San Francisco's Haymarket: a Redemptive Tale of Class Struggle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

The Communist Manifesto (Get Political)

The Communist Manifesto Marx & Engels 00 pre i 2/7/08 19:38:10 <:IEA>I>86A www.plutobooks.com Revolution, Black Skin, Democracy, White Masks Socialism Frantz Fanon Selected Writings Forewords by V.I. Lenin Homi K. Edited by Bhabha and Paul Le Blanc Ziauddin Sardar 9780745328485 9780745327600 Jewish History, The Jewish Religion Communist The Weight Manifesto of Three Karl Marx and Thousand Years Friedrich Engels Israel Shahak Introduction by Forewords by David Harvey Pappe / Mezvinsky/ 9780745328461 Said / Vidal 9780745328409 Theatre of Catching the Oppressed History on Augusto Boal the Wing 9780745328386 Race, Culture and Globalisation A. Sivanandan Foreword by Colin Prescod 9780745328348 Marx & Engels 00 pre ii 2/7/08 19:38:10 theth communist manifesto KARL MARX and FRIEDRICH ENGELS With an introduction by David Harvey PLUTO PRESS www.plutobooks.com Marx & Engels 00 pre iii 2/7/08 19:38:10 The Manifesto of the Communist Party was fi rst published in February 1848. English translation by Samuel Moore in cooperation with Friedrich Engels, 1888. This edition fi rst published 2008 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com The full text of the manifesto, along with the endnotes and prefaces to various language editions, has been taken from the Marx/Engels Internet Archive (marxists.org) Transcription/Markup: Zodiac and Brian Basgen, 1991, 2000, 2002 Proofread: Checked and corrected against the English Edition of 1888, by Andy Blunden, 2004. The manifesto and the appendix as published here is public domain. Introduction copyright © David Harvey 2008 The right of David Harvey as author of the Introduction has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Refugees As Surplus Population: Race, Migration and Capitalist Value Regimes

New Political Economy ISSN: 1356-3467 (Print) 1469-9923 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnpe20 Refugees as Surplus Population: Race, Migration and Capitalist Value Regimes Prem Kumar Rajaram To cite this article: Prem Kumar Rajaram (2018) Refugees as Surplus Population: Race, Migration and Capitalist Value Regimes, New Political Economy, 23:5, 627-639, DOI: 10.1080/13563467.2017.1417372 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1417372 Published online: 05 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 610 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cnpe20 NEW POLITICAL ECONOMY 2018, VOL. 23, NO. 5, 627–639 https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1417372 Refugees as Surplus Population: Race, Migration and Capitalist Value Regimes Prem Kumar Rajaram Department of Sociology & Social Anthropology, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Refugees and migrants are often studied as though they have no Received 21 November 2017 relation to the racial and class structures of the societies in which they Accepted 5 December 2017 reside. They are strangers to be governed by ‘integration’ policy and KEYWORDS border management. Refugees and migrants are, however, subjects of Refugees; surplus contemporary capitalism struggling to render themselves valuable populations; colonialism; capitalist modes of production. I study the government of refugees and Marx; Foucault migrants in order to examine capitalist value regimes. Societal values and hierarchies reflected in capitalist modes of production impact on struggles of racialised subaltern groups to translate body power into valued labour. -

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

Spatial Practices of Icarian Communism

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-25 Spatial Practices of Icarian Communism John Derek McCorquindale Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, and the Italian Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McCorquindale, John Derek, "Spatial Practices of Icarian Communism" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1364. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A SPATIAL HISTORY OF ICARIAN COMMUNISM by John Derek McCorquindale A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of French & Italian Brigham Young University April 2008 ABSTRACT A SPATIAL HISTORY OF ICARIAN COMMUNISM John Derek McCorquindale Department of French and Italian Master of Arts Prior to the 1848 Revolution in France, a democrat and communist named Étienne Cabet organized one of the largest worker’s movements in Europe. Called “Icarians,” members of this party ascribed to the social philosophy and utopian vision outlined in Cabet’s 1840 novel, Voyage en Icarie , written while in exile. This thesis analyzes the conception of space developed in Cabet’s book, and tracks the group’s actual spatial practice over the next seventeen years. During this period, thousands of Icarians led by Cabet attempted to establish an actual colony in the wilderness of the United States. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

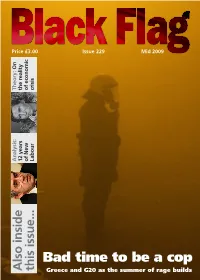

Bad Time to Be a Cop

Price £3.00 Analysis: Theory: On Also inside 12 years the reality of New of economic this issue... Labour crisis Bad time to be a cop a be to time Bad Greece and G20 as the summer of rage builds rage of summer the as G20 and Greece Issue 229 Mid 2009 Editorial Welcome to issue 229 of Black Flag, the fourth to be published by the ‘new’ editorial collective since the re-launch in October 2007. We are still on-track to maintaining our bi- annual publishing objective; it is, however, difficult at times as each publication deadline looms closer, to meet this commitment. We are a small collective, and would once again like to take this opportunity to invite readers to submit articles and indeed, fresh bodies to get involved. Remember, the future of Black Flag, as always, lies with the support of its readership and the anarchist movement in general. We would like to see Black Flag flourish and become a regular (ideally quarterly), broad-based, non-sectarian class- struggle anarchist publication with a national identity. In Black Flag 228, we reported that we had approached the various anarchist federations and groups with a proposal for increased co- operation. Response has generally been slow and spasmodic. However, it has been enthusiastically taken up by the Anarchist Federation, who Barriers: Some of the obstacles laid out which stop us from changing things can seem have submitted an AF perspective insurmountable. Picture: Anya Brennan. on the current economic crisis and a report on a new anarchist archive in Nottingham, written by an AF member involved with the project. -

