Article • Ocular Examination of the Deaf Patient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Nd:YAG Laser Capsulotomy in Posterior Capsular Opacification

Original Research Article Effects of Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy in posterior capsular opacification Praveen Kumar G S1, Lavanya P2*, Raviprakash D3 1Assistant Professor, 2Associate Professor, 3Professor & HOD, Department of Ophthalmology, Shridevi institute of Medical Sciences and Research Hospital, Sira Road, NH-4 Bypass Road, Tumkur- 572106, INDIA. Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Posterior capsular opacification (PCO) is the most common long-term complication of cataract surgery in both phacoemulsification and extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE). The overall incidence of PCO and the incidence of neodymium-doped yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Nd:YAG) laser posterior capsulotomy has decreased from 50% in the 1980s and early 1990s to less than 10% today. Reported complications of Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy include elevated intraocular pressure, iritis, corneal damage, intraocular lens (IOL) damage, cystoids macular edema, disruption of the anterior hyaloid surface, increased risk of retinal detachment, and IOL movement or dislocation. In some patients, a refraction change is noticed after Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy, but proving this remains difficult. Materials and Methods: Nd; YAG LASER capsulotomy was performed in 200 eyes of 200 patients, some with pseudophakia and some with aphakia at Kurnool medical college, Kurnool. They were followed up between October 2008 and September 2010. Results: Elevation of IOP has been well documented after anterior segment laser procedures. The IOP rise after YAG laser posterior capsulotomy is of short duration starting about 1 hr after laser procedure and lasting for 24 hrs. In this study, in 1case IOP came down to normal level after 3 days and in another case after 7 days. -

Ophthalmology Abbreviations Alphabetical

COMMON OPHTHALMOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS Listed as one of America’s Illinois Eye and Ear Infi rmary Best Hospitals for Ophthalmology UIC Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences by U.S.News & World Report Commonly Used Ophthalmology Abbreviations Alphabetical A POCKET GUIDE FOR RESIDENTS Compiled by: Bryan Kim, MD COMMON OPHTHALMOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS A/C or AC anterior chamber Anterior chamber Dilators (red top); A1% atropine 1% education The Department of Ophthalmology accepts six residents Drops/Meds to its program each year, making it one of nation’s largest programs. We are anterior cortical changes/ ACC Lens: Diagnoses/findings also one of the most competitive with well over 600 applicants annually, of cataract whom 84 are granted interviews. Our selection standards are among the Glaucoma: Diagnoses/ highest. Our incoming residents graduated from prestigious medical schools ACG angle closure glaucoma including Brown, Northwestern, MIT, Cornell, University of Michigan, and findings University of Southern California. GPA’s are typically 4.0 and board scores anterior chamber intraocular ACIOL Lens are rarely lower than the 95th percentile. Most applicants have research lens experience. In recent years our residents have gone on to prestigious fellowships at UC Davis, University of Chicago, Northwestern, University amount of plus reading of Iowa, Oregon Health Sciences University, Bascom Palmer, Duke, UCSF, Add power (for bifocal/progres- Refraction Emory, Wilmer Eye Institute, and UCLA. Our tradition of excellence in sives) ophthalmologic education is reflected in the leadership positions held by anterior ischemic optic Nerve/Neuro: Diagno- AION our alumni, who serve as chairs of ophthalmology departments, the dean neuropathy ses/findings of a leading medical school, and the director of the National Eye Institute. -

