Psychiatry CENTENNIAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Document Contains Summaries, Excerpts, Ideas And

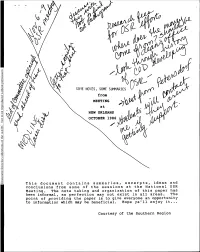

permission STIE NOTES, SOME SUMMARIES without from MEETING at reproduced be NEW ORLEANS to OCTOBER 1986 Not /' AAMC the of collections the from Document This document contains summaries, excerpts, ideas and conclusions from some of the sessions at the National OSR Meeting. The note taking and organization of this paper has been informal, so perfection may not exist in all areas. The point of providing the paper is to give everyone an opportunity to information which- may be beneficial. Hope ya'll enjoy it... Courtesy of the Southern Region Informal Notes/Outline on the GeneraL Session - Friday, October 24, 1986 Dr. Leon Eisenberg, Chairman Department of Social Medicine and Health Policy Harvard Medical School Dr. Leon Eisenberg spoke following his wife, Dr. Carola Eisenberg, who presented ideas about the "Light at the End of the Medical School Tunnel." Dr. Leon Eisenberg then talked about the Trains in the tunnel. I have taken the liberty to reorganize his talk to an outline form. ,1 ia-dittAzn 7iet 71_4.4 -NottetcOlthe-coriitiuttitiorWRAiorettcalicribbftWand. ta bwAsWmorkMicin-. 19.giVOleattlm1 4SW1.- r-40%. "INC FAP 90( GALLERY 2 Prf CARY-OIRSON Ntif IN PAPERBACK. DALE :21 THE TRAINS COST OF EDUCATION MALPRACTICE CRISIS Problem Possible Solution Problem Possible Solution -1. Trend is that the edit 1. Change the time allowed for I. Less than 302 of collected I. No-fault insurance will increase repayment of loans. funds, from a law suit go to the "injured party." 2. Fees charged when trivalent 2. Applicants will come from 2. Have a surcharge (of the cases are brought to court *families with higher debt) based on Income Tax 2. -

Save Pdf (0.14

In memoriam Leon Eisenberg and the essence of Medicine I got in touch with Leon Eisenberg at the very end of were thought to be a bit odd, you were called a ‘Section his long and fulfilling professional life, or, to be precise, 8’. Army psychiatrists concerned about the stigma he got in touch with me. On December 12th, 2006 I changed the terminology from “Section 8” to “Simple received a sharp and hilarious comment on a paper I had Adult Maladjustment”. Not long after the change was written on the change of the name “mental retardation” to made, the author of the editorial was in a base camp “intellectual disability” and its relation to stigma. In a watching a film starring Jerry Lewis. He was astonished friendly tone, it distilled joy of life and “bonheur”. The to hear members of the audience call out ‘Look at the author recalled an old editorial at the American Journal of ‘Sammy’. After a moment he realized that “Sammy” Psychiatry which explained that soldiers with neuropsy- stemmed from the initial letters “S.A.M.” of “Simple chiatric problems were classified under a code known as Adult Maladjustment”. ‘Section 8’ during the Second World War. “In no time at When I reached the end of the last line I was surprised all, this classification number spread throughout the mil- to find out that the author was Leon Eisenberg. By the itary community and became a term of derision. If you time I received this email, I had admired him for many Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 19, 1, 2010 93 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

Howland Award Presentation to Julius B. Richmond1

003 I-3998/90/2804-04 I 1$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 28, No. 4, 1990 Copyright 0 1990 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Prinled in (I.S. A. Howland Award Presentation to Julius B. Richmond1 LEON EISENBERG Chairman, Department of Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 I have known Julius B. Richmond for the better part of my Julie was called to Syracuse in 1953 to be the Chair of life-the better part qualitatively as well as quantitatively; having Pediatrics. He built an outstanding academic department. A him for a friend has made my life better. There isn't time to say portrait from this era of his life is shown in Figure 2. It presents all I would like to say about Julie. Moreover, if I said it all, it to us the 1961-62 Executive Committee of the Society for might be dangerous to his health. Julie has been known to Pediatric Research. Seated are Nathan Smith, J.B.R., the Vice respond to praise with an anaphylactic reaction. The only safe President, Fred Robbins, the President that year, Clark West, thing for me to do is to dispense my encomiums in homeopathic Forrest Adams, and Edna Sobel; standing are David Gitlin, Floyd doses. Denny, Lytt Gardner, and Sid Segal. There is no more telling way to put the accomplishments of Let me now abandon dating the strata in his academic prefer- his career in perspective than by recalling what Abraham Jacobi ment to scan his research career. I haven't the time and you said in his 1889 address as the first President of this Society. -

