Plans, Takes, and Mis-Takes • Klemp, Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 NEA Jazz Masters 2015 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT for the ARTS

2015 NEA Jazz Masters 2015 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2015 Fellows Carla Bley George Coleman Charles Lloyd Joe Segal NEA Jazz Masters 2015 Contents Introduction ..............................................................................1 A Brief History of the Program ................................................2 Program Overview ...................................................................5 2015 NEA Jazz Masters............................................................7 Carla Bley .......................................................................................8 George Coleman............................................................................9 Charles Lloyd ...............................................................................10 Joe Segal ......................................................................................11 NEA Jazz Masters, 1982–2015..............................................12 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony ...................................14 Pianist Jason Moran and guitarist Bill Frisell perform 2014 NEA Jazz Master Keith Jarrett’s “Memories of Tomorrow” at the 2014 awards concert. Photo by Michael G. Stewart The NEA is committed to preserving the legacy of jazz not just for this ”generation, but for future generations as well. ” IV NEA Jazz Masters 2015 IT IS MY PLEASURE to introduce the 2015 class of NEA Jazz Masters. The NEA Jazz Masters awards—the nation’s highest recognition of jazz in America—are given to those who have reached the pinnacle of their art: musicians -

Booking Agency Info

Kristin Asbjørnsen www.kristinsong.com Singer and songwriter Kristin Asbjørnsen is one of the most distinguished artists on the vibrating extended music scene in Europe. During the last decade, she has received overwhelming international response among critics and public alike for her unique musical expression. 2018 saw the release of Kristin’s Traces Of You. Based on her assured melodic flair and poetic lyrics, Kristin has on this critically acclaimed album explored new fields of music. Vocals, kora and guitars are woven creatively into a meditative and warm vibration, showing traces of West African music, lullabyes and Nordic contemporary jazz. Lyrical African ornaments unite in a playful dialogue with a sonorous guitar universe. Kristin sings in moving chorus with the Gambian griot Suntou Susso, using excerpts of her poems translated into Mandinka language. During 2019 Kristin will be touring in Europe in trio with the kora player Suntou Susso and guitarist Olav Torget, performing songs from Traces Of You, as well as songs from her afro-american spirituals repertoire. Kristin is well known for her great live-performances and she is always touring with extraordinary musicians. The Norwegian singer has featured on a number of album releases, as well as a series of tours and festival performances in Europe. Her previous solo albums I’ll meet you in the morning (2013), The night shines like the day (2009) and Wayfaring stranger (2006) were released across Europe via Emarcy/Universal. Wayfaring stranger sold to Platinum in Norway. Kristin made the score for the movie Factotum (Bukowski/Bent Hamer) in 2005. Kristin collaborates with the jazz pianist Tord Gustavsen (ECM). -

Curriculum Vitae

curriculum vitae Kjetil Traavik Møster musiker Skanselien 15 5031 Bergen mob. (+47) 90525892 e-post: [email protected] web: www.moester.no medlem av Gramart, Norsk Jazzforum f. 17/06/76 Bergen, Norge. UTDANNELSE: 2006-2012: Master i utøving jazz/improvisasjon, Norges Musikkhøgskole 1998-2002: Cand. mag. fra NTNU, Musikkonservatoriet i Trondheim, jazzlinja 3-års utøvende musikerutdanning (fordelt på 4 år) 1-års praktisk-pedagogisk utdanning (fordelt på to år) 1996-1997: Musikk grunnfag med etnomusikologi fordypning, NTNU, Universitetet i Trondheim 1995-1996: Sund Folkehøgskole, jazzlinga Annen utdannelse Examen artium, musikklinja, Langhaugen Skole 1995 ARBEID SOM MUSIKER: Har arbeidet som utøvende musiker siden år 2000, og er involvert i diverse prosjekter, bl.a. følgende: - Møster! (startet sommeren 2010) med Ståle Storløkken – orgel/keyboards, Nikolai Eilertsen – el.bass, Kenneth Kapstad – trommer. CD-utgivelse 2013, 2014, 2015 - Møster/Edwards/Knedal Andersen Friimprovisasjonstrio med John Edwards og Dag Erik Knedal Andersen, jevnlig turnéring fra høsten 2013 - Kjetil Møster med BIT20 Ensemble Skrev og fremførte et 30 minutters stykke for 16 stemmer pluss seg selv som solist for BIT20 Ensemble våren 2013 - Kjetil Møster Solo (Kongsberg Jazzfestival 2005, Soddjazz 2006, konserter i Norge 2004, 2005, 2006, 2010, 2011, Moldejazz 2011, turné i Skandinavia 2011, CD-utgivelse 2011) - The Heat Death Friimprovisasjonstrio med Martin Kuchen, Mats Äleklint, Ola Høyer og Dag Erik Knedal Andersen. Turnéring fra 2012, planlagt CD-utgivelse på portugisiske Clean Feed november 2015. - Kjetil Møster Sextet (startet sommeren 2006 i forbindelse med tildelingen av IJFO Jazz Talent Award. Inkluderer Anders Hana, gitar, Per Zanussi og Ingebrigt Håker Flaten, el. og kontrabass, Kjell Nordeson og Morten J. -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, September 2010

