117. Ovarian Lesions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Androgen Excess in Breast Cancer Development: Implications for Prevention and Treatment

26 2 Endocrine-Related G Secreto et al. Androgen excess in breast 26:2 R81–R94 Cancer cancer development REVIEW Androgen excess in breast cancer development: implications for prevention and treatment Giorgio Secreto1, Alessandro Girombelli2 and Vittorio Krogh1 1Epidemiology and Prevention Unit, Fondazione IRCCS – Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milano, Italy 2Anesthesia and Critical Care Medicine, ASST – Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Milano, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to G Secreto: [email protected] Abstract The aim of this review is to highlight the pivotal role of androgen excess in the Key Words development of breast cancer. Available evidence suggests that testosterone f breast cancer controls breast epithelial growth through a balanced interaction between its two f ER-positive active metabolites: cell proliferation is promoted by estradiol while it is inhibited by f ER-negative dihydrotestosterone. A chronic overproduction of testosterone (e.g. ovarian stromal f androgen/estrogen balance hyperplasia) results in an increased estrogen production and cell proliferation that f androgen excess are no longer counterbalanced by dihydrotestosterone. This shift in the androgen/ f testosterone estrogen balance partakes in the genesis of ER-positive tumors. The mammary gland f estradiol is a modified apocrine gland, a fact rarely considered in breast carcinogenesis. When f dihydrotestosterone stimulated by androgens, apocrine cells synthesize epidermal growth factor (EGF) that triggers the ErbB family receptors. These include the EGF receptor and the human epithelial growth factor 2, both well known for stimulating cellular proliferation. As a result, an excessive production of androgens is capable of directly stimulating growth in apocrine and apocrine-like tumors, a subset of ER-negative/AR-positive tumors. -

Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty Melissa Schoelwer, MD and Erica A Eugster, MD Section of Pediatric Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana Send correspondence to: 705 Riley Hospital Drive, Room 5960 Indianapolis, IN 46202 Phone: 317-944-3889 Fax: 317-944-3882 Email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Schoelwer, M., & Eugster, E. A. (2016). Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty. In Puberty from Bench to Clinic (Vol. 29, pp. 230-239). Karger Publishers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000438895 Peripheral Precocious Puberty Abstract There are many etiologies of peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) with diverse manifestations resulting from exposure to androgens, estrogens, or both. The clinical presentation depends on the underlying process and may be acute or gradual. The primary goals of therapy are to halt pubertal development and restore sex steroids to prepubertal values. Attenuation of linear growth velocity and rate of skeletal maturation in order to maximize height potential are additional considerations for many patients. McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) and Familial Male-Limited Precocious Puberty (FMPP) represent rare causes of PPP that arise from activating mutations in GNAS1 and the LH receptor gene, respectively. Several different therapeutic approaches have been investigated for both conditions with variable success. Experience to date suggests that the ideal therapy for precocious puberty secondary to MAS in girls remains elusive. In contrast, while the number of treated patients remains small, several successful therapeutic options for FMPP are available. -

Precocious Puberty Children with Spina Bi�Da and Hydrocephalus May Start Puberty Earlier Than Their Peers

SBA National Resource Center: 800-621-3141 Precocious Puberty Children with Spina Bida and hydrocephalus may start puberty earlier than their peers. What is Puberty? If major breast development starts before age 8, it is considered early. (Sometimes girls will have some Puberty refers to normal body changes that lead to breast development, with no other signs of puberty. maturity and the ability to have children. Normal puberty This isolated change may be normal.) begins between ages 8 and 12 in girls and between 9 and 14 in boys. Hormones made in the brain control the timing and sequence of puberty. These hormones What are the stages of normal puberty in boys? stimulate other parts of the body to make sex hormones. The usual sequence in boys is: The sex hormones, especially estrogen in girls and testosterone in boys, cause sexual maturation. • The testicles grow larger. • The penis grows larger. What are the stages of normal puberty in girls? • Pubic hair grows. The physical changes seen in puberty are labeled by “Tanner staging.” Stage 1 is child-like (before puberty) • There is a growth spurt.rt. and stage 5 is full maturity. The usual sequence in girls is: • Other body hair grows.s. • Breasts start to develop. If boys show major developmentelopment • Hips widen and a there is a growth spurt that usually before age 9, it is considereddered lasts about three to four years. early. Early puberty in girls or boys is called • Pubic hair grows (three-to-six months after breasts “Precocious Puberty.” develop). • Other body hair grows. -

Precocious Puberty: a Red Flag for Malignancy in Childhood

CLINICAL Paul R. D’Alessandro, MD, MSc, Jillian Hamilton, MBChB, Karine Khatchadourian, MD, MSc, Ewa Lunaczek-Motyka, MD, Kirk R. Schultz, MD, Daniel Metzger, MD, Rebecca J. Deyell, MD, MHSc Precocious puberty: A red flag for malignancy in childhood Three clinical cases of precocious puberty resulting from rare but serious functional solid tumors in children highlight the need for physicians to identify the condition early and refer to tertiary care to minimize morbidity and optimize survival. ABSTRACT: Pediatric solid tumors have a range of 1-3 Dr D’Alessandro is a pediatric hematology/ abnormalities. These tumors may present clinical presentations, including those driven by oncology subspecialty resident in the with early onset of isosexual or contrasexual the ectopic production of hormones secreted by Division of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, puberty as a first symptom. Treatment may some malignancies. Functional tumors lead to a and Bone Marrow Transplant, Department involve surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radio- variety of presentations, including Cushing syn- of Pediatrics, University of British therapy. Genetic testing or counseling may be drome, growth acceleration, abnormal virilization Columbia, British Columbia Children’s indicated for families. Early identification mini- or feminization, and hypertension with electrolyte Hospital Research Institute. mizes disease-related morbidity and mortality abnormalities. Precocious puberty, the onset of Dr Hamilton is a general practice specialty and optimizes outcomes. We present illustrative secondary sexual characteristics before age 8 in trainee, NHS Forth Valley, Larbert, cases of functional solid tumors in children from girls or 9 in boys, may be a warning sign of occult United Kingdom. Dr Khatchadourian is a British Columbia with the aim of educating malignancy. -

Precocious Puberty

Precocious Puberty The Pituitary Gland: The "Master Gland" The pituitary gland, which is often referred to as the "master gland", regulates the release of most of the body's hormones (chemical messengers that send information to different parts of the body). It is a pea-sized gland that is located underneath the brain. The pituitary gland controls the release of thyroid, adrenal, growth and sex hormones. The hypothalamus, located in the brain above the pituitary gland, regulates the release of hormones from the pituitary gland. Hormones: The "Chemical Messengers" Chemical messengers that carry information from one cell to another in the body. Hormones are carried throughout body by the blood, and are responsible for regulating many body functions. The body makes many hormones (e.g., thyroid, growth, sex and adrenal hormones) that work together to maintain normal bodily function. Hormones involved in the control of puberty include: GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone, which comes from the brain in boys and in girls. Other androgens from the adrenal glands (located near the kidneys) produce pubic and axillary hair at the time of puberty. Estrogen: A female sex hormone, which is responsible for breast development in girls. It is made mainly by the ovaries, but is also present in boys in smaller amounts. Sex Hormones: Responsible for the development of pubertal signs as well as changes in behavior and the ability to have children. Precocious Puberty Precocious puberty means having signs of puberty (e.g., pubic hair or breast development) at an earlier age than usual. Normal Puberty There is a wide range of ages at which individuals normally start puberty. -

Precocious Puberty Andrew Muir Pediatrics in Review 2006;27;373 DOI: 10.1542/Pir.27-10-373

Precocious Puberty Andrew Muir Pediatrics in Review 2006;27;373 DOI: 10.1542/pir.27-10-373 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/27/10/373 Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned, published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2006 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601. Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at UNIV OF CHICAGO on May 23, 2013 Article endocrine Precocious Puberty Andrew Muir, MD* Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to: 1. Know the normal ages of pubertal onset in boys and girls. Author Disclosure 2. Discuss the clinical signs of puberty, their usual sequence of appearance, and their Dr Muir did not typical rate of progression. disclose any financial 3. Use the physiology of puberty to diagnose the cause of abnormal puberty. relationships relevant 4. Describe the factors involved in the appropriate management of precocious puberty. to this article. 5. Determine whether to follow or refer children who have signs of early puberty. Introduction Although precocious puberty has standard clinical definitions and diagnostic tests are improving, the management of children who have signs of early puberty has become more complex in some ways during the last decade than ever before. This review illustrates how an understanding of the anatomy and physiology of puberty forms the foundation for managing children who experience puberty early. -

