SMALL BUSINESS and GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT Albenr N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Product Life Cycle : It's Role in Marketing Strategy/Some Evolving

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANACHAMPAIGN BOOKSTACKS £'*- ^3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/productlifecycle1304gard BEBR FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 1304 The Product Life Cycle: It's Role in Marketing Strategy/Some Evolving Observations About the Life Cycle David M. Gardner College of Commerce and Business Administration Bureau of Economic and Business Research University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign BEBR FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 1304 College of Commerce and Business Administration University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign November 1986 The Product Life Cycle: It's Role in Marketing Strategy/ Some Evolving Observations About the Life Cycle David M. Gardner, Professer Department of Business Administration The Product Life Cycle: It's Role In Marketing Strategy- Some Evolving Observations About The Product Life Cycle The Product Life Cycle is an attractive concept, but one which the common consensus is that it has some descriptive value, but rather limited or non-existent prescriptive value. This paper is based on the premise the Product Life Concept has the potential to become a central, if not, the central concept in marketing theory and practice. Prior to making suggestions on steps toward this ambitious goal, the concept is reviewed along with its major limitations. Based on a review of research evidence published since 1975, it is suggested that three areas need to be explored and expanded. The first is a careful reexamination of the foundation of the concept, then there needs to be a focus on the product life cycle as a dependent variable, and third, there is a need from application of meta-theory criteria to guide future research. -

Customer Relationship Management: a Financial Perspective

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2004 Customer relationship management: A financial perspective Dwain Eldred Lowther Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Recommended Citation Lowther, Dwain Eldred, "Customer relationship management: A financial perspective" (2004). Theses Digitization Project. 2694. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2694 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT A FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration by Dwain Eldred Lowther June 2004 CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT A FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE A Proj ect Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Dwain Eldred Lowther June 2004 Approved by: C.E. Tapie Xohm,X1 'Ph.Dy, Information & Decision Sciences Information & Decision Patrick S. Mclnturff ,/Ph.D. , Department Chair, Management ABSTRACT In an era of increasing competition in the financial services industry, it is imperative that strategic planners, operations personnel and line employees have at their disposal the ability to.call upon information not only about groups of customers, but specific individual customers as well. Providing this sort of analysis at the customer level with any degree of precision requires a great deal of information, and the wherewithal to collect and collate that 'information in a way that can be made easily accessible to the lay or unsophisticated reader. -

A Guide to the U.S. Small Business Administration TABLE of CONTENTS

A Guide to the U.S. Small Business Administration TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Resources for Start-Up Businesses The Planning Phase ................................................................................ 2 Writing a Powerful Business Plan ........................................................... 2 Online Training ....................................................................................... 3 General Finance and Accounting .......................................................... 3 Licensing and Permits ............................................................................ 3 Loans and Funding................................................................................. 3 SBA Loan Programs ............................................................................... 4 Section 2: Resources for Existing Businesses Business Management, Leadership and Human Resource Tools ................................................................... 5 Using Information Technology ............................................................... 5 Finances, Revenue Growth and Loans................................................... 5 SBA Loan Programs ............................................................................... 6 Planning a Business Exit Strategy .......................................................... 6 Contact Opportunities .......................................................................... 7 Disaster Assistance ................................................................................ 7 -

Marketing Strategies During the Product Life Cycle in the Pharmaceutical Industry Natasa Naneva Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 Marketing Strategies During the Product Life Cycle in the Pharmaceutical Industry Natasa Naneva Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Natasa Naneva has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Matthew Knight, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. David Moody, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Judith Blando, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract Marketing Strategies During the Product Life Cycle in the Pharmaceutical Industry by Natasa Naneva MBA, Ashland University, 2008 BS, Sv. Kliment Ohridski - Bitola, 2005 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University November 2018 Abstract Development and implementation of effective marketing strategies during various stages of product life cycle in the pharmaceutical industry are critical to an organization’s successful performance in the marketplace in the 21st century. -

