The Whitsunday Islands: Initial Historical and Archaeological Observations and Implications for Future Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: O’Keeffe, Mornee Jasmin (1991) Over and under: geography and archaeology of the Palm Islands and adjacent continental shelf of North Queensland. Masters Research thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/5bd64ed3b88c4 Copyright © 1991 Mornee Jasmin O’Keeffe. If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please email [email protected] OVER AND UNDER: Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland Thesis submitted by Mornee Jasmin O'KEEFFE BA (QId) in July 1991 for the Research Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts of the James Cook University of North Queensland RECORD OF USE OF THESIS Author of thesis: Title of thesis: Degree awarded: Date: Persons consulting this thesis must sign the following statement: "I have consulted this thesis and I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author,. and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which ',have obtained from it." NAME ADDRESS SIGNATURE DATE THIS THESIS MUST NOT BE REMOVED FROM THE LIBRARY BUILDING ASD0024 STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: "In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it." Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. -

National Parks Contents

Whitsunday National Parks Contents Parks at a glance ...................................................................... 2 Lindeman Islands National Park .............................................. 16 Welcome ................................................................................... 3 Conway National Park ............................................................. 18 Be inspired ............................................................................... 3 Other top spots ...................................................................... 22 Map of the Whitsundays ........................................................... 4 Boating in the Whitsundays .................................................... 24 Plan your getaway ..................................................................... 6 Journey wisely—Be careful. Be responsible ............................. 26 Choose your adventure ............................................................. 8 Know your limits—track and trail classifications ...................... 27 Whitsunday Islands National Park ............................................. 9 Connect with Queensland National Parks ................................ 28 Whitsunday Ngaro Sea Trail .....................................................12 Table of facilities and activities .........see pages 11, 13, 17 and 23 Molle Islands National Park .................................................... 13 Parks at a glance Wheelchair access Camping Toilets Day-use area Lookout Public mooring Anchorage Swimming -

Region Region

THE MACKAY REGION Visitor Guide 2020 mackayregion.com VISITOR INFORMATION CENTRES Mackay Region Visitor Information Centre CONTENTS Sarina Field of Dreams, Bruce Highway, Sarina P: 07 4837 1228 EXPERIENCES E: [email protected] Open: 9am – 5pm, 7 days (May to October) Wildlife Encounters ...........................................................................................4–5 9am – 5pm Monday to Friday (November to April) Nature Reserved ..................................................................................................6–7 9am – 3pm Saturday Hooked on Mackay ...........................................................................................8–9 9am – 1pm Sunday Family Fun ..............................................................................................................10–11 Melba House Visitor Information Centre Local Flavours & Culture ............................................................................12–13 Melba House, Eungella Road, Marian P: 07 4954 4299 LOCATIONS E: [email protected] Cape Hillsborough & Hibiscus Coast ...............................................14–15 Open: 9am – 3pm, 7 days Eungella & Pioneer Valley .........................................................................16–17 Mackay Visitor Information Centre Mackay City & Marina .................................................................................. 18–19 320 Nebo Road, Mackay (pre-Feb 2020) Northern Beaches .........................................................................................20–21 -

Regional Investment Prospectus (PDF 5MB)

Council has a determined focus on setting and supporting an active economic and industry development agenda. The Mackay region was forged on the back of the sugar Sometimes we forget that a city’s most valuable asset is industry and in recent years has matured and diversified its people. With such diversity and a strong multicultural in to the resource service hub of Australia. We are home population, our sense of community enables us to come to one of the largest coal terminals in the world that together to support people of all culture, beliefs and accounts for over 7% of the total global seaborne coal backgrounds. #MackayPride coveys that message and exports and we also produce over one third of Australia’s cements a culture of inclusiveness, social cohesion, sugar. community pride and opportunity. While we possess this strong and resilient economic As a fifth generation local, I am enormously proud of this foundation, we continue to leverage off our natural region and know that we are well placed to attract new advantages and look for emerging opportunities. investment and develop partnerships to capitalise on the enormous economic opportunities in the years to come. Investment opportunities are ripe throughout the region and council has a determined focus on setting and supporting an active economic and industry development Greg Williamson agenda. This focus is supported by Council’s suite of Mayor – Mackay Regional Council development incentives which measure up to the best in the country. Of equal importance to the strength of our economy is the strength of our lifestyle choices. -

