Management of Airway Obstruction and Stridor in Pediatric Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxygen and Oxygen Equipment Local Coverage Determination (LCD)

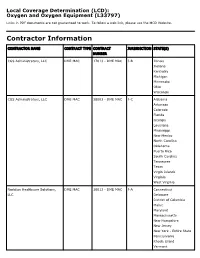

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Oxygen and Oxygen Equipment (L33797) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER CGS Administrators, LLC DME MAC 17013 - DME MAC J-B Illinois Indiana Kentucky Michigan Minnesota Ohio Wisconsin CGS Administrators, LLC DME MAC 18003 - DME MAC J-C Alabama Arkansas Colorado Florida Georgia Louisiana Mississippi New Mexico North Carolina Oklahoma Puerto Rico South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virgin Islands Virginia West Virginia Noridian Healthcare Solutions, DME MAC 16013 - DME MAC J-A Connecticut LLC Delaware District of Columbia Maine Maryland Massachusetts New Hampshire New Jersey New York - Entire State Pennsylvania Rhode Island Vermont CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, DME MAC 19003 - DME MAC J-D Alaska LLC American Samoa Arizona California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Idaho Iowa Kansas Missouri - Entire State Montana Nebraska Nevada North Dakota Northern Mariana Islands Oregon South Dakota Utah Washington Wyoming LCD Information Document Information LCD ID Original Effective Date L33797 For services performed on or after 10/01/2015 LCD Title Revision Effective Date Oxygen and Oxygen Equipment For services performed on or after 08/02/2020 Proposed LCD in Comment Period Revision Ending Date N/A N/A Source Proposed LCD Retirement Date DL33797 N/A AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Notice Period Start Date Statement 06/18/2020 CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All Rights Notice Period End Date Reserved. -

Chronic Cough, Shortness of Breathe, Wheezing? What You Should

CHRONIC COUGH, SHORTNESS OF BREATH, WHEEZING? WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT COPD. A quick guide on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease COPD.nhlbi.nih.gov COPD, or chronic obstructive Most often, COPD occurs in people pulmonary disease, is a serious lung age 40 and over who… disease that over time makes it hard • Have a history of smoking to breathe. Other names for COPD include • Have had long-term exposure to lung irritants chronic bronchitis or emphysema. such as air pollution, chemical fumes, or dust from the environment or workplace COPD, a leading cause of death, • Have a rare genetic condition called alpha-1 affects millions of Americans and causes antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency long-term disability. • Have a combination of any of the above MAJOR COPD RISK FACTORS history of SMOKING AGE 40+ RARE GENETIC CONDITION alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency LONG-TERM exposure to lung irritants WHAT IS COPD? To understand what COPD is, we first The airways and air sacs are elastic (stretchy). need to understand how respiration When breathing in, each air sac fills up with air like and the lungs work: a small balloon. When breathing out, the air sacs deflate and the air goes out. When air is breathed in, it goes down the windpipe into tubes in the lungs called bronchial In COPD, less air flows in and out of tubes or airways. Within the lungs, bronchial the airways because of one or more tubes branch into thousands of smaller, thinner of the following: tubes called bronchioles. These tubes end in • The airways and air sacs lose bunches of tiny round air sacs called alveoli. -

Guía Práctica Clínica Bronquiolitis.Indd

Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Bronchiolitis CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN THE SPANISH NATIONAL HEALTHCARE SYSTEM MINISTRY FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL POLICY It has been 5 years since the publication of this Clinical Practice Guideline and it is subject to updating. Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Bronchiolitis It has been 5 years since the publication of this Clinical Practice Guideline and it is subject to updating. CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN THE SPANISH NATIONAL HEALTHCARE SYSTEM MINISTRY FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL POLICY This CPG is an aid for healthcare decisions. It is not binding, and does not replace the clinical judgement of healthcare staff. Published: 2010 It has beenPublished 5 years by: Ministry since for theScience publication and Innovation of this Clinical Practice Guideline and it is subject to updating. NIPO (Official Publication Identification No.): 477-09-055-4 ISBN: pending Legal depository: B-10297-2010 Printed by: Migraf Digital This CPG has been funded via an agreement entered into by the Carlos III Health Institute, an autonomous body within the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation, and the Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment, within the framework for cooperation established in the Quality Plan for the Spanish National Healthcare System of the Spanish Ministry for Health and Social Policy. This guideline must be cited: Working Group of the Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Bronchiolitis; Sant Joan de Déu Foundation Fundació Sant Joan de Déu, coordinator; Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Bronchiolitis; Quality Plan for the Spanish National Healthcare System of the Spanish Ministry for Health and Social Policy; Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment, 2010; Clinical Practice Guidelines in the Spanish National Healthcare System: CAHTA no. -

Inhalation of “Borax”

Journal of Paediatrics and Neonatal Disorders Volume 4 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2456-5482 Case Report Open Access Inhalation of “Borax” and Risk of Severe Stridor Obaid O* Department of Pediatrics, MOH, Makkah, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding author: Obaid O, Department of Pediatrics, MOH, Makkah, Saudi Arabia, Tel: 00966500606352, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Obaid O (2019) Inhalation of “Borax” and Risk of Severe Stridor. J Paedatr Neonatal Dis 4(1): 105 Received Date: March 21, 2019 Accepted Date: June 26, 2019 Published Date: June 28, 2019 Abstract Stridor in children is not uncommon reason to visit emergency department and usually due to croup but inhalation of toxic substance may cause severe stridor which is uncommon. Keywords: Stridor; Pediatric; Sodium Burate Case Report A 9 year old Saudi girl presented to emergency department accompanied by her grandmother with history of dry cough, shortness of breath and audible wheeze for more than12 hours. She has no history of fever, foreign body ingestion and chronic cough. No history of contact with sick person and no history of lip swelling or skin rash. Her vaccination status up to date. She was a Preterm 30 weeks, admitted to Neonatal intensive care for 2 months and discharge well. In emergency room she was ill looking with biphasic stridor, kept on oxygen 10 liter/min and given one dose IM epinephrine 0.3 mg and nebulizer Racemic epinephrine, connected to Cardiorespiratory monitor and 2 IV lines was inserted started on IV Fluids and given one dose of dexamethasone. Urgent consultation to ENT was done and they recommend bronchoscopy to rule out Foreign body ingestion. -

Domestic Violence: the Shaken Adult Syndrome

138 J Accid Emerg Med 2000;17:138–139 J Accid Emerg Med: first published as 10.1136/emj.17.2.139 on 1 March 2000. Downloaded from CASE REPORTS Domestic violence: the shaken adult syndrome T D Carrigan, E Walker, S Barnes Abstract Her initial blood pressure was 119/72 mm A case of domestic violence is reported. Hg, pulse 88 beats/min, her pupils were equal The patient presented with the triad of and reactive directly and consensually, and her injuries associated with the shaking of Glasgow coma score was 13/15 (she was infants: retinal haemorrhages, subdural confused and was opening her eyes to com- haematoma, and patterned bruising; this mand). Examination of the head showed bilat- has been described as the shaken adult eral periorbital ecchymoses, nasal bridge swell- syndrome. This case report reflects the ing and epistaxis, a right frontal abrasion, and diYculties in diagnosing domestic vio- an occipital scalp haematoma. Ecchymoses lence in the accident and emergency were also noted on her back and buttocks, setting. being linear in fashion on both upper arms, (J Accid Emerg Med 2000;17:138–139) and her underpants were torn. Initial skull and Keywords: domestic violence; women; assault facial x ray films were normal, and she was admitted under the care of A&E for neurologi- cal observations. Domestic violence is an under-reported and Over the next 24 hours, her Glasgow coma major public health problem that often first score improved to 15/15, but she had vomited presents to the accident and emergency (A&E) five times and complained that her vision department. -

Prilocaine Induced Methemoglobinemia Güzelliğin Bedeli; Prilokaine Bağlı Gelişen Methemoglobinemi Olgusu

CASE REPORT 185 Cost of Beauty; Prilocaine Induced Methemoglobinemia Güzelliğin Bedeli; Prilokaine Bağlı Gelişen Methemoglobinemi Olgusu Elif KILICLI, Gokhan AKSEL, Betul AKBUGA OZEL, Cemil KAVALCI, Dilek SUVEREN ARTUK Department of Emergency Medicine, Baskent University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara SUMMARY ÖZET Prilocaine induced methemoglobinemia is a rare entity. In the pres- Prilokaine bağlı gelişen methemoglobinemi nadir görülen bir du- ent paper, the authors aim to draw attention to the importance of rumdur. Bu yazıda epilasyon öncesi kullanılan prilokaine sekonder this rare condition by reporting this case. A 30-year-old female gelişen methemoglobinemi olgusunu sunarak nadir görülen bu presented to Emergency Department with headache, dispnea and durumun önemine işaret etmek istiyoruz. Otuz yaşında kadın acil cyanosis. The patient has a history of 1000-1200 mg of prilocaine servise baş ağrısı, dispne ve siyanoz şikayetleri ile başvurdu. Hasta- ya beş saat öncesinde bir güzellik merkezinde epilasyon öncesinde subcutaneous injection for hair removal at a beauty center, 5 hours yaklaşık 1000-1200 mg prilokain subkutan enjeksiyonu yapıldığı ago. Tension arterial: 130/73 mmHg, pulse: 103/minute, body tem- öğrenildi. Başvuruda kan basıncı 130/73 mmHg, nabız 103/dk, vü- perature: 37 °C and respiratory rate: 20/minute. The patient had ac- cut ısısı 37 °C ve solunum sayısı 20/dk olarak kaydedilmişti. Hasta- ral and perioral cyanosis. Methemoglobin was measured 14.1% in nın akral siyanozu belirgindi. Venöz kan gazında methemoglobin venous blood gas test. The patient treated with 3 gr ascorbic acid düzeyi %14.1 olarak ölçüldü. Hastaya 3 g intravenöz askorbik asit intravenously. The patient was discharged free of symptoms after uygulandı. -

