Giant Slalom by Georg Capaul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometry and Running of the Alpine Skiing Fis World Cup

GEOMETRY AND RUNNING OF THE ALPINE SKI FIS WORLD CUP GIANT SLALOM PART ONE - GEOMETRY Wlodzimierz S. Erdmann, Andrzej Suchanowski and Piotr Aschenbrenner Jedrzej Sniadecki University School of Physical Education, Gdansk, Poland The aim of this paper is the presentation of the geometry of the alpine ski giant slalom at the highest world level in order to calculate the obtained time by videorecording velocity and acceleration of running. KEY WORDS: alpine skiing, giant slalom, fis world cup, geometry INTRODUCTION: In alpine skiing the role of a coach is a difficult one. This is due in part, to the fact that during the competition he would be unable to observe the athlete for the entire track, regardless of the position he chose, because of the extensive terrain. Before the competition the organizing committee provides data only on general description of the course, i.e. the length of the slope (measured usually without snow) and few data on the incline of the slope. Unfortunately, no data on geometry of gates is supplied to the coaches. During the competition the time of running of the entire course and of one or two segments of the course are displayed. These data do not provide sufficient information with which to evaluate adequately an athlete’s performance on the course. Possession of detailed data on the geometry of the poles setting and on the time of the running between them would allow the coach to more accurately assess the performance of the skier on the course, i. e. what velocity and acceleration he had achieved between the gates. -

Maze Storms to Giant Slalom Win

Warner puts Aussies on top as Test turns feisty 43 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2014 SATURDAY, SportsSports ARE: Tina Maze of Slovenia competes on her way to win an alpine ski, womenís World Cup giant slalom. —AP Maze storms to giant slalom win SWEDEN: Olympic champion Tina Maze consoli- tal globe last season, has 303. same venue and a women’s competition in on the Olympia course. Dopfer was .57 seconds dated her overall World Cup lead on Friday American superstar Lindsey Vonn sits sixth Courcheval, both slated for this weekend, had behind and American skier Ted Ligety trailed by when she produced a stunning second giant overall on 212pts thanks to her stunning Lake already been called off due to mild tempera- .81. Hirscher, who won the season-opening slalom run to clinch an impressive victory. Louise win last weekend. Maze, who was the tures and a lack of snow. giant slalom in Soelden, Austria, was looking to The Slovenian had trailed in seventh from Alpine skiing star at the Sochi Games after win- But the FIS said the women’s disciplines become the fifth Austrian to reach 25 World Cup the first leg earlier in the day in Are, but finished ning both the giant slalom and the downhill, would go ahead at Val d’Isere while a decision is wins. The race was moved from Val d’Isere to with a combined time of 2 minutes 23.84 sec- claimed she had been tired on the early run, but yet to be made on the men’s super-G and down- northern Sweden because of a lack of snow in onds, 0.2sec ahead of Sweden’s Sarah Hector woke up in time to save the day. -

SELECTION CRITERIA 2020 FIS SNOWBOARD JUNIOR WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Parallel Giant Slalom/Parallel Slalom – Lachtal, AUT March 30 – April 1 Snowboardcross – St