Study of Visual Outcome After Neodymium YAG Laser Therapy in Posterior Capsular Opacity

perim Ex en l & ta a l O ic p in l h t C h f a o l m l Journal of Clinical and Experimental a o n l r o g u y o J ISSN: 2155-9570 Ophthalmology Research article Study of Visual Outcome after Neodymium YAG Laser Therapy in Posterior Capsular Opacity Pawan N. Jarwal* Department of Ophthalmology, Jaipuriya Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India ABSTRACT Purpose: Posterior capsular opacification is the most common long term complication of modern IOL surgery. Neodymium YAG laser remains the cornerstone of its treatment .In this study, an attempt was made to study the visual outcome following Neodymium YAG laser capsulotomy Methods: This was a prospective study of 50 patients conducted in Hospital , attached to R.U.H.S.-CMS Medical College ,Jaipur. All patients aged 50 years and above, attending the regular OPD who presented with visually significant posterior capsular opacification were treated with Neodymium YAG laser capsulotomy. After capsulotomy, follow up was done 1 – 4 hour after Capsulotomy, day one, end of first week, end of first month and at the end of minimum 3 months. During follow-up the visual acuity Intra Ocular Pressure (IOP) and other relevant tests were conducted and appropriate intervention were made during the follow-up period. Results: In my study duration of onsetofsymptoms of Posteriorcapsularopacity (PCO) is more between 2-3 years period after surgery. Pearls type of is Posteriorcapsular opacity more when compared to fibrous type. Most of the patients treated for Posterior capsular opacity with Neodymium: YAG laser capsulotomy showed an improvement in visual acuity .There was no incidence of major complications in patients treated with procedure. -

Visual Impairment Care Needs of the Public Through Clinical Care, Research, and Education, All of Which Enhance the Quality of Life

OPTOMETRY: OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION PRACTICE GUIDELINE Doctors of optometry (ODs) are the primary health care professionals for the eye. Optometrists examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases, injuries, and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as identify related systemic conditions affecting the eye. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. Approximately 37,000 full-time equivalent doctors of optometry practice in more than 7,0000 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care provider in more than 4,300 communities. Care of the Patient with The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye Visual Impairment care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. (Low Vision Rehabilitation) OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENT (LOW VISION REHABILITATION) Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Low Vision Kathleen Fraser Freeman, O.D., Principal Author Roy Gordon Cole, O.D. Eleanor E. Faye, M.D. Paul B. Freeman, O.D. Gregory L. Goodrich, Ph.D. Joan A. Stelmack, O.D. Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. Heath, O.D., Chair John F. Amos, O.D., M.S. Stephen C. Miller, O.D. -

IOC Mednick: Challenging Surgical Cases

Top 5 Pearls to Consider When Implanting Advanced Technology IOLs in Patients With Unusual Circumstances Zale D. Mednick, BA Guillermo Rocha, MD, FRCSC ’ Pearl #1: The Use of a Toric Multifocal Intraocular Lens (IOL) in the Management of Hyperopic Astigmatism Background The mainstay of treatment for those with hyperopic astigmatism who wish to bypass the need for glasses or contacts has traditionally been laser treatment. Both hyperopic laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and photorefractive keratotomy (PRK) have been used to correct hyperopic astigmatism. Although LASIK can provide promising results for a portion of patients with hyperopic eyes, it becomes less effective when dealing with more exaggerated degrees of hyperopia. Refractive results are much more successful for low diopter (D) hyperopia, with a drop in efficacy starting at + 4.00 to + 5.00 D.1 Esquenazi and Mendoza2 reported that when LASIK is performed on eyes with >5.00 D of hyperopia, both the safety profile of the procedure and the refractive outcomes dramatically decline, coinciding with decreased corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA). Choi and Wilson3 echoed this notion, citing a 2-line drop in CDVA when LASIK was used to treat hyperopia of 5.00 to 8.75 D. This is in stark contrast to the results achieved by LASIK to improve myopia, where corrections are feasible for a far greater range of refractions. Part of the reason that hyperopia is less amenable to correction of higher diopter errors may owe to the fact that larger ablation zones are needed to achieve better refractive results.4 The optimal size of the ablation zone for hyperopic LASIK is >5.5 mm,1 and as such, more corneal alteration is required. -

