in relation to the use of this report contrary to the above, or to any person other than the Client. Any use or reliance by a third party is at that party's own risk. Where information has been supplied by the Client or obtained from other external sources, it has been assumed that it is accurate, without independent verification, unless otherwise indicated. No liability or responsibility is accepted by Boffa Miskell Limited for any errors or omissions to the extent that they arise from inaccurate information provided by the Client or -

General Distribution and Characteristics of Active Faults and Folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City Districts, Otago

General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City districts, Otago DJA Barrell GNS Science Consultancy Report 2020/88 April 2021 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to Otago Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of or reliance on any contents of this report by any person other than Otago Regional Council and shall not be liable to any person other than Otago Regional Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: March 2021 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Barrell DJA. 2021. General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Clutha and Dunedin City districts, Otago. Dunedin (NZ): GNS Science. 71 p. Consultancy Report 2020/88. Project Number 900W4088 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... IV 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .....................................................................................................1 1.2 Scope and Purpose .........................................................................................5 2.0 INFORMATION SOURCES ........................................................................................7 -

Otago Mar 2018

Birds New Zealand PO Box 834, Nelson. osnz.org.nz Regional Representative: Mary Thompson 197 Balmacewen Rd, Dunedin. [email protected] 03 4640787 Regional Recorder: Richard Schofield, 64 Frances Street, Balclutha 9230. [email protected] Otago Region Newsletter 3/2018 March 2018 Otago Summer Wader Count 27 November 2017 Catlins Karitane Karitane Aramoana Aramoana Total 2017 Total 2017 Total 2016 Blueskin Bay Blueskin Bay Harbour east east Harbour Papanui Inlet Papanui Inlet Harbour west west Harbour Inlet Hoopers Pied Oystercatcher 57 129 0 195 24 60 21 238 724 270 Variable Oystercatcher 14 12 0 26 34 47 0 4 137 45 Pied Stilt 26 160041515 6 8297 Banded Dotterel 9 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 15 43 Spur-winged Plover 12 1 2 3 4 50 7 16 95 30 Bar-tailed Godwit 124 472 58 0 0 8 1050 305 2017 1723 I was told that the predicted high tide of 1.8metres was much lower. There were no waders at Aramoana and large areas of mud flats at Hoopers Inlet were occupied by feeding birds; all rather difficult to count accurately. But the results was very good with all areas surveyed by plenty of counters. Many thanks to all for this very good wader count. Peter Schweigman Better late than never. Apologies ed. 2 Ornithological snippets 5 Chukor were seen & photographed at Ben Lomond on 5th March by Trevor Sleight. A pair of Indian Peafowl of unknown origin put in an appearance near Lake Waihola on 15th March. A moulting Erect-crested Penguin was seen at Jacks Bay (Catlins) on 18th Feb, while another crested penguin was at Anderson’s Lagoon (Palmerston) by Paul Smaill on 2nd March. -

Prospectus.2021

2021 PROSPECTUS Contents Explanation 1 Tuia Overview 2 Rangatahi Selection 3 Selection Process 4 Mayoral/Mentor and Rangatahi Expectations 6 Community Contribution 7 Examples 8 Rangatahi Stories 9 Bronson’s story 9 Maui’s story 11 Puawai’s story 12 Tuia Timeframes 14 Key Contacts 15 Participating Mayors 2011-2020 16 Explanation Tōia mai ngā tāonga a ngā mātua tīpuna. Tuia i runga, tuia i raro, tuia i roto, tuia i waho, tuia te here tāngata. Ka rongo te pō, ka rongo te ao. Tuia ngā rangatahi puta noa i te motu kia pupū ake te mana Māori. Ko te kotahitanga te waka e kawe nei te oranga mō ngā whānau, mō ngā hapū, mō ngā iwi. Poipoia te rangatahi, ka puta, ka ora. The name ‘Tuia’ is derived from a tauparapara (Māori proverbial saying) that is hundreds of years old. This saying recognises and explains the potential that lies within meaningful connections to: the past, present and future; to self; and to people, place and environment. The word ‘Tuia’ means to weave and when people are woven together well, their collective contribution has a greater positive impact on community. We as a rangatahi (youth) leadership programme look to embody this by connecting young Māori from across Aotearoa/New Zealand - connecting passions, aspirations and dreams of rangatahi to serve our communities well. 1 Tuia Overview Tuia is an intentional, long-term, intergenerational approach to develop and enhance the way in which rangatahi Māori contribute to communities throughout New Zealand. We look to build a network for rangatahi to help support them in their contribution to their communities. -