Supraglottoplasty Home Care Instructions Hospital Stay Most Children Stay Overnight in the Hospital for at Least One Night

10914 Hefner Pointe Drive, Suite 200 Oklahoma City, OK 73120 Phone: 405.608.8833 Fax: 405.608.8818 Supraglottoplasty Home Care Instructions Hospital Stay Most children stay overnight in the hospital for at least one night. Bleeding There is typically very little to no bleeding associated with this procedure. Though very unlikely to happen, if your child were to spit or cough up blood you should contact your physician immediately. Diet After surgery your child will be able to eat the foods or formula that they usually do. It is important after surgery to encourage your child to drink fluids and remain hydrated. Daily fluid needs are listed below: • Age 0-2 years: 16 ounces per day • Age 2-4 years: 24 ounces per day • Age 4 and older: 32 ounces per day It is our experience that most children experience a significant improvement in eating after this procedure. However, we have found about that approximately 4% of otherwise healthy infants may experience a transient onset of coughing or choking with feeding after surgery. In our experience these symptoms resolve over 1-2 months after surgery. We have also found that infants who have other illnesses (such as syndromes, prematurity, heart trouble, or other congenital abnormalities) have a greater risk of experiencing swallowing difficulties after a supraglottoplasty (this number can be as high as 20%). In time the child usually will return to normal swallowing but there is a small risk of feeding difficulties. You will be given a prescription before you leave the hospital for an acid reducing (anti-reflux) medication that must be filled before you are discharged. -

Stridor in the Newborn

Stridor in the Newborn Andrew E. Bluher, MD, David H. Darrow, MD, DDS* KEYWORDS Stridor Newborn Neonate Neonatal Laryngomalacia Larynx Trachea KEY POINTS Stridor originates from laryngeal subsites (supraglottis, glottis, subglottis) or the trachea; a snoring sound originating from the pharynx is more appropriately considered stertor. Stridor is characterized by its volume, pitch, presence on inspiration or expiration, and severity with change in state (awake vs asleep) and position (prone vs supine). Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of neonatal stridor, and most cases can be managed conservatively provided the diagnosis is made with certainty. Premature babies, especially those with a history of intubation, are at risk for subglottic pathologic condition, Changes in voice associated with stridor suggest glottic pathologic condition and a need for otolaryngology referral. INTRODUCTION Families and practitioners alike may understandably be alarmed by stridor occurring in a newborn. An understanding of the presentation and differential diagnosis of neonatal stridor is vital in determining whether to manage the child with further observation in the primary care setting, specialist referral, or urgent inpatient care. In most cases, the management of neonatal stridor is outside the purview of the pediatric primary care provider. The goal of this review is not, therefore, to present an exhaustive review of causes of neonatal stridor, but rather to provide an approach to the stridulous newborn that can be used effectively in the assessment and triage of such patients. Definitions The neonatal period is defined by the World Health Organization as the first 28 days of age. For the purposes of this discussion, the newborn period includes the first 3 months of age. -

Shanti Bhavan Medical Center Biru, Jharkhand, India

Shanti Bhavan Medical Center Biru, Jharkhand, India We Care, He Heals Urgent Needs 1. Boundary Wall around the hospital property Cost: $850,000 In India any land (even owned) can be taken by the government at any time if there is not boundary wall around it. Our organization owns property around the hospital that is intended for the Nursing school and other projects. We need a boundary wall built around the land so that the government can’t recover the land. 2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Device Cost: $300,000 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to form pictures of the anatomy and the physiological processes of the body in both health and disease. MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields, radio waves, and field gradients to generate images of the organs in the body. 3. Kidney Stone Lipotriptor Cost: $200,000 Kidney Stone Lipotriptor Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) is the least invasive surgical stone treatment using high frequency sound waves from an external source (outside the body) to break up kidney stones into smaller pieces, and allow them to pass out through the urinary tract. 4. Central Patient Monitoring System Cost: $28,000 Central Patient Monitoring System- A full-featured system that provides comprehensive patient monitoring and review. Monitors up to 32 patients using two displays and is ideal for telemetry, critical care, OR, emergency room, and other monitoring environments. Provides data storage and review capabilities, and ensures a complete patient record by facilitating automated patient and data transfer between multiple departments. 5. ABG Machine Cost: $25,000 ABG machine- An arterial blood gas test (ABG) is a blood gas test of blood taken from an artery that measures the amounts of certain gases (such as oxygen and carbon diox- ide) dissolved in arterial blood. -

Snoring and Stertor Are Associated with More Sleep Disturbance Than Apneas and Hypopneas in Pediatric SDB

Sleep and Breathing (2019) 23:1245–1254 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01809-3 SLEEP BREATHING PHYSIOLOGY AND DISORDERS • ORIGINAL ARTICLE Snoring and stertor are associated with more sleep disturbance than apneas and hypopneas in pediatric SDB Mark B. Norman1 & Henley C. Harrison2 & Karen A. Waters1,3 & Colin E. Sullivan1,3 Received: 2 November 2018 /Revised: 26 January 2019 /Accepted: 19 February 2019 /Published online: 1 March 2019 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Purpose Polysomnography is not recommended for children at home and does not adequately capture partial upper airway obstruction (snoring and stertor), the dominant pathology in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. New methods are required for assessment. Aims were to assess sleep disruption linked to partial upper airway obstruction and to evaluate unattended Sonomat use in a large group of children at home. Methods Children with suspected obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) had a single home-based Sonomat recording (n = 231). Quantification of breath sound recordings allowed identification of snoring, stertor, and apneas/hypopneas. Movement signals were used to measure quiescent (sleep) time and sleep disruption. Results Successful recordings occurred in 213 (92%) and 113 (53%) had no OSA whereas only 11 (5%) had no partial obstruc- tion. Snore/stertor occurred more frequently (15.3 [5.4, 30.1] events/h) and for a longer total duration (69.9 min [15.7, 140.9]) than obstructive/mixed apneas and hypopneas (0.8 [0.0, 4.7] events/h, 1.2 min [0.0, 8.5]); both p < 0.0001. Many non-OSA children had more partial obstruction than those with OSA. -

INITIAL APPROACH to the EMERGENT RESPIRATORY PATIENT Vince Thawley, VMD, DACVECC University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

INITIAL APPROACH TO THE EMERGENT RESPIRATORY PATIENT Vince Thawley, VMD, DACVECC University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA Introduction Respiratory distress is a commonly encountered, and truly life-threatening, emergency presentation. Successful management of the emergent respiratory patient is contingent upon rapid assessment and stabilization, and action taken during the first minutes to hours often has a major impact on patient outcome. While diagnostic imaging is undoubtedly a crucial part of the workup, patients at presentation may be too unstable to safely achieve imaging and clinicians may be called upon to institute empiric therapy based primarily on history, physical exam and limited diagnostics. This lecture will cover the initial evaluation and stabilization of the emergent respiratory patient, with a particular emphasis on clues from the physical exam that may help localize the cause of respiratory distress. Additionally, we will discuss ‘cage-side’ diagnostics, including ultrasound and cardiac biomarkers, which may be useful in the working up these patients. Establishing an airway The first priority in the dyspneic patient is ensuring a patent airway. Signs of an obstructed airway can include stertorous or stridorous breathing or increased respiratory effort with minimal air movement heard when auscultating over the trachea. If an airway obstruction is present efforts should be made to either remove or bypass the obstruction. Clinicians should be prepared to anesthetize and intubate patients if necessary to provide a patent airway. Supplies to have on hand for difficult intubations include a variety of endotracheal tube sizes, stylets for small endotracheal tubes, a laryngoscope with both small and large blades, and instruments for suctioning the oropharynx. -

How Is Pulmonary Fibrosis Diagnosed?

How Is Pulmonary Fibrosis Diagnosed? Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) may be difficult to diagnose as the symptoms of PF are similar to other lung diseases. There are many different types of PF. If your doctor suspects you might have PF, it is important to see a specialist to confirm your diagnosis. This will help ensure you are treated for the exact disease you have. Health History and Exam Your doctor will perform a physical exam and listen to your lungs. • If your doctor hears a crackling sound when listening to your lungs, that is a sign you might have PF. • It is also important for your doctor to gather detailed information about your health. ⚪ This includes any family history of lung disease, any hazardous materials you may have been exposed to in your lifetime and any diseases you’ve been treated for in the past. Imaging Tests Tests like chest X-rays and CT scans can help your doctor look at your lungs to see if there is any scarring. • Many people with PF actually have normal chest X-rays in the early stages of the disease. • A high-resolution computed tomography scan, or HRCT scan, is an X-ray that provides sharper and more detailed pictures than a standard chest X-ray and is an important component of diagnosing PF. • Your doctor may also perform an echocardiogram (ECHO). ⚪ This test uses sound waves to look at your heart function. ⚪ Doctors use this test to detect pulmonary hypertension, a condition that can accompany PF, or abnormal heart function. Lung Function Tests There are several ways to test how well your lungs are working.