The South Australian Prawn Fishery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Working Together Our Achievements 2009 – 2016

Working together Our achievements 2009 – 2016 Photo and logos needed 1 2016© Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources ISBN: 978-1-921595-24-0 This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. All images within this document are credited to Natural Resources Kangaroo Island unless stated otherwise. Front cover image: Travis Bell and Grant Flanagan inspecting crop health as part of the AgKI Potential Project. Work outline in this document is funded by: 2 2 Message from the Presiding Member 4 Message from the Regional Director 5 Socio-economic Snapshot 6 Culture & Heritage Snapshot 8 Flora Snapshot 10 Fauna Snapshot 14 Marine & Coastal Snapshot 18 Freshwater Snapshot 22 Land Condition Snapshot 26 Biosecurity & Pests Snapshot 30 Climate Change Snapshot 34 Community Engagement & Capacity Building Snapshot 38 A New NRM Plan for KI 42 3 3 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING MEMBER The inaugural Kangaroo Island Natural Resources 2009, fencing off native vegetation, installing creek crossings Management (NRM) Plan 2009–2019 was prepared when and liming acid soils. Kangaroo Island was declared one of eight South Australian However, some systems are out of balance, particularly where NRM regions under the Natural Resources Management Act human activities have tipped the scales, and many plant 2004, and while Kangaroo Island may be the smallest region and animal species continue to decline in numbers on the geographically, it is certainly one of the most precious! island, including top order predators such as the Rosenberg’s The Kangaroo Island community is deeply connected to goanna and osprey. -

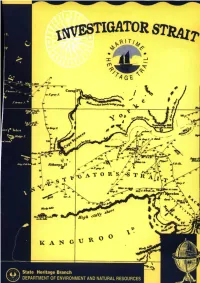

Lsvbstigator Stratr

p lSVBSTIGATOR STRAtr Wtdftt l. rJ r—A* State Heritage Branch S DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Slate Heritage Branch Department of Environment and Natural Resources Text by Terry Arnott Design and illustrations by Design Publishing Unit Adelaide, 1996 ISBN 0 7308 4720 9 F1S 14983 0VBSTIGATOR STKajj, '/Tv • v CONTENTS page Introduction 1 Map showing Investigator Strait Shipwrecks 8 Table of Investigator Strait Shipwrecks 9 S.S .Clan Ranald 10 Ethel 14 S.S .Ferret 16 Hougomont 18 S.S. Marion 21 S.S. Pareora 24 S.S. Willy a ma 27 Yatala Reef 30 Althorpe Island Shipwrecks 32 References 34 Diver Services 35 NOTES 36 The steering quadrant is visible above water as a diver examines the Willyama's sternpost. INVESTIGATOR strait INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Investigator Strait Maritime Heritage Trail. An historical background nvestigator Strait is the extensive and navigable stretch of water which I lies between southern YorkejEeninsula"ancfeKangaroo Island. Captain Matthew Flinders gave it this-name'on. in honour of his ship, HMS Investigator. jm " \ South Australia has over 3OOOokilo'rrie fres of coastline, deeply indented by mwA! lij.i| two gulfs, Gulf St. Vincent andfeSpencer-sGulffaiiwhichSare Winked at their southern approacheh s bh y thtvSe waters'of Investigator Strait. From the middlHH.e of last century Investigator Strait\nas,played an important part'in the trade and Vl^x , — \/ communications network of\SouthvAustralia as a^natural route for shipping. j^ II The first ships to use the strait\oir?a$r,egular basis were engaged in early f _ A whaling and sealing ventures. -

