(JW) and Jodi Wurgler (Jow) Interviewer: Tom Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jump to It What’S It Like to Skydive? STACEY POST Reports

word watch AMANDA LAUGESEN says g’day to some Australianisms. his year the Australian National Dictionary I remember the way they had of putting Centre celebrates the 25th anniversary things, like if a bit of country was hard Tof its core work, the Australian National country, they’d say: ‘Aw, she’s bad, that end Dictionary (AND). of the place. Saw a bandicoot with a cut The AND, edited by WS Ramson, is a dictionary lunch round his neck out there.’ of Australianisms – that is, words and meanings bonzer—surpassingly good of words that have originated in, or have 1959 H. DRAKE-BROCKMAN West Coast special significance to, Australia. Stories. Hail, beauteous land! hail, bonzer Modelled on the Oxford English Dictionary, West Australia; /Compared with you, all entries in the AND, which number others are a failure. approximately 10,000 headwords, include a mate boomerang v. series of quotations which tell the history of 1983 Bulletin. When they call you ‘mate’ in the word and how it has been used over time. 1891 Worker. Australia's a big country / An’ the N.S.W. Labor Party it is like getting a kiss Freedom's humping bluey / And Freedom’s The dictionary was a milestone in the from the Mafia. on the wallaby / Oh don’t you hear her lexicography of Australian English and provides Cooee, / She’s just begun to boomerang / The second edition of the AND, currently being invaluable insight into the rich literature, She’ll knock the tyrants silly. edited by Bruce Moore, will include more politics, and culture of Australia. -

Funkin-For-Jamaica (Wax Poetics)

“Invaluable” —Jazz Times Coltrane year, fusing rap and rock together on Run-DMC’s “Rock Box” “Tom Browne, he’s just an ordinary guy.” What he’s saying (with the aid of Don Blackman/Lenny White sideman Eddie is, “This isn’t even his music; what’s he doing here?” It was on Martinez on the track’s blazing guitar lead.) He wasn’t the kind of derogatory, and that feeling permeated through a lot Coltrane only one of the Kats to move behind the scenes as hip-hop of the Kats. exploded around them: Denzil Miller arranged Kurtis Blow’s Wright: [’Nard] sold 200,000 copies without any promotion. The “Christmas Rappin’ ”; Don Blackman played the piano lead But [GRP] told me it wasn’t marketable, because they needed John Coltrane on the Fat Boys’ classic “Jail House Rap”; Bernard Wright a bin for it in the record store. You can’t have a record with worked on Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew’s Oh, My traditional jazz and funk and R&B on the same album, they Interviews God! album. were saying. But that’s what Jamaica, Queens, was. As hip-hop exploded, the next generation of would-be Miller: Right after Tom and Bernard did their albums, I Edited by Kats laid down their instruments and picked up mics. Mean- talked to Dr. George Butler, who was the head of jazz at Chris DeVito while, the arrival of crack and the presence of violent kingpins Columbia, and said, “I’m thinking about doing my own al- like Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nichols tainted the area’s safe, middle- bum. -

Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download

aretha franklin discography torrent download Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d32277da864db8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d322789d5f4e08 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

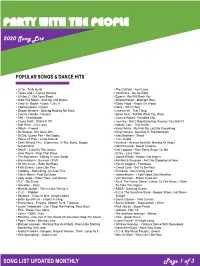

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Episode 67 How to Be Human Part 2 1 Don't Feed the Trolls Podcast

Episode 67 How To Be Human Part 2 1 Nate: Welcome back to the How to Be Human series. No, that is not some sort of plan to become a better person, that is Matt McDonald’s new album for his band The Classic Crime. But this is a podcast doing the commentary on each song off the new record which is called How to Be Human. And this is part 2 of a three part series where we discuss tracks 5-8 on the record. Matt: Yes, and if you’re a patron of this podcast, you’ve likely already heard this, because we’re posting the series early on our Patreon. And if you’re interested in getting early podcasts and bonus content like our Troll Talk podcast, go to patreon.com/dontfeedthetrolls and pledge at least a dollar month to support our podcast and you’ll get a bunch of cool stuff, right Nate? Nate: Yeah, people’ll have been coming on board. We’re getting lots of people who want that extra BOCON, that extra episode. This summer we’re actually going to be taking a break from the podcast, but we’re not going to be taking a break from the actual Patreon Troll Talk episodes, right? Matt: Yeah, Don’t Feed The Trolls might take a break while I’m on the road, but we are still going to be chatting and doing Troll Talks. It’s an unedited podcast by Nate and I, where we just talk about things our patrons would like us to talk about. -

Chris Silva 845-473-5288 #101 Bardavon Gala 2017: Aretha

Immediate Release: February 24, 2017 Contact: Chris Silva 845-473-5288 #101 Bardavon Gala 2017: Aretha Franklin Sunday, March 12 at 7pm at the Bardavon She is both a 20th and 21st century musical and cultural icon known the world over simply by her first name. The reigning and undisputed “Queen Of Soul” has created an amazing legacy that spans an incredible six decades. Her many countless classics include “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” “Chain Of Fools,” “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)”; her own compositions “Think,” “Daydreaming” and “Call Me”; her definitive versions of “Respect” and “I Say A Little Prayer”; and global hits like “Freeway Of Love,” “Jump To It,” and “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me).” The recipient of the U.S.A.’s highest civilian honor, The Presidential Medal Of Freedom, an 18 (and counting) Grammy Award winner – a Grammy Lifetime Achievement and Grammy Living Legend Award winner, Aretha Franklin’s powerful, distinctive gospel-honed vocal style has influenced countless singers across multi-generations, justifiably earning her Rolling Stone magazine’s No. 1 placing on the list of “The Greatest Singers Of All Time.” $275 includes premier performance seating / post-show party / tax-deductible contribution $225 includes preferred performance seating / tax-deductible contribution Gala guests will stroll down the block to the post-show party at the Poughkeepsie Grand Hotel. Where plentiful food and drink, plus stilt walkers, acrobats and jugglers from the Bindlestiff Family Circus will entertain as DJ’s play 60s dance music all night. Cocktail attire. -

Aretha Franklin: Aretha Karriereumspannendes Boxset Deckt Nahezu 60 Jahre Ab

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] ARETHA FRANKLIN: ARETHA KARRIEREUMSPANNENDES BOXSET DECKT NAHEZU 60 JAHRE AB 4-CD- und digitale Sammlung widmet sich mit 81 Tracks der Queen Of Soul, darunter 19 zuvor unveröffentlichte alternative Versionen, Demos, Raritäten, und besondere Live-Performances 2-LP und 1-CD Versionen mit Highlights vom Boxset; alle Formate ab dem 20. November über Rhino erhältlich ARETHA FRANKLIN ARETHA Tracklisting Disc One 1. “Never Grow Old” 2. “You Grow Closer” 3. “Today I Sing The Blues” 4. “Won’t Be Long” 5. “Are You Sure” 6. “Operation Heartbreak” 7. “Skylark” 8. “Runnin’ Out Of Fools” 9. “One Step Ahead” 10. “(No, No) I’m Losing You” 11. “Cry Like A Baby” 12. “A Little Bit Of Soul” 13. “My Kind Of Town (Detroit Is)” – Demo * 14. “Try A Little Tenderness” – Demo * 15. “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)” 16. “Do Right Woman – Do Right Man” 17. “Respect” 18. “A Change Is Gonna Come” 19. “Chain Of Fools” – Alternate Version 20. “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” – UK Single Version 21. “(Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone” 22. “Ain’t No Way” 23. “My Song” 24. “You Send Me” 25. “The House That Jack Built” 26. “Tracks Of My Tears” Disc Two 1. “Baby I Love You” – Live 2. “Son Of A Preacher Man” 3. “Call Me” – Alternate Version * 4. “Let It Be” 5. “Young, Gifted And Black” – Alternate Longer Take * 6. “Bridge Over Troubled Water” – Long Version 7. -

Never Gonna Break My Faith” by the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin

RCA RECORDS, RCA INSPIRATION AND LEGACY RECORDS COLLABORATE TO RELEASE NEVER-BEFORE-HEARD SOLO VERSION OF “NEVER GONNA BREAK MY FAITH” BY THE QUEEN OF SOUL, ARETHA FRANKLIN Cover art photo by Gems/Redferns/Getty Images AVAILABLE TODAY AT ALL DIGITAL SERVICE PROVIDERS – CLICK HERE TO LISTEN “IT WILL SHAKE EVERY FIBER IN YOUR BODY” – CLIVE DAVIS [New York, NY – June 19, 2020] Today, RCA Records, RCA Inspiration and Legacy Records collaborate to release a never-before-heard solo version of “Never Gonna Break My Faith” by the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin, featuring The Boys Choir of Harlem. Co-written by award-winning singer/songwriter Bryan Adams, the Grammy Award winning song was originally released as a duet with Mary J. Blige for the 2006 film Bobby. Over a decade later, the song’s lyrics are as urgent and poignant as ever. Click here to listen. See lyrics below. Clive Davis, Sony Music’s Chief Creative Officer and longtime friend/producer of Ms. Franklin states, “The world is very different now. Change is everywhere and each of us, hopefully, is doing the best he or she can to move forward and make change as positive as possible. Music can play a major role here and Aretha’s performance is chilling. When you read the song’s lyric, and its relevance to what is happening today, it will shake every fiber in your body. Everyone should hear this record. It deserves to be an anthem.” “When I wrote this song, I was channeling Aretha, never thinking that she’d ever actually sing the song,” says Adams. -

