Breast-Feeding and Child-Spacing: Importance of Information Collection for Public Health Policy R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex-Selective Abortions, Fertility, and Birth Spacing*

Sex-Selective Abortions, Fertility, and Birth Spacing* Claus C Portner¨ Department of Economics Albers School of Business and Economics Seattle University, P.O. Box 222000 Seattle, WA 98122 [email protected] www.clausportner.com & Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology University of Washington November 2016 *I am grateful to Andrew Foster and Darryl Holman for discussions about the method. I owe thanks to Shelly Lundberg, Daniel Rees, David Ribar, Hendrik Wolff, seminar participants at University of Copenhagen, University of Michigan, University of Washington, University of Arhus,˚ the Fourth Annual Conference on Population, Repro- ductive Health, and Economic Development, and the Economic Demography Workshop for helpful suggestions and comments. I would also like to thank Nalina Varanasi for research assistance. Support from the University of Wash- ington Royalty Research Fund and the Development Research Group of the World Bank is gratefully acknowledged. The views and findings expressed here are those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or any of its member countries. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, 5R24HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology at the University of Washington. Prior versions of this paper were presented under the title “The Determinants of sex-selective Abortions.” Abstract This paper addresses two main questions: what is the relationship between fertility and sex se- lection and how does birth spacing interact with the use of sex-selective abortions? I introduce a statistical method that incorporates how sex-selective abortions affect both the likelihood of a son and spacing between births. -

Pre and Interconception Health, Intentionality and Birth Spacing: Emerging Issues

PRE AND INTERCONCEPTION HEALTH, INTENTIONALITY AND BIRTH SPACING: EMERGING ISSUES Monday, May 21 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM #prematuritycollab Pre- and Interconception Health, Intentionality, and Birth Spacing: Emerging Approaches Prematurity Prevention Summit Building a Birth Equity Movement Welcome • Co-chairing the Prematurity Collaborative Clinical and Public Health Practice Workgroup ‣ With Vanessa Lee, MPH (HRSA) • Great group of people; very dedicated • Focus on 3 main topics: ‣ 17-P ‣ LDASA ‣ Intentionality and birth spacing Background • Approximately half of pregnancies in US are unintended ‣ Better in teens, but still unacceptably high • Intentionality is important ‣ Unintended pregnancy associated with adverse maternal and child outcomes ‣ Negative impact on physical and mental health ‣ Disproportionate impact › Higher rates in lower SES and lower levels of achieved education ‣ Expensive… › 2010 estimate: $21 billion in public expenditure for unintended pregnancy Background – Birth Spacing • Based on data suggesting short interpregnancy intervals associated with worse outcomes ‣ Including prematurity ‣ Others: fetal growth restriction, NICU admission, perinatal death • Intervals “debated”…. ‣ < 24 months, especially < 18 months • “Recommendations” to avoid short intervals ‣ Healthy People 2020 objective: 10% reduction in pregnancies within 18 months ‣ WHO: minimum birth-to-pregnancy spacing of 2 years ‣ ACOG: short intervals mentioned as a risk factor for preterm delivery and adverse neonatal outcomes • Widespread emphasis ‣ Made sense -

Glossary of Common MCH Terms and Acronyms

Glossary of Common MCH Terms and Acronyms General Terms and Definitions Term/Acronym Definition Accountable Care Organizations that coordinate and provide the full range of health care services for Organization individuals. The ACA provides incentives for providers who join together to form such ACO organizations and who agree to be accountable for the quality, cost, and overall care of their patients. Adolescence Stage of physical and psychological development that occurs between puberty and adulthood. The age range associated with adolescence includes the teen age years but sometimes includes ages younger than 13 or older than 19 years of age. Antepartum fetal Fetal death occurring before the initiation of labor. death Authorization An act of a legislative body that establishes government programs, defines the scope of programs, and sets a ceiling for how much can be spent on them. Birth defect A structural abnormality present at birth, irrespective of whether the defect is caused by a genetic factor or by prenatal events that are not genetic. Cost Sharing The amount an individual pays for health services above and beyond the cost of the insurance coverage premium. This includes co-pays, co-insurance, and deductibles. Crude birth rate Number of live births per 1000 population in a given year. Birth spacing The time interval from one child’s birth until the next child’s birth. It is generally recommended that at least a two-year interval between births is important for maternal and child health and survival. BMI Body mass index (BMI) is a measure of body weight that takes into account height. -

Packages of Interventions for Family Planning, Safe Abortion Care, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health WHO/FCH/10.06

Packages of Interventions for Family Planning, Safe Abortion care, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health WHO/FCH/10.06 Acknowledgement This document has been developed by the World Health Organization. It includes inputs from UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and different members of The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH). Bilateral partners also made valuable contributions. © World Health Organization 2010 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

Assessing the Impact of Birth Spacing on Child Health Trajectories

Global Development Policy Center HCI WORKING PAPER 001 • SEPT 2018 HUMAN CAPITAL INITIATIVE Assessing the Impact of Birth Spacing on Child Health Trajectories MAHESH KARRA ABSTRACT We investigate the effect of birth spacing between siblings on child health trajectories and invest- ments using longitudinal data from the Young Lives Study. We analyzed a birth cohort of over 7,000 children with data collected between 2002 and 2013 from four low- and middle-income countries. We found increased height among children who were more widely spaced relative to children who were narrowly spaced (within two years from an older sibling). However, we also found evidence of Mahesh Karra is an Assistant compensatory growth (converging height and HAZ scores) for closely spaced children as they aged. Professor of Global Development There was a positive association between birth spacing and prenatal investments, which suggests Policy at the Frederick S. that the emergence of height gaps could have been driven by parental behavior in addition to bio- Pardee School of Global Studies logical factors. However, we found little evidence that compensatory growth was driven by remedial at Boston University and health investments in closely spaced children after birth, suggesting catch-up growth as a biological Associate Director of the Human phenomenon. Available data suggests financial constraints and caregiver perceptions of child health Capital Initiative at the Global Development Policy Center. as possible explanations for lack of remedial investments. Keywords: birth spacing, health, nutrition, child investments, compensatory growth, height HCI@GDPCenter www.bu.edu/gdp Pardee School of Global Studies/Boston University 1 Introduction The importance of birth spacing for maternal and child health has been a long-standing source of interest to researchers and policymakers (World Health Organization, 2005). -

Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancies: a Family Planning Investment Strategy for Accelerating the Pace of Improvements in Child Survival

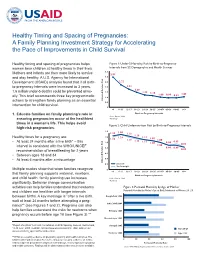

Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancies: A Family Planning Investment Strategy for Accelerating the Pace of Improvements in Child Survival Healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies helps Figure 1: Under-5 Mortality Risk by Birth-to-Pregnancy women bear children at healthy times in their lives. Intervals from 52 Demographic and Health Surveys 3.5 Mothers and infants are then more likely to survive 2.97 and stay healthy. A U.S. Agency for International 3.0 Development (USAID) analysis found that if all birth- 2.5 2.22 to-pregnancy intervals were increased to 3 years, 2.0 1.81 1.49 1.6 million under-5 deaths could be prevented annu- 1.5 1.22 1.14 1.00 0.96 0.92 1.05 ally. This brief recommends three key programmatic 1.0 actions to strengthen family planning as an essential Risk Adjusted Relative 0.5 intervention for child survival. 0 <6 6–11 12–17 18–23 24–29 30–35 36–47* 45–59 60–95 96+ 1. Educate families on family planning’s role in Birth-to-Pregnancy Intervals Source: Rutstein, 2008 ensuring pregnancies occur at the healthiest *Ref Group times in a woman’s life. This helps avoid Figure 2: Child Undernutrition Risk by Birth-to-Pregnancy Intervals high-risk pregnancies. 1.4 1.30 1.25 1.12 1.16 Healthy times for a pregnancy are: 1.2 1.29 1.11 1.22 1.07 1.19 1.13 1.00 • At least 24 months after a live birth* – this 1.0 1.11 0.90 0.95 1.06 0.82 interval is consistent with the WHO/UNICEF 1.00 0.8 0.90 0.89 recommendation of breastfeeding for 2 years 0.82 • Between ages 18 and 34 0.6 • At least 6 months after a miscarriage 0.4 Adjusted Relative Risk Adjusted Relative 0.2 Stunted Underweight Multiple studies show that when families recognize 0 <6 6–11 12–17 18–23 24–29 30–35 36–47* 45–59 60–95 96+ that family planning supports maternal, newborn, Birth-to-Pregnancy Intervals and child health, family planning use increases Source: Rutstein, 2008 *Ref Group signifi cantly. -

Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Sexual Risk Among Postpartum Women

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Sexual Risk among Postpartum Women Jordan L. Thomas 1 , Jessica B. Lewis 2 , Jeannette R. Ickovics 3,4 and Shayna D. Cunningham 5,* 1 Department of Psychology, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT 06510, USA; [email protected] 3 Yale-NUS College, Singapore 138527, Singapore; [email protected] 4 Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT 06510, USA 5 Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT 06032, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-860-679-7642 Abstract: Epidemiological evidence suggests that exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is associated with sexual risk, especially during adolescence, and with maternal and child health out- comes for women of reproductive age. However, no work has examined how ACE exposure relates to sexual risk for women during the postpartum period. In a convenience sample of 460 postpartum women, we used linear and logistic regression to investigate associations between ACE exposure (measured using the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale) and five sexual risk outcomes of im- portance to maternal health: contraceptive use, efficacy of contraceptive method elected, condom use, rapid repeat pregnancy, and incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). On average, women in the sample were 25.55 years of age (standard deviation = 5.56); most identified as Black Citation: Thomas, J.L.; Lewis, J.B.; Ickovics, J.R.; Cunningham, S.D. -

Sex Selective Abortions, Fertility and Birth Spacing∗

Sex Selective Abortions, Fertility and Birth Spacing∗ Claus C Portner¨ Department of Economics University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-3330 [email protected] http://faculty.washington.edu/cportner/ August 2010 ∗I am grateful to Andrew Foster and Darryl Holman for discussions about the method. I owe thanks to Shelly Lund- berg, Daniel Rees, David Ribar, seminar participants at University of Copenhagen, University of Michigan, University of Washington, University of Arhus,˚ the fourth Annual Research Conference on Population, Reproductive Health, and Economic Development, and the Economic Demography Workshop for helpful suggestions and comments. I would also like to thank Nalina Varanasi for research assistance. Support from the University of Washington Royalty Re- search Fund and the Development Research Group of the World Bank is gratefully acknowledged. The views and findings expressed here are those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or any of its member countries. Prior versions of this paper were presented under the title “The Determinants of Sex Selective Abortions.” Abstract Previous research on sex selective abortions has ignored the interactions between fertility, birth spacing and sex selection. This paper presents a novel approach that jointly estimates the determinants of sex selective abortions, fertility and birth spacing, using data from India’s National Family and Health Surveys. For well educated Indian women the predicted number of abortions during childbearing is six percent higher after sex selection became illegal than before while their predicted fertility is eleven percent lower and around replacement level. Women with less education have substantially higher fertility and do not appear to use sex selection. -

HTSP 101: Everything You Want to Know About Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy

HTSP 101: Everything You Want to Know About Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy (HTSP) is an intervention to help women and families delay or space their pregnancies to achieve the healthiest outcomes for women, newborns, infants, and children, within the context of free and informed choice, taking into account fertility intentions and desired family size. Background Over the past few years, the United States Agency Qualitative studies conducted by USAID in for International Development (USAID) has Pakistan, India, Bolivia, and Peru showed that sponsored a series of studies on pregnancy spacing women and couples are interested in the healthiest and health outcomes. The research objective was to time to become pregnant versus when to give birth. assess, from the best available evidence, the effects In this way, HTSP differs from previous birth of pregnancy spacing on maternal, newborn and spacing approaches that refer only to the interval child health outcomes. In June 2005, the World after a live birth and when to give birth. HTSP also Health Organization (WHO) convened a panel of 30 provides guidance on the healthiest age for the first technical experts to review six USAID-sponsored pregnancy. studies. Based on their review of the evidence, the technical experts made two recommendations* to the Thus, HTSP encompasses a broader concept of the WHO, which are included in a report and policy reproductive cycle starting from healthiest age for brief1: the first pregnancy in adolescents, to spacing subsequent pregnancies following a live birth, still • After a live birth, the recommended minimum birth, miscarriage or abortion – capturing all interval before attempting the next pregnancy is pregnancy-related intervals in a woman’s at least 24 months in order to reduce the risk of reproductive life. -

SPACING BIRTHS, SAVING LIVES Ways to Turn the Latest Birth Spacing Recommendation Into Results by Donna Espeut, Ph.D., M.H.S

