Studies on Auranofin and Aurothioglucose in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

Injectable Medication Hcpcs/Dofr Crosswalk

INJECTABLE MEDICATION HCPCS/DOFR CROSSWALK HCPCS DRUG NAME GENERIC NAME PRIMARY CATEGORY SECONDARY CATEGORY J0287 ABELCET Amphotericin B lipid complex THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J0400 ABILIFY Aripiprazole, intramuscular, 0.25 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ J0401 ABILIFY MAINTENA Apriprazole 300mg, IM injection THERAPEUTIC INJ J9264 ABRAXANE paclitaxel protein-bound particles, 1 mg J1120 ACETAZOLAMIDE SODIUM Acetazolamide sodium injection THERAPEUTIC INJ J0132 ACETYLCYSTEINE INJ Acetylcysteine injection, 10 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ ACTEMRA 162mg/0.9ml Syringe (50242- J3262 SELF-INJECTABLE 0138-01) Tocilizumab, 1 mg ACTEMRA INJECTION (50242-0136-01, J3262 50242-0137-01) Tocilizumab 200mg, 400mg THERAPEUTIC INJ J0800 ACTHAR HP Corticotropin injection THERAPEUTIC INJ Hemophilus influenza b vaccine (Hib), PRP-T conjugate (4- 90648 ACTHIB dose schedule), for intramuscular use THERAPEUTIC INJ IMMUNIZATIONS J0795 ACTHREL Corticorelin ovine triflutal THERAPEUTIC INJ J9216 ACTIMMUNE Interferon gamma 1-b 3 miillion units SELF-INJECTABLE CHEMO ADJUNCT* J2997 ACTIVASE Alteplase recombinant, 1mg THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J0133 ACYCLOVIR SODIUM Acyclovir, 5 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** 90715 ADACEL Tdap vaccine, > 7 yrs, IM THERAPEUTIC INJ IMMUNIZATIONS J2504 ADAGEN Pegademase bovine, 25 IU THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J9042 ADCETRIS Brentuximab vedotin Injection THERAPEUTIC INJ CHEMOTHERAPY J0153 ADENOCARD Adenosine 6 MG THERAPEUTIC INJ J0171 ADRENALIN Adrenalin (epinephrine) inject THERAPEUTIC INJ J9000 ADRIAMYCIN Doxorubicin -

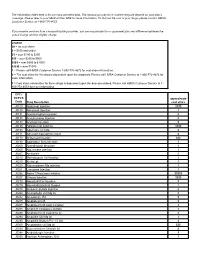

CPT / HCPCS Code Drug Description Approximate Cost Share

The information listed here is for our most prevalent plan. The amount you pay for a covered drug will depend on your plan’s coverage. Please refer to your Medical Plan GTB for more information. To find out the cost of your drugs, please contact HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-776-4672. If you receive services from a nonparticipating provider, you are responsible for a copayment plus any difference between the actual charge and the eligible charge. Legend $0 = no cost share $ = $100 and under $$ = over $100 to $250 $$$ = over $250 to $500 $$$$ = over $500 to $1000 $$$$$ = over $1000 1 = Please call HMSA Customer Service 1-800-776-4672 for cost share information. 2 = The cost share for this drug is dependent upon the diagnosis. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-772-4672 for more information. 3 = Cost share information for these drugs is dependent upon the dose prescribed. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1- 800-772-4672 for more information. CPT / HCPCS approximate Code Drug Description cost share J0129 Abatacept Injection $$$$ J0130 Abciximab Injection 3 J0131 Acetaminophen Injection $ J0132 Acetylcysteine Injection $ J0133 Acyclovir Injection $ J0135 Adalimumab Injection $$$$ J0153 Adenosine Inj 1Mg $ J0171 Adrenalin Epinephrine Inject $ J0178 Aflibercept Injection $$$ J0180 Agalsidase Beta Injection 3 J0200 Alatrofloxacin Mesylate 3 J0205 Alglucerase Injection 3 J0207 Amifostine 3 J0210 Methyldopate Hcl Injection 3 J0215 Alefacept 3 J0220 Alglucosidase Alfa Injection 3 J0221 Lumizyme Injection 3 J0256 Alpha 1 Proteinase Inhibitor -