Design and Methods in the Eye and Vision Consortium of UK Biobank

Open access Cohort profile BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025077 on 21 February 2019. Downloaded from Cohort profile: design and methods in the eye and vision consortium of UK Biobank Sharon Yu Lin Chua,1 Dhanes Thomas,1 Naomi Allen,2 Andrew Lotery,3 Parul Desai,1 Praveen Patel,1 Zaynah Muthy,1 Cathie Sudlow,4 Tunde Peto,5 Peng Tee Khaw,1 Paul J Foster,1 UK Biobank Eye & Vision Consortium To cite: Chua SYL, Thomas D, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Allen N, et al. Cohort profile: Purpose To describe the rationale, methods and research design and methods in the potential of eye and vision measures available in UK ► UK Biobank is the largest prospective cohort with eye and vision consortium Biobank. of UK Biobank. BMJ Open extensive measures on ophthalmic diseases and Participants UK Biobank is a large, multisite, prospective 2019;9:e025077. doi:10.1136/ conditions. cohort study. Extensive lifestyle and health questionnaires, bmjopen-2018-025077 ► Repeated physical measures every few years and a range of physical measures and collection of biological linkage to National Health Service records will pro- ► Prepublication history for specimens are collected. The scope of UK Biobank was vide valuable information on health outcomes. this paper is available online. extended midway through data collection to include ► A large number of incident cases of eye diseases in To view these files, please visit assessments of other measures of health, including eyes the journal online (http:// dx. doi. 5 years will allow the detection and quantification of and vision. -

Peripheral Refraction Vs. Optical Coherence Tomography

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Comparison of Methods for Estimating Retinal Shape: Peripheral Refraction vs. Optical Coherence Tomography Katharina Breher 1,* , Alejandro Calabuig 1 , Laura Kühlewein 1,2 , Focke Ziemssen 2 , Arne Ohlendorf 3 and Siegfried Wahl 1,3 1 Institute for Ophthalmic Research, University of Tübingen, 72076 Tübingen, Germany; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (L.K.); [email protected] (S.W.) 2 Center for Ophthalmology, University of Tübingen, 72076 Tübingen, Germany; [email protected] 3 Carl Zeiss Vision International GmbH, 73430 Aalen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Retinal shape presents a clinical parameter of interest for myopia, and has commonly been inferred indirectly from peripheral refraction (PRX) profiles. Distortion-corrected optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans offer a new and direct possibility for retinal shape estimation. The current study compared retinal curvatures derived from OCT scans vs. PRX measurements in three refractive profiles (0◦ and 90◦ meridians, plus spherical equivalent) for 25 participants via Bland–Altman analysis. The radial differences between both procedures were correlated to axial length using Pearson correla- tion. In general, PRX- and OCT-based retinal radii showed low correlation (all intraclass correlation coefficients < 0.21). PRX found flatter retinal curvatures compared to OCT, with the highest absolute agreement found with the 90◦ meridian (mean difference +0.08 mm) and lowest in the 0◦ meridian (mean difference +0.89 mm). Moreover, a negative relation between axial length and the agreement of both methods was detected especially in the 90◦ meridian (R = −0.38, p = 0.06). -

Efficacy of Plasma Knife Assisted Posterior Capsulotomy Versus

Prakash S, Giridhar, Harshila Jain. Efficacy of plasma knife assisted posterior capsulotomy versus manual primary posterior capsulorhexis in preventing visual axis opacification in pediatric cataract surgery: A randomized controlled trial. IAIM, 2017; 4(9): 171-177. Original Research Article Efficacy of plasma knife assisted posterior capsulotomy versus manual primary posterior capsulorhexis in preventing visual axis opacification in pediatric cataract surgery: A randomized controlled trial Prakash S1*, Giridhar2, Harshila Jain3 1Assistant Professor, 2Professor and Head, 3Associate Professor Department of Ophthalmology, Dhanalakshmi Srinivasan Medical College and Hospital, Siruvachur, Perambalur, India *Corresponding author email: [email protected] International Archives of Integrated Medicine, Vol. 4, Issue 9, September, 2017. Copy right © 2017, IAIM, All Rights Reserved. Available online at http://iaimjournal.com/ ISSN: 2394-0026 (P) ISSN: 2394-0034 (O) Received on: 04-09-2017 Accepted on: 13-09-2017 Source of support: Nil Conflict of interest: None declared. How to cite this article: Prakash S, Giridhar, Harshila Jain. Efficacy of plasma knife assisted posterior capsulotomy versus manual primary posterior capsulorhexis in preventing visual axis opacification in pediatric cataract surgery: A randomized controlled trial. IAIM, 2017; 4(9): 171-177. Abstract Background: Posterior capsule opacification (PCO) is the commonest complication of extracapsular catraract surgery in pediatric patients with an incidence as high as 95%. But there is inadequate evidence on appropriate intervention to prevent PCO. Aim: To compare the efficacy of plasma knife assisted posterior capsulotomy versus manual primary posterior capsulorhexis in Pediatric Cataract surgery. Materials and methods: The current study was a randomized open labeled controlled study, conducted in the department of ophthalmology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi between July 2015 to June 2016. -

