M.Venkatarangaiya Foundation an Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siddapur a Model Village in Making Meet the Field Assistant Subba Rao

n an attempt to engage and educate students The social map helps in identifying households based about the rural space, the National Coun- on predefined indicators relating to socio-econom- Icil of Rural Institutes (NCRI) in collabora- ic conditions ( status, skills, property, education, in- tion with University of Hyderabad (UoH) con- come). The population’s well being is then ranked (by ducted a 48-hour Rural Immersion Camp (RIC) those living there)identifying as to which household is from 1st to 3rd September in 10 selected vil- better or worse off in terms of the selected indicators. lages from Rangareddy District of Telangana. The Resource map helps in identifying nat- 195 students belonging to various streams from the ural resources in the locality and it de- Centre for Integrated Studies (CIS) participated in this picts land, hills, rivers, fields and vegetation. camp. These students were formed into 10 groups guid- A resource map in PRA is not drawn to scale. It is ed by a resource person from NCRI. Under mentorship done with the support of the local people as they of the resource person from the Council, the Participa- have an in-depth and detailed knowledge of the sur- tory Rural Appraisal (PRA) exercise was conducted in roundings where they are living there for a long time. these villages with an aim to understand and experience Seasonality map helps to identify heavy workload pe- rural India. On day one, a Transect Walk was conducted, riods, periods of relative ease, credit crunch, diseas- during which the students walked along with the villagers es, food security and wage availability. -

OU MBA Hyderabad Colleges

LIST OF AFFILIATED COLLEGES UNDER OSMANIA UNIVERSITY OFFERING MBA COURSE FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2010-2011 S.No Name of the College 1. A.V. College of Arts, Science, Commerce, Gaganmahal, Hyderabad -500 029. 2. Aurora’s Management & Research Institute, (formerly Aurora’s P.G.College), Parvathapur (V), Ghatkesar (M), Ranga Reddy Dist. 3. Avanthi P.G.College, No.16-11-741/B/1/A, Mooarambagh, Dilsukhnagar, Hyderabad – 500 036 4. Azad Institute of Management, Padmangalaram (V), Moinabad (M), Ranga Reddy Dist.. 5. Al-Quarmoshi Institute of Business Management, 18-11-26/7, Jamal Banda, Barkas, Hyderabad – 500 005. 6. Anwar-Ul-Uloom College of Business Management, 11-3-918, New Mallepaly, Hyderabad – 500 001. 7. Badruka College PG Centre, Kachiguda, Hyderabad - 500 027 8. Bright Institute of Management, Manimuthyalamma Kunta, Turka Yamjal, Hayathnagar (M) Ranga Reddy Dist. - 501 510. 9. Bharat P.G.College for Women, Opp.Tourist Hotel, Kachiguda, Hyderabad – 500 027. 10. Bharathiya Vidya Bhawans Vivekananda College of Science, Humanities & Commerce, Sainikpuri, Secunderabad - 500 094. 11. Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of Technology,Chaitanya Bharathi Post, Gandipet,Hyderabad – 500 075 12. Aurora’s School of Business(formerly Church P.G.College), Plot No. 15,Amaravathi Co-op. Society Colony, Bowenpally, Secunderabad 13. DVR P.G. Institute of Management Studies,1-98-5-2, Vital Rao Nagar, Madhapur,Hyderabad – 500 081. 14. Deccan School of Management, Near Darus- salam, Nampally, Hyderabad – 500 001. 15. David Memorial Institute of Management, 12-13-1275,Tarnaka, Secunderabad - 500 017. 16. Einstein College of Business Management(formerly Einstein P.G.College), Nadargul, Saroornagar (M), Ranga Reddy District - 501 510 17. -

Details of Blos Appointed in Respect of Mahabub Nagar - Ranga Reddy - Hyderabad Graduates' Constituency

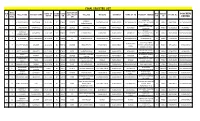

Details of BLOs appointed in respect of Mahabub Nagar - Ranga Reddy - Hyderabad Graduates' Constituency BLO Details Sl. Part Location of Building in which it will be District Name Polling Area No. No. Polling Station located Mobile Name of the BLO Designation Number 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 Zilla Parishad High School (S.Block) Village Revenue 1 Mahabubnagar 1 Koilkonda Entire Koilkonda Mandal B. Gopal 6303174951 Middle Room No.1 Assistant Zilla Parishad High School (S.Block) Village Revenue 2 Mahabubnagar 2 Koilkonda Entire Koilkonda Mandal B. Suresh 6303556670 Middle Room No.2 Assistant Govt., High School, Hanwada Ex Village Revenue 3 Mahabubnagar 3 Hanwada Hanwada Mandal J SHANKAR 9640619405 Mandal, Room No.2 Officer Govt., High School, Hanwada Ex Village Revenue 4 Mahabubnagar 4 Hanwada Hanwada Mandal K RAVINDAR 9182519739 Officer Mandal, Room No.3 Village Revenue 5 Mahabubnagar 5 Nawabpet ZPHS (Room No.1) Nawabpet Mandal S.RAJ KUMAR 9160331433 Assistant Village Revenue 6 Mahabubnagar 6 Nawabpet ZPHS (Room No.2) Nawabpet Mandal V SHEKAR 9000184469 Assistant Village Revenue 7 Mahabubnagar 7 Balanagar Mandal Primary School Balanagar Mandal B.Srisailam 9949053519 Assistant Village Revenue 8 Mahabubnagar 8 Rajapur ZPHS (Room No.1) Rajapur Mandal K.Ramu 9603656067 Assistant Ex Village Revenue 9 Mahabubnagar 9 Midjil ZPHS (Room No.2) Midjil Mandal SATYAM GOUD 9848952545 Officer Zilla Parishad High School Village Revenue 10 Mahabubnagar 10 Badepally Jadcherla Rural Villages SATHEESH 8886716611 (Boys), Room No.1 Assistant Zilla Parishad High School Village Revenue 11 Mahabubnagar 11 Badepally Jadcherla Rural Villages G SRINU 996303029 (Boys), Room No.2 Assistant Zilla Parishad High School Jadcherla Grama Village Revenue 12 Mahabubnagar 12 Badepally R.ANJANAMMA 9603804459 (Boys), Room No.3 Panchayath Paridhi Assistant 1 Details of BLOs appointed in respect of Mahabub Nagar - Ranga Reddy - Hyderabad Graduates' Constituency BLO Details Sl. -

Government of India Ministry of Commerce & Industry

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE) RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 221 TO BE ANSWERED ON 23rd JULY 2014 NON-FUNCTIONING SEZs *221. SHRI AMBETH RAJAN: Will the Minister of COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY be pleased to state: a) the details of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), name and their developers, which have not started functioning despite approval given by Government; b) the reasons for their not starting functioning and period for which they are lying non- operational; c) the details of the loss of revenue to Government due to non-functioning of SEZs, for whom land and other tax sops were given; and d) the action taken by Government in this regard? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY(INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SMT. NIRMALA SITHARAMAN) a) to d): A Statement is laid on the Table of the House. STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) TO (d) OF RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 221 FOR ANSWER ON 23rd JULY, 2014 REGARDING “NON- FUNCTIONING SEZs” (a): The details of approved non-functional Special Economic Zones (SEZs) is at Annexure. (b): Setting up of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) is a long term process and time for completion of project depends on several issues. The reasons for not being able to operationalise the SEZs include changed fiscal incentive regime for SEZs, difficulty in achieving contiguity of land, global recession, delay in approvals from statutory/State Government bodies and delay in environmental clearance, etc. (c): The SEZ is cancelled/de-notified subject to payment of all applicable duties and tax benefits availed by the Developer and receipt of No-objection Certificate (NOC) from the concerned State Government. -

CGR Newsletter February 2021.Pdf

CGR’S CNN NATURE NEWS Vol. 3, No.5 February 2021 Editorial Congratulations to Joe Biden who took oath as the 46th President of the United States and Kamala Harris sworn in as the nation's first female Vice-President and person of South Asian descent to hold the role. We look forward that the new administration will have a positive vision towards environmental protection and caring perspective for mother earth. As the most influential nation, US will have major impact on the outlook of all other nations towards climate change, sustainable development. We wish a new paradigm sets in for earth system governance. Many countries approved covid vaccine and started vaccination. We hope that it will be effective to counter the challenge from the pandemic. Farmers protest continues and somewhat disturbing incidents took place in Delhi on republic day. We wish soon a convincing solution will resolve the issue. Earth Centre is at the finishing stage. As a culmination to the competitions on rural primary health, holistic education and digital Inside… earth reel CGR organized webinars and Webinar on rural primary health 2 unveiled the results in the presence of Unveiling of digital earthreel 3 renowned personalities. A plantation Webinar on holistic school education 4 programme was facilitated for Palle Palle Prakruthivanam at Ekkareddyguda 5 Prakruthivanam at Ekkareddyguda in Chevalla Other updates 6 mandal. Eastern Ghats Environment Outlook World Wetlands Day 9 book was dispatched to all the Member of Ansel Adams 10 Parliament in the region. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 CGR’s Nature News Vol. 3, No. 5 February 2021 (No.29) Webinar on rural primary health Hyderabad, Second year Medico Health is the most important indicator of respectively. -

In the High Court of Karnataka at Bengaluru

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 28 TH DAY OF APRIL 2016 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE S. ABDUL NAZEER WRIT PETITION NOS.25884-25931/2016 (EDN-RES) Between: 1. PADMAPRIYA D.Ed. COLLEGE GANDHI NAGAR, BANGARAPET, KOLAR DISTRICT, REPRESENTED BY PURUSHOTHAMAN, AGED ABOUT 60 YEARS, RESIDING AT NO. 1170, 5TH MAIN, SUMATHINAGAR, ROBERTSONPET, KOLAR GOLD FIELDS-563 122, BANGARAPET TALUK, KOLAR DISTRICT. 2. TANKARA SRAVANTHI D/O. T. VENKAT RAMULU, AGED ABOUT 21 YEARS, R/AT VEPOOR VILLAGE, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE. 3. Y. SUNNY S/O. YESUDASS, AGED ABOUT 32 YEARS, R/AT KOTHALAPAD VILLAGE, KOIL GUNDA MANDAL, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE. 2 4. ERRAGOLA MALLESHWARI D/O. ERRAGOLA VENKATAIAH, AGED ABOUT 22 YEARS, R/AT GONAKOTTAPALLY VILLAGE, HANWADA MANDAL, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE. 5. PATLAVATH KISHAN S/O. PATLAVATH PURYA, AGED ABOUT 22 YEARS, R/AT GANDED VILLAGE, RANGA REDDY DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE. 6. CHINNAMALLA SAI BABA S/O. SAILU, AGED ABOUT 22 YEARS, R/AT GANDED VILLAGE, RANGA REDDY DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE. 7. S. MARIYAMMA D/O. S. BALAIAH, AGED ABOUT 22 YEARS, R/AT THIRUMALAGIRI VILLAGE, BALA NAGAR MANDAL, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE-509 408. 8. M. RAJESHWARI D/O. BALAIAH, AGED ABOUT 23 YEARS, R/AT HOUSE NO. 2-75, NEAR POST OFFICE, ADDAKAL VILLAGE, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE-509 382. 9. KUMBA VARALAXMI D/O. KUMBA SHANTAIAH, AGED ABOUT 24 YEARS, R/AT D. NO. 2-75, NEAR POST OFFICE, ADDAKAL VILLAGE, MAHABOOB NAGAR DISTRICT, TELANGANA STATE-509 382. 3 10. CHITTAMONI BHARGAVI D/O. -

Final Selected List

FINAL SELECTED LIST HALL EDUCATION SI.N DATE OF COMM GEND MAR RELIGI COACHING TICKE FULL NAME FATHER NAME QUALIFICATI VILLAGE MANDAL DISTRICT NAME OF PS PRESENT ADDERS PHONE NO O BIRTH UNITY ER KS ON T NO. ON CENTRE H NO: 1-5- BUDWEL, 1 1 G SHANTHIPRIYA G RATHNAM 31.08.1994 SC FEMALE DEGREE RAJENDRANAGAR RANGAREDDY RAJENDRANAGAR 107,BUDWEL,RAJENDRA 29 HINDU 9948379981 RAJENDRANAGAR RAJENDRANGAR NAGAR ENKAPALLY VILLAGE, 2 2 T. ANURADHA NARSHIMULU 09.09.1996 SC FEMALE DEGREE ENKAPALLY MOINABAD RANGAREDDY MOINABAD 25 HINDU 8790269626 MOINABAD MOINABAD H NO: 3- JAMMULA 3 3 J RAMREDDY 14.06.1997 OC FEMALE DEGREE CHENGICHERLA GHATKESAR RANGAREDDY MEDIPALLY 74/1/10,CHENGICHERLA 28 HINDU 7013428308 RAJENDRANAGAR NAVEENA REDDY ,GATKESAR 4 4 S. MANEELA LATE CHANDRAIAH 11.11.1996 SC FEMALE PG RAJENDRANAGAR RAJENDRANAGAR RANGAREDDY RAJENDRANAGAR RAJENDRANGAR 23 HINDU 9701226749 RAJENDRANAGAR H NO:1-60, PEDDA SHAMSHABAD 5 5 DASARI PADMAJA MALLESH 10.10.1990 BC FEMALE DEGREE PEDDATHUPRA SHAMSHABAD RANGAREDDY THUPRA ,SHAMSHABAD 36 HINDU 7659847103 SHAMSHABAD RURAL MANDAL, RR DIST NAGIREDDIGUDEM, 6 7 SMT.T.UMARANI SRIKANTH 01.05.1994 SC FEMALE INTER NAGIREDIGUDAM MOINABAD RANGAREDDY MOINABAD 24 HINDU 7659855253 MOINABAD MOINABAD MANDAL GUTTA NARSINGI, GANDIPET NARSINGI, GANDIPET 7 8 KRISHNA `06.10.1985 BC MALE DEGREE RAJENDRANAGAR RANGAREDDY NARSINGI 28 HINDU 8500025824 RAJENDRANAGAR MURALIKRISHNA MANDAL MANDAL KETHAVATH PUTHUGAL VILLAGE, PUTHUGAL VILLAGE, 8 9 PULYA 02.09.1990 ST MALE DEGREE SHABAD RANGAREDDY SHABAD 34 HINDU 8978748060 RAJENDRANAGAR -

Formal Approvals Granted in the Board of Approvals After Coming Into Force of SEZ Rules

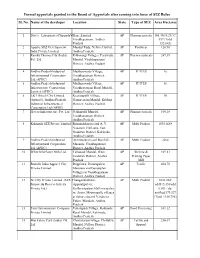

Formal approvals granted in the Board of Approvals after coming into force of SEZ Rules Sl. No. Name of the developer Location State Type of SEZ Area Hectares 1 Divi’s LaboratoriesChippadaVillage,Limited AP Pharmaceuticals 105.496/9.29/17. Visakhapatnam, Andhra 857 (Total Pradesh 132.643) 2 Apache SEZ Development Mandal Tada, Nellore District, AP Footwear 126.90 India Private Limited Andhra Pradesh 3 Ramky Pharma City (India) E-Bonangi Villages, Parawada AP Pharmaceuitacals 247.39 Pvt. Ltd. Mandal, Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 4 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 16 Infrastructural Corporation Visakhapatnam District, Ltd.(APIIC) Andhra Pradesh 5 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 36 Infrastructure Corporation Visakhapatnam Rural Mandal, Limited (APIIC) Andhra Pradesh 6 L&T Hitech City Limited Keesarapalli Village, AP IT/ITES 10 (formerly, Andhra Pradesh Gannavaram Mandal, Krishna Industrial Infrastructural District, Andhra Pradesh Corporation Ltd.(APIIC) 7 Hetero Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. Nakkapalli Mandal, AP Pharmaceuticals 100.28 Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 8 Kakinada SEZ Private Limited Ramanakkapeta and A. V. AP Multi Product 1035.6688 Nagaram Vikllages, East Godavari District, Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh 9 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Atchutapuram and Rambilli AP Multi Product 2264 Infrastructural Corporation Mandals, Visakhapatnam Ltd.(APIIC) District, Andhra Pradesh 10 Whitefield Paper Mills Ltd. Tallapudi Mandal, West AP Writing & 109.81 Godavari District, Andhra Printing -

The Andhra Pradesh Admission and Fee Regulato

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT – The Andhra Pradesh Admission and Fee Regulatory Committee for Professional Courses offered in Private Un-aided Professional Institutions Rules, 2006 – Fixation of Fee structure for MBA / MCA courses in Private Unaided Professional Institutions in the State of Andhra Pradesh for the academic year 2012-13 - Notification – Issued. ================================================ HIGHER EDUCATION (EC.1) DEPARTMENT G.O.Ms.No. 78 Dated:09.10.2012 Read the following:- 1) G.O.Ms.No.90, HE (EC) Dept., Dt.22.12.2003. 2) G.O.MS.No.59, HE (EC.1) Dept., Dt.26.5.2006. 3) G.O.Ms.No.6, H.E. (EC.2) Dept., Dt.8.1.2007. 4) From the Member, Secretary, AFRC, Lr.No.14/AFRC/FF/2012-13/372-374, Dt.27.09.2012. **** O R D E R: The Member Secretary, Admission and Fee Regulatory Committee (AFRC) in the reference 4th read above have submitted the recommendations of AFRC to Government for notification of fee in various Professional Institutions for the year 2012-13. Government, after careful examination of the entire matter, has decided to issue the following notification which shall be published in the Andhra Pradesh extra-ordinary Gazette on 10.10.2012. NOTIFICATION In exercise of the powers conferred under rule 8 and 9 of the Andhra Pradesh Regulation of Admissions into MBA / MCA Professional courses through Common Entrance Test Rules, 2006 issued in the G.O 2nd read above, read with sub rule (v) of Rule 4 of the Andhra Pradesh Admission and Fee Regulatory Committee (For Professional courses offered in Private Un-aided Professional Institutions) Rules, 2006 issued in the G.O 3rd read above and in pursuance of the resolution of the Committee (AFRC) dt.27.09.2010, the Governor of Andhra Pradesh hereby notify the following Fee structure for MBA / MCA courses in Private Unaided Institutions in the State of Andhra Pradesh for the academic year 2012-13:- For MBA / MCA Professional courses: I. -

(Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, for the Year 2010

REPORT U/s 21 (4) OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989, FOR THE YEAR 2010 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. NO. 1 INTRODUCTION 1-3 2 STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM ESTABLISHED FOR 4-8 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. 3 ACTION BY THE POLICE AND THE COURTS IN CASES 9-12 REGISTERED UNDER THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989, DURING 2010. 4. MEASURES TAKEN BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 13-17 5. MEASURES TAKEN BY STATE GOVERNMENTS AND 18-76 UNION TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS STATE GOVERNMENTS 5.1 ANDHRA PRADESH 18-25 5.2 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 26 5.3 ASSAM 27 5.4 BIHAR 28-29 5.5 CHHATTISGARH 30-31 5.6 GOA 32 5.7 GUJARAT 33-35 5.8 HARYANA 36-37 5.9. HIMACHAL PRADESH 38-39 5.10.JHARKHAND 40-41 5.11 KARNATAKA 42-44 5.12 KERALA 45-46 5.13 MADHYA PRADESH 47-49 5.14 MAHARASHTRA 50-52 5.15 MEGHALAYA 53 5.16 ORISSA 54-56 5.17 PUNJAB 57-58 5.18 RAJASTHAN 59-60 5.19 SIKKIM 61 5.20 TAMIL NADU 62-64 5.21 TRIPURA 65 5.22 UTTARAKHAND 66 5.23 UTTAR PRADESH 67-68 5.24 WEST BENGAL 69-70 UNION TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS 5.25 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 71 5.26 CHANDIGARH 72 5.27 DAMAN & DIU 73 5.28 NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI 74 5.29 PUDUCHERRY 75 5.30 OTHER STATE GOVERNMENTS/UNION TERRITORY 76 ADMINISTRATIONS ANNEXURES I EXTRACT OF SECTION 3 OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES 77-79 AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. -

List of Unclaimed Dividend for the Financial Year 2017-18 As on 01-July-2021

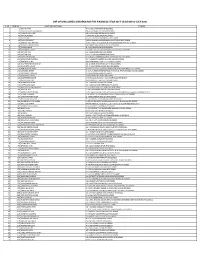

LIST OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2017-18 AS ON 01-JULY-2021 SL NO MEM.NO NAME SRI / SMT / M/S: ADDRESS 1 1 SRI B.N.RATHI 4-5-173,SULTAN BAZAR,HYD,500002 2 30 HUKUMCHAND BHANGADIA 18-4-50,SHAMSHEER GUNJ,HYD,500053 3 31 HARIKISHAN LAHOTI 18-4-50,SHAMSHEER GUNJ,HYD,500053 4 41 NIRMALA SABOO "MANISHA",EDEN BAGH,HYD,500001 5 45 R V PAHADE 3-5-141,EDEN BAGH RAMKOTE,HYD,500001 6 46 KALAVATI DHOOT GOPAL BHAVAN,BASHEER BAGH POLICE COMP,HYD,500029 7 56 NARSING DAS JHAWAR H.NO.12-8-12,IST FLOOR,HUNTER ROAD,RAMANNAPET,WGL,506002 8 63 PRATIBHA MAHESHWARI 402, ROAD NO 5,BANJARA HILLS,HYD,500034 9 73 SHARAYU BAJAJ 4-1-1011,BAGULKUNTA,HYD,500001 10 84 RAJKUMARI SARDA C/o UNITED STEELS,10/11 PAN BAZAR,SEC-BAD,SEC,500003 11 113 GITA BAI SONI 11-3-949,MALLE PALLY,HYD,500001 12 114 MOTILAL SONI NO.11-3-949,MALLAPALLY,HYD,500001 13 118 URMILA BHANDARI 15/7/160/2 LAXMANGIRI,MATH BEGUM BAZAR,HYD,500012 14 120 MANKANVER CHANDAK 10-2-196,EAST MARREDPALLY,SEC-BAD,SEC,500026 15 122 KAMLA DEVI JAJU 1805,MAHANKALI STREET,SEC-BAD,SEC,500003 16 128 BALA PRASAD MUNDHADA 12-11-205/1,WARISGUDA,SEC-BAD,SEC,500061 17 130 SHIVANATH LADHA 12-11-331,WARISGUDA,SEC-BAD,SEC,500061 18 131 NANDKISHORE BUNG PLT.NO.16,RADHE SWAMY COLONY,SIKH ROAD,BOWENPALLY,SEC,500009 19 135 USHADEVI BAHETI 8-2-171 TURNER STREET,BEHIND EMMANUEL PH STUDIO,SEC-BAD,SEC,500003 20 136 CHTRABHUJ CHANDAK 6-1-606,KHAIRATABAD,HYD,500004 21 160 RAM NIVAS SARDA SHAH GUNJ,SHAH GUNJ,HYD,500064 22 163 RAMPERSHAD BANG S/O KHAJULAL BANG,2-4-1081 KACHIGUDA,HYD,500027 23 175 MURLIDHAR LOYA MAIN ROAD,BELLAM -

S.No. H.T.No. CANDIDATE NAME QUALIFICATION ADDRESS 1

TELANGANA STATE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION :: HYDERABAD TEACHER RECRUITMENT TEST IN SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT LANGUAGE PANDIT – (TELUGU)-NOTIFICATION NO.54/2017 RANGAREDDY LOCAL BODY PLAIN S.No. H.T.No. CANDIDATE NAME QUALIFICATION ADDRESS POST BOYALA CHERIVELLA ATMAKUR, DIST, NELLORE, OTHER THAN 1 1754114139 ATMAKUR SUPRIYA M.A TELUGU & TPT TELANGANA STATE 500072 2 1754117465 PAGIDOJU YAKANANDA CHARY M.A TELUGU & TPT 1-92 KANDGATLA ATMAKUR S, SURYAPET, NALGONDA 508222 1-198, THUMUKUNTA VILLAGE AND KUNDURPI MANDAL, 3 1754114266 G NAGESH BABU M.A TELUGU & TPT ANANTHAPURAMU DISTIRCT OTHER THAN TELANGANA STATE - 515766 DAYAKAR REDDY S PL.NO.208, HNO.11-9-88/7 LAXMINAGAR ROAD 4 1754100590 PALVAI SUNITHA B.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU NO.2B, KOTHAPET, RANGAREDDY 500035 VILLAGE POST ANGADIPETA, MANDAL CHANDUR, NALGONDA DIST - 5 1754103836 CHIDANANDAM IDIKUDA M.A TELUGU & TPT 500058 H.NO.2-81/1, BACHUPALLY VILLAGE KANDUKUR MANDAL, RANGAREDDY 6 1754101015 BHUDEVI NARAMONI M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU DISTRICT 501 359 5-36/1, BASVAPUR VILLAGE, POST THURMAMIDI MANDAL BATWARAM, 7 1754111153 S MANJULA M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU RANGAREDDYDIST 501142 1-23/1, BOMREDDYPALLY VILLAGE, BANDIVELKICHERLA, KULKACHERLA 8 1754101020 D NARSIMULU M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU (M), RANGAREDDY DIST - 501 502. 6-35, ALLAPUR POST NAGASAMUNDER, DHARUR, RANGAREDDY DIST 501 9 1754108022 M VENKATESHAM M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU 106 H.NO.1-72/1, BASTEPUR VILLAGE, CHEVELLA MANDAL, RANGAREDDY 10 1754107338 CHAKALI KAVITHA M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU DIST 501 503 H.NO.3-24, VILLAGE ANATHARAM, KULKACHERLA (M) RANGAREDDY DIST 11 1754108773 K BASAIAH M.A TELUGU & TPT 509 335 H.NO.2-211, VENKATESHWARA COLONY, JEELELGUDA, SAROORNAGAR 12 1754108056 MANUPATI LINGAIAH M.A TELUGU & B.ED TELUGU RANGAREDDY DIST 500097 TELANGANA STATE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION :: HYDERABAD TEACHER RECRUITMENT TEST IN SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT LANGUAGE PANDIT – (TELUGU)-NOTIFICATION NO.54/2017 RANGAREDDY LOCAL BODY PLAIN S.No.