Canine Pemphigus Vulgaris Treated with Gold Salt Therapy

CASE REPORT Canine Pemphigus Vulgaris Treated with Gold Salt Therapy G.P. OLYNYK AND B.J. GUTHRIE Edgemont Veterinary Clinic, #12, 34 Edgedale Drive North West, Calgary, Alberta T3A 2R4 Summary treated with antibiotics, prednisone, euthanasia, gold salt therapy, or A nine year old spayed female Collie vitamins and metronidazole with no further antibiotic-corticosteroid treat- was diagnosed as having pemphigus lasting or dramatic improvement. The ments with the owner. vulgaris. Response to corticosteroid dog had previously been diagnosed as On May 13, 1982 we initiated auro- and antibiotic therapies was unsatis- having hip dysplasia and secondary thioglucose3 therapy as outlined pre- factory. Aurothioglucose therapy was arthritis. viously (1). Two intramuscular injec- used later as the sole treatment. The tions of 5.0 and 10.0 mg were given as dog achieved a complete remission Clinical Findings and Treatment tests of tolerance on May 13 and 20 lasting at least ten months. At first presentation, the physical respectively. The therapeutic series examination was unremarkable with involved six weekly intramuscular Resumme' the exception of skin lesions. The injections at 1.0 mg/kg. These injec- Traitement du pemphigus vulgaire refractory nature and the location and tions were given May 27, June 3, 10, canin avec de l'aurothioglucose nature of the lesions suggested a diag- 17, 24 and 30. No other therapy was Les auteurs ont diagnostique la nosis of pemphigus vulgaris. used. A physical examination, weigh- pemphigus vulgaire, chez une chienne A biopsy was obtained; the resulting in and discussion with the owner Collie castree et agee de neuf ans. -

Cumulative Cross Index to Iarc Monographs

PERSONAL HABITS AND INDOOR COMBUSTIONS volume 100 e A review of humAn cArcinogens This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, which met in Lyon, 29 September-6 October 2009 LYON, FRANCE - 2012 iArc monogrAphs on the evAluAtion of cArcinogenic risks to humAns CUMULATIVE CROSS INDEX TO IARC MONOGRAPHS The volume, page and year of publication are given. References to corrigenda are given in parentheses. A A-α-C .............................................................40, 245 (1986); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Acenaphthene ........................................................................92, 35 (2010) Acepyrene ............................................................................92, 35 (2010) Acetaldehyde ........................36, 101 (1985) (corr. 42, 263); Suppl. 7, 77 (1987); 71, 319 (1999) Acetaldehyde associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages ..............100E, 377 (2012) Acetaldehyde formylmethylhydrazone (see Gyromitrin) Acetamide .................................... 7, 197 (1974); Suppl. 7, 56, 389 (1987); 71, 1211 (1999) Acetaminophen (see Paracetamol) Aciclovir ..............................................................................76, 47 (2000) Acid mists (see Sulfuric acid and other strong inorganic acids, occupational exposures to mists and vapours from) Acridine orange ...................................................16, 145 (1978); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Acriflavinium chloride ..............................................13, -

Channeling to Treatment and Associated Changes in Disease Activity Over 12 Months in Patients with RA Treated with Abatacept