SELECTION CRITERIA 2020 FIS SNOWBOARD JUNIOR WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Parallel Giant Slalom/Parallel Slalom – Lachtal, AUT March 30 – April 1 SnowboarDcross – St. Lary, FRA March 23-25 Slopestyle/Big Air – TBD Halfpipe – TBD 1. PHILOSOPHY: U.S. Ski & SnowboarD will select only the most qualifieD athletes with the greatest opportunity for winning meDals at the 2020 FIS Junior WorlD Championships. U.S. SKI & SNOWBOARD will consider for selection only those U.S. SKI & SNOWBOARD members in good standing who have a valid U.S. passport, an active U.S. coded FIS license, and who meet FIS minimum eligibility standards. 2. QUOTAS: U.S. SKI & SNOWBOARD may select any number of athletes up to the total number of start quotas as determined by FIS, with a maximum number of athletes up to six (6) per gender per discipline for Parallel Giant Slalom/Parallel Slalom (PGS/PSL), Halfpipe (HP), Slopestyle/Big Air (SS/BA), SnowboarDcross (SBX). 3. ELIGIBILITY: The age limit for the 2020 FIS SnowboarD Junior WorlD Championships will be by year of birth: from 2000-2004 for PGS/PSL and SBX events and from 2002-2006 for HP and SS/BA. 4. NAMING OF THE PARTICIPANTS: The U.S. SnowboarD FIS Junior WorlD athletes will be nameD two (2) weeks prior to the first day of the respective Junior World Championship event, once the date is set by FIS. They will be announced at the U.S. Ski and Snowboard offices and posted on the U.S. Ski & SnowboarD website. 5. APPLICABLE RULES: All qualifying competitions are governeD by the international feDeration rules of competition. -

Training and Periodization for Snowboard Cross, Parallel Slalom and Parallel Giant Slalom

TRAINING AND PERIODIZATION FOR SNOWBOARD CROSS, PARALLEL SLALOM AND PARALLEL GIANT SLALOM Ilona Ruotsalainen Science of Sport Coaching and Fitness Testing Coaching Seminar LBIA016 Spring 2012 Department of Biology of Physical Activity University of Jyväskylä Supervisor: Antti Mero ABSTRACT Ruotsalainen, Ilona 2012. Training and periodization for snowboard cross, parallel slalom and parallel giant slalom. Science of Sport Coaching and Fitness Testing. Coaching Seminar, LBIA016, Department of Biology of Physical Activity, Univer- sity of Jyväskylä, 42 pages. Snowboarding is a popular recreational sport, but it is also an elite sport. Snowboarding has been an Olympic sport since 1998. There will be five different snowboarding disci- plines competed in Winter Olympics in Sochi 2014 (half-pipe, parallel giant slalom, parallel slalom, snowboard cross and slopestyle). Most of the snowboard cross and par- allel event competitions are organized by International Ski Federation (FIS). FIS also organizes the World Cup and every second year Snowboard World Championships. Snowboarding environment is challenging. Riders are frequently exposed to training in cold environments and at high altitudes. Because snowboarding is a technical sport snowboarders spend extensive time on-snow training. Apart from that elite snowboard- ers need to have a good physical fitness. Snowboarders experiences high ground reac- tion forces (McAlpine 2010). They also need to have good aerobic fitness, anaerobic capacity as well as good balance and power production capacity (Bakken et al. 2011; Bosco 1997; Creswell & Mitchell 2009; Neumayer et al. 2003; Platzer at al. 2009; Szmedra et al. 2001; Veicsteinas et al. 1984). Also, coaches have to pay attention to injury prevention because snowboarders, especially snowboard cross riders, have high risk of injuries (Flørenes et al. -

Winter Press Kit 2019-2020

WINTER PRESS KIT 2019-2020 PRESS CONTACT TAYLOR PRATHER [email protected] 970-968-2318 EXT. 38849 OVERVIEW Located 75 miles west of Denver, Colo. in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, Copper Mountain Resort is the preferred mountain destination with an adventurous vibe that represents the best of Colorado. MORE THAN JUST A SKI RESORT, COPPER MOUNTAIN Three pedestrian village areas provide a vibrant atmosphere with lodging, retail, restaurants, bars and TAKES CENTER STAGE AS family activities. On the mountain, Copper’s naturally- THE ULTIMATE VENUE FOR divided terrain offers world-class skiing and riding for ELITE LEVEL TRAINING AND all, including elite level training and competition. COMPETITION IN COLORADO - GIVING GUESTS THE Copper Mountain Resort boasts curated events year- OPPORTUNITY TO SKI AND round and is home to Woodward Copper – a lifestyle RIDE ALONGSIDE WORLD- and action sports hub which includes high-grade on- CLASS ATHLETES. snow training venues and a 19,400 sq. ft. indoor facility. Copper Mountain is part of the POWDR Adventure Lifestyle Co. portfolio. BY THE C o p p e r M o u n t a i n i s c o n v e n i e n t l y l o c a t e d o f f o f I - 7 0 a t E x i t 1 9 5 . t h e r e s o r t i s NUMBERS a p p r o x i m a t e l y 1 0 0 m i l e s ( 2 h o u r s ) f r o m D e n v e r I n t e r n a t i o n a l A i r p o r t a n d 5 5 m i l e s ( 1 h o u r ) f r o m E a g l e C o u n t y R e g i o n a l A i r p o r t . -