In Liquidation)

Liquidators’ First Report on the State of Affairs of Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 8 March 2019 Contents Introduction 2 Statement of Affairs 4 Creditors 5 Proposals for Conducting the Liquidation 6 Creditors' Meeting 7 Estimated Date of Completion of Liquidation 8 Appendix A – Statement of Affairs 9 Appendix B – Schedule of known creditors 10 Appendix C – Creditor Claim Form 38 Appendix D - DIRRI 40 Liquidators First Report Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 1 Introduction David Ian Ruscoe and Malcolm Russell Moore, of Grant Thornton New Zealand Limited (Grant Thornton), were appointed joint and several Interim Liquidators of the Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) (the “Trust” or “Taratahi”) by the High Count in Wellington on 19 December 2018. Mr Ruscoe and Mr Moore were then appointed Liquidators of the Trust on 5th February 2019 at 10.50am by Order of the High Court. The Liquidators and Grant Thornton are independent of the Trust. The Liquidators’ Declaration of Independence, Relevant Relationships and Indemnities (“DIRRI”) is attached to this report as Appendix D. The Liquidators set out below our first report on the state of the affairs of the Companies as required by section 255(2)(c)(ii)(A) of the Companies Act 1993 (the “Act”). Restrictions This report has been prepared by us in accordance with and for the purpose of section 255 of the Act. It is prepared for the sole purpose of reporting on the state of affairs with respect to the Trust in liquidation and the conduct of the liquidation. -

Annual Water Quality Monitoring Summary Clutha River 2007-2008

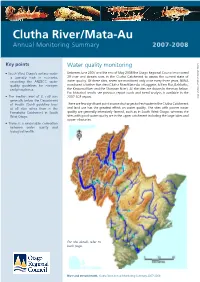

Clutha River/Mata-Au Annual Monitoring Summary 2007-2008 Key points Water quality monitoring • South West Otago’s surface water Between June 2007 and the end of May 2008 the Otago Regional Council monitored is typically high in nutrients, 29 river and stream sites in the Clutha Catchment to assess the current state of exceeding the ANZECC water water quality. Of these sites, seven are monitored only once every three years. NIWA quality guidelines for nitrogen monitored a further five sites (Clutha River/Mata-Au at Luggate, Millers Flat, Balclutha, and phosphorus. the Kawarau River and the Shotover River). All the sites are shown in the map below. For historical results see previous report cards and trend analysis is available in the • The median level of E. coli was 2007 SOE report. Cover photos courtesy of Stephen Moore generally below the Department of Health (DoH) guideline level There are few significant point source discharges to freshwater in the Clutha Catchment at all sites other than in the and land use has the greatest effect on water quality. The sites with poorer water Pomahaka Catchment in South quality are generally intensively farmed, such as in South West Otago, whereas the West Otago. sites with good water quality are in the upper catchment including the large lakes and upper tributaries. • There is a reasonable correlation between water quality and biological health. For site details refer to back page. River and stream health, Clutha River Annual Monitoring Summary 2007-2008 Water quality results Guidelines & standards -