553 Scientific Content On-demand Channeling to Treatment and Associated Changes in Disease Activity Over 12 Months in Patients To receive a copy of this poster With RA Treated With Abatacept Versus Other DMARDs in Real-World Community Practice Settings OR Text RWE to Scan QR code via a 1 2 1 1 1 1 3 1 +1-609-917-7119 barcode reader application L Ferri, JR Curtis, E Alemao, J Bryson, K Lozenski, S Balachandar, V Rajagopalan, Y Bao By requesting this content, you agree to receive a one-time communication using automated technology. Messaging & data rates may apply. Links are valid for 30 days after the congress presentation date. 1 2 3 Copies of this poster obtained through Quick Response (QR) code Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA; University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA; Mu Sigma, Bangalore, India or text message are for personal use only and may not be reproduced without permission from ACR and the authors of this poster. Mean changes from baseline to Year 1 in CDAI scores were assessed using Introduction Figure 1. Study Design Table 2. Changes in CDAI Over 12 Months in Patients With RA*,† multivariate linear regressions adjusting for baseline covariates, including age, Abatacept, a selective T-cell co-stimulatory modulator, has shown efficacy sex, smoking status, BMI, Charlson Comorbidity Index, CDAI score and number Change from Difference in Window for measuring Baseline, Year 1, 1 n baseline, change, p value similar to TNF inhibitors (TNFi) for RA management in clinical trial settings. Baseline period follow-up disease LSM (95% CI)‡ LSM (95% CI)‡ of prior treatments (b/tsDMARDs, TNFi and cDMARDs). -

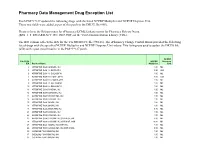

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List Patch PSS*1*127 updated the following drugs with the listed NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit. These two fields were added as part of this patch to the DRUG file (#50). Please refer to the Release notes for ePharmacy/ECME Enhancements for Pharmacy Release Notes (BPS_1_5_EPHARMACY_RN_0907.PDF) on the VistA Documentation Library (VDL). The IEN column reflects the IEN for the VA PRODUCT file (#50.68). The ePharmacy Change Control Board provided the following list of drugs with the specified NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit values. This listing was used to update the DRUG file (#50) with a post install routine in the PSS*1*127 patch. NCPDP File 50.68 NCPDP Dispense IEN Product Name Multiplier Unit 2 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 3 ATROPINE SO4 1% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 6 ATROPINE SO4 1% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 7 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 8 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 9 ATROPINE SO4 3% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 10 ATROPINE SO4 2% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 11 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 12 ATROPINE SO4 0.05MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 13 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/0.5ML INJ 1.00 ML 14 ATROPINE SO4 0.5MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 15 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 16 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 18 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/0.7ML INJ 0.70 ML 21 ATROPINE SO4 0.3MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 22 ATROPINE SO4 0.8MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 23 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,5ML 5.00 ML 24 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,10ML 10.00 ML 25 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ,AMP,1ML 1.00 ML 26 ATROPINE SO4 0.2MG/0.5ML INJ,AMP,0.5ML 0.50 ML 30 CODEINE PO4 30MG/ML -

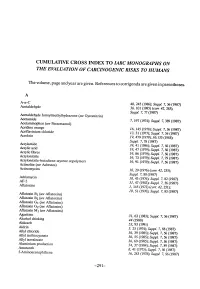

Cumulative Index to the Monographs Series

eUMULATIV eROSS INDEX TO IARC MONOGRAHS ON THE EVALUATION OF CARCINOGENIC RlSKS TO HUMANS The volume, page and year are given. References to corrigenda are given in parentheses. A A-a-C 40, 245 (1986); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Acetaldehyde 36, 101 (1985) (corr 42, 263); Suppl. 7, 77 (1987) Acetaldehyde formylmethylhydrazone (see Gyromitrin) Acetamide 7, 197 (1974); Suppl. 7, 389 (1987) Acetaminophen (see Paracetamol) Acridine orange 16, 145 (1978); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Acriaviium chloride 13,31 (1977); Suppl. 7,56 (1987) Acrolein 19, 479 (1979); 36,133 (1985); Suppl, 7, 78 (1987) Aciylamide 39,41 (1986); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Acrylic acid 19,47 (1979); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Acrylìc fibres 19,86 (1979); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Acrylonitrie 19, 73 (1979); Suppl. 7, 79 (1987) Acrylonitrie-butadiene-styrene copolymers 19,91 (1979); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Actinolite (see Asbestos) Actinomycins JO, 29 (1976) (COrT 42, 255); Suppl. 7, 80 (1987) Adrimycin 10, 43 (1976l' Suppl. 7,82 (1987) AF-2 31,47 (1983); Suppl. 7,56(1987) Afatoxins 1, 145 (1972) (COrT 42,251); JO, 51 (1976); Suppl. 7, 83 (1987) Afatoxin Bi (see Afatoxins) Afatoxi Bi (see Afatoxins) Afatoxin Gi (see Afatoxins) Afatoxin Gi (see Afatoxins) Afatoxin Mi (see Afatoxins) Agaritine 31, 63 (1983); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Alcohol drinking 44 (1988) Aldicarb 53, 93 (1991) Aldrin 5, 25 (1974); Suppl. 7, 88 (1987) Allyl chloride 36, 39 (1985); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Allyl isothiocyanate 36, 55 (1985); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Allyl isovalerate 36, 69 (1985); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Aluminium production 34, 37 (1984); Suppl. -

