Epidemiology of SARS-Cov2 in Qatar's Primary Care Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Population 2019 السكان

!_ اﻻحصاءات السكانية واﻻجتماعية FIRST SECTION POPULATION AND SOCIAL STATISTICS !+ الســكان CHAPTER I POPULATION السكان POPULATION يعتﺮ حجم السكان وتوزيعاته املختلفة وال يعكسها Population size and its distribution as reflected by age and sex structures and geographical الﺮكيب النوي والعمري والتوزيع الجغراي من أهم البيانات distribution, are essential data for the setting up of اﻻحصائية ال يعتمد علا ي التخطيط للتنمية .socio - economic development plans اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية . يحتوى هذا الفصل عى بيانات تتعلق بحجم وتوزيع السكان This Chapter contains data related to size and distribution of population by age groups, sex as well حسب ا ل ن وع وفئات العمر بكل بلدية وكذلك الكثافة as population density per zone and municipality as السكانية لكل بلدية ومنطقة كما عكسا نتائج التعداد ,given by The Simplified Census of Population Housing & Establishments, April 2015. املبسط للسكان واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ The source of information presented in this chapter مصدر بيانات هذا الفصل التعداد املبسط للسكان is The Simplified Population, Housing & واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ مقارنة مع بيانات تعداد Establishments Census, April 2015 in comparison ٢٠١٠ with population census 2010 تقدير عدد السكان حسب النوع في منتصف اﻷعوام ١٩٨٦ - ٢٠١٩ POPULATION ESTIMATES BY GENDER AS OF Mid-Year (1986 - 2019) جدول رقم (٥) (TABLE (5 النوع Gender ذكور إناث المجموع Total Females Males السنوات Years ١٩٨٦* 247,852 121,227 369,079 *1986 ١٩٨٦ 250,328 123,067 373,395 1986 ١٩٨٧ 256,844 127,006 383,850 1987 ١٩٨٨ 263,958 131,251 395,209 1988 ١٩٨٩ 271,685 135,886 407,571 1989 ١٩٩٠ 279,800 -

Qatar 2022 Overall En

Qatar Population Capital city Official language Currency 2.8 million Doha Arabic Qatari riyal (English is widely used) Before the discovery of oil in Home of Al Jazeera and beIN 1940, Qatar’s economy focused Media Networks, Qatar Airways on fishing and pearl hunting and Aspire Academy Qatar has the third biggest Qatar Sports Investments owns natural gas reserves in the world Paris Saint-Germain Football Club delivery of a carbon-neutral tournament in 2022. Under the agreement, the Global Carbon Trust (GCT), part of GORD, will Qatar 2022 – Key Facts develop assessment standards to measure carbon reduction, work with organisations across Qatar and the region to implement carbon reduction projects, and issue carbon credits which offset emissions related to Qatar 2022. The FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ will kick off on 21 November 2022. Here are some key facts about the tournament. Should you require further information, visit qatar2022.qa or contact the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy’s Tournament sites are designed, constructed and operated to limit environmental impacts – in line with the requirements Media Team, [email protected]. of the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS). A total of nine GSAS certifications have been awarded across three stadiums to date: 21 November 2022 – 18 December 2022 The tournament will take place over 28 days, with the final being held on 18 December 2022, which will be the 15th Qatar National Day. Eight stadiums Khalifa International Stadium was inaugurated following an extensive redevelopment on 19 May 2017. Al Janoub Stadium was inaugurated on 16 May 2019 when it hosted the Amir Cup final. -