Distribution, Host Range and Large-Scale Spatial Variability in Black Band Disease Prevalence on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Vol. 69: 41–51, 2006 Published March 23 Dis Aquat Org Distribution, host range and large-scale spatial variability in black band disease prevalence on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia Cathie Page*, Bette Willis School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia ABSTRACT: The prevalence and host range of black band disease (BBD) was determined from sur- veys of 19 reefs within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, Australia. Prevalence of BBD was com- pared among reefs distributed across large-scale cross-shelf and long-shelf gradients of terrestrial or anthropogenic influence. We found that BBD was widespread throughout the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) and was present on 73.7% of the 19 reefs surveyed in 3 latitudinal sectors and 3 cross-shelf positions in the summer of 2004. Although BBD occurred on all mid-shelf reefs and all but one outer- shelf reefs, overall prevalence was low, infecting on average 0.09% of sessile cnidarians and 0.1% of scleractinian corals surveyed. BBD affected ~7% of scleractinian taxa (25 of approximately 350 GBR hard coral species) and 1 soft coral family, although most cases of BBD were recorded on branching Acropora species. Prevalence of BBD did not correlate with distance from terrestrial influences, being highest on mid-shelf reefs and lowest on inshore reefs (absent from 66%, n = 6, of these reefs). BBD prevalence was consistently higher in all shelf positions in the northern (Cooktown/Lizard Island) sector, which is adjacent to relatively pristine catchments compared to the central (Townsville) sec- tor, which is adjacent to a more developed catchment. -

Queensland Islands & Whitsundays

QUEENSLAND ISLANDS & WHITSUNDAYS INCLUDING SOUTHERN GREAT BARRIER REEF 2018 - 2019 HELLO QUEENSLAND ISLANDS & WHITSUNDAYS Perfect for romantic escapes, family holidays or fun getaways with friends, the Whitsunday Coast, Southern Great Barrier Reef region and Queensland’s spectacular islands, offer something for everyone. Discover the Great Barrier Reef, one of Australia’s most remarkable natural gifts! Viewed from below the water or from the air, it is a sight to behold. Charter a yacht and explore the myriad of tropical islands surrounded by azure waters that make up the Whitsundays. For a change of pace, head south and experience nature at its best. See turtles hatch at Mon Repos Conservation Park and amazing marine life around the reef islands or hire a 4WD and explore stunning Fraser Island. As passionate and experienced travel professionals, we understand what goes into creating great holidays. For a holiday you’ll remember and want to tell everyone about, chat with your local Helloworld Travel agent today. The Whitsundays Tangalooma Island Resort Heron Island Image Cover: Beach Club, Hamilton Island Valid 1 April 2018 – 31 March 2019. Image This Page: Hill Inlet, The Whitsundays Contents Navigating This Brochure 4 Travel Tips 6 Top 10 Things To Do 8 Planning Your Holiday 10 Tropical North Queensland Islands 12 Whitsunday Islands 15 Southern Queensland Islands 23 Whitsunday Coast 28 Mackay 46 Southern Great Barrier Reef Region 48 Car Hire 56 Accommodation Index 58 Booking Conditions 59 3 Navigating This Brochure Let Helloworld Travel inspire you to discover these fantastic destinations Australia Accommodation Ratings ADELAIDE & MELBOURNE GOLD COAST THE KIMBERLEY MELBOURNE & VICTORIA NORTHERN TERRITORY The ratings featured in this brochure will provide SOUTH AUSTRALIA BROOME • STATIONS & WILDERNESS CAMPS • CRUISING & VICTORIA a general indication of the standard of accommodation and may alter throughout the year due to a change of circumstance. -

