ARTISTS in the ARCHIVE Taylor & Francis Taylor & Francis Group Http:/Taylorandfrancis.Com ARTISTS in the ARCHIVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPILL Study Room Guide

Study Room Guide SPILL STUDY BOXES November 2012 In 2012 SPILL Festival of Performance, Ipswich invited the Agency to create a special pop-up version of the Study Room for the SPILL Study Café. For the Study Café the Agency curated a selection of 20 Study Boxes each containing a range of hand picked DVDs, books and other materials around specific themes that we believed would inspire, excite and intrigue artists and audiences attending the Festival in Ipswich. The Study Boxes reflected the work of a huge range of UK and international artists and represent a diversity of themes including issues of identity politics in performance, the explicit body in performance, large scale performance, sound and music in performance, activism and performance, ritual and magic, large scale performance, strange theatre, life long performances, participatory performance, critical writing, non Western performance, do it yourself, trash performance, and many more. Each Study Box contained between four and eight items and could be used for a quick browse or for a day-long study. “Completely brilliant.” (Andy Field, Forest Fringe) “The openness and democracy of the Study Café is essential in a festival where questions of access are so present. It illustrates the need to offer the work of artists up for wider consumption rather than limited to the tight circle of those in the know. Proximity cuts both ways, and as a group of performance makers, it falls to artists, writers and enthusiasts to collapse these referential gaps between audiences. As funding shrinks and organisations falter, the ability to bring those without any history of performance in, to speak to issues outside of the intellectual concerns of Live Art becomes essential for the survival of the form and any community around it. -

To Make Time Ppear

! ∀#∃∃! ! % &#∋() ! ∗+,−(! . / 0 ! 1 22 !30!!2&∃#∀2 0 0 1 0 0 ∋ ) 0 1 3 0 3 ! 4 0 4 0 0 4 0 1 56 3 7! 4 0 00 ! 1 0 0 03 3 ! 4 4 4 8 0 0 9 : 4 7 1 1 0 7 7 4 3 0 2 ! 22 ,3!30 !! 8 0 1, ;30!! Art Journal The mission of Art Journal, founded in %)'%, is to provide a forum for In This Issue Vol. !", no. # scholarship and visual exploration in the visual arts; to be a unique voice in the Fall $"%% fi eld as a peer-reviewed, professionally mediated forum for the arts; to operate ! Katy Siegel in the spaces between commercial publishing, academic presses, and artist Title TKTK Editor in Chief Katy Siegel presses; to be pedagogically useful by making links between theoretical issues Editor Designate Lane Relyea and their use in teaching at the college and university levels; to explore rela- Reviews Editor Howard Singerman tionships among diverse forms of art practice and production, as well as among Senior Editor Joe Hannan art making, art history, visual studies, theory, and criticism; to give voice and Centennial Essay Editorial Assistant Mara Hoberman publication opportunity to artists, art historians, and other writers in the arts; Digital Fellow Katherine Behar to be responsive to issues of the moment in the arts, both nationally and glob- " Krista Thompson Designer Katy Homans ally; to focus on topics related to twentieth- and twenty-fi rst-century concerns; A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States Production Nerissa Vales to promote dialogue and debate. -

How We Talk About the Work Is the Work: Performing Critical Writing

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2018.1464751 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Schmidt, T. (2018). How We Talk About The Work Is The Work: Performing Critical Writing. PERFORMANCE RESEARCH , 23(2), 37-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2018.1464751 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Ron Athey Gifts of the Spirit: Automatic Writing Automatic Writing Workshop July 23-27, 2013 for Participants Only, See Enclosed Call for Applicants

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, July 2013 Contact: Lia Gangitano [email protected] 646.492.4076 Ron Athey, Gifts of the Spirit: Automatic Writing, Whitworth Hall, Manchester, 27 June 2011. Photograph © Roshana Rubin-Mayhew. Ron Athey Gifts of the Spirit: Automatic Writing Automatic Writing Workshop July 23-27, 2013 For participants only, see enclosed call for applicants Ron Athey Gifts of the Spirit: Automatic Writing Saturday, July 27, 9pm Public performance Pleading in the Blood: The Art and Performances of Ron Athey Monday, July 29, 7pm Artist talk and book launch I had a dream in which I spewed ectoplasm: I opened my mouth and a manifesto poured out… --Ron Athey, Gifts of the Spirit, script 253 East Houston Street NY NY 10002 Ron Athey is presented in Association with the Grace Exhibition Space for Performance Art, Brooklyn www.Grace-Exhibition-Space.com Front cover image courtesy of Regis Hertrich, from Athey’sSolar Anusat The Hayward Gallery, London. Curated by Lee Adams for the Undercover Surrealism exhibition (2006). Pleading in the Blood: The Art and Performances of Ron Athey Monday, July 29, 7pm Artist talk and book launch, admission free, books for sale $35 Pleading in the Blood: The Art and Performances of Ron Athey is the first publication surveying the artist's career and impact from its origins to the present. Published this summer by Intellect Live and edited by Dominic Johnson,Pleading in the Bloodincludes three newly commissioned essays on different aspects of Athey’s work by Adrian Heathfield, Amelia Jones, and Dominic Johnson. These scholarly essays are complemented by shorter texts by Homi K. -