Client Site Products

Client Site Products Flame Towers at Hyatt Plaza Shopping Mall. Qatar State of Qatar LPG detection Central Markets Company Ak-Mob Aksaray PL4 PLG8 Al Khayal Restaurant at Hyatt Plaza State of Qatar Multiscan IDI and LPG detectors Al Tazaj Restaurant at Hyatt Plaza State of Qatar Multiscan IDI and LPG detectors Al-Najah Girls Elmentary School Al Ameer. State of Qatar LPG detection Amisragas Beer-Sheva LPG detection Amisragas Tel-Aviv LPG detection Aparcamiento Faro Shopping Algarve Multiscan IDI and CO detectors APICOM/İTÜ University Lab. Maslak/Istanbul PL4, SMART3 H2, CO, Propane Asma Bint abu-Backer Girls elementary school. Al Saad. State of Qatar LPG detection Atofina Korea Methane detection Bakery & Hot food preparation Area in Giant Store Khalifa LPG detection near Khalifa Stadium Balikesir University Balikesir PL4 PLG8 Bank of Greece Athens BIC (Industria) Tarragona Methane detection Biological Refining Psitalia, Greece Bosch Factory Manisa, Turkey Carbon Monoxide detection Botas. Pressure reducing stations Ankara LISA2 IR for CH4 Boys elementary School at Al Shahaniya Al Shahaniya. State of LPG detection Qatar Boys school at Jumailiyah. Ministry of Municipal Jumailiyah. State of LPG detection Affairs & Agriculture- Building Engineering Qatar Department Bulyard Varna, Bulgaria Toluene and Methane detection with SMART3 and Sentox 44 CANE Science Chemical University Cork CH4, O2 and Ammonia detection with Multiscan panel Car Park Stations in various towns all over Greece Greece CO detection with PL4 and S1107CO Carmel Forge Haifa LPG detection Cement Factory Inofita PL4 & LPG detectors Central Agriculture & Pesticides Laboratory. State of Qatar Hydrogen, Oxygen depletion, Ministry of Municipal Affairs & Agriculture. Building Nitrous Oxide, Acetylene, Engineering Dept Propane. -

QU Among Top 350 Varsities Worldwide in the World University

02 Thursday, September 3, 2020 Contact US: Qatar Tribune I EDITORIAL I Phone: 40002222 I ADMINISTRATION & MARKETING I Phone: 40002155, 40002122, Fax: 40002235 P.O. Box: 23493, Doha. Quick read FM, US President’S senior adVisor disCuss ties Governor, mayor of Beirut meet Deputy Prime Minister and Amir congratulates Minister of Foreign Affairs HE president of Vietnam Sheikh Mohammed bin Ab- Qatar’s envoy, review damages dulrahman Al Thani met with THE Amir His Highness Senior Advisor to US President Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Jared Kushner in Doha on and losses from port explosion Thani on Wednesday sent a Wednesday. During the meet- QNA The governor and the mayor of Beirut cable of congratulations to ing, they reviewed bilateral rela- DOHA also hailed the humanitarian role played President of Vietnam Nguyen tions between the two countries by Qatar at this time of crisis by sending Phu Trong on his country’s and other issues of common GOVERNOR of Beirut Judge Marwan medical and relief aid. Independence Day. (QNA) concern. The foreign minister Abboud and Mayor of Beirut Munici- Qatar’s ambassador to Lebanon also affirmed Qatar’s position that pality Eng Jamal Itani separately met met with Secretary-General of the High Deputy Amir calls for a just settlement of with Ambassador of Qatar to Leba- Relief Commission Major-General Mo- congratulates the Palestinian issue on the non HE Mohammed Hassan Jaber Al hammed Khair. basis of international legitimacy Jaber. During the meeting, Khair praised Vietnamese president resolutions and the Arab Peace During the meetings, they reviewed the aid and the great support provided THE Deputy Amir His High- Initiative and on the basis of the losses and damages to the buildings, by Qatar to the Lebanese people amid the ness Sheikh Abdullah bin the two-state solution in a way institutions and homes of citizens follow- ordeal faced by them following the port Hamad Al Thani on Wednes- that promotes security and ing the port explosion in Beirut, as well disaster. -