Tourismwhitsundays.Com.Au Visitor Guide 2019/20

VISITOR GUIDE 2019/20 TOURISMWHITSUNDAYS.COM.AU HAMILTON ISLAND Remember Why hamiltonisland.com.au SAVE 10%* WHEN YOU BOOK TWO OR MORE TOURS HEART PONTOON, HARDY REEF, GREAT BARRIER REEF BARRIER GREAT REEF, HARDY PONTOON, HEART WHITEHAVEN BEACH ISLAND ESCAPE CAMIRA SAILING REEFSLEEP & HILL INLET DAY CRUISES ADVENTURE Iconic beaches, lush tropical islands, luxe resorts and the amazing Great Barrier Reef – the Whitsundays is holiday heaven. Dig your toes into the pure sand of Whitehaven Beach, snorkel amongst spectacular marine life and sleep under the stars on the Great Barrier Reef or soak up the scenery on an island-hopping day cruise – your adventure awaits with the region’s premier tour operator. TO BOOK PLEASE CONTACT CRUISE WHITSUNDAYS +61 7 4846 7000 [email protected] cruisewhitsundays.com *TERMS & CONDITIONS - ONLY ONE DISCOUNT IS ELIGIBLE PER BOOKING. DISCOUNT IS NOT AVAILABLE FOR RESORT CONNECTION SERVICES, HAMILTON ISLAND GOLF, HAMILTON ISLAND ADRENALIN, AIRLIE BEACH ATTRACTIONS OR WHITSUNDAYS CROCODILE SAFARI. THE WHITSUNDAYS, A PLACE TRULY ALIVE WITH WONDER… WHITSUNDAYS VISITOR INFORMATION CENTRE Opening late 2019 at Whitsunday Gold Coffee Plantation Bruce Hwy, Proserpine QLD 4800 +61 7 4945 3967 | [email protected] tourismwhitsundays.com.au Tourism Whitsundays acknowledge the traditional owners of this land. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and Elders from other communities living in the Whitsundays today. Tourism Whitsundays would like to thank Brooke Miles - Above and Below Gallery -

Coastal Queensland & the Great Barrier Reef

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Coastal Queensland & the Great Barrier Reef Cairns & the Daintree Rainforest p228 Townsville to Mission Beach p207 Whitsunday Coast p181 Capricorn Coast & the Southern Reef Islands p167 Fraser Island & the Fraser Coast p147 Noosa & the Sunshine Coast p124 Brisbane ^# & Around The Gold Coast p107 p50 Paul Harding, Cristian Bonetto, Charles Rawlings-Way, Tamara Sheward, Tom Spurling, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Coastal BRISBANE FRASER ISLAND Queensland . 4 & AROUND . 50 & THE FRASER Coastal Queensland Brisbane. 52 COAST . 147 Map . 6 Redcliffe ................94 Hervey Bay ............149 Coastal Queensland’s Manly Rainbow Beach .........154 Top 15 . 8 & St Helena Island .......95 Maryborough ..........156 Need to Know . 16 North Stradbroke Island ..96 Gympie ................157 What’s New . 18 Moreton Island ..........99 Childers ...............157 If You Like… . 19 Granite Belt ............100 Burrum Coast National Park ..........158 Month by Month . 21 Toowoomba ............103 Around Toowoomba .....106 Bundaberg .............159 Itineraries . 25 Bargara ............... 161 Your Reef Trip . 29 THE GOLD COAST . .. 107 Fraser Island ........... 161 Queensland Outdoors . 35 Surfers Paradise ........109 Travel with Children . 43 Main Beach & The Spit .. 113 CAPRICORN COAST & Regions at a Glance . 46 Broadbeach, Mermaid THE SOUTHERN & Nobby Beach ......... 115 REEF ISLANDS . 167 MATT MUNRO / LONELY PLANET IMAGES © IMAGES PLANET LONELY / MUNRO MATT Burleigh Heads ......... 116 Agnes Water Currumbin & Town of 1770 .........169 & Palm Beach .......... 119 Eurimbula & Deepwater Coolangatta ............120 National Parks ..........171 Gold Coast Hinterland . 122 Gladstone ..............171 Tamborine Mountain ....122 Southern Reef Islands ...173 Lamington Rockhampton & Around . 174 National Park ..........123 Yeppoon ...............176 Springbrook Great Keppel Island .....178 National Park ..........123 Capricorn Hinterland ....179 DINGO, FRASER ISLAND P166 NOOSA & THE WHITSUNDAY SUNSHINE COAST . -

Whitsunday Scenic Amenity Study

Scenic Amenity Study Whitsunday RegionRegion ScenicScenic Amenity Amenity Study Study WE15037 WE15037 Scenic Amenity Study Prepared for Whitsunday Regional Council March 2017 Scenic Amenity Study Whitsunday Region Scenic Amenity Study Contact Information Document Information Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd Prepared for Whitsunday Regional ABN 57 051 074 992 Council Project Name Whitsunday Region Scenic Level 11 Green Square North Tower Amenity Study 515 St Paul’s Terrace File Reference Q:\WE Jobs Locked Bag 4006 2015\WE15037 Fortitude Valley Qld 4006 Job Reference WE15037 Telephone: 07 3369 9822 Date March 2017 Facsimile: 07 3369 9722 International: +61 7 3369 9822 [email protected] www.cardno.com.au Author(s): Tania Metcher Landscape Architect Craig Wilson Effective Date March 2017 Senior GIS Analyst Approved By: Date Approved: March 2017 Alan Chenoweth Senior Consultant Document Control Description of Author Reviewed Date Revision Signature Signature Version Author Initials Reviewer Initials A 16 February Draft TM AC 1 16 March Final for review TM AC © Cardno 2016. Copyright in the whole and every part of this document belongs to Cardno and may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or form or in or on any media to any person other than by agreement with Cardno. This document is produced by Cardno solely for the benefit and use by the client in accordance with the terms of the engagement. Cardno does not and shall not assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever to any third party arising out of any use or reliance by any third party on the content of this document. -