Detection of Specific Difficulties of Retinoscopy Including the Types

Detection Of Specific Difficulties Of Retinoscopy Including The Types Of Refractive Errors Using Retinoscope Among The Students Of The Islamic University Of Gaza- Palestine Yassin Al-nouno and Sami Shublaq Optometry department Faculty of science Introduction The technique of retinoscopy is used to objectively determine the refractive status of the eye relative to the point of fixation. Retinoscopy is usually the first technique performed during the ocular examination that determines the patient's refractive status, and it is immediately followed by the subjective refraction. Some refractions are easy; some are extremely difficult. So the special difficulties need the supervision of competent optometrist. Objectives : 1. The prevalence of special difficulties in retinoscopy among a group of (IUG) students. 2. To determine differences in refractive errors according to types and sex. Material and Methods: Study subjects comprised 1116 students. Males represented 33% (n=369) while females represented 67% (n=747) study was conducted between 1 October 2009 to 31 March 2011. (Table 1) We checked sex, age, address, vision without glasses and the visual acuity with glasses. The results showed that 937 cases (84%) were within normal "emmetropic cases", on the other hands, 179 cases (16%) were found to be abnormal "ametropic cases", they needed correction. The age of all cases was 18-24 years Table 1 : Distribution of the study group according to sex No Classification Total Percentage 1 Males 369 33% 2 Females 747 67% Grand total 1116 100% Table 2 : Refractive errors among cases No Types of refractive errors Total Percentage 1 Myopia 55 30.73% 2 Hypermetropia 7 3.91% 3 Astigmatism 9 5.03% 4 Myopic astigmatism 104 58.10% 5 Hypermetropic astigmatism 4 2.23% Grand total 179 100% A total of 23 cases “12.84%” showed with special difficulties in retinoscopy out of 179 cases who suffered from refractive errors. -

Diabetic Retinopathy by the Numbers a Guide to Following and Educating Patients LACRIMAL OCCLUSION ■ Who Face This Threatening Diagnosis, P

REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY Earn 2 CE Credits: Can You Identify These Vitreous Anomalies?, p. 94 ■ VOL. 153 NO. 6 June 15, 2016 www.reviewofoptometry.com ■ JUNE 15, 2016 ■ ANNUAL 7th Annual Retina Report RETINA REPORT Diabetic Retinopathy By the Numbers ■ A guide to following and educating patients LACRIMAL OCCLUSION who face this threatening diagnosis, p. 36 • Food for Thought: Diet, Genetics and AMD, p. 48 • The Dilation Dilemma p. 54 • Managing Patients with ■ VITREOUS ANOMALIES Hypertensive Crisis, p. 58 ■ VIRAL CONJUNCTIVITIS 125 YEARS Plug the Drain with Lacrimal Occlusion, p. 70 | Claim Victory Over Viral Conjunctivitis, p. 78 001_ro0616_fc.indd 1 6/9/16 9:57 AM We call it our fundamental business truth: 1 20/200 Your success is essential to Our success. When your practice grows and flourishes, so does ours. At Johnson & Johnson Vision Care, we have operated according to this simple, but profound, principle for over 30 years. And it is the inspiration and 2 20/100 energy behind every year of our 3 decades of Global leadership in the contact lens marketplace. But history tells only a small part of the story. It is what we will do together in partnership over 3 20/70 the next 3 decades that will truly change the very meaning of vision care. Our commitment to innovation is unwavering. 4 20/50 But at the center of all of the R & D eff orts—be they technological, educational, or commercial in nature— is our commitment to advancing the eye care profession. 5 20/40 We thank you for your partnership and look forward to the continued journey together. -