A Case of Pemphigus Vulgaris Improved by Cigarette Smoking

THE CUTTING EDGE SECTION EDITOR: GEORGE J. HRUZA, MD; ASSISTANT SECTION EDITORS: LYNN A. CORNELIUS, MD; JON STARR, MD A Case of Pemphigus Vulgaris Improved by Cigarette Smoking Jessica N. Mehta, MD; Ann G. Martin, MD; Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Mo The Cutting Edge: Challenges in Medical and Surgical Therapeutics ported that he stopped smoking at the time of disease ex- Editorial Comment: An inverse relationship be- acerbation. When his disease flared again, he was treated tween cigarette smoking and the activity of cer- with intramuscular injections of aurothioglucose (75 mg tain diseases, most notably ulcerative colitis, has weekly), without improvement. been recognized. Similarly, nicotine patches have Examination revealed a 4 3 4-cm erosive plaque with been used in the treatment of pyoderma gangreno- yellow crusting on the patient’s right cheek and a 2 3 2- sum. Although the exact mechanism of the “ben- cm area of erosion on his left cheek (Figure 1, left). A eficial” effect of smoking and/or nicotine on the ac- punch biopsy specimen from the lesion on the right cheek tivity of these diseases has not been definitively demonstrated an epidermis with a split that extended to elucidated, nicotine has been found to affect the adnexal structures, as well as mild acute and chronic in- production of certain proinflammatory cyto- flammation in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Indi- kines. rect immunoflorescence was positive for epidermal an- As physicians, we must not forget the posi- tibodies at a titer of 1:240. tive association of smoking with lung carcinoma The dosage of prednisone was increased to 80 mg/d, and cardiac and peripheral vascular disease, as well and cyclophosphamide was added to the regimen at a dos- as with impaired wound healing; therefore, im- age of 25 mg/d. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of - Medicines belonging to the ATC group M01 (Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 6 DISCLAIMER 8 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 9 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Phenylbutazone (ATC: M01AA01) 11 Mofebutazone (ATC: M01AA02) 17 Oxyphenbutazone (ATC: M01AA03) 18 Clofezone (ATC: M01AA05) 19 Kebuzone (ATC: M01AA06) 20 Indometacin (ATC: M01AB01) 21 Sulindac (ATC: M01AB02) 25 Tolmetin (ATC: M01AB03) 30 Zomepirac (ATC: M01AB04) 33 Diclofenac (ATC: M01AB05) 34 Alclofenac (ATC: M01AB06) 39 Bumadizone (ATC: M01AB07) 40 Etodolac (ATC: M01AB08) 41 Lonazolac (ATC: M01AB09) 45 Fentiazac (ATC: M01AB10) 46 Acemetacin (ATC: M01AB11) 48 Difenpiramide (ATC: M01AB12) 53 Oxametacin (ATC: M01AB13) 54 Proglumetacin (ATC: M01AB14) 55 Ketorolac (ATC: M01AB15) 57 Aceclofenac (ATC: M01AB16) 63 Bufexamac (ATC: M01AB17) 67 2 Indometacin, Combinations (ATC: M01AB51) 68 Diclofenac, Combinations (ATC: M01AB55) 69 Piroxicam (ATC: M01AC01) 73 Tenoxicam (ATC: M01AC02) 77 Droxicam (ATC: M01AC04) 82 Lornoxicam (ATC: M01AC05) 83 Meloxicam (ATC: M01AC06) 87 Meloxicam, Combinations (ATC: M01AC56) 91 Ibuprofen (ATC: M01AE01) 92 Naproxen (ATC: M01AE02) 98 Ketoprofen (ATC: M01AE03) 104 Fenoprofen (ATC: M01AE04) 109 Fenbufen (ATC: M01AE05) 112 Benoxaprofen (ATC: M01AE06) 113 Suprofen (ATC: M01AE07) 114 Pirprofen (ATC: M01AE08) 115 Flurbiprofen (ATC: M01AE09) 116 Indoprofen (ATC: M01AE10) 120 Tiaprofenic Acid (ATC: -