S P E N C E R G U L F S T G U L F V I N C E N T Adelaide

Yatala Harbour Paratoo Hill Turkey 1640 Sunset Hill Pekina Hill Mt Grainger Nackara Hill 1296 Katunga Booleroo "Avonlea" 2297 Depot Hill Creek 2133 Wilcherry Hill 975 Roopena 1844 Grampus Hill Anabama East Hut 1001 Dawson 1182 660 Mt Remarkable SOUTH Mount 2169 440 660 (salt) Mt Robert Grainger Scobie Hill "Mazar" vermin 3160 2264 "Manunda" Wirrigenda Hill Weednanna Hill Mt Whyalla Melrose Black Rock Goldfield 827 "Buckleboo" 893 729 Mambray Creek 2133 "Wyoming" salt (2658±) RANGE Pekina Wheal Bassett Mine 1001 765 Station Hill Creek Manunda 1073 proof 1477 Cooyerdoo Hill Maurice Hill 2566 Morowie Hill Nackara (abandoned) "Bulyninnie" "Oak Park" "Kimberley" "Wilcherry" LAKE "Budgeree" fence GILLES Booleroo Oratan Rock 417 Yeltanna Hill Centre Oodla "Hill Grange" Plain 1431 "Gilles Downs" Wirra Hillgrange 1073 B pipeline "Wattle Grove" O Tcharkuldu Hill T Fullerville "Tiverton 942 E HWY Outstation" N Backy Pt "Old Manunda" 276 E pumping station L substation Tregalana Baroota Yatina L Fitzgerald Bay A Middleback Murray Town 2097 water Ucolta "Pitcairn" E Buckleboo 1306 G 315 water AN Wild Dog Hill salt Tarcowie R Iron Peak "Terrananya" Cunyarie Moseley Nobs "Middleback" 1900 works (1900±) 1234 "Lilydale" H False Bay substation Yaninee I Stoney Hill O L PETERBOROUGH "Blue Hills" LC L HWY Point Lowly PEKINA A 378 S Iron Prince Mine Black Pt Lancelot RANGE (2294±) 1228 PU 499 Corrobinnie Hill 965 Iron Baron "Oakvale" Wudinna Hill 689 Cortlinye "Kimboo" Iron Baron Waite Hill "Loch Lilly" 857 "Pualco" pipeline Mt Nadjuri 499 Pinbong 1244 Iron -

Australia: Reconstructing Estimates of Total Fisheries Removal, 1950-2010

Fisheries Centre The University of British Columbia Working Paper Series Working Paper #2015 - 02 Australia: Reconstructing estimates of total fisheries removal, 1950-2010 Kristin Kleisner, Ciara Brennan, Anna Garland, Stephanie Lingard, Sean Tracey, Phil Sahlqvist, Angelo Tsolos, Daniel Pauly, and Dirk Zeller Year: 2015 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] This working paper is made available by the Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada. Australia - Kleisner et al. 1 AUSTRALIA: RECONSTRUCTING ESTIMATES OF TOTAL FISHERIES REMOVALS 1950-2010 Kristin Kleisnera, Ciara Brennana, Anna Garlandb, Stephanie Lingarda, Sean Traceyc, Phil Sahlqvistd, Angelo Tsolose, Daniel Paulya, and Dirk Zellera a Sea Around Us, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, Canada b Fisheries Queensland, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, GPO Box 46, Brisbane, Qld 4001, Australia c Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Private bag 49, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia d Fisheries and Risk Analysis Branch, ABARES, GPO Box 1563, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia e SARDI SA Aquatic Sciences Centre, Fisheries – Information Services, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, SA 5022 Australia [email protected]; kristen.kleisner @noaa.gov; c [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] ABSTRACT Australia’s commercial fisheries are of significant value to the Australian economy, with the twenty Commonwealth fisheries alone worth around AUD$320 million in production value. -

HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406 Hydrographic Department Ministry of Defence Taunton, Somerset TA1 2DN National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Copied: 1987 1 HISTORICAL NOTE The Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty was created by an Order-in-Council of 12 August 1795 which stated that it would be responsible for ‘the care of such charts, as are now in the office, or may hereafter be deposited’ and for ‘collecting and compiling all information requisite for improving Navigation, for the guidance of the commanders of His Majesty’s ships’. Alexander Dalrymple, who had been Hydrographer to the East India Company since 1799, was appointed the first Hydrographer. In 1797 the Hydrographer’s staff comprised an assistant, a draughtsman, three engravers and a printer. It remained a small office for much of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, under Captain Thomas Hurd, who succeeded Dalrymple as Hydrographer in 1808, a regular series of marine charts were produced and in 1814 the first surveying vessels were commissioned. The first Catalogue of Admiralty Charts appeared in 1825. In 1817 the Australian-born navigator Phillip Parker King was supplied with instruments by the Hydrographic Department which he used on his surveying voyages on the Mermaid and the Bathurst. Archives of the Hydrographic Department The Australian Joint Copying Project microfilmed a considerable quantity of the written records of the Hydrographic Department. They include letters, reports, sailing directions, remark books, extracts from logs, minute books and survey data books, mostly dating from 1779 to 1918. They can be found on reels M2318-37 and M2436-67. -

A Precious Asset

Gulf St Vincent A PRECIOUS ASSET Gulf St Vincent A PRECIOUS AssET Introduction It is more than 70 years since Since that time, the Gulf has We need these people, and other William Light sailed up the eastern provided safe, reliable transport for members of the Gulf community, side of Gulf St Vincent, looking for most of our produce and material to share their knowledge, to the entrance to a harbour which needs, as well as fresh fish, coastal make all users of the Gulf aware had been reported by the explorer, living, recreation and inspiration. of its value, its benefits and its Captain Collet Barker, and the In return we have muddied its vulnerability. It is time for us all to whaling captain, John Jones. waters with stormwater, effluent learn more about Gulf St Vincent, He found waters calm and clear and industrial wastes, bulldozed to recognise the priceless asset enough to avoid shoals and to its dunes, locked up sand under we have, and to do our utmost to safely anchor through the spring houses and greedily exploited its reverse the trail of destruction we gales blowing from the south-west. marine life. Just reflect a moment have left in the last 00 years. Perhaps even he saw sea eagles on what Adelaide in particular, and The more we know of the Gulf, fishing or nesting in the low trees South Australia as a whole, would its physical nature and marine life, and bushes on the dunes, which be like without Gulf St Vincent, to the more readily we recognise extended along the coast from realise the importance of the Gulf the threats posed by increasing Brighton to the Port River. -

Technical Report No 8 – Physical Oceanographic Studies of Adelaide Coastal Waters Using High Resolution Modeling, In

Stage 2 Research Program 2003 - 2005 Technical Report No. 8 July 2005 Physical oceanographic studies of Adelaide coastal waters using high resolution modeling, in-situ observations and satellite techniques Sub Task 4 - Draft Final Technical Report Physical oceanographic studies of Adelaide coastal waters using high resolution modeling, in-situ observations and satellite techniques Sub Task 4 - Draft Final Technical Report Authors Charitha Pattiaratchi and Rhys Jones Centre for Water Research University of Western Australia Nedlands, Western Australia, 6907 Copyright © 2005 South Australian Environment Protection Authority This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Environment Protection Authority. Disclaimer This report has been prepared by consultants for the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the EPA. The EPA cannot guarantee the accuracy of the report, and does not accept liability for any loss or damage incurred as a result of relying on its accuracy. ISBN ISBN 1 876562 97 8 July 2005 Reference This report can be cited as: Pattiaratchi C. and R. Jones (2005). “Physical and oceanographic studies of Adelaide coastal waters using high resolution modeling, in-situ observations and satellite techniques – PPM 2 Sub Task 4 Draft Final Technical Report”. ACWS Technical Report No. 8 prepared for the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study Steering Committee. Centre for Water Research, University of Western Australia, Nedlands WA 6907. -

Parks of Kangaroo Island Escape to the Wild Welcome to Kangaroo Island’S Parks

Parks of Kangaroo Island Escape to the wild Welcome to Kangaroo Island’s parks The Department of Environment, Water Kangaroo Island is ‘a big island’ and Natural Resources manages one – the third largest off the coast of national park, eighteen conservation Australia. Many visitors frequently parks, four marine parks and five state ‘We wish we could have stayed wilderness protection areas on longer. We didn’t realise the Island Kangaroo Island. Some areas are vast, was so large!’. Don’t be disappointed. others small – all possessing the natural Ensure you allow adequate time to beauty unique to Kangaroo Island. The best appreciate all that is on offer parks conserve an array within the parks. of natural environments. Mallee Please consider the possible weather woodlands, low open forests and conditions at the site you are planning woodlands, karst landscape, fresh and to visit. For example, when leaving saline lakes, spectacular coastal cliffs your accomodation it may be mild but and sand dune systems all provide the conditions could be very different habitat to an abundant range of wildlife. once you reach the south coast. There are a wide variety of things to It is recommended that you always see and do on Kangaroo Island. This take a drinking water, a jacket and booklet provides information about the a sun hat. experiences available within the parks. Contents Welcome to Kangaroo Island’s parks 6 Cape du Couedic 20 Getting about 6 About heritage accommodation 21 Your safety 6 Special offer 22 Where to go, what to do 7 What visitors say 23 Fires 7 Bushwalking 24 Baudin Conservation Park 8 Walks and hikes 24 Beyeria Conservation Park 8 Walk Safely 24 Cape Bouguer Wilderness Coastal Treks 25 Protection Area 8 Kangaroo Island Wilderness Trail 25 Cape Gantheaume Conservation Park 8 Kangaroo Island map 26 Cape Gantheaume Select your trail 28 Wilderness Protection Area 9 Cape Willoughby Conservation Park 10 Trail descriptions 30 Flinders Chase National Park 12 1. -

Annotated Supplement to the Commander's Handbook On

ANNOTATED SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMMANDER’S HANDBOOK ON THE LAW OF NAVAL OPERATIONS NEWPORT, RI 1997 15 NOV 1997 INTRODUCTORY NOTE The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations (NWP 1-14M/MCWP S-2.1/ COMDTPUB P5800.1), formerly NWP 9 (Rev. A)/FMFM l-10, was promulgated to U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Coast Guard activities in October 1995. The Com- mander’s Handbook contains no reference to sources of authority for statements of relevant law. This approach was deliberately taken for ease of reading by its intended audience-the operational commander and his staff. This Annotated Supplement to the Handbook has been prepared by the Oceans Law and Policy Department, Center for Naval Warfare Studies, Naval War College to support the academic and research programs within the College. Although prepared with the assistance of cognizant offices of the General Counsel of the Department of Defense, the Judge Advocate General of the Navy, The Judge Advocate General of the Army, The Judge Advocate General of the Air Force, the Staff Judge Advo- cate to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, the Chief Counsel of the Coast Guard, the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Unified Combatant Commands, the annotations in this Annotated Supplement are not to be construed as representing official policy or positions of the Department of the Navy or the U.S. Governrnent. The text of the Commander’s Handbook is set forth verbatim. Annotations appear as footnotes numbered consecutively within each Chapter. Supplementary Annexes, Figures and Tables are prefixed by the letter “A” and incorporated into each Chapter. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 03:55:34PM Via Free Access 438 Appendix

Appendix Lists of Alleged Historic Bays1 It will be noted that such ‘listings’ by post-war commentators vary quite considerably, several including bays which others omit. This in itself points up the selectivity of such supposed ‘historic’ examples of maritime claims. Scovazzi et al., for example, point out in their Foreword2 that decisions of the US Supreme Court were omitted in that work “since these decisions are probably not relevant for the external relations of the [US]”. Also the UN Juridical Regime omits giving a list,3 stating that even a centralised international registration system of historic claims (as has been mooted in the past) might prove to be impracticable. It may be noted again that the Alexander Archipelago off SE Alaska does not feature as an example of historic waters in any of these listings. A sample of post-war listings of historic maritime claims include: Argentina River Plate Estuary (UN Memorandum);4 Australia (see generally Strohl)5 Anxious, Encounter, Lacepede and Riovoli (Scovazzi,6 Nixon);7 Van Dieman Gulf (also Nixon), Buckingham Bay, Blue Mud Bay, Coffin Bay, Streaky Bay, Spencer Gulf, Investigator Strait/St Vincent’s Gulf, Exmouth Gulf (also Nixon), Roebuck Bay, Shark Bay (also Nixon); Broad Sound, Upstart Bay, Moreton Bay, Hervey Bay, Oyster Bay, Storm Bay (UN Memorandum). 1 See, e.g., A.M. Lewis in J.A. Roach, Navigational Restrictions Within the New Law of the Sea Context: Geographical Implications for the US, Nijhoff (2016) at p. 39, where historic claims are placed into three categories: namely, lists of bays “for which historic claims have been clearly made”, of bays “for which claims seem somewhat uncertain”; and of bays “for which claims might be made”. -

Reef Fishes of Conservation Concern in South Australia

Reef Fishes of Conservation Concern in South Australia A Field Guide In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught. — Baba Dioum, 1968. by Janine L. Baker, Marine Ecologist SUPPORTED BY THE Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board Acknowledgments Thanks to the Adelaide and Mt Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management (AMLR NRM) Board for supporting the development of this field guide. Particular thanks to Janet Pedler and Liz Millington at AMLR NRM Board for guidance, advice and support. I am grateful to DENR, especially Patricia von Baumgarten and Simon Bryars, for part- supporting my time in writing an e-book on South Australian fishes, from which much of the information in this field guide was derived. Thanks to all of the marine researchers and divers who generously provided images for this guide. In alphabetical order, they include: James Brook, Adrian Brown, Simon Bryars, Helen Crawford, Graham Edgar, Chris Hall, Barry Hutchins, Rudie Kuiter, Paul Macdonald, Phil Mercurio, David Muirhead, Kevin Smith and Rick Stuart-Smith. The keen eye and skill of these photographers have significantly contributed to the visual appeal and educational value of the work. A photograph from the internet has also been included, and thanks to the photographer Richard Ling for making his image of Girella tricuspidata available in the public domain. I am grateful to Graham Edgar, Scoresby Shepherd and Simon Bryars for taking the time to edit and proofread the draft text. Thanks to Céline Lawrence for formatting the draft booklet for web-based printing and hard copy printing.