Virilization and Enlarged Ovaries in a Postmenopausal Woman

Please do not remove this page Virilization and Enlarged Ovaries in a Postmenopausal Woman Guerrero, Jessenia; Marcus, Jenna Z.; Heller, Debra https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454200004646?l#13643490680004646 Guerrero, J., Marcus, J. Z., & Heller, D. (2017). Virilization and Enlarged Ovaries in a Postmenopausal Woman. In International Journal of Surgical Pathology (Vol. 25, Issue 6, pp. 507–508). Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3125WCP This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/25 21:27:45 -0400 Virilization and Enlarged Ovaries in a Postmenopausal Woman Abstract: A patient with postmenopausal bleeding and virilization was found to have bilaterally enlarged ovaries with a yellow cut surface. Histology revealed cortical stromal hyperplasia with stromal hyperthecosis. This hyperplastic condition should not be mistaken for an ovarian neoplasm. Key words: Ovary, ovarian neoplasms, virilization Introduction Postmenopausal women who present with clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism are often presumed to have an androgen-secreting tumor, particularly if there is ovarian enlargement. Gross findings in the ovaries can help exclude an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor and histologic findings can confirm the gross findings. Case A 64 year old woman with abnormal hair growth, male pattern baldness, clitorimegaly and postmenopausal bleeding presented to the clinic for evaluation of a possible hormone secreting tumor. Pre-operative work-up revealed bilateral ovarian enlargement, measuring 4 cm in greatest dimension, without evidence of an ovarian or adrenal tumor. -

Downloaded from Bioscientifica.Com at 09/25/2021 06:32:18PM Via Free Access

1 184 A B Hansen and others Sex steroids in adolescencel 184:1 R17–R28 Review DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE Sex steroid action in adolescence: too much, too little; too early, too late A B Hansen 1, D Wøjdemann1, C H Renault1, A T Pedersen 2, K M Main1, L L Raket3,4, R B Jensen1 and A Juul 1 Correspondence 1Department of Growth and Reproduction, 2Department of Gynecology and Fertility Clinic, Rigshospitalet, University should be addressed of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Hovedstaden, Denmark, and 4Clinical Memory to A Juul Research Unit, Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Email [email protected] Abstract This review aims to cover the subject of sex steroid action in adolescence. It will include situations with too little sex steroid action, as seen in for example, Turners syndrome and androgen insensitivity issues, too much sex steroid action as seen in adolescent PCOS, CAH and gynecomastia, too late sex steroid action as seen in constitutional delay of growth and puberty and too early sex steroid action as seen in precocious puberty. This review will cover the etiology, the signs and symptoms which the clinician should be attentive to, important differential diagnoses to know and be able to distinguish, long-term health and social consequences of these hormonal disorders and the course of action with regards to medical treatment in the pediatric endocrinological department and for the general practitioner. This review also covers situations with exogenous sex steroid application for therapeutic purposes in the adolescent and young adult. This includes gender-affirming therapy in the transgender child and hormone treatment of tall statured children. -

What Is and What Is Not PCOS (Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome)?

What is and What is not PCOS (Polycystic ovarian syndrome)? Chhaya Makhija, MD Assistant Clinical Professor in Medicine, UCSF, Fresno. No disclosures Learning Objectives • Discuss clinical vignettes and formulate differential diagnosis while evaluating a patient for polycystic ovarian syndrome. • Identify an organized approach for diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome and the associated disorders. DISCUSSION Clinical vignettes of differential diagnosis Brief review of Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) Therapeutic approach for PCOS Clinical vignettes – Case based approach for PCOS Summary CASE - 1 • 25 yo Hispanic F, referred for 5 years of amenorrhea. Diagnosed with PCOS, was on metformin for 2 years. Self discontinuation. Seen by gynecologist • Progesterone withdrawal – positive. OCP’s – intolerance (weight gain, headache). Denies galactorrhea. Has some facial hair (upper lips) – no change since teenage years. No neurological symptoms, weight changes, fatigue, HTN, DM-2. • Currently – plans for conception. • Pertinent P/E – BMI: 24 kg/m², BP= 120/66 mm Hg. Fine vellus hair (upper lips/side burns). CASE - 1 Labs Values Range TSH 2.23 0.3 – 4.12 uIU/ml Prolactin 903 1.9-25 ng/ml CMP/CBC unremarkable Estradiol 33 0-400 pg/ml Progesterone <0.5 LH 3.3 0-77 mIU/ml FSH 2.8 0-153 mIU/ml NEXT BEST STEP? Hyperprolactinemia • Reported Prevalence of Prolactinomas: of clinically apparent prolactinomas ranges from 6 –10 per 100,000 to approximately 50 per 100,000. • Rule out physiological causes/drugs/systemic causes. Mild elevations in prolactin are common in women with PCOS. • MRI pituitary if clinically indicated (to rule out pituitary adenoma). Prl >100 ng/ml Moderate Mild Prl =50-100 ng/ml Prl = 20-50 ng/ml Typically associated with Low normal or subnormal Insufficient progesterone subnormal estradiol estradiol concentrations. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/148229 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. THE POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME SOME PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL, DIAGNOSTICAI, AND THERAPEUTICAL ASPECTS M.J. HEINEMAN THE POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME SOME PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL, DIAGNOSTICAL AND THERAPEUTICAL ASPECTS PROMOTOR PROF DR R ROLLAND THE POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME SOME PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL, DIAGNOSTICAL AND THERAPEUTICAL ASPECTS PROEFSCHRIFT ICR VLRKRIIbING VAN Dì С.RAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE GENEFSKUNDE AAN DE кАТНОІІНКЬ UMVERSIIHI IF NIJMEGEN OP GF/AG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF DR I H G I GlbbBERb VOI GENS BESLUIT \ΛΝ НЕТ COI LFGL \AN DI ( ANEN IN HET OPFNHAAR 11· VERDEDIGEN OP VRIJDAG 17 DECEMIH R I9S: DFS NAMIDDAGS TE 2 UUR PRFCIFS DOOR MAAS JAN HEINEMAN OEBORFN TF VFl Ρ (GFI DFRI AND) DRlk ΓΛΜΜΙΝΟΑ B\ ARMIfcM To the women who volunteered as subjects for this study, and to the many couples suffering from infertility who inspired me to undertake this investigation. WOORD VOORAF Het in dit proefschrift beschreven onderzoek vond plaats op de Poli kliniek voor Gynaecologische Endocrinologie en Infertiliteit (hoofd: Prof. Dr. R. Rolland) van het Instituut voor Obstetric en Gynaecologie (hoofden: Prof. Dr. Т.К. A.B. Eskes en Prof. Dr. J.L. Mastboom) van het Sint Radboudziekenhuis, Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen. Het was voor mij een unieke ervaring te ondervinden welke enorme mogelijkheden er binnen de Medische Faculteit en in het bijzonder bin nen het Instituut voor Obstetric en Gynaecologie bestaan tot het ver richten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek. -