STUDY PROTOCOL Title Evaluation of Xeljanz Access Barriers Via

Xeljanz (tofacitinib) A3921346 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Amendment 1 Final, October 7, 2019 NON-INTERVENTIONAL (NI) STUDY PROTOCOL Title Evaluation of Xeljanz Access Barriers via Patient OOP Costs and TNFi cycling Protocol number Pfizer protocol ID A3921346 Protocol version identifier Version number 1.1 Date October 7, 2019 Active substance L04AA29 (tofacitinib) Medicinal product Xeljanz (tofacitinib) Page 1 Xeljanz (tofacitinib) A3921346 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Amendment 1 Final, October 7, 2019 Research question and objectives Primary Objectives: To evaluate the impact of (1a) Xeljanz index prescription OOP costs and (1b) TNFi cycling with etanercept and adalimumab vs. switching to Xeljanz on treatment persistence. Secondary Objectives: 2) To compare (1) high vs. low Xeljanz index prescription OOP costs, and, (2) TNFi cycling (2 groups) with etanercept and adalimumab vs. switching to Xeljanz (2 groups) on: • Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. • Treatment patterns including dosing, concomitant medication use, adherence, switching and a 6- factor effectiveness proxy measure (Curtis algorithm) between comparator cohorts. • Post-index and change (Post-Pre) in All-cause and RA-related health care utilization associated costs. CCI Page 2 Xeljanz (tofacitinib) A3921346 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Amendment 1 Final, October 7, 2019 Author PPD , PharmD,MS PPD ,PPD PHI, Pfizer Inc. Page 3 Xeljanz (tofacitinib) A3921346 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Amendment 1 Final, October 7, 2019 1. TABLE OF -

2019 Table of Drugs

2019 Table of Drugs Questions regarding coding and billing guidance should be submitted to the insurer in whose jurisdiction a claim would be filed. For private sector health insurance systems, please contact the individual private insurance entity. For Medicaid systems, please contact the Medicaid Agency in the state in which the claim is being filed. For Medicare, contact the Medicare contractor. IA - Intra-arterial administration IV - Intravenous administration IM - Intramuscular administration IT - Intrathecal SC - Subcutaneous administration INH - Administration by inhaled solution VAR - Various routes of administration OTH - Other routes of administration ORAL - Administered orally Intravenous administration includes all methods, such as gravity infusion, injections, and timed pushes. The ‘VAR’ posting denotes various routes of administration and is used for drugs that are commonly administered into joints, cavities, tissues, or topical applications, in addition to other parenteral administrations. Listings posted with ‘OTH’ indicate other administration methods, such as suppositories or catheter injections. A Abatacept 10 mg IV J0129 Abbokinase, see Urokinase Abbokinase, Open Cath, see Urokinase Abciximab 10 mg IV J0130 Abelcet, see Amphotericin B Lipid Complex ABLC, see Amphotericin B AbobotulinumtoxintypeA 5 units IM J0586 Acetaminophen 10 mg IV J0131 Acetazolamide sodium up to 500 mg IM, IV J1120 Acetylcysteine, IVection 100 mg IV J0132 Acetylcysteine, unit dose form per gram INH J7604, J7608 1 Achromycin, see Tetracycline Actemra,