Dynamics of Carving Runs in Alpine Skiing. II.Centrifugal Pendulum with a Retractable Leg

Dynamics of carving runs in alpine skiing. II.Centrifugal pendulum with a retractable leg. Serguei S. Komissarov Department of Applied Mathematics The University of Leeds Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK Abstract In this paper we present an advanced model of centrifugal pendulum where its length is allowed to vary during swinging. This modification accounts for flexion and extension of skier’s legs when turning. We focus entirely on the case where the pendulum leg shortens near the vertical position, which corresponds to the most popular technique for the transition between carving turns in ski racing, and study the effect of this action on the kinematics and dynamics of these turns. In partic- ular, we find that leg flexion on approach to the summit point is a very efficient way of preserving the contact between skis and snow. The up and down motion of the skier centre of mass can also have significant effect of the peak ground reaction force experienced by skiers, partic- ularly at high inclination angles. Minimisation of this motion allows a noticeable reduction of this force and hence of the risk of injury. We make a detailed comparison between the model and the results of a field study of slalom turns and find a very good agreement. This suggests that the pendulum model is a useful mathematical tool for analysing the dynamics of skiing. Keywords: alpine skiing, modelling, balance/stability, performance Introduction The skiing of expert skiers is characterised by smooth and rhythmic moves which are very reminiscent of a pendulum or metronome. This analogy invites mathematical modelling of skiing based on the pendulum action, which can be traced back to the pioneering work by Morawski (1973). -

Performance Parameters in Competitive Alpine Skiing Disciplines of Slalom, Giant Slalom and Super-Giant Slalom

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Performance Parameters in Competitive Alpine Skiing Disciplines of Slalom, Giant Slalom and Super-Giant Slalom Lidia B. Alejo 1,2 , Jaime Gil-Cabrera 1,3, Almudena Montalvo-Pérez 1 , David Barranco-Gil 1 , Jaime Hortal-Fondón 1 and Archit Navandar 1,* 1 Faculty of Sports Sciences, Universidad Europea de Madrid, C/Tajo, s/n, 28670 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (L.B.A.); [email protected] (J.G.-C.); [email protected] (A.M.-P.); [email protected] (D.B.-G.); [email protected] (J.H.-F.) 2 Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (imas12), 28041 Madrid, Spain 3 Royal Spanish Winter Sports Federation, 28703 San Sebastian de los Reyes, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The objective of this study was to describe the kinematic patterns and impacts in male and female skiers in the super-giant slalom, giant slalom and slalom disciplines of an international alpine skiing competition using a portable Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) technology device. Fifteen skiers (males, n = 9, females, n = 6) volunteered to participate in this study. Data acquisition was carried out using a wireless inertial measurement device (WIMUTM PRO: hybrid location system GNSS at 18 Hz with a precision locator UltraWideband UWD (<10 cm) and 3D accelerometers 1000 Hz) where distances covered in different speed and acceleration thresholds and Citation: B. Alejo, L.; Gil-Cabrera, J.; impacts above 5g were recorded in each of the disciplines. Male and female alpine skiers showed Montalvo-Pérez, A.; Barranco-Gil, D.; different physical parameters and impacts even though they competed in the same courses in the Hortal-Fondón, J.; Navandar, A. -

Section B (A Technical Understanding of Snowboarding)

B/01 Section b - A Technical Understanding of Snowboarding 6 In this chapter we will explore... How snowboarders can alter their path down the The Snowboard mountain by making turns of different shapes and sizes. Alongside this, we will look at the different Turn phases of the turn which are particularly useful Turn Size and Shape when communicating the sequence of events throughout a turn to your Turn phases students. We will also explain the variety of turn types that can be used and Turn types consider the forces that impact the turn. Turn forces CHAPTER 6 / THE SNOWBOARD TURN B/02 Turn Size and Shape Put simply, the longer the board spends in the fall line or the more gradually a rider applies movements, the larger the turn becomes. When we define the size of the turn we consider the length and radius of the arc: small, medium or large. The size of your turn will vary depending on terrain, snow conditions and the type of turn you choose to make. SMALL MEDIUM LARGE A rider’s rate of descent down the mountain is controlled mainly by the shape of their turns relative to the fall line. The shape of these turns can be described as open (unfinished) and closed (finished). A closed turn is where the rider completes the turn across the hill, steering the snowboard perpendicular to the fall line. This type of turn will easily allow the rider to control both their forward momentum and rate of descent. Closed turns are used on steeper pitches, or firmer snow conditions, to keep forward momentum down. -

Referee – Alpine Study Guide

REFEREE – ALPINE 2018-2019 STUDY GUIDE This Study Guide is intended as an educational and review aid for individuals interested in alpine officiating. Downloading, printing and reading the Study Guide must not be substituted for actual attendance at a U.S. Ski & Snowboard-approved Clinic or used as a replacement for actual instruction at any U.S. Ski & Snowboard-approved Clinic. REFERENCE PUBLICATIONS: 1. U.S. Ski & Snowboard Alpine Competition Regulations (ACR) 2. ACR Precisions, if published 2. ICR of the FIS, Online Edition 3. ICR Precisions, if published 4. U.S. Ski & Snowboard Alpine Officials' Manual (AOM) *NOTE: ACR mirrors, when possible, ICR numbering. U.S. Ski & Snowboard exceptions have a “U” preceding the rule number; the “U” is a part of the number. CERTIFICATION EXAMINATION: Referee Certification Examination will be available at U.S. Ski & Snowboard-approved Alpine Officials’ Clinics. Allowed time limit is 2.5 hours. The examination is open book and, unless an exception is granted by the respective AO Chair, it must be administered only at scheduled Clinics. It is NOT A TAKE HOME EXAM! Allowing use of computers in order to complete calculations or “search” rule books is strongly discouraged; the only items that may be carried into the examination are pencils, calculators, rule books and continuing education materials. Completed examinations must be retained by the Clinic examiners; they are not returned to the individuals taking them. Please refer to Region/Division/State publications for schedules. The Study Guide is not intended as a replacement for taking notes for use during an open-book examination at any U.S. -

Page 1 of 11 Glossary of Ski Terms by Skis.Com 9/6/2015

Glossary of Ski Terms by Skis.com Page 1 of 11 Home > Ski-O-Pedia > Glossary of Ski Terms Glossary of Ski Terms By Steve Kopitz 12/18/2012 Skiing and snowboarding are two of the greatest winter sports on the planet, and like anything else in this world the two sports have certain terms and jargon that can be confusing without a bit of definition. Below you will find a number of terms/phrases used in skiing and snowboarding to refer to products, clothing, and the sports of skiing and snowboarding in general. We have provided a brief definition to help clear up any confusion or questions you may have on these terms/phrases. A ABS Sidewall: Industry term for a type of edge construction on skis and snowboards using high quality ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) plastic. All-Mountain Ski: A large percentage of Alpine skis fall into this category. All-Mountain skis are designed to perform in all types of snow conditions and at most speeds. Other names for this style of ski include Mid- Fat skis, All-Purpose skis, and the One-ski Quiver. Alpine Skiing: Downhill skiing, as opposed to Nordic Skiing. Après-Ski: The day’s over – time for drinks and swapping war stories from the slopes. Audio Helmet: A helmet wired with speakers that allows you to listen to music while skiing. Avalanche Beacon: A safety device worn by skiers, snowboarders, and others in case an avalanche traps them. The beacon transmits a signal (typically at the international standard frequency of 457khz) that rescuers can use to locate a buried person. -