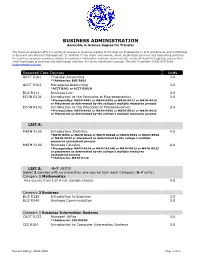

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Associate in Science Degree for Transfer

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Associate in Science Degree for Transfer The Business program offers a variety of courses in business leading to the degrees of Associate in Arts and Science and Certificates in Business and Business Management. In addition to the major coursework, which emphasizes business and accounting practices, the business program combines studies in computer information systems and meets the needs of students targeting careers that meld knowledge of business and information systems. For more information contact: Timothy Fontenette (805) 678-5266 [email protected] Required Core Courses Units ACCT R101 Financial Accounting 3.0 **Advisories: BUS R001 ACCT R102 Managerial Accounting 3.0 *ACCT R101 or ACCT R101H BUS R111 Business Law 3.0 ECON R101 Introduction to the Principles of Macroeconomics 3.0 *Prerequisites: MATH R002 or MATH R005 or MATH R011 or MATH R015 or Placement as determined by the college’s multiple measures process ECON R102 Introduction to the Principles of Microeconomics 3.0 *Prerequisites: MATH R002 or MATH R005 or MATH R011 or MATH R015 or Placement as determined by the college’s multiple measures process LIST A: MATH R105 Introductory Statistics 4.0 *MATH R005 or MATH R014 or MATH R014B or MATH R015 or MATH R032 or MATH R033 or placement as determined by the college’s multiple measures assessment process MATH R106 Business Calculus 4.0 *Prerequisites: MATH R014 or MATH R014B or MATH R015 or MATH R033 or placement as determined by the college’s multiple measures assessment process **Advisories: MATH R115 -

Business Administration (BSBA) 1

Business Administration (BSBA) 1 Business Administration (BSBA) Bachelor's Degree Programs Bachelor of Science in Business Administration The BSBA was developed to afford busy adults a degree option that would recognize the full range of their abilities in a convenient and flexible format. In addition to completing the general curriculum core, all BSBA candidates must complete a business core and a concentration in either accountancy, management or healthcare management. In addition to the core curriculum requirements, BSBA students must complete the business core courses and concentration courses as detailed on the following pages. All students are required to take 120 credits to meet graduation requirements. Business Core Requirements All BSBA majors will take a core of business courses. These courses are the common subjects that differentiate a business degree from other degree programs. The following is a list of these courses. BA-155 Principles of Marketing 3 BA-151 Principles of Management 3 AC-151 Principles of Accounting I 3 AC-152 Principles of Accounting II 3 BL-161 Introduction to Law and Contracts 3 EC-101 Macroeconomic Principles 3 EC-102 Microeconomic Principles 3 EC-300 Statistics for Business Finance and Economics 3 FN-410 Business Finance (required for accounting majors) 3 or FN-401 Introduction to Corporate Finance BA-465 Executive Seminar 3 Total Credits 30 Special Note on Core Curriculum Students in the BSBA programs are encouraged to take CS-150 as part of their natural science requirement. Requirements for Bachelor -

The Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management Usage, Customer Satisfaction, and Revenue Robert Lee Simmons Walden University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Walden University Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2015 The Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management Usage, Customer Satisfaction, and Revenue Robert Lee Simmons Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Business Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Robert Simmons has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Ronald McFarland, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Alexandre Lazo, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. William Stokes, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2015 Abstract The Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management Usage, Customer Satisfaction, and Revenue by Robert L. Simmons MS, California National University, 2010 BS, Excelsior College, 2003 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University September 2015 Abstract Given that analysts expect companies to invest $22 billion in Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems by 2017, it is critical that leaders understand the impact of CRM on their bottom line. -

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Associate in Science Degree | Transfer Degree | Department of Business and Information Systems

