November 2018 ACBL Bulletin Notes Jeff Kroll Sam Khayatt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things You Might Like to Know About Duplicate Bridge

♠♥♦♣ THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT DUPLICATE BRIDGE Prepared by MayHem Published by the UNIT 241 Board of Directors ♠♥♦♣ Welcome to Duplicate Bridge and the ACBL This booklet has been designed to serve as a reference tool for miscellaneous information about duplicate bridge and its governing organization, the ACBL. It is intended for the newer or less than seasoned duplicate bridge players. Most of these things that follow, while not perfectly obvious to new players, are old hat to experienced tournaments players. Table of Contents Part 1. Expected In-behavior (or things you need to know).........................3 Part 2. Alerts and Announcements (learn to live with them....we have!)................................................4 Part 3. Types of Regular Events a. Stratified Games (Pairs and Teams)..............................................12 b. IMP Pairs (Pairs)...........................................................................13 c. Bracketed KO’s (Teams)...............................................................15 d. Swiss Teams and BAM Teams (Teams).......................................16 e. Continuous Pairs (Side Games)......................................................17 f. Strategy: IMPs vs Matchpoints......................................................18 Part 4. Special ACBL-Wide Events (they cost more!)................................20 Part 5. Glossary of Terms (from the ACBL website)..................................25 Part 6. FAQ (with answers hopefully).........................................................40 Copyright © 2004 MayHem 2 Part 1. Expected In-Behavior Just as all kinds of competitive-type endeavors have their expected in- behavior, so does duplicate bridge. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a competitive adventure.....as opposed to the social outing that you may be used to at your rubber bridge games. Now that is not to say that you can=t be sociable at the duplicate table. Of course you can.....and should.....just don=t carry it to extreme by talking during the auction or play. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 178 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 October 2017 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with hands when, if you choose to pass, the auction will end. You are West in BRIDGEthe auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer North. Love All. 4. Dealer West. Love All. 7. Dealer North. Love All. 10. Dealer East. E/W Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 3 ♠ A J 10 6 5 ♠ 4 2 ♥ A K 8 7 N ♥ A 8 7 6 N ♥ 10 9 8 4 3 N ♥ K Q 3 N W E W E W E W E ♦ J 9 8 6 5 ♦ A J 2 ♦ Void ♦ 7 6 5 S S S S ♣ Q J 3 ♣ Q J 6 ♣ A 7 4 ♣ K Q J 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♥ 1♠ Pass Pass 1♣ 2♦1 Pass 1♥ 1♠ ? ? Pass Dbl Pass Pass 2♣ 2♠ 3♥ 3♠ ? 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass 1Weak jump overcall ? 2. Dealer North. Love All. 5. Dealer West. Love All. 8. Dealer East. Love All. 11. Dealer North. N/S Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 7 6 5 ♠ A 7 6 5 4 3 ♠ 4 3 2 ♥ A J N ♥ 4 N ♥ A K 3 N ♥ A 7 6 N W E W E W E W E ♦ 8 7 2 ♦ A K 3 ♦ 2 ♦ A 8 7 6 4 S S S S ♣ K Q J 10 5 4 3 ♣ J 10 8 2 ♣ A 5 2 ♣ 7 6 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♠ 2♥ Pass Pass 3♦ Pass 1♣ 3♥ Dbl ? ? Pass 3♥ Pass Pass 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass ? ? 3. -