Qatar Real Estate Q4, 2019.Pdf

Qatar Real Estate Q4, 2019 Indicators Q4 2019 Micro Economics – Current Standings Steady increase in population partially supports the demand for housing. Supply will continue for Total Population* GDP at Current Price* another 2 quarters due to the projects which are currently under construction. 2,773,885 QAR 163.45 Billion Office rental are stabilizing in new CBD areas while old * Nov 2019 * Q2 2019 town is experiencing challenges. Most malls are performing Industrial well in terms of occupancy. Producer Price Index* Production Index* The hospitality still focused on luxury segment, inventory in budget hotel rooms are 61.4 points 109.6 points limited. * Sep 2019 * Aug 2019 Ref: QSA Overall land rates are stabilizing across Qatar. No of Properties Sold Municipalities 1,107 Value of Properties Sold Al Shamal QAR 7.3 Billion Al Khor Ref: MDPS For the period September, October and November 2019 Al Daayen Real Estate Price Index (QoQ) Umm Slal Doha 300 8.0% Al Rayyan 250 6.0% 4.0% 200 2.0% 150 0.0% -2.0% Al Wakra 100 -4.0% 50 -6.0% 0 -8.0% Jul-17 Jul-18 Jul-19 Jan-17 Jan-18 Jan-19 Sep-17 Sep-18 Sep-19 Mar-17 Mar-18 Mar-19 Nov-17 Nov-18 May-18 May-19 May-17 Ref: QCB 2 Residential Q4 2019 YTD Snapshot Supply in Pipeline Expected Delivery Overall Available Units 360,000 90,000 units 2020 Q4 2019 Villa Occupancy 70%* Median Selling Price Median Rental Rate Apartment Occupancy QAR 11,000 PSF QAR 7,000 (2BR) 60%* Ref: AREDC Research Current Annual Yield Key Demand Drivers 5%* * Average 20% 15% Government Companies Residential Concentration Government and companies are taking residential units for their employees under HRA. -

THE QATAR GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROJECT Randall C

LINKING GEOLOGY AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING IN KARST: THE QATAR GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROJECT Randall C. Orndorff U.S. Geological Survey, 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA, [email protected] Michael A. Knight Gannett Fleming, Inc., P.O. Box 67100, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 17106, USA, [email protected] Joseph T. Krupansky Gannett Fleming, Inc., 1010 Adams Avenue, Audubon, Pennsylvania, 19403, USA, [email protected] Khaled M. Al-Akhras Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Robert G. Stamm U.S. Geological Survey, 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA, [email protected] Umi Salmah Abdul Samad Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Elalim Ahmed Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Abstract During a time of expanding population and aging urban Introduction infrastructure, it is critical to have accurate geotechnical Currently, the State of Qatar does not have adequate and geological information to enable adequate design geologic maps at regional and local scales with detailed and make appropriate provisions for construction. This descriptions, proper base maps, GIS, and digital geoda- is especially important in karst terrains that are prone to tabases to adequately support future development. To sinkhole hazards and groundwater quantity and quality better understand the region’s geological and geotech- issues. The State of Qatar in the Middle East, a country nical conditions influencing long term sustainability of underlain by carbonate and evaporite rocks and having future development, the Infrastructure Planning Depart- abundant karst features, has recognized the significance ment (IPD) of the Ministry of Municipality and Environ- of reliable and accurate geological and geotechnical ment (MME) of the State of Qatar has commenced the information and has undertaken a project to develop a Qatar Geologic Mapping Project (QGMP). -

District Energy Space2014

■■ North America District Energy Space 2014 Spotlighting Industry Growth More than 120 million square feet reported District■■ North America Energy Space 2014 Industry Growth around the World Dedicated to the growth and utilization of district energy as a means to enhance energy efficiency, provide more sustainable and reliable energy infrastructure, and contribute to improving the global environment. Established in 1909, the International District Energy Association (IDEA) serves as a vital commu- nications and information hub for the district energy industry, connecting industry professionals and advancing the technology around the world. With headquarters just outside of Boston, Mass., IDEA comprises over 2,000 district heating and cooling system executives, managers, engineers, consultants and equipment suppliers from 23 countries. IDEA supports the growth and utilization of district energy as a means to conserve fuel, increase energy efficiency and resilience, and reduce emissions. The publication of District Energy Space has become an annual tradition for the International District Energy Association since 1990. Each year, IDEA asks all of its member systems in North America (compilation initiated in 1990) and beyond North America (compilation initiated in 2004) to provide information on the number of buildings and their area in square feet that committed or recommitted to district energy service during the previous calendar year. This issue compiles growth that was reported for the calendar year 2014, or previously unreported for recent years. To qualify for consideration in District Energy Space, a renewal would have to be a contracted building or space that had been scheduled to expire and was subject to renewal under a contract with a duration of 10 years or more. -

KPMG Real Estate and Infrastructure Monthly Pulse

KPMG real estate and infrastructure monthly pulse 7 August 2018 Dear all, For any enquiries, please We are pleased to share the latest issue of the KPMG real estate and contact: infrastructure monthly pulse with you. This edition summarizes news articles about the sector in Qatar in July, helping you to stay connected with new and ongoing developments. Real estate Real estate transactions between June 24 to June 28, stood at QAR470 million. Most trading took place in Doha, Umm Salal, Al Rayyan, Al Daayen, Al Shamal, Al Khor, Al Thakhira and Al Shahaniya. Read more Venkatesh United Development Company (UDC) announced another Krishnaswamy milestone in the development of Al Mutahidah Towers, with the Partner, Deal Advisory construction of a bridge connecting the two towers on the 12th KPMG in Qatar floor, at a height of 60m. Read more D: +974 4457 6451 M: +974 5554 1024 Tourism and hospitality T : +974 4457 6444 Qatar’s hospitality sector has made great strides in the past 5 [email protected] years. Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (MDPS) data shows that the number of hotel rooms has grown by around 64 percent from 13,577 in 2013 to 22,288 in 2017, while the number of hotels has grown by around 30 percent, from 83 in 2013 to 108 in 2017. Read more Hamad International Airport served 7.8 million passengers in the second quarter of 2018, with June being particularly busy, with year-on-year growth of 12.56 percent in passenger figures and 8.9 percent in aircraft movements. -

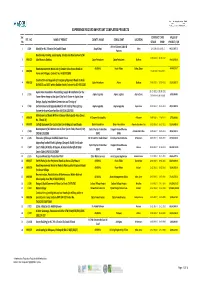

Experience Record Important Completed Projects

EXPERIENCE RECORD IMPORTANT COMPLETED PROJECTS Ser. CONTRACT DATE VALUE OF REF . NO . NAME OF PROJECT CLIENT'S NAME CONSULTANT LOCATION No STRART FINISH PROJECT / QR Artline & James Cubitt & 1 J/149 Masjid for H.E. Ghanim Bin Saad Al Saad Awqaf Dept. Dafna 12‐10‐2011/31‐10‐2012 68,527,487.70 Partners Road works, Parking, Landscaping, Shades and Development of Al‐ 22‐08‐2010 / 21‐06‐2012 2 MRJ/622 Jabel Area in Dukhan. Qatar Petroleum Qatar Petroleum Dukhan 14,428,932.00 Road Improvement Works out of Greater Doha Access Roads to ASHGHAL Road Affairs Doha, Qatar 48,045,328.17 3 MRJ/082 15‐06‐2010 / 13‐06‐2012 Farms and Villages, Contract No. IA 09/10 C89G Construction and Upgrade of Emergency/Approach Roads to Arab 4 MRJ/619 Qatar Petroleum Atkins Dukhan 27‐06‐2010 / 10‐07‐2012 23,583,833.70 D,FNGLCS and JDGS within Dukhan Fields,Contract No.GC‐09112200 Aspire Zone Foundation Dismantling, Supply & Installation for the 01‐01‐2011 / 30‐06‐2011 5 J / 151 Aspire Logistics Aspire Logistics Aspire Zone 6,550,000.00 Tower Flame Image at the Sport City Torch Tower in Aspire Zone Extension to be issued Design, Supply, Installation.Commission and Testing of 6 J / 155 Enchancement and Upgrade Work for the Field of Play Lighting Aspire Logestics Aspire Logestics Aspire Zone 01‐07‐2011 / 25‐11‐2011 28,832,000.00 System for Aspire Zone Facilities (AF/C/AL 1267/10) Maintenance of Roads Within Al Daayen Municipality Area (Zones 7 MRJ/078 Al Daayen Municipality Al Daayen 19‐08‐2009 / 11‐04‐2011 3,799,000.00 No. -