Report of the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, September 2010 1 Report of the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, 24 – 26 September 2010 Reporters: Madli-Liis Parts and Martel Ollerenshaw Index General Introduction by President Annamaija Saarela 3 Welcome & Introductions 4 EJN panel debate – Is Jazz now Global or Local? 5 European Music Council 7 Small group sessions and discussion groups 9 Friday 24 September 2010: EJN Research project EJN Jazz & Tourism Project Exchange Staff Small group sessions – proposals from members for artistic projects 14 Saturday 25 September 2010: Take Five EJN Jazz Award for Creative Programming 12 points! Engaging with communities The European economic situation and the future of EJN Jazz on Stage: Jazz rocks Jazz at rock venues in the Netherlands Mediawave Presentation – A Cooperative Workshop The extended possibilities of showcases at jazzahead! 2011 European Jazz Media at the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 26 Jazz.X – International Jazz Media Exchange Project European Jazz Media Group Meeting Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 2010 28 Extraordinary General Assembly Session Annual General Assembly Session Europe Jazz Network welcomes its new members 32 What happened, when and where 33 The Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 2010 – Programme EJN General Assembly 2010 Participants 36 EJN Members at the time of the General Assembly 2010 in Istanbul 39 2 General Introduction by President Annamaija Saarela Dear EJN colleagues it is my pleasure to work for the Europe Jazz Network as president for the year until the 2011 General Assembly in Tallinn. I’ve been a member of EJN since 2003 and deeply understand the importance of our network as an advocate for jazz in Europe. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

Formatting Bios Program Booklet__11-2 ANCHORED EH

FEED THE FIRE A Cyber Symposium in Honor of Geri Allen Thursday, 5 November 2020, 9:30 am–5:30 pm EST An online event free and open to the public Registration requested at http://bit.ly/GeriAllen Keynote with Terri Lyne Carrington, Angela Davis, and Gina Dent, moderated by Farah Jasmine Griffin Poetry reading by Fred Moten | Solo piano performance by Courtney Bryan Geri Allen, Wright Museum of African American History, Detroit, 2011; © Barbara Weinberg Barefield Department of Music Jazz Studies Program Columbia University: Center for Jazz Studies; Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality; Departments of Music and English & Comparative Literature Barnard College: Barnard Center for Research on Women; Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; Department of Africana Studies University of Pittsburgh: Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program; Humanities Center GERI ANTOINETTE ALLEN was born on June 12, 1957. She began playing the piano at the age of seven. As a child, she studied classical music with Patricia Wilhelm, who also nourished her interests in jazz. Her music studies continued through high school, Detroit’s legendary Cass Tech, where she studied with trumpet player Marcus Belgrave; and then at Howard University, where she studied with John Malachi, at the same time taking private lessons from Kenny Barron. In 1979, she earned one of the first BAs in Jazz Studies at Howard. She completed an MA in Ethnomusicology in 1983 at University of Pittsburgh, where she studied with Nathan Davis. When Davis retired in 2013, she succeeded him as Director of Jazz Studies, after teaching at Howard, the New England © Barbara Weinberg Barefield Conservatory, and the University of Michigan. -

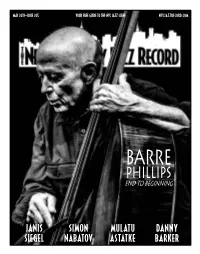

PHILLIPS End to BEGINNING

MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 YOUR FREE guide TO tHe NYC JAZZ sCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BARRE PHILLIPS END TO BEGINNING janis simon mulatu danny siegel nabatov astatke barker Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@nigHt 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : janis siegel 6 by jim motavalli [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist Feature : simon nabatov 7 by john sharpe [email protected] General Inquiries: on The Cover : barre pHillips 8 by andrey henkin [email protected] Advertising: enCore : mulatu astatke 10 by mike cobb [email protected] Calendar: lest we Forget : danny barker 10 by john pietaro [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotligHt : pfMENTUM 11 by robert bush [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or obituaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] Cd reviews 14 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, misCellany 33 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, event Calendar Tom Greenland, George Grella, 34 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mike Cobb, Pierre Crépon, George Kanzler, Steven Loewy, Franz Matzner, If jazz is inherently, wonderfully, about uncertainty, about where that next note is going to Annie Murnighan, Eric Wendell come from and how it will interact with all that happening around it, the same can be said for a career in jazz. -

March April 2006

march/april 2006 issue 280 free jazz now in our 32nd year &blues report www.jazz-blues.com Jason Moran and The Bandwagon Randy Weston Yellowjackets Diane Schuur PLUS...Regina Carter, Bela Fleck & the Flecktones, Manhattan Transfer, Mulgrew Miller, Rebirth Brass Band...Jazz Meets Hip-Hop, Jazz Brunch & more... Get The Scoop...INSIDE! Published by Martin Wahl Communications Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Layout & Design Bill Wahl Operations Jim Martin Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, JazzFest Time is Here Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Festival is Expanding to Year-Round Live Jazz Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane Verh and Ron Weinstock. For close to three decades now, mance by the Manhattan Transfer Jazz & Blues Report has featured will be held at the Ohio Theatre on Check out our new, updated web the Tri-C JazzFest in our issue at page. Now you can search for CD Saturday, April 22. Tri-C JazzFest Reviews by artists, Titles, Record this time every year. Once again, we Cleveland officially kicks off on Labels or JBR Writers. Twelve years are happy to announce yet another Wednesday April 26 at 5 p.m. with a of reviews are up and we’ll be going edition of this premier jazz festival, New Orleans-style “second line” pa- all the way back to 1974! and their expansion to year-round rade, complete with fans, admirers jazz. and festival revelers. Leading the Tri- Now in its 27th year, Tri-C Address all Correspondence to.... C JazzFest Second Line is the Re- Jazz & Blues Report JazzFest Cleveland has been a dy- birth Brass Band, who will end the 19885 Detroit Road # 320 namic force in cultivating the next procession at the House of Blues for Rocky River, Ohio 44116 generation of jazz music lovers a swinging party with The Tri-C Jazz Main Office ..... -

Piano Bass (Upright And/Or Electric)

January 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 1 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin Tolleson; Philadelphia: David Adler, Shaun Brady, Eric Fine; San Francisco: Mars Breslow, Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Yoshi Kato; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Belgium: Jos Knaepen; Canada: Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan Persson; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Brian Priestley; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama; Portugal: Antonio Rubio; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Maria Schneider's Forms

Maria Schneider’s Forms Norms and Deviations in a Contemporary Jazz Corpus Ben Geyer Abstract This study assesses twenty-five works by contemporary jazz composer Maria Schneider, tracking her compositional tendencies, identifying areas of continuity with the big-band arranging tradition, and cap- turing developments and idiosyncrasies apparent in her music. Schneider most often modifies the prototypical big-band arrangement by merging the solo section with the ensemble feature, resulting in a trademark “Solo- Recapitulation trajectory,” which creates a deep-level structure comprising three “Spaces.” “Space division criteria” capture how broad expectations for jazz performance affect listeners’ experiences of Schneider’s compositions. Spaces often comprise more than one “section,” a formal unit at a shallower structural level; the Space division criteria differentiate sectional divisions internal to a single Space from divisions at the boundaries between Spaces. An overview of the corpus data summarizes the sectional makeup of each of the twenty-two normative pieces. Formal and hermeneutical accounts of three deviational pieces demon- strate the flexibility and expressive potential of the system. A retrofit of the formal framework onto thirteen notable big-band arrangements by Schneider’s contemporaries and direct predecessors shows that the Solo- Recapitulation trajectory does not appear in these pieces, suggesting that Schneider may have pioneered the approach. Keywords jazz, Maria Schneider, form, corpus Maria Schneider (b. 1960) stands out as perhaps the most prominent com- poser and bandleader for jazz big band in her generation.1 While many aspects of her compositional technique are notable, Schneider’s formal con- trol is especially salient (Heyer 2007; Martin 2003; McKinney 2008; Stewart 2007), particularly in the context of formal limitations that some writers have perceived in prior large-form compositions for jazz big-band instrumentation. -

MIKE MAINIERI James Lewis Billy Kaye Don Shirley

APRIl 2019—ISSUE 204 YOUR FREE GUIdE To ThE NyC jAZZ sCENE NyCjAZZRECoRd.CoM TONY ASTORIABENNETT IS BORN james MIKE brandon bIlly doN MAINIERI lEwIs kayE shirlEy Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIl 2019—ISSUE 204 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NGEw york@NI hT 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : MIKE MAINIERI 6 by jim motavalli [email protected] Andrey Henkin: A rtisT FEATURE : jAMEs bRANdoN lEwIs 7 by john pietaro [email protected] General Inquiries: On ThE Cover : ToNy bENNETT 8 by andrew vélez [email protected] Advertising: E ncore : bIlly KAyE 10 by russ musto [email protected] Calendar: LeE sT w Forget : doN shIRlEy 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: lAbEl SpoTlighT : driff 11 by eric wendell [email protected] VOXNEws by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or obituaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] Cd REviews 14 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, MIscellany 35 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event CAlendar Tom Greenland, George Grella, 36 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew