Revisionism and Diversification in New Religious Movements Edited by Eileen Barker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex and New Religions

Sex and New Religions Oxford Handbooks Online Sex and New Religions Megan Goodwin The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements: Volume II Edited by James R. Lewis and Inga Tøllefsen Print Publication Date: Jun 2016 Subject: Religion, New Religions Online Publication Date: Jul 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190466176.013.22 Abstract and Keywords New religions have historically been sites of sexual experimentation, and popular imaginings of emergent and unconventional religions usually include the assumption that members engage in transgressive sexual practices. It is surprising, then, that so few scholars of new religions have focused on sexuality. In this chapter, I consider the role of sexual practice, sexual allegations, and sexuality studies in the consideration of new religions. I propose that sex both shapes and haunts new religions. Because sexuality studies attends to embodied difference and the social construction of sexual pathology, the field can and should inform theoretically rigorous scholarship of new religious movements. Keywords: Sex, sexuality, gender, heteronormativity, cults, sex abuse, moral panic WE all know what happens in a cult. The word itself carries connotations of sexual intrigue, impropriety, even abuse (Winston 2009). New Religious Movements (NRMs) have historically been sites of sexual experimentation, and popular imaginings of emergent and unconventional religions usually include the assumption that members engage in transgressive sexual practices. It is surprising, then, that so few NRM scholars have focused on sexuality.1 In this chapter, I consider the role of sexual practice, sexual allegations, and sexuality studies in the consideration of NRMs. I propose the following. Sex shapes new religions. NRMs create space for unconventional modes of sexual practices and gender presentations. -

Barker, Eileen. "Denominationalization Or Death

Barker, Eileen. "Denominationalization or Death? Comparing Processes of Change within the Jesus Fellowship Church and the Children of God aka The Family International." The Demise of Religion: How Religions End, Die, or Dissipate. By Michael Stausberg, Stuart A. Wright and Carole M. Cusack. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. 99–118. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350162945.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 18:58 UTC. Copyright © Michael Stausberg, Stuart A. Wright, Carole M. Cusack, and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Denominationalization or Death? Comparing Processes of Change within the Jesus Fellowship Church and the Children of God aka The Family International Eileen Barker This is an account of the apparently impending demise of two new religious movements (NRMs) which were part of the Jesus movement that was spreading across North America and western Europe in the late 1960s. Both movements were evangelical in nature; both had a charismatic preacher as its founder; and both believed from their inception in following the lifestyle of the early Christians as described in the Acts of the Apostles.1 One of the movements began in the small village of Bugbrooke, a few miles southwest of Northampton in the English Midlands; the other began in Huntington Beach, California. -

The Life and Legacy of Sun Myung Moon and The

Summary Report & Reflections ‘The Life and Legacy of SMM and the Unification Movements in Scholarly Perspective’ Faculty of Comparative Study of Religion and Humanism (FVG) Antwerp, Belgium 29-30 May 2017 __________________________________________________________________ Organized by: The European Observatory of Religion and Secularism (Laïcité) in partnership with Faculty of Comparative Study of Religion and Humanism (FVG), CESNUR & CLIMAS (Bordeaux) This is a summary-report and a reflection on the recent conference in Antwerp, Belgium. The text is a compilation of impressions and reflections by Dr. Andrew Wilson, Dr. Mike Mickler, Dan Fefferman, Hugo Veracx, Peter Zoehrer and Catriona Valenta. The number of participants (including scholars & organizers) was around 40: 15 persons belonging to Sanctuary Church, 8 participants from the Preston (H1) group, 8 from FFWPU and 9 neutral (ex-members, scholars, etc.). The conference was devoted almost exclusively to examining the background and development of the schisms that have emerged in the Unification Movement since the death of the founder. DAY ONE The first day was consistent with the conference theme of the „Life and legacy of Sun Myung Moon and Unification Movements“ in a scholarly perspective. Dr. Eileen Barker led off with an excellent keynote address titled "The Unification Church: A Kaleidoscopic History." She looked at the UM as a religious movement, a spiritual movement, a charismatic movement, a messianic movement, a millenarian movement, a utopian movement, a political movement, a financial-business movement, a criminal movement, a sectarian movement, a denominationalizing movement, and a schismatic movement. It was a good introduction to the conference as a whole. Alexa Blonner followed with a very excellent presentation on the UM's antecedents in Neo-Confucian thought and also the ways in which the UM went beyond that heritage. -