Qatar Facts and Figures

Qatar Facts and Figures1 Location: Middle East, peninsula bordering the Persian Gulf and Saudi Arabia Area: 11,586 sq km (4,473 sq mi) Border Countries: Saudi Arabia, 60 km (37 mi) Natural Hazards: Haze, dust storms, sandstorms common Climate Arid; mild, pleasant winters; very hot, humid summers Environment—Current Issues: Limited natural fresh water resources are increasing dependence on large-scale desalination facilities. Population: 840,296 (July 2010 est.) Median Age: 30.8 years (2010 est.) Population Growth Rate: 0.957% (2010 est.) Life Expectancy at Birth: 75.51 years (2010 est.) HIV/AIDS (people living with): NA 1 Information in this section comes from the following source: Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. “Qatar.” 29 September 2010. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/qa.html 1 © Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center Nationality: Noun: Qatari(s) Adjective: Qatari Sex Ratio: At birth: 1.056 male(s)/female Under 15 years: 1.06 male(s)/female 15-64 years: 2.44 male(s)/female 65 years and over: 1.36 male(s)/female Total population: 1.999 male(s)/female (2010 est.) Ethnic Groups: Arab 40%, Indian 18%, Pakistani 18%, Iranian 10%, Other 14% Religions: Muslim 77.5%, Christian 8.5%, Other 14% (2004 census) Languages: Arabic (official), English commonly used as a second language Literacy: Definition: Persons age 15 and over who can read and write Total population: 89% Male: 89.1% Female: 88.6% (2004 census) Country Name: Conventional long form: State of Qatar Conventional short -

LUSAIL Rising from the Heart of the Arabian Peninsula, Qatar Has Become a Beacon of Sustainable and Continuous Growth Over the Past Two Decades

MAISONS BLANCHES LUSAIL Rising from the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, Qatar has become a beacon of sustainable and continuous growth over the past two decades. Led by an ambitious Vision 2030, the country offers unparalleled investment opportunities. And with the World Cup 2022 in its sights, the future is progressively looking brighter for Qatar. It has become the oasis that promises to quench the thirst of thinkers, dreamers and investors. Qatar is an international hub connected to the rest of the world through the Hamad International Airport QATAR where business and lifestyle merge into one cohesive environment, a place that moves ahead of the time, but one that remains always true to its heritage and identity. Major projects currently under development such as Lusail City and Qatar Rail will play a significant role in further boosting the country’s position as a global leader in the fields of urban architecture and property Where Luxury is Reinvented development. Maisons Blanches - Lusail Qatar’s ambitious vision to build a new, sustainable city that reflects its modern times resulted in one of the most grandiose projects today: Lusail City. Lusail City, located on the coast, in the northern part of the municipality of Al Daayen, is a city built for the future, introducing a modern, contemporary lifestyle while embracing the environment. The city is expected to accommodate up to 260,000 people and is a key attraction as part of Qatar’s 2022 FIFA World Cup. Lusail City is only 15 km away from the centre of Doha, and will be connected to the capital via the Qatar Rail LUSAIL CITY project, making commuting between the two cities convenient and efficient. -

Unesco Hails Qatar Efforts to Save World Heritage

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Barcelona suff er Deportivo INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 4-13, 32 COMMENT 30, 31 Nakilat embarks on low aft er REGION 14 BUSINESS 1-7, 14-16 20,848.00 10,491.15 48.49 ARAB WORLD 14, 15 CLASSIFIED 8-13 further expansion +20.00 +23.92 -0.79 INTERNATIONAL 16-29 SPORTS 1-8 PSG high +010% +0.23% -1060% into global markets Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10391 March 13, 2017 Jumada II 14, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Sheikha Moza visits Sudan projects Unesco hails In brief Qatar eff orts QATAR | Transport to save world GCC Traffi c Week celebrations begin The 33rd GCC Traff ic Week celebrations kicked off yesterday under the theme of ‘Your Life is Trust’. Director General heritage of Public Security Staff Major General Saad bin Jassim al-Khulaifi opened the accompanied exhibition and activities QNA in Doha two years ago to protect world held at Darb Al Saai, in the presence of Doha heritage” chaired by HE Sheikha Al a number of off icials from the Interior Mayassa and representatives from the Ministry and representatives of the Unesco, advisory bodies of the Inter- participating institutions and the nesco Director-General Irina national Union for Conservation of delegations of the Gulf Co-operation Bokova has hailed Qatar’s ef- Nature and the International Council Council (GCC). He toured the stands Uforts in preserving the world on Monuments and Sites. designated to participants from heritage by supporting the United Na- She added that Qatar had adopted government agencies, institutions, tions Educational, Scientifi c and Cul- very important decisions for Unesco companies, civil society, youth and tural Organisation’s initiatives.