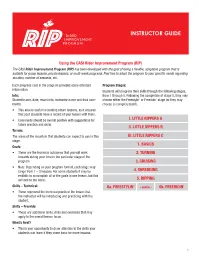

Instructor Guide

INSTRUCTOR GUIDE Using the CASI Rider Improvement Program (RIP) The CASI Rider Improvement Program (RIP) has been developed with the goal of being a flexible, adaptable program that is suitable for group lessons, private lessons, or multi-week programs. Feel free to adapt the program to your specific needs regarding duration, number of sessions, etc. Each progress card in the program provides some standard Program Stages: information: Students will progress their skills through the following stages, Info: from 1 through 5. Following the completion of stage 5, they may Student name, date, resort info, instructor name and final com- choose either the Freestylin’ or Freeridin’ stage (or they may ments: choose to complete both!). • This area is useful in creating return lessons, as it ensures that your students have a record of your lesson with them. • Comments should be overall positive with suggestions for I. LITTLE RIPPERS A future practice and skills. II. LITTLE RIPPERS B Terrain: The areas of the mountain that students can expect to use in this III. LITTLE RIPPERS C stage. 1. BASICS Goals: • These are the technical outcomes that you will work 2. TURNING towards during your time in the particular stage of the program. 3. CRUISING • Note: Depending on your program format, each stage may range from 1 – 3 lessons. For some students it may be 4. SHREDDING realistic to accomplish all of the goals in one lesson, but this will not be the norm. 5. RIPPING Skills – Technical: 6a. FREESTYLIN’ - and/or - 6b. FREERIDIN’ • These represent the technical points of the lesson that the instructor will be introducing and practicing with the student. -

The 4 Edges of the Snowboard

2016 ISSUE 1 The Official Publication of the PSIA-AASI Central Division FLEXING ;) SNOWBOARD UPDATE | WHAT’S NEW IN EDUCATION | SNOWSPORTS DIRECTORS UPDATE | THE 4 EDGES OF A SNOWBOARD The “4 Edges” of a Snowboard By Chuck Roberts n the 1980’s, when snowboarding at most ski resorts was in its infancy, snowboards resembled stiff planks with little flexibility. Figure 1 is a photo of a 1987 Burton V-Tail, a stiff board with a running surface that resembled a V-bottom fishing boat. It also Ihad a location for a skeg (similar to a surf board) to aid when riding in powder. It appeared to work well in powder but had its limitations on groomed slopes. Turning the board involved unweighting and upper body rotation, resulting in skidded turns on groomed slopes. There was virtually no way to torsionally flex the board (torsional flex refers to the design features of a snowboard which allows it to twist along the longitudinal axis of the board), Figure 2). Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 1987 Burton V-Tail “Cruiser” Torsional flex 1991 K2 TX “Gyrator” Modern twin tip snowboard Snowboards evolved into more flexible structures in the Likewise, the leading toe edge of the snowboard is engaged in early 1990’s as shown by the Gyrator in Figure 3. There was Figure 5C and the trailing toe edge is engaged in Figure 5D. some torsional flexibility but the narrow stance (rider’s feet close together) made it difficult to torsionally flex the board. The torsional flexing of the board when turning is performed Despite this, snowboarders discovered that torsionally flexing with the lower body and virtually no upper body influence, the board aided in turning.