Gary Shepherd CV April 2013

CURRICULUM VITA April, 2013 PROFESSIONAL IDENTIFICATION 1. ACADEMIC AFFILIATION Gary Shepherd Oakland University Department of Sociology and Anthropology Professor of Sociology Emeritus 2. EDUCATION Degree Institution Date Field Ph.D. Michigan State University 1976 Sociology M.A. The University of Utah 1971 Sociology B.A. The University of Utah l969 Sociology FACULTY TEACHING APPOINTMENTS 1. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY Part-Time Instructor (Department of Sociology; School of Social Work), 1974-1976. 2. OAKLAND UNIVERSITY Rank and Date of Appointment: Visiting Assistant Professor, 8/15/76 - 8/14/77 Assistant Professor, 8/15/77 Dates of Reappointment: Assistant Professor, 8/15/81 Assistant Professor, 8/15/79 Rank and Date of Promotion: Associate Professor With Tenure, 8/15/83 Full Professor With Tenure, 4/6/95 Professor Emeritus, 9/15/09 Interim Director, The Honors College, 2010-2011 COURSES TAUGHT 1. Introduction to Sociology (SOC 100) 2. Introduction to Social Science Research Methods (SOC 202) 3. Social Statistics (SOC 203) 4. Self and Society (SOC 206) 5. Social Stratification (SOC 301) 6. Sociology of Religion (SOC 305) 7. Sociology of The Family (SOC 335) 8. Moral Socialization (SOC 338) 9. Sociology of New Religious Movements (SOC 392) 10. Sociological Theory (SOC 400) 11. Honors College Freshman Colloquium (HC100) 2 SCHOLARLY ACTIVITIES 1. PUBLISHED BOOKS: Shepherd, Gary and Gordon Shepherd. Binding Heaven and Earth: Patriarchal Blessings in the Prophetic Development of Early Mormonism. The Penn State University Press, 2012. Shepherd, Gordon and Gary Shepherd. Talking with The Children of God: Prophecy and Transformation in a Radical Religious Group. The University of Illinois Press, 2010. -

Nansook Hong

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia Nansook Hong From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is a Korean name; the Main page Korean name Contents family name is Hong. Hangul 홍난숙 Featured content Nansook Hong (born 1966), is Current events Hanja 洪蘭淑 the author of the Random article Revised Romanization Hong Nan-suk autobiography, In the Shadow Donate to Wikipedia McCune–Reischauer Hong Nansuk Wikipedia store of the Moons: My Life in the Reverend Sun Myung Moon's Interaction Family, published in 1998 by Little, Brown and Company. It gave her account Help of her life up to that time, including her marriage to Hyo Jin Moon, the first About Wikipedia son of Unification Church founder and leader Sun Myung Moon and his wife Community portal Hakja Han Moon.[1] Recent changes Contact page Contents [hide] Tools 1 In the Shadow of the Moons What links here 2 Hyo Jin Moon Related changes 3 Notes Upload file 4 References Special pages Permanent link Page information In the Shadow of the Moons [ edit ] Wikidata item Cite this page In the Shadow of the Moons: My Life in the Reverend Sun Myung Moon's Family is a 1998, non-fiction work by Hong and Boston Globe reporter Eileen Print/export McNamara, published by Little, Brown and Company (then owned by Time Create a book Warner). It has been translated into German[2] and French.[3] Download as PDF Author and investigative reporter Peter Maass, writing in the New Yorker Printable version Magazine in 1998, said that Hong's divorce was the Unification Church's Languages "most damaging scandal", and predicted that her then unpublished book 日本語 would be a "tell-all memoir".[4] In October 1998, Hong participated in an Edit links online interview hosted by TIME Magazine, in which she stated: "Rev. -

2018-02-19 the Rod of Iron Controversy

"Why do you call me good?" Jesus answered. "No one is good-except God alone." Mark 10:18 To achieve this, someone on behalf of God must be victorious over Satan, both as an individual and as an adopted son. Moreover, as a child of direct lineage, he must fight with the satanic world and win over it for God. CSG 192 Greetings! In Hyung Jin Nim's sermon on Sunday, he explained that thos e using a rod of iron especially need a sound mind. You never can take back a bullet. If you make a mistake, you are responsible for the consequences. Be slow to anger. That's why it's important to drill and practice. ALWAYS check any weapon to see if it is loaded. It's an inanimate object that needs to be controlled by a responsible person. Free enterprise leads to great wealth. But with wealth comes the danger that it can lead to relativism and corruption. That is why Peace Police Peace Militia training is so important, for developing self-control, humility and learning to relate to people of different classes and backgrounds. Kingdom of the Rod of Iron 5 - February 18, 2018 - Rev. Hyung Jin Moon - Unification Sanctuary, Newfoundland PA In Matthew 19:24, Jesus warned us that " Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God." Be careful not to be a moral posturer or practice self-idolatry. Jesus said no one is good except God. -

Building Partnerships for Peace Based on Interdependence, Mutual Prosperity, and Universal Values

Building Partnerships for Peace based on Interdependence, Mutual Prosperity, and Universal Values Saturday, February 27, 7:30 PM EST, USA (4:30 PM, PST) (Broadcast live from South Korea) https://RallyofHope.us Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon, Co-Founder, Universal Peace Federation Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon is the co-founder of the Universal Peace Federation, established in 2005 with her late husband, Rev. Dr. Sun Myung Moon. Together they have spent six decades creating hundreds of organizations in all sectors of society, both global and local in reach, that are focused on breaking down barriers and bringing people together to establish real examples of peace throughout the world. In August 2020, Dr. Moon launched the Rally of Hope series, working with world leaders to bridge the political and religious spheres while addressing the critical issues of society. A best-selling author, Dr. Moon published her memoir, Mother of Peace, in 2020. She is also the founder of the World Christian Leadership Conference (WCLC), among other notable ventures. Dr. Moon will present the Rally of Hope Founders’ Address. H.E. Muhammadu Buhari, President, Nigeria President of Nigeria since 2015, His Excellency Muhammadu Buhari is a retired Major General of the Nigerian Army with more than five decades of military service. As military Head of State, General Buhari reformed the nation’s economy to rebuild Nigeria’s socio-political and economic systems. With his presidential administration, he has worked to improve Nigeria’s foreign policy, and launched the National Social Investment Program in 2016 to address poverty, unemployment, and increase economic development. -

The Demise of Religion: How Religions End, Die, Or Dissipate

Stausberg, Michael, Stuart A. Wright, and Carole M. Cusack. "Index." The Demise of Religion: How Religions End, Die, or Dissipate. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. 201–206. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 05:57 UTC. Copyright © Michael Stausberg, Stuart A. Wright, Carole M. Cusack, and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Index abuse 9, 19, 72, 76–9, 105, 110–11, 121– atheism 138 32, 157, 161–2. See also violence Aum Shinrikyō 7–8, 17, 22–3, 25, 27, of children 9, 104, 109–11, 115 n. 31, 49–60, 61 n. 6, 62 n. 10–11, 158, 162, 166 166, 187 sexual 9–10, 23, 67, 71, 104, 109–11, Austin, J. L. 43–4 120, 127, 162–3, 166, 169 Australia 24, 32, 157 spiritual 121, 128–32 authoritarianism 121, 123, 155, 170, 177 of weakness (abus de faiblesse) 157, 167–8, 170 Bainbridge, William Sims 13, 22, 57, African American 162. See also 108 nationalism, black bigotry 143 Agonshū 52 birth control 107 Aleph 23, 50, 54–6, 59, 61 n. 8 Bahai 5 America. See United States baptism 99, 101, 148 Amerindian 162 Baptist 32–3, 99–101 Amour et Misericorde 158, 168–70 Barker, Eileen 9, 89–90, 96, 104, 107–8, Amsterdam, Peter 105, 108 177–8 Ancient and Mystic Order of the Rosy Barltrop, Mabel. See Octavia Cross (AMORC) 179 Bedford 83, 89–90, 92 Ancient Egypt 21, 162, 164 Bellah, Robert 91 Anglicanism 8, 94. -

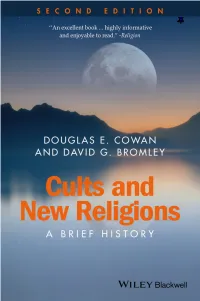

Cults and New Religions: a Brief History

Cults and New Religions WILEY BLACKWELL BRIEF HISTORIES OF RELIGION SERIES This series offers brief, accessible, and lively accounts of key topics within theology and religion. Each volume presents both academic and general readers with a selected history of topics which have had a profound effect on religious and cultural life. The word “history” is, therefore, understood in its broadest cultural and social sense. The volumes are based on serious scholarship but they are written engagingly and in terms readily understood by general readers. Other topics in the series: Published Heaven Alister E. McGrath Heresy G. R. Evans Death Douglas J. Davies Saints Lawrence S. Cunningham Christianity Carter Lindberg Dante Peter S. Hawkins Love Carter Lindberg Christian Mission Dana L. Robert Christian Ethics Michael Banner Jesus W. Barnes Tatum Shinto John Breen and Mark Teeuwen Paul Robert Paul Seesengood Apocalypse Martha Himmelfarb Islam, 2nd edition Tamara Sonn The Reformation Kenneth G. Appold Utopias Howard P. Segal Spirituality, 2nd edition Philip Sheldrake Cults and New Religions, 2nd edition Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley Cults and New Religions A Brief History Second Edition Douglas E. Cowan Renison College, University of Waterloo and David G. Bromley Virignia Commonwealth University This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. (1e, 2008) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. -