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Associate in Science Degree | Transfer Degree | Department of Business and Information Systems The Business Administration curriculum provides a DEGREE OPTIONS broad academic foundation so that graduates may Student must choose an option to graduate: Accounting, transfer to the third year of a senior college or pursue Computer Programming, Management or Marketing immediate employment. Students must select one option Management (12 Credits) from among the Accounting, Computer Programming, Management and Marketing Management options. Accounting Option Requirements: Curriculum Coordinator: Professor Howard A. Clampman This option prepares students with fundamental courses Business Administration Curriculum (Pathways in business and accounting. The option also provides the background for transfer to a senior college and Required Core completion of the baccalaureate degree. Students who wish to pursue a career in finance should select this A. English Composition (6 Credits) option. Upon completion of further appropriate education B. Mathematical and Quantitative Reasoning1 (4 Credits) and training and with experience, the student may qualify C. Life and Physical Sciences2 (3-4 Credits) by state examination as a Certified Public Accountant or as a teacher. SUBTOTAL 13-14 • ACC 112 Principles of Accounting II (4 Credits) Flexible Core • ACC 113 Principles of Intermediate Accounting (4 Credits) A. World Cultures and Global Issues3 (3 Credits) • ACC 115 Accounting Information Systems (3 Credits) B. U.S. Experience in its Diversity3 (3 Credits) • KEY 10 Keyboarding for Computers (1 Credit) C. Creative Expression (3 Credits) Students are advised that there is an AAS degree offered D. Individual and Society3 (3 Credits) in the same discipline. E. Scientific World (3 Credits) Computer Programming Option Requirements: Restricted Elective Select one course from Areas This option provides a range of computer programming A-E. -

School of Business Administration Cooperative Education/Internship Application & Information Packet

School of Business Administration Cooperative Education/Internship Application & Information Packet Faculty Coordinators Accounting, Finance, Entrepreneurship, Management, Marketing Dr. Greg Russell Associate Dean, School of Business Administration Combs 212 606-783-2090 [email protected] Information Systems Dr. Sam Nataraj Professor, Information Systems Combs 218 606-783-9349 [email protected] Morehead State University School of Business Administration Internship Application Revised July 2016 Cooperative Education/Internship Program (CEIP) General Overview The purpose of the MSU Cooperative Education/Internship Program (CEIP) is to offer students the opportunity to obtain college credit and career related experience through participation in employment opportunities. An internship is a pre-professional learning experience that offers meaningful, practical work experience related to a student’s field of study or career interest. Internships allow students to apply principles and theories learned in the classroom in a professional environment and provide students with an opportunity for career exploration and development as well as to learn new skills. It is the student’s responsibility to secure a Cooperative Education/Internship position at a business/industry work site where the student will be engaged in activities related to their academic program and career objectives. The student will perform duties and services as assigned by the work supervisor and CEIP coordinator. In some instances, CEIP credit may be obtained by students with current employers, however, the CEIP proposal must clearly indicate new areas of responsibility or a special project in which the student participates. Students are able to earn three semester credit hours for a minimum of 180 hours of work performed under the supervision of a qualified work-site supervisor. -

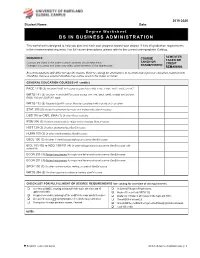

Degree Worksheetbs in Business Administration

2019-2020 Student Name: Date: Degree Worksheet BS IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION This worksheet is designed to help you plan and track your progress toward your degree. It lists all graduation requirements in the recommended sequence. For full course descriptions, please refer to the current undergraduate Catalog. SEMESTER SEQUENCE COURSE TAKEN OR TAKEN OR Courses are listed in the order in which students should take them. CREDIT TRANSFERRED Changes in courses and order may affect other elements of the degree plan. REMAINING Recommendations will differ for specific majors. Refer to catalog for alternatives to recommended general education requirements (GenEds). Courses used for GenEds may not be used in the major or minor. GENERAL EDUCATION COURSES (41 credits) PACE 111B (3) Or other PACE 111 course chosen from 111B, 111C, 111M, 111P, 111S, or 111T WRTG 111 (3) Or other 3-credit WRTG course except 288, 388, 486A, 486B. COMM 390 and 492, ENGL 102 and JOUR 201 apply WRTG 112 (3) Required GenEd course. Must be completed with a grade of C- or better STAT 200 (3) Related requirement for major and mathematics GenEd course LIBS 150 or CAPL 398A (1) Or other GenEd elective IFSM 300 (3) Related requirement for major and technology GenEd course HIST 125 (3) Or other arts/humanities GenEd course HUMN 100 (3) Or other arts/humanities GenEd course GEOL 100 (3) Or other 3-credit biological/physical science GenEd course BIOL 101/102 or NSCI 100/101 (4) Or other biological/physical science GenEd course with related lab ECON 203 (3) Related requirement for major and behavioral/social science GenEd course ECON 201 (3) Related requirement for major and behavioral/social science GenEd course SPCH 100 (3) Or other communication, writing, or speech GenEd course WRTG 394 (3) Or other upper-level advanced writing GenEd course CHECKLIST FOR FULFILLMENT OF DEGREE REQUIREMENTS See catalog for overview of all requirements. -

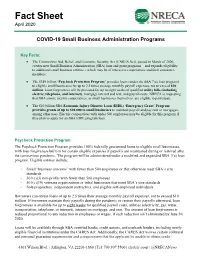

Fact Sheet April 2020

Fact Sheet April 2020 COVID-19 Small Business Administration Programs Key Facts: • The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), passed in March of 2020, creates new Small Business Administration (SBA) loan and grant programs – and expands eligibility to additional small business entities – which may be of interest to cooperatives and their consumer- members. • The $349 billion ‘Paycheck Protection Program’ provides loans (under the SBA 7(a) loan program) to eligible small businesses for up to 2.5 times average monthly payroll expenses, not to exceed $10 million. Loan forgiveness will be provided for up to eight weeks of qualified utility bills (including electric, telephone, and internet), mortgage interest and rent, and payroll costs. NRECA is requesting that SBA ensure electric cooperatives, as small businesses themselves, are eligible to participate. • The $10 billion SBA Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) ‘Emergency Grant’ Program provides grants of up to $10,000 to small businesses to maintain payroll and pay rent or mortgages, among other uses. Electric cooperatives with under 500 employees may be eligible for this program if they plan to apply for an SBA EIDL program loan. Paycheck Protection Program The Paycheck Protection Program provides 100% federally guaranteed loans to eligible small businesses, with loan forgiveness built-in for certain eligible expenses if payrolls are maintained during or restored after the coronavirus pandemic. The program will be administered under a modified and expanded SBA 7(a) loan program. Eligible entities include: - Small “business concerns” with fewer than 500 employees or that otherwise meet SBA’s size standards - 501(c)(3) non-profits with fewer than 500 employees - 501(c)(19) veterans organizations or tribal businesses that meet SBA’s size standards - Sole proprietors, independent contractors, and eligible self-employed individuals Borrowers can obtain loans of up to 2.5 times their average monthly payroll expenses, not to exceed $10 million. -

Business Administration Programs

B: BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION PROGRAMS THE FOLLOWING IS REQUIRED FOR THE ASSOCIATE IN SCIENCE IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION FOR TRANSFER DEGREE: Business Administration (1) Completion of 60 semester units or 90 quarter units that are eligible for transfer to PROGRAM the California State University, including both of the following: (A) The Intersegmental General Education Transfer Curriculum (IGETC)or the (209) 575-6129 California State University General Education - Breadth Requirements. (B) A minimum of 18 semester units or 27 quarter units in a major or area of The Business Administration program provides theoretical and practical courses, emphasis, as determined by the community college district. degrees, certifi cates of achievement, and skills recognition awards in the areas of (2) Obtainment of a minimum grade point average of 2.0 Business Administration, Accounting, Bookkeeping, Business Operations Management, Marketing, Human Resources, Supervisory Management, International Business, Retail Management, Customer Service, and Real Estate. Career opportunities in business include ADTs also require that students must earn a C or better in all courses required for the major or area of emphasis. A "P" (Pass) grade is not an acceptable grade for courses in the major. the fi elds of accounting, fi nance, small business development, human resources, business operations, marketing, and management in retail, service, and manufacturing companies, government agencies, and non-profi t organizations. REQUIRED CORE: (18 UNITS) Students seeking transfer