Seagrass Resources in the Whitsunday Region 1999 and 2000

Information Series QI02043 Seagrass Resources in the Whitsunday Region 1999 and 2000 Stuart Campbell, Chantal Roder, Len McKenzie, & Warren Lee Long* Marine Plant Ecology Group Northern Fisheries Centre Department of Primary Industries, Queensland PO Box 5396 Cairns Qld 4870 *Wetlands International PO Box 787 Canberra, ACT, 2601 ISSN 0727-6273 QI02043 First Published 2002 The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries, 2002. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Department of Primary Industries. Disclaimer Information contained in this publication is provided as general advice only. For application to specific circumstances, professional advice should be sought. Seagrass maps in this report are magnified so that small meadows can be illustrated. Estimates of mapping error (necessary for measuring changes in distribution) are not to be inferred from the scale of these hard-copy presentation maps. These can be obtained from the original GIS database maintained at the Northern Fisheries Centre, Cairns. The Department of Primary Industries, Queensland has taken all reasonable steps to ensure the information contained in this publication is accurate at the time of the survey. Seagrass distribution and abundance can change seasonally and between years, and readers should ensure that they make appropriate enquires to determine whether new information is available on the particular subject matter. The correct citation of this document is Campbell,S.J., Roder,C.A., McKenzie,L.J and Lee Long, W.J. (2002). Seagrass Resources in the Whitsunday Region 1999 and 2000. DPI Information Series QI02043 (DPI, Cairns) 50 pp. -

Port Procedures and Information for Shipping – Whitsundays

Port Procedures and Information for Shipping – Whitsundays December 2018 Creative Commons information © State of Queensland (Department of Transport and Main Roads) 2017 http://creativecommons.org.licences/by/4.0/ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the authors. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it’s recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 13 14 50 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads on 13 74 68. Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Hard copies of this document are considered uncontrolled. Please refer to the Maritime Safety Queensland website for the latest version. Port Procedures and Information for Shipping – Whitsundays – September 2018 Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................................ 6 List of figures ............................................................................................................................... 6 Table of Amendments ................................................................................................................ -

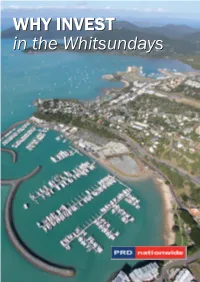

Why Invest in the Whitsundays

WHYWHY INVESTINVEST inin thethe WhitsundaysWhitsundays Whitsunday Region Profile Why invest in the Whitsundays Location Airlie Beach is just one square kilometre of ultimate real estate that is the most exclusive waterfront lifestyle precinct on the planet. With the township book ended by two world class marinas and appointed with a range of cosmopolitan dining and fashion options, the Airlie Beach lifestyle is the perfect foundation. The township is well connected to the 74 Whitsunday Islands, 8 of which are resort islands and the remaining islands are protected National Parks. More than half of the 2600km2 Shire is classified as National Park, ensuring the retention of the area’s natural beauty. Located just 25km inland is Proserpine, home to the region’s hospital, railway station, sugar mill and primary airport. Bowen,situated on the north-eastern coast of the region, is known for its award winning beaches and delicious mangoes. Finally Collinsville, found 87km south-west of Bowen, lies within the resource rich Bowen Basin and is home to several mines. Quality of Life The results of an extensive survey conducted by Tourism and Events Queensland in 2013 revealed that 92% of residents love living here and 58% of residents would not live anywhere else. More than 85% of residents were born elsewhere in Australia, and more than 60% of residents stay for 10 years or more after relocating to the area. Of the residents surveyed, a large majority identified that the tourism industry results in many positive impacts for the area, including more interesting things to do, employment opportunities, events and festivals, improved facilities, increased local pride and greater cultural diversity.