Ageing in New Religions: the Varieties of Later Experiences

Eileen Barker Ageing in new religions: the varieties of later experiences Article (Published version) (Refereed) Original citation: Barker, Eileen (2011) Ageing in new religions: the varieties of later experiences. Diskus, 12 . pp. 1-23. ISSN 0967-8948 © 2011 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50871/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2013 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. The Journal of the British Association for the Study of Religions (www.basr.ac.uk) ISSN: 0967-8948 Diskus 12 (2011): 1-23 http://www.basr.ac.uk/diskus/diskus12/Barker.pdf Ageing in New Religions: The Varieties of Later Experiences1 Eileen Barker London School of Economics / Inform [email protected] ABSTRACT In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s and 1980s a wide variety of new religions became visible in the West, attracting young converts who often dropped out of college or gave up their careers to work long hours for the movements with little or no pay. -

World Peace Festival” in the Olympic Sta- Dium in Seoul’S Jamsil District on September 16

INTERVIEW INTERVIEW INTERVIEW Gordon G. Chang DR. Eva Latham Park Young Sun On China’s Demise Corporate Guri Nature, Culture, and Challenge to the Social and Design Project West Responsibility (NCD) 2015 ASIA-PACIFIC www.biztechreport.com Vol. 4, No. 4, 2012 REPORTREPORT Potential of Investment Growing Tension in in Power Sector in India Japanese-Korean Ties Asia-Pacific The Transforming Undergoing Indian Higher a Digital Education Sector TV Boom Samsung’s Business Increasing Model Profile in Your Southeast Career Asia Future of Nuclear Power in Japan Mr. Lee Man-Hee, Founder Pastor Shinchonji Church of Jesus Christ World Ms. Kim Nam-Hee, Chairwoman Peace MANNAM Volunteer Association Festival When Light Meets Light W9,900 | £6.00 | €8.00 `40 | US$8.00 | CN$8.00 230X280.indd 2 2011.9.20 10:16:25 AM 230X280.indd 2 2011.9.20 10:16:25 AM Contents COVCOVERER STOSTOryry Vol. 4, No. 4, 2012 World Peace age 8 p Festival When Light Meets Light, There is Victory specIAL FEATURE gurI CITY page 26 QDr eva Latham& — pageA 12 tim clark — page 24 park Young Sun — page 29 michelle Finn — page 32 Gordon G. chang — page 42 David roodman — page 50 Publisher: MR. LEE DEuK hO By PRIyaNKa ShaRMa Editor-in-Chief: MR. LEE DEuK hO REMEMBRAnce 37 Japanese FIrMS CoNSIDEr MoVING FroM China, EYEING SoUTHEAST ASIA 16 LIVING For THE SAKE oF oTHErS: rEVErEND By DaVID WOO published by: asia-Pacific Business Dr. SUN MYUNG MooN (1920-2012) & Technology Report Co. 38 China’S AUTo MArKET INDUSTrY: By RONKI RaM GroWING DESPITE CHALLENGES registration date: 2009.09.03 registration number: 서올중. -

Rev. Hyung Jin Moon Unification Sanctuary, Newfoundland PA

And from Jesus Christ, who is the faithful witness, and the first begotten of the dead, and the prince of the kings of the earth. Unto him that loved us, and washed us from our sins in his own blood, And hath made us kings and priests unto God and his Father; to him be glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen. Rev 1:5-6 In the beginning of history, Eve fell because she did not become one with God. If she had obeyed God's commandment, even at the cost of her life, and walked the road of death gladly, the fall would not have occurred. Accordingly, today Unification Church women should pledge their lives, hold on to God, and march forward. SMM, Blessing and Ideal Family, Chapter 5: "The Formula Course for Perfection" Greetings! In Sunday's powerful service Hyung Jin Nim discussed how many non- biblical movements are leading people away from God, like the Han Mother saying there is no benefit from studying the Old Testament, the New Testament words of Jesus, and Completed Testament words of True Father (see graphic below). Just like the Israelites who tried to be multi-cultural and were absorbed into the Assyrian culture. The Bible has real-life stories to guide us. If you take the story of God out of this context, the Messiah doesn't mean anything. Or you can portray Christ as a socialist and relativist. Sunday Service - April 7, 2019 - Rev. Hyung Jin Moon Unification Sanctuary, Newfoundland PA It is heartbreaking to report to Unificationists that on Saturday, April 6 in her "Peace Starts with Me" speech in Los Angeles, Hak Ja Han informed the audience that it was "greed" that led the human ancestors to fall (see video).