Party on the Moon

PARTY ON THE MOON 2021 Song List CURRENT & LEGENDARY DANCE HITS ▪ Billie Eilish - Bad guy ▪ The Weather Girls - It’s Raining Men ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ Rick Springfield - Jessie’s Girl ▪ Post Malone - Circles ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Elvis - Burning Love ▪ Demi Lovato - Sorry Not Sorry ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Ke$ha & Pitbull – Timber ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline Wonderland ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Bryan -

Aretha Franklin STGDC Bio 2014 FINAL-61602867

She is both a 20th and 21st century musical and cultural icon known the world over simply by her first name: Aretha. The reigning and undisputed “Queen Of Soul” has created an amazing legacy that spans an incredible six decades, from her first recording as a teenage gospel star, to her current RCA Records release, ARETHA FRANKLIN SINGS THE GREAT DIVA CLASSICS. Her many countless classics include “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” “Chain Of Fools,” “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)”; her own compositions “Think,” “Daydreaming” and “Call Me”; her definitive versions of “Respect” and “I Say A Little Prayer”; and global hits like “Freeway Of Love,” “Jump To It,” “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me),” her worldwide chart-topping duet with George Michael, and “A Rose Is Still A Rose.” The recipient of the U.S.A.’s highest civilian honor, The Presidential Medal Of Freedom, an eighteen (and counting) Grammy Award winner – the most recent of which was for Best Gospel Performance for “Never Gonna Break My Faith” with Mary J. Blige in 2008 - a Grammy Lifetime Achievement and Grammy Living Legend awardee, Aretha Franklin’s powerful, distinctive gospel-honed vocal style has influenced countless singers across multi-generations, justifiably earning her Rolling Stone magazine’s No. 1 placing on the list of “The Greatest Singers Of All Time.” Marking a glorious reunion with music industry legend Clive Davis (Chief Creative Officer for Sony Music Entertainment) – with whom she worked for the longest period of her recording career, twenty-three years at Arista Records (1980-2003) – Aretha continues her time-honored tradition of creating new music that is innovative, vital and fresh. -

Disrupt Yourself Podcast

Disrupt Yourself Podcast EP IS O DE 172: MICHELLE MCKENNA Welcome to the Disrupt Yourself Podcast. A podcast where we provide strategies and advice for climbing the S Curve of Learning™ in your professional and personal life. Stepping back from who you are to slingshot into who you can be. I'm your host, Whitney Johnson, and joining us today is a super special guest. The person who agreed to be my very first podcast interview in 2016, Michelle McKenna, the first CIO of the NFL. Where among other things, she oversees their technology strategy. Before that, she worked with other world-class companies like Walt Disney and Universal Studios. I talked to Michelle as my very first interview because she is the perfect example of someone who has appended the status quo. Let's listen to a clip about how she was able to not only sell herself to the NFL, but also retool the job rec. Michelle McKenna: You know it’s a really…it’s almost like it was meant to be. I was contemplating what to do with the Constellation/Excelon merger. The CIO position for the combined company was going to be in Chicago. I didn’t want to move to Chicago. And, I was talking to my husband about it, so it was sort of in my mind that I needed to look, but I didn’t want to look for another job. You know, I just, I loved everybody I worked with. But I was a huge sports fan. I was on the Fantasy Football site and there was a link down there ‘about us’, and then there was one for jobs and I opened it and it was the CIO position open. -

Silver Eagle Discography

Silver Eagle USA Discography by Mike Callahan, David Edwards & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Silver Eagle Discography Silver Eagle was a Canadian company headquartered near Toronto at 115 Apple Creek Blvd., Markham, Ontario, Canada. The label was a subsidiary of LaBuick & Associates Media, Inc., and label President was Ed LaBuick. The Media company specialized in TV marketing, and in addition to Silver Eagle also promoted Time-Life. In addition to LPs, Cassettes, and CDs, Silver Eagle also released videos. They established an office in the US at 4 Centre Drive, Orchard Park, NY (later, 777 N. Palm Canyon Dr., Palm Springs, CA), and often licensed product from the Special Products Divisions of the major record labels. They typically would pre-sell an album using 2-minute TV spots in stations across the country, then use that demand to place product in retail stores. They had their own manufacturing plant and distribution system, and according to LaBuick, sold many millions of albums. LaBuick later became head of the Music Division and Special Products Division of the major Quality Label in Canada. Note: All distributed by Silver Eagle unless noted otherwise. Silver Eagle Main Series: Silver Eagle SE-1000 Series: SE-1001 - Peter Marshall Hosts One More Time, The Hits of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey with the Original Artists - Various Artists [1981] (2-LP set) Disc 1: Moonlight Serenade - Tex Beneke/In The Mood - Tex Beneke/Ida - Tex Beneke/Tuxedo Junction - Tex Beneke/Little Brown Jug - Modernaires//Serenade In Blue-Sweet Eloise-At