Meromedga, 5, Part VI, Volume-IV, Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG2305 GPOBA for OBA Sanitation Microfinance Program in Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) May 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. Introduction 5 1. Background and context 5 2. The GPOBA Sanitation Microfinance Programme 6 C. Social Impact Assessment 7 1. Ethnic Minorities/Indigenous Peoples in Bangladesh 7 2. Purpose of the Small Ethnic Communities and Vulnerable Peoples Development Framework (SECVPDF) 11 D. Information Disclosure, Consultation and Participation 11 E. Beneficial measures/unintended consequences 11 F. Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) 12 G. Monitoring and reporting 12 H. Institutional arrangement 12 A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With the Government of Bangladesh driving its National Sanitation Campaign from 2003-2012, Bangladesh has made significant progress in reducing open defecation, from 34 percent in 1990 to just once percent of the national population in 20151. Despite these achievements, much remains to be done if Bangladesh is to achieve universal improved2 sanitation coverage by 2030, in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Bangladesh’s current rate of improved sanitation is 61 percent, growing at only 1.1 percent annually. To achieve the SDGs, Bangladesh will need to provide almost 50 million rural people with access to improved sanitation, and ensure services are extended to Bangladesh’s rural poor. Many households in rural Bangladesh do not have sufficient cash on hand to upgrade sanitation systems, but can afford the cost if they are able to spread the cost over time. -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

An Ethnographic Study on Traditional Marietal Rituals & Practices Among Bhumij Tribe of Bankura District, West Bengal, India

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 9, September 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A An Ethnographic Study on Traditional Marietal Rituals & Practices among Bhumij Tribe of Bankura District, West Bengal, India Priyanka Kanrar* ABSTRACT: Marriage is the physical, mental and spiritual union of two souls. It brings significant stability and substance to human relationships. Every ethnic community follows their own traditional marietal rituals and practices. Any ethnographic study of a ethnic group is incomplete without the knowledge of marietal practices of that community. So, the main objectives of the present study is to find out the types of marriages which was held among this Bhumij tribes. Also o find out the rules of marriage of this village. Know about the detail description about Bhumij traditional marriage rituals and practices. And also to find out the step by step marital rituals practices of this tribal population- from Pre-marital rituals to the Post-marital rituals practices. Mainly case study method is used for primary data collection. Case study method is very much useful for collect a very detail data from a particular individual. This method is very much applicable for this present study. Another method is observation method. It is simply used when primary data were collected. -

Inner Frontiers; Santal Responses to Acculturation

Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Report Chr. Michelsen Institute Department of Social Science and Development ISSN 0803-0030 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Bergen, December 1991 · CHR. MICHELSEN INSTITUTE Department of Social Science and Development ReporF1991: 6 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marine Carrin-Bouez Bergen, December 1991. 82 p. Summary: The Santals who constitute one of the largest communities in India belong to the Austro- Asiatie linguistic group. They have managed to keep their language and their traditional system of values as well. Nevertheless, their attempt to forge a new identity has been expressed by developing new attitudes towards medicine, politics and religion. In the four aricles collected in this essay, deal with the relationship of the Santals to some other trbal communities and the surrounding Hindu society. Sammendrag: Santalene som utgjør en av de tallmessig største stammefolkene i India, tilhører den austro- asiatiske språkgrppen. De har klar å beholde sitt språk og likeså mye av sine tradisjonelle verdisystemer. Ikke desto mindre, har de også forsøkt å utvikle en ny identitet. Dette blir uttrkt gjennom nye ideer og holdninger til medisin, politikk og religion. I de fire artiklene i dette essayet, blir ulike aspekter ved santalene sitt forhold til andre stammesamfunn og det omliggende hindu samfunnet behandlet. Indexing terms: Stikkord: Medicine Medisin Santal Santal Politics Politik Religion -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abdul in Bangladesh Ansari in Bangladesh Population: 30,000 Population: 14,000 World Popl: 66,200 World Popl: 14,792,500 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 6 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Ansari Main Language: Bengali Main Language: Bengali Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Isudas Source: Biswarup Ganguly "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arleng in Bangladesh Asur in Bangladesh Population: 900 Population: 1,200 World Popl: 500,900 World Popl: 33,200 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other Main Language: Karbi Main Language: Sylheti Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 9.26% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Mangal Rongphar "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Baiga in Bangladesh Bairagi (Hindu traditions) in Bangladesh Population: -

Swap an Das' Gupta Local Politics

SWAP AN DAS' GUPTA LOCAL POLITICS IN BENGAL; MIDNAPUR DISTRICT 1907-1934 Theses submitted in fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy degree, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1980, ProQuest Number: 11015890 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015890 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis studies the development and social character of Indian nationalism in the Midnapur district of Bengal* It begins by showing the Government of Bengal in 1907 in a deepening political crisis. The structural imbalances caused by the policy of active intervention in the localities could not be offset by the ’paternalistic* and personalised district administration. In Midnapur, the situation was compounded by the inability of government to secure its traditional political base based on zamindars. Real power in the countryside lay in the hands of petty landlords and intermediaries who consolidated their hold in the economic environment of growing commercialisation in agriculture. This was reinforced by a caste movement of the Mahishyas which injected the district with its own version of 'peasant-pride'. -