1274 the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

1274 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 38 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 267348 Robertson, Alexander Fraser, railway employee, Tahakopa, 376237 Shanks, John (jun.), farm-manager, Warepa, South Otago. South Otago. 060929 Shanks, Stuart, farm hand, Waikana, Ferndale Rural 281491 Robertson, Alexander William, shepherd, "Warwick Delivery, Gore. Downs," Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. 397282 Sharp, Charles, farmer, Tuapeka Mouth. 257886 Robertson, Alfred Roy, labourer, 152 Spay St., Invercargill. 426037 Shaw, Ivan Holden, paper-mill employee, Oakland St., 203202 Robertson, Douglas Belgium, labourer, Roxburgh. Mataura. 262523 Robertson, Eric James, farmer, Heddon Bush Rural Deli very, 282484 Shaw, John, N.Z.R. employee, care of New Zealand Railways, Winton. Milton, South Otago. 151974 Robertson, Francis William, Ellis Rd., care of Public 421302 Shaw, William Martin, farm hand, Orepuki. W arks, W aikiwi, Invercargill. 066560 Shearer, George, quarryman, care of G. Hawkins, \Vinton. 097491 Robertson, James Ian, wool-sorter, Awarua Plains Post 116926 Sheat, Robert Davy, teamster, Moneymore Rural Delivery, office, Southland. Milton. 423543 Robertson, Menzie Athol, labourer, Woodend, Southland.- 253436 Shedden, Allen Miller, coal-trucker, Nightcaps. 298971 Robertson, Robert Alexander, dairy-farmer, Wright's Bush 252526 Sheddan, Maurice, farm labourer, Gore, \Vail,aka Rural Gladfield Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Delivery. 294830 Robertson, Struan Malcolm, labourer, Awarua Plains, 283883 Sheddan, Robert Bruce, farm hand, Scott's Gap, Otautau Southland. Rural Delivery. 431165 Robertson, Tasman Harrie, labourer, 215 Bowmont St., 010254 Sheehan, Walter, general labourer, Te Tipua Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Gore. 247092 Robertson, William Douglas, fisherman, Half-moon Bay, 280428 Sheehan, Walter James, farm hand, Te Tua, Riverton Rural Stewart Island. -

Anglers' Notice for Fish and Game Region Conservation

ANGLERS’ NOTICE FOR FISH AND GAME REGION CONSERVATION ACT 1987 FRESHWATER FISHERIES REGULATIONS 1983 Pursuant to section 26R(3) of the Conservation Act 1987, the Minister of Conservation approves the following Anglers’ Notice, subject to the First and Second Schedules of this Notice, for the following Fish and Game Region: Otago NOTICE This Notice shall come into force on the 1st day of October 2017. 1. APPLICATION OF THIS NOTICE 1.1 This Anglers’ Notice sets out the conditions under which a current licence holder may fish for sports fish in the area to which the notice relates, being conditions relating to— a.) the size and limit bag for any species of sports fish: b.) any open or closed season in any specified waters in the area, and the sports fish in respect of which they are open or closed: c.) any requirements, restrictions, or prohibitions on fishing tackle, methods, or the use of any gear, equipment, or device: d.) the hours of fishing: e.) the handling, treatment, or disposal of any sports fish. 1.2 This Anglers’ Notice applies to sports fish which include species of trout, salmon and also perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only). 1.3 Perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only) are also classed as coarse fish in this Notice. 1.4 Within coarse fishing waters (as defined in this Notice) special provisions enable the use of coarse fishing methods that would otherwise be prohibited. 1.5 Outside of coarse fishing waters a current licence holder may fish for coarse fish wherever sports fishing is permitted, subject to the general provisions in this Notice that apply for that region. -

NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority

No. 11 267 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 24 FEBRUARY 1966 CORRIGENDUM the land described in the Schedule hereto shall, upon the publication hereof in the Gazette, become road, and that :the said road shall be under the control of the Oroua County IN the Order in Council dated the 15th day of December Council and shall be maintained by the said Council in like 1965, and published in Gazette No. 3, 27 January 1966, page manner as other public highways are controlled and main 79, consenting to the raising of loans by certain local authori tained by the said Council. ties, in the amount of the loan to be raised by the Mount Roskill Borough Council, for the figure "£35,000" read "£35,500", which last-mentioned figure appears in the Order in Council signed by His Excellency the Governor-General in SCHEDULE Council. WELLINGTON LAND DISTRICT Dated at Wellington this 18th day of February 1966. APPROXIMATE area of the piece of land: N. V. LOUGH, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury. A. R. P. Being 0 2 39·7 Portion of railway land in Proclamation No. 31526. Situated in Block V, Oroua Survey District, Oroua County (S.O. 26317). Allocating Land Taken for a Railway to the Purposes of As the same is more particularly delineated on the plan Street at Huntly marked L.O. 20552 deposited in the office of the Minister of Railways at Wellington, and thereon coloured blue. BERNARD FERGUSSON, Governor-General Given under the hand of His Excellency rthe Governor General, and issued under the Seal of New Zealand, this A PROCLAMATION 18th day of February 1966. -

Waste for Otago (The Omnibus Plan Change)

Key Issues Report Plan Change 8 to the Regional Plan: Water for Otago and Plan Change 1 to the Regional Plan: Waste for Otago (The Omnibus Plan Change) Appendices Appendix A: Minster’s direction matter to be called in to the environment court Appendix B: Letter from EPA commissioning the report Appendix C: Minister’s letter in response to the Skelton report Appendix D: Skelton report Appendix E: ORC’s letter in responding to the Minister with work programme Appendix F: Relevant sections of the Regional Plan: Water for Otago Appendix G: Relevant sections of the Regional Plan: Waste for Otago Appendix H: Relevant provisions of the Resource Management Act 1991 Appendix I: National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 Appendix J: Relevant provisions of the National Environmental Standards for Freshwater 2020 Appendix K: Relevant provisions of the Resource Management (Stock Exclusion) Regulations 2020 Appendix L: Relevant provisions of Otago Regional Council Plans and Regional Policy Statements Appendix M: Relevant provisions of Iwi management plans APPENDIX A Ministerial direction to refer the Otago Regional Council’s proposed Omnibus Plan Change to its Regional Plans to the Environment Court Having had regard to all the relevant factors, I consider that the matters requested to be called in by Otago Regional Council (ORC), being the proposed Omnibus Plan Change (comprised of Water Plan Change 8 – Discharge Management, and Waste Plan Change 1 – Dust Suppressants and Landfills) to its relevant regional plans are part of a proposal of national significance. Under section 142(2) of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), I direct those matters to be referred to the Environment Court for decision. -

Closing Legal Submissions for the NZ Transport Agency and Porirua City Council

Before a Board of Inquiry Transmission Gully Notices of Requirement and Consents under: the Resource Management Act 1991 in the matter of: Notices of requirement for designations and resource consent applications by the NZ Transport Agency, Porirua City Council and Transpower New Zealand Limited for the Transmission Gully Proposal between: NZ Transport Agency Requiring Authority and Applicant and: Porirua City Council Local Authority and Applicant and: Transpower New Zealand Limited Applicant Closing legal submissions for the NZ Transport Agency and Porirua City Council Dated: 14 March 2012 REFERENCE: John Hassan ([email protected]) Nicky McIndoe ([email protected]) 1 CONTENTS CLOSING LEGAL SUBMISSIONS FOR THE NZ TRANSPORT AGENCY AND PORIRUA CITY COUNCIL 4 INTRODUCTION 4 The narrowing of issues to certain conditions and controls 4 Regional resource consents 4 Notices of Requirement 4 Overarching questions 4 Structure of closing submissions 5 Regional consents 6 Noise mitigation and conditions in the NoRs 6 Other issues as to resource consent and Notice of Requirement conditions 6 Other matters 6 WHAT THE PRECAUTIONARY APPROACH REQUIRES TO ADDRESS ECOLOGICAL RISKS FROM SEDIMENT 7 Reliability of sediment yield and effects modelling and assessment 7 Reliability of harbour modelling and effects‟ assessment 10 Are the effects on the Inlet acceptable? 12 Why Dr De Luca‟s opinion should be preferred 13 Controls and conditions are appropriately conservative 15 The sediment management controls 15 The sediment management