David Harvey

david harvey THE RIGHT TO THE CITY e live in an era when ideals of human rights have moved centre stage both politically and ethically. A great deal of energy is expended in promoting their sig- nificance for the construction of a better world. But for Wthe most part the concepts circulating do not fundamentally challenge hegemonic liberal and neoliberal market logics, or the dominant modes of legality and state action. We live, after all, in a world in which the rights of private property and the profit rate trump all other notions of rights. I here want to explore another type of human right, that of the right to the city. Has the astonishing pace and scale of urbanization over the last hundred years contributed to human well-being? The city, in the words of urban sociologist Robert Park, is: man’s most successful attempt to remake the world he lives in more after his heart’s desire. But, if the city is the world which man created, it is the world in which he is henceforth condemned to live. Thus, indirectly, and without any clear sense of the nature of his task, in making the city man has remade himself.1 The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from that of what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire. The right to the city is far more than the indi- vidual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. -

Haymarket Riot (Chicago: Alexander J

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS1 MONUMENT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Haymarket Martyrs' Monument Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 863 South Des Plaines Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Forest Park Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code: 031 Zip Code: 60130 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures 1 ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_Q_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTrjPT LANDMARK on by the Secreury 01 j^ tai-M NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS' MONUMENT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National_P_ark Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Rebel Cities: from the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution

REBEL CITIES REBEL CITIES From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution David Harvey VERSO London • New York First published by Verso 20 12 © David Harvey All rights reserved 'Ihe moral rights of the author have been asserted 13579108642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London WI F OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 1120 I www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books eiSBN-13: 978-1-84467-904-1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harvey, David, 1935- Rebel cities : from the right to the city to the urban revolution I David Harvey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-84467-882-2 (alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-84467-904-1 I. Anti-globalization movement--Case studies. 2. Social justice--Case studies. 3. Capitalism--Case studies. I. Title. HN17.5.H355 2012 303.3'72--dc23 2011047924 Typeset in Minion by MJ Gavan, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Vail For Delfina and all other graduating students everywhere Contents Preface: Henri Lefebvre's Vision ix Section 1: The Right to the City The Right to the City 3 2 The Urban Roots of Capitalist Crises 27 3 The Creation of the Urban Commons 67 4 The Art of Rent 89 Section II: Rebel Cities 5 Reclaiming the City for Anti-Capitalist Struggle 115 6 London 201 1: Feral Capitalism Hits the Streets 155 7 #OWS: The Party of Wall Street Meets Its Nemesis 159 Acknowledgments 165 Notes 167 Index 181 PREFACE Henri Lefebvre's Vision ometime in the mid 1970s in Paris I came across a poster put out by S the Ecologistes, a radical neighborhood action movement dedicated to creating a more ecologically sensitive mode of city living, depicting an alternative vision for the city. -

Martyrdom Without End the Case Was Called a 'Never Ending Wrong.' It Still Inspires Wrong-Headedness

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118739039455001441 BOOKS Martyrdom Without End The case was called a 'never ending wrong.' It still inspires wrong-headedness. By Robert K. Landers Aug. 18, 2007 1201 a.m. ET Sacco & Vanzetti By Bruce Watson Viking, 433 pages, $25.95 Furious at the indictments of his fellow anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti -- charged with the murder of a shoe-factory paymaster and his guard in South Braintree, Mass. -- Mario Buda headed for New York City in September 1920. When he got there, he obtained a horse and wagon and placed in it a large dynamite bomb filled with cast-iron sash weights and equipped with a timer. On a Thursday morning, he drove to the corner of Wall and Broad Streets, parked across the street from J.P. Morgan and Co. and disappeared. The noontime explosion killed 33 people, injured several hundred and caused millions of dollars in property damage. His philosophical point made, Buda soon returned to Italy, beyond the reach of American law. William J. Flynn, director of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation, blamed the Wall Street bombing on the Galleanists, militant followers of the deported anarchist leader Luigi Galleani -- "the same group of terrorists," he said, that was responsible for coordinated bombings on June 2, 1919, in Washington and six other cities. Buda was indeed a Galleanist -- and so were Sacco and Vanzetti. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 08 January 2014 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Thomas, S. (2011) 'Outtakes and outrage : the means and ends of suicide terror.', Modern ction studies (MFS)., 57 (3). pp. 425-449. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2011.0062 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2011 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modern ction studies (MFS), 57, 3, Fall, 2011, pages 425-449. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Thomas 425 outtakes and outrage: the means and ends of f suicide terror Samuel Thomas Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief. —Gospel of Mark, 9:24 For perverse unreason has its own logical processes. —Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent In his introduction to The Plague