SPACING BIRTHS, SAVING LIVES Ways to Turn the Latest Birth Spacing Recommendation into Results By Donna Espeut, Ph.D., M.H.S. Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS Specialist THE NEW BIRTH SPACING RECOMMENDATION Development (USAID) recommends birth intervals of three years or longer and recently For many years, family planning experts believed published Birth Spacing: A Call to Action that a 24-month birth interval (the amount of (available at http://www.usaid.gov/pop_health/ time between the birth date of one child and pop/publications/docs/birthspacing.pdf). The the birth date of the next child) was adequate to document summarizes research by Rutstein and ensure healthy mothers and healthy children. others, and discusses important considerations However, recent findings by Shea Rutstein, for action. UNICEF also Ph.D.1 indicate that spacing New Recommendation recognizes the need to promote births at least 36 months (three longer birth intervals. As part of years) apart is even more Births should be spaced at its Integrated Early Childhood 2 beneficial. least 36 months (three Development initiative (which In his analysis, Rutstein years) apart to achieve focuses on the first three years examined the association greater improvements in of life), UNICEF plans to work between birth intervals and child survival (see footnote with USAID and other partners various child health and number 2). to develop an action framework nutrition outcomes, including that promotes birth intervals of perinatal, infant, and under-five mortality.3 The at least three years for optimal health and analysis was conducted using MEASURE nutrition outcomes in children. DHS+ data from 17 less-developed countries. -

Birth Spacing at a Primary Spaced Pregnancies—A Study in Bangladesh Health Care Center in Kagoro, Nigeria

COMMENTARY Investing in Family Planning: Key to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Ellen Starbird,a Maureen Norton,a Rachel Marcusa Voluntary family planning brings transformational benefits to women, families, communities, and countries. Investing in family planning is a development ‘‘best buy’’ that can accelerate achievement across the 5 Sustainable Development Goal themes of People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership. INTRODUCTION and private commercial sectors, as well as through civil society. Family planning encompasses the services, policies, This paper outlines the multiple reasons why information, attitudes, practices, and commodities, investing in family planning is a good decision at every including contraceptives, that give women, men, level. It is aligned with recent studies that find that couples, and adolescents the ability to avoid unintended investing in family planning is a development ‘‘best pregnancy and choose whether and/or when to have a buy.’’1 Accordingly, we hope that the information ’ child. In this commentary, we outline family planning s presented here will help governments and planners— links to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and including Ministries of Finance, district health teams, highlight the transformational benefits that voluntary and civil society organizations—to consider family family planning brings to women, families, commu- planning as a fundamental element of any long-term, nities, and countries. We present family planning as a socioeconomic development strategy, and key to SDG cross-sectoral intervention that can hasten progress achievement. across the 5 SDG themes of People, Planet, Prosperity, In 2000, representatives from 189 United Nations Peace, and Partnership (Figure). We particularly stress Member States endorsed 8 Millennium Development ’ family planning s: Goals (MDGs) to be achieved by 2015, and affirmed Link to human rights, gender equality, and their collective commitment to poverty reduction and empowerment improved quality of life. -

Impacts of Healthy Birth Spacing in Jordan Photo Credit: © Othman Al Othman © Credit: Photo

The Impacts of Healthy Birth Spacing in Jordan Photo credit: © Othman Al May 2013 - Issa/Studio Robina Higher Population Council Presentation Outline Birth spacing and the Qur’an WHO recommendations and definition of intervals Benefits of healthy birth spacing Consequences of unhealthy birth spacing Relationship between birth intervals and health outcomes in Jordan Trends in birth spacing in Jordan Impacts of increasing birth intervals in Jordan Interventions to improve birth spacing in Jordan Birth Spacing and the Qur’an WHO Recommendations for Birth Spacing Recommendation for spacing after a live birth After a live birth, the recommended interval before attempting the next pregnancy is at least 24 months in order to reduce the risk of adverse maternal, perinatal, and infant outcomes. In simple terms, couples are encouraged to wait to attempt a new pregnancy until after the 2nd birthday of their last child. Recommendation for spacing after a miscarriage After a miscarriage, the recommended minimum time to wait to attempt another pregnancy is at least six months in order to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. World Health Organization (WHO). 2006. Report of a Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing, Geneva June 13–15, 2005. Geneva: WHO, Department of Making Pregnancy Safer and Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Definitions Recommended Birth-to-Birth and Birth-to-Pregnancy Intervals Birth-to-Birth Interval Period between two live births Birth-to-Pregnancy Interval Period between a live birth and the next pregnancy 24 months 9 months A 24-month birth-to-pregnancy interval is the approximate equivalent of a 33-month birth-to-birth interval.