Precocious Puberty Dominique Long, MD Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Briefin Precocious Puberty Dominique Long, MD Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. AUTHOR DISCLOSURE Dr Long has disclosed Precocious puberty (PP) has traditionally been defined as pubertal changes fi no nancial relationships relevant to this occurring before age 8 years in girls and 9 years in boys. A secular trend toward article. This commentary does not contain fi a discussion of an unapproved/investigative earlier puberty has now been con rmed by recent studies in both the United use of a commercial product/device. States and Europe. Factors associated with earlier puberty include obesity, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDC), and intrauterine growth restriction. In 1997, a study by Herman-Giddens et al found that breast development was present in 15% of African American girls and 5% of white girls at age 7 years, which led to new guidelines published by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society (LWPES) proposing that breast development or pubic hair before age 7 years in white girls and age 6 years in African-American girls should be evaluated. More recently, Biro et al reported the onset of breast development at 8.8, 9.3, 9.7, and 9.7 years for African American, Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, and Asian study participants, respectively. The timing of menarche has not been shown to be advancing as quickly as other pubertal changes, with the average age between 12 and 12.5 years, similar to that reported in the 1970s. In boys, the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network study recently found the mean age for onset of testicular enlargement, usually the first sign of gonadarche, is 10.14, 9.14, and 10.04 years in non-Hispanic white, African American, and Hispanic boys, respectively. -

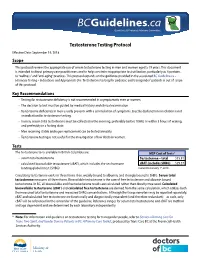

2. Testosterone Testing

Guidelines & Protocols Advisory Committee Testosterone Testing Protocol Effective Date: September 19, 2018 Scope This protocol reviews the appropriate use of serum testosterone testing in men and women aged ≥ 19 years. This document is intended to direct primary care practitioners and to help constrain inappropriate test utilization, particularly as it pertains to “wellness” and “anti-aging” practices. This protocol expands on the guidance provided in the associated BC Guideline.ca – Hormone Testing – Indications and Appropriate Use. Testosterone testing for pediatric and transgender* patients is out of scope of this protocol. Key Recommendations • Testing for testosterone deficiency is not recommended in asymptomatic men or women. • The decision to test must be guided by medical history and clinical examination. • Testosterone deficiency in men usually presents with a constellation of symptoms. Erectile dysfunction in isolation is not an indication for testosterone testing. • In men, serum total testosterone must be collected in the morning, preferably before 10AM, or within 3 hours of waking, and preferably in a fasting state. • Men receiving stable androgen replacement can be tested annually. • Testosterone testing is not useful for the investigation of low libido in women. Tests The testosterone tests available in British Columbia are: MSP Cost of Tests1 • serum total testosterone Testosterone – total $15.81 • calculated bioavailable testosterone (cBAT), which includes the sex hormone cBAT (includes SHBG) $29.37 binding globulin test (SHBG) Current to January 1st, 2018 Circulating testosterone exists in three forms: free, weakly bound to albumin, and strongly bound to SHBG. Serum total testosterone measures all three forms. Bioavailable testosterone is the sum of free testosterone and albumin bound testosterone.