Some Children Are Convinced, They Can't Win

DOCUMENT' rSUM P: ED 021 892 UD 004 048 By- Eisenberg Leon SOME CHILDREN ARE CONVINCED, THEY CAN'TWig Pub Date Apr 67 Note- 5p Journal Cit- Southern Education Report; v2 n8 Apr1967 EDRS Price MF-S0.25 HC-$0.28 Descripters-*ACADEMIC FAILURE CHANGING ATTITUDES*CULTURAL DIFFERENCES *DISADVANTAGED YOUTK EDUCATIONAL NEEDS ENRICHMENT EXPERIENCEFAILURE FACTORS, FAMILY LIFE. INTELLIGENCE. INTERVENTIOR LANGUAGE HANDICAPS MIDDLE CLASSPRESCHOO L PROGRAMS. *SELF CONCEPT.TEACKER ATTITUDES Identifiers-Baltimore, Maryland, PrOiect Head Start Social dass differences affect a student'sacademic achievement but do not particularly affect his intellectual potential.Adult pdgement of intelligence isbased upon observationof the student's behavior and hisperformance on standardized tests. This behavior isin turn affected by thestudent's motivation, background experience, and attitudes. Thelower-dass child comes to school with afeding of personal inadequacy and because he lacksthe language skills and generalacademic know-how necessary in formal learning situations,he inevitably fails. Thus, there is perpetuated a cycle of frustration and fadure inwhich the child's academic deficits become cumulative. The experiences of aBaltimore Head Start Proiect haveshown that for the cyde to be broken thesechildren require a continuous enrichment program with warm, varied,- active,and flexible teachers. It is important, moreover,that the worthwhile aspects of the lower-classchild's own culture not be destroyed.inthe educational process, and that the school recognizehis language and learningstyles. (LB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION& WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCEDEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATINGIT. STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENTOFFICIAL OFFICE Of EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY SOME CHILDREN ARE CONVINCED THEY CAN'T WIN BY LEON EISENBERG, M.D. -

Leon Eisenberg Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Leon Eisenberg Address: 9 Clement Circle, Cambridge, MA 02138 Date of Birth: August 8, 1922 Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Office Telephone: 617-432-1710 Office Fax#: 617-432-2565 HMS-E-mail: [email protected] Earned Degrees: 1944 A.B. College of University of Pennsylvania 1946 M.D. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Honorary Degrees: 1967 A.M. (Hon) Harvard University 1973 D.Sc. (Hon) University of Manchester, England 1991 D.Sc. (Hon) University of Massachusetts Postdoctoral Training: Internship and Residencies: 1946-1947 Rotating Intern, Mt. Sinai Hospital, New York City 1950-1952 Psychiatric Resident, Sheppard Pratt Hospital, Towson, MD. 1952-1954 Fellow in Child Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD Military Service: 1948-1950 Captain, Medical Corps, U. S. Army Licensure and Certification: New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts 1955 (Dec) Certified in Psychiatry, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology 1960 (May) Certified in Child Psychiatry, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology Academic Appointments: 1947-1948 Instructor in Physiology, University of Pennsylvania 1953-1955 Instructor in Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University 1955-1958 Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University 1 1958-1961 Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University 1961-1967 Professor of Child Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University 1967-1993 Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School 1973-1980 Chairman, Executive Committee, Department of Psychiatry, -

An Editorial You Should

An Editorial You Should Read How dare we forget… The Autism Society of America’s founding mission, purpose, and objective can be summarized in one phrase: to discover and promulgate the truth about autism. The following editorial by Steven M. Edelstein, Ph.D., accurately chronicles autism’s challenging odyssey – what “truth about autism” we’ve learned and what we’ve done with it. This editorial is a must read for everyone in the autism community. Daniel A. Torisky Editorial: Stephen M. Edelson, Ph.D. Leo Kanner and 70 Years of Autism Reprinted with permission from Autism Research Review International, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2013, pp. 3,6. 2013 marks the 70th anniversary of the first paper to distinguish autism from other developmental disabilities. Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact was written by Leo Kanner, M.D., in 1943. The director of the first child psychiatry clinic (at Johns Hopkins Hospital), Kanner was considered by many to be the father of child psychiatry. His book Child Psychiatry (1935) was considered the premier textbook on child psychiatry for many years. In his 1943 article, Kanner eloquently described 11 children who were different from children with other disabilities, most notably those with childhood schizophrenia. He discussed their familial and developmental histories, as well as symptoms and behaviors. Kanner based his descriptions mostly on his in-depth interviews with parents. Leon Eisenberg, M.D., a colleague of Kanner, once wrote, “His interview with parents is remarkable for its capacity to elicit a sequential ac count of the vicissitudes of development. A sensitive listener, he rarely interrupts. -

Introduction. Deinstitutionalisation and the Pathways of Post-War Psychiatry in the Western World Despo Kritsotaki1, Vicky Long2 and Matthew Smith3

Introduction. Deinstitutionalisation and the Pathways of Post-War Psychiatry in the Western World Despo Kritsotaki1, Vicky Long2 and Matthew Smith3 1Department of History, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece 2Centre for the Social History of Health and Healthcare, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK 3Department of History, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK Near the small village of Gartcosh, located in the north-eastern quadrant of the greater Glasgow conurbation, there is an imposing two-towered gothic building that used to serve as the Main Administration Building of Gartloch Hospital. Surrounded by a fence, designed to keep people out, rather than to keep them in, its windows are either broken or boarded up. Inside, what is left of the floors is strewn with detritus, ranging from broken bits of furniture and torn curtains to crumbling plaster and bent nails. It is only when one looks up to the elaborate arched and buttressed ceiling, painted in shades of aquamarine, scarlet and vermillion, that a hint of the former grandeur of the place becomes apparent. Established in 1896 by the City of Glasgow and District Lunacy Board, Gartloch Hospital was one of dozens of Scottish psychiatric institutions built between the end of the eighteenth century and the middle of the twentieth century. It would exist for exactly 100 years, typically housing between 500 and 800 patients. Although it functioned primarily as a psychiatric facility for the city’s poor, as with similar institutions, it also served other functions, including a tuberculosis sanitaria soon after it opened, and as an Emergency Medical Services hospital during the First World War. -

“CHILDREN” by Amelia Buttress a Dissertation

THE CHEMICAL LIVES OF “CHILDREN” by Amelia Buttress A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2014 ABSTRACT Stimulants and ADHD have become nearly synonymous in recent decades. The now common practice of prescribing stimulants to children has fueled the long-standing controversy surrounding the legitimacy of what is commonly known as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The need to medically justify stimulant use has sharpened the debate between those who argue for the disorder’s medical validity and those who describe the disorder as a social construction. Historical inquiry into ADHD has maintained this dichotomy, retroactively fusing psycho-stimulants and children, and reifiing rather than challenging a false choice between medical and constructivist explanations of the disorder. This dissertation reexamines the significance of psychostimulants to two doctors in their work with children. Charles Bradley and Leon Eisenberg have, in recent years, figured prominently in historical accounts of ADHD as pioneering advocates of psychopharmalogical treatment of children with hyperactive and inattentive children, in particular with stimulants. Scholars have selectively mined the published works of these two doctors to either validate or contest a biomedical explanation of ADHD and, thus, the appropriateness of pharmacologic treatment. However, each man wrote during distict periods in American intellectual history, and their interpretation of the issues of the day influenced how they framed the results of their studies. A careful reading of the published works of Bradley and Eisenberg in light of their broader historical, intellectual and therapeutic contexts illuminates how both men derived a much wider range of uses for and i interpretations of stimulants as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for a range of children’s disorders. -

Winter Quarterly Meeting, 1986

BULLETIN OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS, VOL 10, MARCH 1986 65 Winter Quarterly Meeting, 1986 The Winter Quarterly Meeting and the Maudsley Bequest The Dependence/Addiction Group has applied for Lectures were held at The Royal Society, London SWI on Section status and this was approved by Council. Council 21 and 22 January 1986, under the Presidency of Dr has also accepted Guidelines prepared by the Section for Thomas Bewley. the Psychiatry of Mental Handicap on Consent to Medical and Surgical Treatment, Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion in the Mentally Handicapped. These will be Registrar's Report published in the Bulletin and are also available from the It is some two months since I presented my last Report, College on request. and in that time the Executive and Finance Committee has Council approved a proposal from the Special (Political met twice and Council once. Abuse of Psychiatry) Committee to set up a meeting with Our priority task at present is to prepare the College's other medical organisations to explore possible further response to the Mental Health Act 1983 Draft Code of action on Soviet abuse of psychiatry. This will be a closed Practice. Many of you will have seen this, a bulky docu meeting, but a summary of the proceedings will be pub ment of some 237 pages. I would like to spend a few lished. minutes explaining how the College will be collating the The President reported to Council on the progress of the response to this draft—adocument of extreme significance appeal to establish a permanent Research Unit at the which will affect the clinical practice, not only of our College. -

Inventor of ADHD's Deathbed Confession: "ADHD Is a Fictitious Di

Inventor Of ADHD's Deathbed Confession: "ADHD Is A Fictitious Di... http://www.worldpublicunion.org/2013-03-27-NEWS-inventor-of-adh... INVENTOR OF ADHD'S DEATHBED CONFESSION: "ADHD IS A - FEATURED ARTICLES - FICTITIOUS DISEASE" Wednesday, March 27th 2013 By Moritz Nestor, Current Concerns Source Mi piace 215mila 2,777 734 Fortunately, the Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics (NEK, President: Otfried Höffe) critically commented on the use of the ADHD drug Ritalin in its opinion of 22 November 2011 titled Human enhancement by means of pharmacological agents: The consumption of pharmacological agents altered the child’s behavior without any OPERATION CITIZEN'S ARREST contribution on his or her part. ANNOUNCED That amounted to interference in the child’s freedom and personal rights, We have become fully aware of criminal acts because pharmacological agents induced behavioral changes but failed to being committed by individuals and groups in educate the child on how to achieve these behavioral changes government and industry all over the world. independently. The child was thus deprived of an essential learning There is a vast criminal empire that has experience to act autonomously and emphatically which “considerably colluded to gain total control of resources, curtails children’s freedom and impairs their personality development”, the industry, finances, and life as we know it. We NEK criticized. know the truth, and we are no longer going to take it anymore. People of the world united! The alarmed critics of the Ritalin -

The Illusions of Psychiatry Marcia Angell the New York Review of Books - June 23, 2011 Part 2 of a Two-Part Article

The Illusions of Psychiatry Marcia Angell The New York Review of Books - June 23, 2011 Part 2 of a two-part article In Part 1 of my article in the last issue, I focused mainly on the recent books by psychologist Irving Kirsch and journalist Robert Whitaker, and what they tell us about the epidemic of mental illness and the drugs used to treat it. Here I discuss the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—often referred to as the bible of psychiatry, and now heading for its fifth edition in 2013—and its extraordinary influence within American society. I also examine Unhinged, the recent book by Daniel Carlat, a psychiatrist, who provides a disillusioned insider’s view of the psychiatric profession. And I discuss the widespread use of psychoactive drugs in children, and the baleful influence of the pharmaceutical industry on the practice of psychiatry. One of the leaders of modern psychiatry, Leon Eisenberg, a professor at Johns Hopkins and then Harvard Medical School, who was among the first to study the effects of stimulants on attention deficit disorder in children, wrote that American psychiatry in the late twentieth century moved from a state of “brainlessness” to one of “mindlessness.”2 By that he meant that before psychoactive drugs (drugs that affect the mental state) were introduced, the profession had little interest in neurotransmitters or any other aspect of the physical brain. Instead, it subscribed to the Freudian view that mental illness had its roots in unconscious conflicts, usually originating in childhood that affected the mind as though it were separate from the brain. -

Interview with Sir Michael Rutter

Clinical Perspectives Interview with Sir Michael Rutter (interviewed by Normand Carrey, MD, June 9th 2010) t is no exaggeration to say that Sir Michael Rutter stands alone, Q. Tell me about internship, residency? Ioccupying that rarefied position as the top leader in child psy- chiatry. His accomplishments are many and his influence extends A. I did some psychiatry as an intern in conjunction with neu- beyond child psychiatry to other disciplines such as education, rology and neurosurgery. As a medical student I had a period psychology, pediatrics and social work. However, in addition to working with Professor Mayer-Gross, one of the major figures his scholarliness, his devotion to hard work and his intellectual of German Psychiatry, who fled Nazi Germany because of his rigor, it is also his personal qualities of modesty and utter devo- Jewish heritage. He was a wonderful teacher. I had vivid memo- tion to improving the lives of children that were so compelling ries of my first case presentation to him. throughout this interview. The two and a half hours spent with He had me interview one of the psychiatry patients from the back him had a profound impact on me and although I would say the wards but I could not make heads or tails out of this patient. In my man is as close as we can get to a living saint, he would severely presentation to him I said, “I’m sorry but I’ve completely failed chide me for straying away from the data at hand. you”. I was really convinced that I had entirely botched up the interview.