Near Dynamic Retinoscopy

1/13/2015 Retinoscopy Near Dynamic Retinoscopy • Why do we do retinoscopy? It’s Not Your Mother’s Retinoscopy • If simply to arrive at a “refraction,” we are limiting the information we are getting Glen T. Steele, O.D. FCOVD FAAO • Retinoscopy for refraction is like Twitter – limited Professor of Pediatric Optometry understanding Southern College of Optometry • If you are trying to determine how someone is attempting to obtain information and the amount Memphis, TN of energy required and monitor these changes through time, longer observations are necessary Retinoscopy Retinoscopy • What skills do we expect a child to show when we • How frequently do you have to remind them to look evaluate? • What if their eyes point at the target but you see marked • Look changes in the reflex – balance, brightness, motion and color • Align • This is a direct measure of self-regulation – important for • Follow later classroom activity • Focus – ability • Also a developmental test – Are they fully ready to look and • Focus – sustain sustain looking? Retinoscopy My Retinoscopy Tenets • How do we assess whether they can do that or not? • Retinoscopy should be our mental video of what • Qualitative AND quantitative measures goes into all those things that make up what we • Subjective compared to objective responses call “refractive state” • As a part of other testing • Observing the process of effective looking requires patience on the part of the patient – and the • All of the above optometrist • We often rush to the conclusion – with considerable impatience -

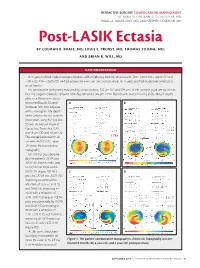

Post-LASIK Ectasia by COLMAN R

REFRACTIVE SURGERY COMPLICATIONS MANAGEMENT SECTION EDITORS: KARL G. STONECIPHER, MD; PARAG A. MAJMUDAR, MD; AND STEPHEN COLEMAN, MD Post-LASIK Ectasia BY COLMAN R. KRAFF, MD; LOUIS E. PROBST, MD; THOMAS TOOMA, MD; AND BRIAN R. WILL, MD CASE PRESENTATION A 34-year-old black male underwent bilateral LASIK in February 2000 for refractions of -7.00 +3.00 X 100 = 20/20 OD and -7.00 +3.25 X 85 = 20/20 OS. He had successfully worn soft toric contact lenses for 15 years and had no pertinent medical or ocular history. His preoperative pachymetry measured by ultrasound was 535 µm OD and 529 µm OS. His scotopic pupil size was 6 mm OU. The surgeon created a 137-µm LASIK flap OD and a 146-µm LASIK flap OS with an 8.5-mm ring and a 180-µm depth plate on a Hansatome micro- keratome (Bausch & Lomb, AB Rochester, NY). Not adjusted with a nomogram, the depth of the ablation for this patient’s prescription using the Visx Star S2 laser (Advanced Medical Optics, Inc., Santa Ana, CA) was 59 µm OD and 58 µm OS. The average keratometric val- ues were 46.00 D OU. Figure 1A shows the preoperative topography. On the first postoperative day, the patient’s UCVA was 20/20 OU. Nine months later, his UCVA had improved to 20/15 OU (Figure 1B). At 2 CD years, his UCVA was 20/25 OD, improving to 20/20 with a refraction of -0.75 +1.75 X 10, and 20/40 OS, improving to 20/20 with a refraction of -2.00 +2.00 X 20 (Figure 1C).