Time-Based History: Perspectives on Documenting Performance

REVIEW ESSAY Time-Based History: Perspectives on Documenting Performance Nik Wakefield In this review of literature on performance documentation, I aim to highlight strengths and weaknesses of existing scholarship in order to suggest ways in which the field might develop. Although I will be most forthright about my own stakes in this development at the conclusion of this review, I should say that my perspective is oriented toward the fields of performance philosophy and practice as research, while also invested in fashioning a temporal aesthetics, or what I call the time-specificity of performance. This text is positioned a step before a more fulsome elaboration of time-specificity but nevertheless addresses the need for such a concept through its very process of selection. For example, the kinds of literature to be found here are mostly all located after performance. Few take account of the production of documents before and during performance, such as the scores that are a part of much contemporary dance practice or the elements of performance that are being taken up by many in the field of poetic practice. Part of what time-specificity acknowledges is the multiple temporalities of performance: the before, during, and after, and how they persist through time. This review begins with the notion of ephemerality as ontological disappearance, as posited by Peggy Phelan. I also take up the wide array of responses to Phelan from performance theory and practice, while also adding in some perspectives from art history and criticism, philosophy, and political theory. Some of these writings were published before Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (1993) but were not included in that study nor taken up as responses to it. -

Live Art Development Agency Publications Catalogue

Live Art Development Agency Publications Catalogue Ron Athey is an iconic figure in the development of contemporary art and Contributors performance. In his frequently bloody portrayals of life, death, crisis, and Ron Athey fortitude in the time of AIDS, Athey calls into question the limits of artistic Homi K. Bhabha practice. These limits enable Athey to explore key themes including: gender, sexuality, SM and radical sex, queer activism, post-punk and Alex Binnie industrial culture, tattooing and body modification, ritual, and religion. Jennifer Doyle Pleading in the Blood: The Art and Performances of Ron Athey presents Tim Etchells the first critical overview of this major artist’s work. It demonstrates how Guillermo Gómez-Peña Athey foresaw and precipitated the central place afforded the body and Matthew Goulish T PLEADING IN THE BLOOD identity politics in art and critical theory in the 1990s and beyond. HE Catherine (Saalfield) Gund PLEADING IN A Adrian Heathfield RT T H E B L O O D Antony Hegarty AND Dominic Johnson T HE A RT AND Amelia Jones P ERFORMANCES Bruce LaBruce P ERFORMANCES Lydia Lunch OF R ON ATHEY Catherine Opie Juliana Snapper e d i t e d b y Julie Tolentino dominic johnson Robert Wilson OF R ON A THEY At long last, Dominic Johnson’s book begins the dauntingly exhilarating task of assessing the richly provocative art of Ron Athey. Incorporating Athey’s own prose version of his extraordinary childhood, astute critical essays, and moving appreciations from other artists, Pleading in the Blood advances Performance Studies and Art History by forging a mode of commentary expansive enough to address an artist who consistently works to expand the intricate drama of human embodiment. -

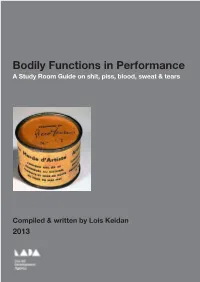

Bodily Functions in Performance a Study Room Guide on Shit, Piss, Blood, Sweat & Tears

Bodily Functions in Performance A Study Room Guide on shit, piss, blood, sweat & tears Compiled & written by Lois Keidan 2013 LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specific themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Cover Image credit: Piero Manzoni, Merda d’artista, 1961 Bodily Functions In Performance A Study Room Guide on Shit, Piss, Blood, Sweat And Tears. 1 2 The following are notes for Lois Keidan’s presentation for Blackmarket No 11 2008, on the theme of bodily functions in performance, with added images and recommendations for further research and study. Blackmarket for Useful Knowledge and Non-Knowledge No 11 On WASTE: The Disappearance and Comeback of Things Saturday 29 November, 2008, Liverpool A Blackmarket is an interdisciplinary research on learning and un-learning where narrative formats of knowledge transfer are tried out and presented. The installation imitates familiar places of knowledge exchange, like the archive or library reading room, and combines them with communication situations such as markets, stock exchanges, counselling or social service interviews.