Bridge Glossary

Bridge Glossary Above the line In rubber bridge points recorded above a horizontal line on the score-pad. These are extra points, beyond those for tricks bid and made, awarded for holding honour cards in trumps, bonuses for scoring game or slam, for winning a rubber, for overtricks on the declaring side and for under-tricks on the defending side, and for fulfilling doubled or redoubled contracts. ACOL/Acol A bidding system commonly played in the UK. Active An approach to defending a hand that emphasizes quickly setting up winners and taking tricks. See Passive Advance cue bid The cue bid of a first round control that occurs before a partnership has agreed on a suit. Advance sacrifice A sacrifice bid made before the opponents have had an opportunity to determine their optimum contract. For example: 1♦ - 1♠ - Dbl - 5♠. Adverse When you are vulnerable and opponents non-vulnerable. Also called "unfavourable vulnerability vulnerability." Agreement An understanding between partners as to the meaning of a particular bid or defensive play. Alert A method of informing the opponents that partner's bid carries a meaning that they might not expect; alerts are regulated by sponsoring organizations such as EBU, and by individual clubs or organisers of events. Any method of alerting may be authorised including saying "Alert", displaying an Alert card from a bidding box or 'knocking' on the table. Announcement An explanatory statement made by the partner of the player who has just made a bid that is based on a partnership understanding. The purpose of an announcement is similar to that of an Alert. -

Beat Them at the One Level Eastbourne Epic

National Poetry Day Tablet scoring - the rhyme and reason Rosen - beat them at the one level Byrne - Ode to two- suited overcalls Gold - time to jump shift? Eastbourne Epic – winners and pictures English Bridge INSIDE GUIDE © All rights reserved From the Chairman 5 n ENGLISH BRIDGE Major Jump Shifts – David Gold 6 is published every two months by the n Heather’s Hints – Heather Dhondy 8 ENGLISH BRIDGE UNION n Bridge Fiction – David Bird 10 n Broadfields, Bicester Road, Double, Bid or Pass? – Andrew Robson 12 Aylesbury HP19 8AZ n Prize Leads Quiz – Mould’s questions 14 n ( 01296 317200 Fax: 01296 317220 Add one thing – Neil Rosen N 16 [email protected] EW n Web site: www.ebu.co.uk Basic Card Play – Paul Bowyer 18 n ________________ Two-suit overcalls – Michael Byrne 20 n World Bridge Games – David Burn 22 Editor: Lou Hobhouse n Raggett House, Bowdens, Somerset, TA10 0DD Ask Frances – Frances Hinden 24 n Beat Today’s Experts – Bird’s questions 25 ( 07884 946870 n [email protected] Sleuth’s Quiz – Ron Klinger’s questions 27 n ________________ Bridge with a Twist – Simon Cochemé 28 n Editorial Board Pairs vs Teams – Simon Cope 30 n Jeremy Dhondy (Chairman), Bridge Ha Ha & Caption Competition 32 n Barry Capal, Lou Hobhouse, Peter Stockdale Poetry special – Various 34 n ________________ Electronic scoring review – Barry Morrison 36 n Advertising Manager Eastbourne results and pictures 38 n Chris Danby at Danby Advertising EBU News, Eastbourne & Calendar 40 n Fir Trees, Hall Road, Hainford, Ask Gordon – Gordon Rainsford 42 n Norwich NR10 3LX -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 172 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 April 2017 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with responding to an opening one-level bid. You are West in the auctions BRIDGEbelow, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer East. Love All. 4. Dealer East. Love All. 7. Dealer East. Love All. 10. Dealer East. N/S Game. ♠ K 6 3 ♠ A K Q J 10 4 ♠ A K 7 6 ♠ K Q 7 5 4 ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ Q 4 2 N 8 N 5 N A 4 3 N ♦ 8 7 6 W E ♦ K 9 4 W E ♦ 6 3 W E ♦ K 6 4 2 W E ♣ K Q 8 6 S ♣ 6 5 3 S ♣ A Q 8 6 5 4 S ♣ 2 S West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♣ Pass 1♦ Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass ? ? ? ? 2. Dealer East. Love All. 5. Dealer East. Love All. 8. Dealer East. Love All. 11. Dealer East. N/S Game. ♠ 9 8 7 6 5 ♠ A 8 7 ♠ 8 4 ♠ 7 6 ♥ K 4 3 N ♥ 8 2 N ♥ K 9 4 N ♥ Q J 2 N W E W E W E W E ♦ J 8 3 2 ♦ A Q 8 4 2 ♦ A 7 6 5 2 ♦ 7 S S S S ♣ 4 ♣ K 3 2 ♣ 8 4 3 ♣ A 8 7 6 5 4 3 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♣ Pass 1♦ Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass ? ? ? ? 3. -

Friendly Bridge Book, January 2020 Edition

Beginning Bridge Lessons By Ed Kinlaw and Linda MacCleave Richmond Bridge Association Richmond, Virginia Copyright © 2003 First printing September 2003 Revised second printing February 2004 Revised third printing May 2004 Revised fourth printing September 2004 Revised fifth printing February 2005 Revised sixth printing September 2005 Revised seventh printing February 2006 Revised eighth printing August 2006 Revised ninth printing March 2007 Tenth printing September 2007 Revised eleventh printing January 2008 Revised twelfth printing August 2008 Revised thirteenth printing February 2009 Fourteenth printing July 2009 Revised fifteenth printing February 2010 Sixteenth printing August 2010 Revised seventeenth printing January 2011 Revised eighteenth printing August 2011 Revised nineteenth printing March 2012 Revised twentieth printing April 2012 Twenty-first printing August 2012 Revised Twenty-fifth printing January 2014 Revised 26th printing August 2014 Revised 27th printing February 2015 28th printing August 2015 29th printing February 2016 30th printing July 2016 31st printing January 2017 32nd printing September 2017 33rd printing February 2018 34th printing August 2018 35th printing February 2019 36th printing August 2019 37th revised printing February 2020 2 Table of Contents Lesson 1: Mechanics of a Hand in Duplicate Bridge 5 Lesson 2: How to Open and How to Respond to One-level Suit 12 Lesson 3: Rebids by Opening Bidder and Responder 17 Lesson 4: Overcalls 24 Lesson 5: Takeout Doubles 27 Lesson 6: Responding to No-Trump Opening—Stayman -

NSBC News Item

NSBC News Item Mar 2020 No.1 Editor: Kevin Davies Visit an online Inside This Issue: Pages bridge club (BBO) Visit online bridge club 1 for the first time BB0 2 BBO Logon 3 Kevin Davies, Editor BBO Watch Anonymously 4-5 Document Aim BBO Registration 6 The aim of this document is to enable NSBC BBO Live 7-10 bridge players, especially those who have not BBO Auto Tools 11-16 used an online bridge club service before, to gain the confidence to play online, thus enabling them to continue to enjoy playing our great BBO is regularly used for viewing Australian game of bridge at this difficult time. Our focus is Championship and other World matches, on Bridge Base Online (BBO) although these are not occurring at present with the virus problems. It is expected that NSBC will establish some regular club bridge sessions on BBO that you can join over the next few weeks. How to access BBO via a web There are a number of online Bridge Clubs you browser: can use to play bridge from home: Some examples include: Click Here Web browser Access: Bridge Base Online (BBO) US OK Bridge US Or type into your browser this address Step Bridge Australia AUS Bridge Club Live UK https://www.bridgebase.com/index.php I am a regular user of BBO (Bridge Base Or for just fast access to the Log in Pane Online), which is the most comprehensive site. User access to BBO is supported via a https://www.bridgebase.com/v3/ number of access channels. -

Appendix G Special Conditions to the Use of Bidding Boxes and Screens These Conditions of Contest (Coc) May Not Be Changed During the Course of an Event

Appendix G Special Conditions to the use of Bidding Boxes and Screens These Conditions of Contest (CoC) may not be changed during the course of an event. Lack of knowledge does not constitute cause for exemption. BIDDING BOXES (no screens) 1. Players must choose a call before touching any card in the bidding box. A call is considered made when a bidding card is removed from the bidding box and held touching, or nearly touching, the table — or maintained in such a position to indicate that the call has been made. 2. A call may be changed without penalty, under the provisions of Law 25A, only if a player has inadvertently taken out the wrong bidding card and the player corrects or attempts to correct his mistake without pause for thought and the player’s partner has not made a call. SCREEN PROCEDURES At tables with a VuGraph operator present, players and kibitzers shall surrender all electronic communications devices to the VuGraph operator before beginning play. These devices will be returned upon completion of all the boards in the segment. The purpose of the screen is to prevent information from being transmitted from one side to the other. Players should strongly endeavor in all situations to ensure that sounds of any kind are not heard on the opposite side of the screen during the auction. The screen is placed diagonally across the table in such fashion that North and East, South and West are screenmates (unless otherwise required as a reasonable accommodation to a disabled player). The board is placed in the middle of a moveable tray. -

General Conditions of Contest for The

WORLD BRIDGE FEDERATION GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CONTEST For all World Championships and other Tournaments held under the auspices of the World Bridge Federation ©WBF May 2011 Issued by the World Bridge Federation Via della Moscova 46/5, Milan 20121, Italy Contents 1. World Mind Sport Games (WMSG) ................................................................................... 6 2. Definitions for the General Conditions Of Contest ........................................................... 6 2.1 Appeals Form ............................................................................................................ 6 2.2 Approved Recorder ................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Brown Sticker Announcement Form ......................................................................... 7 2.4 Chief Tournament Director and Assistant Chief Tournament Director .................... 7 2.5 Convention Card Desk .............................................................................................. 7 2.6 Director or Tournament Director ............................................................................. 7 2.7 Eligible Zone ............................................................................................................. 7 2.8 Executive Council ...................................................................................................... 7 2.9 Guide to Completion................................................................................................ -

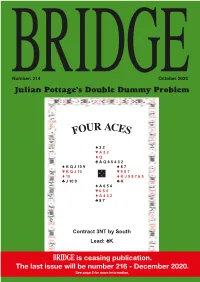

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

Tips for the Club Director Tables Will Be Playing

Harry Falk's web site is IF YOU RUN A SECTIONAL! harrybridge.com it contains All changes to sanctioned sectionals information about the local require approval from the District 9 duplicates in his area as well Tournament Committee as well as our as tournaments at which he District Coordinator, Patty Johnson. officiates. If you change anything, whether it be your dates or the type of sectional Tips for the Club Director tables will be playing. (An easy way to or the location, or if you decide by Harry Falk • [email protected] do this is to look at your club report to cancel an already-sanctioned For those of you who don't know, I am not only a tournament director, but for the same day in the previous year. tournament, please let Patty Johnson also a club director and manager. I've been directing club games for 17 years, Tournament directors use previous know immediately by emailing her years' figures as guidelines for at [email protected]. and, by now, I'd estimate that I've run at least 2,500 sessions of club bridge in Information should also be sent to that time. I'd like to take this chance to offer a few suggestions to club managers estimated turnout, and the prior year is a remarkably good predictor of what Shirley Seals, Chair of the Tournament and directors to help make their games run more smoothly, and perhaps a few to Committee, at [email protected]. make the game a more enjoyable experience for players. will happen this year). -

Lord, Popkin Take Silver Ribbon

March 6-March 16, 2003 46th Spring North American Bridge Championships Daily Bulletin Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Volume 46, Number 5 Tuesday, March 11, 2003 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Lord, Popkin take Silver Ribbon Roger Lord and Alan Popkin, the leaders at the halfway point, never let up and emerged as winners of the Levintritt Silver Ribbon Pairs. Although their lead was beginning to shrink as the second final session wound down, the St. Louis residents were in first from start to finish. They scored 1636.64 (51 top) to 1620.71 for the runners- up – John Russell of North Barrington IL and Bernace DeYoung of Miami FL. Third place went to Arnie Fisher of Clementon NJ and Fred Paul of Fort Lee NJ. Popkin is an attorney in St. Louis. Lord is a bridge teacher. In the glow of victory, they were unstinting in Judy Kay presents a trophy to John Marks praise of each other. commemorating his work in the Philadelphia area over the past four decades. Continued on page 7 Roger Lord and Alan Popkin Goodwill honors Bridge Pro Tour John Marks gains momentum This tournament is going strong – good space, The beginning was modest – four events with good entertainment, good attendance, good spirits. total prize money of $42,000. Next year, says Larry John Marks, tournament chairman, was honored by King, the Bridge Pro Tour will feature 22 events at the Goodwill Committee yesterday as the inspira- regionals and NABCs with a total cash payout of tion behind the effort. Judy Kay presented him with nearly $300,000.