TRIBAL COMMUNITIES of ODISHA Introduction the Eastern Ghats Are

TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF ODISHA Introduction The Eastern Ghats are discontinuous range of mountain set along Eastern coast. They are located between 11030' and 220N latitude and 76050' and 86030' E longitude in a North-East to South-West strike. It covers total area of around 75,000 sq. km. Eastern Ghats are often referred to as “Estuaries of India”, because of high rainfall and fertile land that results into better crops1. Eastern Ghat area is falling under tropical monsoon climate receiving rainfall from both southwest monsoon and northeast retreating monsoon. The northern portion of the Ghats receives rainfall from 1000 mm to 1600 mm annually indicating sub-humid climate. The Southern part of Ghats receives 600 mm to 1000 mm rainfall exhibiting semi arid climate2. The Eastern Ghats is distributed mainly in four States, namely, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The part of Eastern Ghats found in the Odisha covers 18 districts, Andhra Pradesh 15 districts and Tamil Nadu in 9 districts while Karnataka Eastern Ghats falls in part of Chamrajnagar and Kolar3. Most of the tribal population in the State is concentrated in the Eastern Ghats of high attitude zone. The traditional occupations of the tribes vary from area to area depending on topography, availability of forests, land, water etc. for e.g. Chenchus tribes of interior forests of Nallamalai Hills gather minor forest produce and sell it in market for livelihood while Konda Reddy, Khond, Porja and Savara living on hill slopes pursue slash and burn technique for cultivation on hill slopes. The Malis of Visakhapatnam (Araku) Agency area are expert vegetable growers. -

Life in a Bhumij Village During Lockdown: an Explorative Study

SJIF Impact Factor: 7.001| ISI I.F.Value:1.241| Journal DOI: 10.36713/epra2016 ISSN: 2455-7838(Online) EPRA International Journal of Research and Development (IJRD) Volume: 5 | Issue: 8 | August 2020 - Peer Reviewed Journal LIFE IN A BHUMIJ VILLAGE DURING LOCKDOWN: AN EXPLORATIVE STUDY Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed1 1Assistant Professor, Department of Education, Haldia Govt. College, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India Biswajit Goswami2 2Ph.D. Research Scholar, Swami Vivekananda Centre for Multidisciplinary Research in Educational Studies, University of Calcutta recognized Research Centre under Ramakrishna Mission Sikshanamandira, Belur Math, Howrah, West Bengal, India Swami Tattwasarananda3 3 Professor, Ramakrishna Mission Sikshanamandira, Belur Math, Howrah, West Bengal, India Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.36713/epra4902 ABSTRACT Since midnight of March 25, 2020, India's 1.3 billion people had gone under total lockdown to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and this prolonged countrywide lockdown has a serious impact on the life of the Indian tribes like their income, occupation, social life, personal life etc., as they are the most vulnerable and poor marginalized people of India, having neglected through the ages in every aspect of their life and livelihood. Bhumij tribe is one of them. They mainly reside in the Indian state of Odisha, Jharkhand, and West Bengal. Lutia is a typical Bhumij concentrated village in the area of Simlabandh under Hirbandh community development block of Khatra sub-division in the district of Bankura of the Indian state of West Bengal. By maintaining proper social distance and wearing face mask we have taken in-depth interview of 25 villagers of different age group and gender belong to Bhumij tribal community in this village on the various aspects of their day to day life, their education, their health awareness especially about the awareness regarding COVID- 19, their culture, religious and supernatural beliefs, etc. -

Sylhet, Bangladesh UPG 2018

Country State People Group Language Religion Bangladesh Sylhet Abdul Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Ansari Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Arleng Karbi Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, WesternOther / Small Bangladesh Sylhet Baiga Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bania Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bauri Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Behara Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Beldar (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bhumij Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bihari (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Birjia Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bishnupriya Manipuri BishnupuriyaHinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Bodo Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Gaur Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Joshi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Kanaujia Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Radhi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Sakaldwipi Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Saraswat Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin unspecified Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Utkal Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Vaidik Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Brahmin Varendra Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Burmese Burmese Buddhism Bangladesh Sylhet Chamar (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Chero Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Chik Baraik Sylheti Hinduism Bangladesh Sylhet Dai (Muslim traditions) Bengali Islam Bangladesh Sylhet Dalu Bengali Islam Bangladesh -

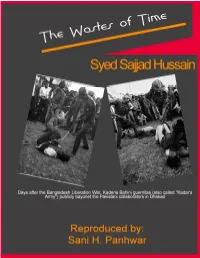

The Wastes of Time by Syed Sajjad Hussain

THE WASTES OF TIME REFLECTIONS ON THE DECLINE AND FALL OF EAST PAKISTAN Syed Sajjad Husain 1995 Reproduced By: Sani H. Panhwar 2013 Syed Sajjad Syed Sajjad Husain was born on 14th January 1920, and educated at Dhaka and Nottingham Universities. He began his teaching career in 1944 at the Islamia College, Calcutta and joined the University of Dhaka in 1948 rising to Professor in 1962. He was appointed Vice-Chancellor of Rajshahi University July in 1969 and moved to Dhaka University in July 1971 at the height of the political crisis. He spent two years in jail from 1971 to 1973 after the fall of East Pakistan. From 1975 to 1985 Dr Husain taught at Mecca Ummul-Qura University as a Professor of English, having spent three months in 1975 as a Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. Since his retirement in 1985, he had been living quietly at home and had in the course of the last ten years published five books including the present Memoirs. He breathed his last on 12th January, 1995. A more detailed account of the author’s life and career will be found inside the book. The publication of Dr Syed Sajjad Husain’s memoirs, entitled, THE WASTES OF TIME began in the first week of December 1994 under his guidance and supervision. As his life was cut short by Almighty Allah, he could read and correct the proof of only the first five Chapters with subheadings and the remaining fifteen Chapters without title together with the Appendices have been published exactly as he had sent them to the publisher. -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified.