Report to the Government of Montenegro on the Visit To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analysis of Parafiscal Burdens at Local Level

Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva - Summary - Note This document is a summary, i.e. a brief overview of a part of the content of the original publication published by Montenegrin Employers Federation (MEF) in Mon- tenegrin language as a “Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro: The Analysis of Parafiscal Burdens at -Lo cal level - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva”. Original version of the publication is available at MEF website www.poslodavci.org Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva - SUMMARY Podgorica, November 2018 Title: Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro:THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva Authors: dr Vasilije Kostić Montenegrin Employers’ Federation Publisher: Montenegrin Employers Federation (MEF) Cetinjski put 36 81 000 Podgorica, Crna Gora T: +382 20 209 250 F: +382 20 209 251 E: [email protected] W: www.poslodavci.org For publisher: Suzana Radulović Place and date: Podgorica, December 2018 This publication has been published with the support of the (Bureau for Employers` Activities of the) International Labour Organization. The responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. The International Labour -Or ganisation (ILO) takes no responsibility for the correctness, accuracy or reliability of any of the materials, information or opinions expressed in this report. Executive Summary It is common knowledge that productivity determines the limits of development of the standard of living of any country, and modern globalized economy emphasizes the importance of productivity to the utmost limits. -

Socio Economic Analysis of Northern Montenegrin Region

SOCIO ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE NORTHERN REGION OF MONTENEGRO Podgorica, June 2008. FOUNDATION F OR THE DEVELOPMENT O F NORTHERN MONTENEGRO (FORS) SOCIO -ECONOMIC ANLY S I S O F NORTHERN MONTENEGRO EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR : Veselin Šturanović STUDY REVIEWER S : Emil Kočan, Nebojsa Babovic, FORS Montenegro; Zoran Radic, CHF Montenegro IN S TITUTE F OR STRATEGIC STUDIE S AND PROGNO S E S ISSP’S AUTHOR S TEAM : mr Jadranka Kaluđerović mr Ana Krsmanović mr Gordana Radojević mr Ivana Vojinović Milica Daković Ivan Jovetic Milika Mirković Vojin Golubović Mirza Mulešković Marija Orlandić All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means wit- hout the prior written permission of FORS Montenegro. Published with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the CHF International, Community Revitalization through Democratic Action – Economy (CRDA-E) program. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for Interna- tional Development. For more information please contact FORS Montenegro by email at [email protected] or: FORS Montenegro, Berane FORS Montenegro, Podgorica Dušana Vujoševića Vaka Đurovića 84 84300, Berane, Montenegro 81000, Podgorica, Montenegro +382 51 235 977 +382 20 310 030 SOCIO ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE NORTHERN REGION OF MONTENEGRO CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS: ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Important Business Zones - Potentials

DANILOVGRAD IN NUMBERS • Surface area: 501 km² • Population: 18.472 (2011 census) – increased for 12% since 2003 census • Elevation from 30 to 2100 MASL • Valleys - up to 200 MASL – 140,5 km² • Hills - up to 600 MASL– 81 km² • Mountains above 650 MASL – 275 km² • Highest peaks – Garač (Peak Bobija) 1436 MASL, Ponikvica (Peak Kula) 1927 MASL and Maganik (Petrov Peak) 2127 MASL COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGES • Strategic geographic location • Transport connections • Defined industrial (business) zones • Development resources • Efficient local administration • Incentive measures and subventiones STRATEGIC GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION TRANSPORT CONNECTIONS • 18 km from capital city Podgorica • 25 km from International Airport (Golubovci) • 70 km from International Seaport (Bar) • 20 km from highway Bar – Boljare which is in construction • 10 km from future Adriatic – Ionian highway (Italy – Slovenia – Croatia – Bosnia and Hercegovina – Albania – Greece) • Rail transport DEFINED INDUSTRIAL (BUSINESS) ZONES • 2007 year - Spatial Plan was adopted with defined industrial (business) zones • 2014 year – Spatial – urban Plan was adopted with defined additional industrial (business) zones • The biggest zones are along the major roads: European route E762 Sarajevo – Podgorica – Tirana (12 km) – 100 m from both sides Regional road Bogetići – Danilovgrad – Spuž – Podgorica (11 km) – 100 m from both sides IMPORTANT BUSINESS ZONES - POTENTIALS DANILOVGRAD – ŽDREBAONIK MONASTERY • Built infrastructure • Religious tourism and accommodation capacities (Ždrebaonik Monastery) -

BR IFIC N° 2550 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2550 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha: 09.08.2005 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de la Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-additioner MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 105112284 F 0.0838 S ANDRE DE COR F 4E55'0" 45N55'0" FX 1 SUP 2 105112298 -

USAID Economic Growth Project

USAID Economic Growth Project BACKGROUND The USAID Economic Growth Project is a 33-month initiative designed to increase economic opportunity in northern Montenegro. Through activities in 13 northern municipalities, the Economic Growth Project is promoting private-sector development to strengthen the competitiveness of the tourism sector, increase the competitiveness of agriculture and agribusiness, and improve the business-enabling environment at the municipal level. ACTIVITIES The project provides assistance to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, local tourist organizations, and business support service providers, as well as municipal governments to stimulate private sector growth. The project is: Strengthening the competitiveness of the tourism sector It is promoting the north as a tourist destination by supporting innovative service providers, building the region’s capacity to support tourism, assisting coordination with coastal tourism businesses, and expanding access to tourist information. Improving the viability of agriculture and agribusiness It is restoring agriculture as a viable economic activity by supporting agricultural producers and processors from the north to capitalize on market trends and generate more income. Bettering the business-enabling environment It is identifying barriers to doing business and assisting municipalities to execute plans to lower these obstacles by providing services and targeted investment. RESULTS 248 businesses have received assistance from Economic Growth Project (EGP)-supported activities. Sales of items produced by EGP-supported small businesses have increased by 15.8 percent since the project began. Linkages have been established between 111 Northern firms, as well as between Northern firms and Central and Southern firms. 26 EGP-assisted companies invested in improved technologies, 29 improved management practices, and 31 farmers, processors, and other firms adopted new technologies or management practices. -

Territorial Area of Montenegro Municipalities

14/10/2013 Legal and political context of ANALYSIS Montenegro of the legal status and • Independent, autonomous, internationally functioning of public recognized country • As per its state organization, Montenegro is a authority entities in simple country principally financed by the EU the by financed principally Montenegro • As per its type of government , Montenegro is a Republic A joint initiative of the OECD and the European Union, European the and OECD the of initiative A joint • As per its political regime, it is a democratic Prof.dr Đorđije Blažić country, as well as an ecological, social justice and International Benchmarking Seminar rule of law country Danilovgrad, Montenegro 9-11 October 2013 • As per its power organization, i.e. the power division system (legislative executive and judicial 2 © OECD power) Number and structure of Territorial area of Montenegro municipalities Crna Gora Andrijevica Bar Berane Bijelo Polje Budva Danilovgrad Žabljak Kolašin Kotor Mojkovac Montenegro Broj mjesnih Broj opština Broj naselja Gradska naselja 13 812 283 598 717 924 122 501 445 897 335 367 zajednica Number of Number of Urban Number of local municipalities settlements settlements communities Herceg Nikšić Plav Plužine Pljevlja Podgorica Rožaje Tivat Ulcinj Cetinje Šavnik Novi 21 1,256 40 368 2 065 486 854 1 346 1 441 432 46 255 235 910 553 3 4 Land and coastal boundaries (Coast Srednja mjesečna temperatura vazduha line) AVERAGE MONTHLY AIR TEMPERATURE (º C) Srednja Kopnena granica prema / Land boundary with godišnj a Hrvatskoj B i H Srbiji -

Lista Ponuđača (2019. Godina)

Redni Ime i prezime Naziv ponuđača Sjedište Država broj odgovornog lica Elektroenergetski koordinacioni Vojvode Stepe 412, 1 Srbija Miroslav Vuković centar doo Beograd Beograd 2 Vekom Mont Doo Podgorica ul. 27. Marta br.46 Crna Gora Sanja Plemić 3 Žitomlin doo Nikšić Miločani doo Nikšić Crna Gora Stanojka Nikolić 4 Urbi pro doo Podgorica ul. Radosava Burića Crna Gora Dušan Džudović 5 PNP Perošević doo Bijelo Polje ul. III Sandžačka bb Crna Gora Zorica Perošević Svetlana Aksenova 6 Svetlana Aksenova Mihajlovna Polje bb Bar Crna Gora Mihajlovna 7 "AUTO RAD” doo Podgorica Bioče bb Crna Gora Meser Tehnogas AD Beograd- 8 ulica Vuka Karadžića bb Crna Gora Fabrika Nikšić 9 GLOSARIJ PODGORICA ul. Vojislavljevića 76 Crna Gora Mirjana Mijušković 10 Bombeton doo Cetinje ul. Peka Pavlovića 56 Crna Gora 11 Veletex doo Podgorica Cijevna bb Crna Gora Miloš Golubović ul. Serdara Jola Piletića 12 Hifa oil doo Podgorica Crna Gora Nemanja Mrdak br.8/6 13 Hasko Company doo Rožaje Besnik bb Crna Gora Omer Murić 14 Brojni Laz doo Rožaje Honsiće bb Crna Gora Šefkija Honsić 15 Braća Honsić doo Rožaje Honsiće bb Crna Gora Reko Honsić 16 Strmac doo Rožaje Biševo bb Crna Gora Safet Avdić 17 Fikro - Tours MNE doo Rožaje Bukovica bb Crna Gora Fikret Ibrahimović ul. Đoka Miraševića, 18 G-tech doo Podgorica Crna Gora Rade Gogić Ruska Kula M1 Entrust Datacard Corporation 1187 Park Place Shakopee 19 Amerika Xavier Coemelck SAD MN 55379 USA 20 Dazmont doo Podgorica Trg Božane Vučinić 17 Crna Gora 21 Art Gloria Marka Radovića 20 Crna Gora Savo Đonović 22 Chip Doo Podgorica Crna Gora 23 Zavod za metrologiju Kralja Nikole br.2 Crna Gora Vanja Asanović 24 Autotamaris doo tivat Kukuljina bb Crna Gora Zorica Radonjić 25 Swiss Osiguranje A.D. -

Energy Efficient Municipality Bijelo Polje, Montenegro

Energy efficient municipality Bijelo Polje, Montenegro Lucija Rakocevic, MSc International training course on business planning for energy efficiency projects Background information . Montenegro ‒ Final energy consumption: 30 PJ Pljevlja ‒ Electricity (from hydro, coal and Plužine Žabljak Bijelo Polje import*) Mojkovac Šavnik Berane Rožaje ‒ Heat (wood based, light fuel oil, Nikši? LNG, coal) Kolašin Andrijevica ‒ Transport (fossil fuels, electricity) Danilovgrad Kotor Plav Cetinje ‒ Split into 21 municipalities Herceg Novi Podgorica Tivat Budva Bijelo Polje Bar ‒ 4th municipality by size Ulcinj ‒ One of the northern centers ‒ 4 % of all energy used in MNE ‒ Main economic sectors: services, processing industry, agriculture International training course on business planning for energy efficiency projects, UNECE, 20-21st June, 2013, Istanbul, Turkey Bijelo Polje . Energy consumption by different sectors and by type of energy source used . Public services use 4 % of all energy generation . Local government has legal obligations to: ‒ Manage energy under its responsibility ‒ Develop local plans (10 yr Energy and 3yrs EE plan) ‒ Follow obligation for energy El. energija Drvna goriva Lož ulje Pogonska goriva Ugalj characteristics in buildings 1200 ‒ Support households in 1000 implementation through info and giving an example 800 . Local government services TJ 600 ‒ 15 buildings and 7 heating 400 systems using light fuel oil ‒ Electricity and light fuel oil 200 ‒ Currently uses 2 % of local 0 budget for energy bills Domaćinstva Usluge Industrija -

Montenegro Ministry of Human and Minority Rights Podgorica, March

Montenegro Ministry of Human and Minority Rights REPORT on the implementation of the Strategy for Social Inclusion of Roma and Egyptians in Montenegro 2016 - 2020 for 2019 Podgorica, March 2020 CONTENT INTRODUCTORY SUMMARY 3 KEY ACHIEVEMENTS 6 Area 1. 6 Housing 6 Area 2. 7 Education 7 Area 3. 10 Health Care 10 Area 4. 12 Employment 12 Area 5. 17 Legal status 17 Area 6. 18 Social status and family protection 18 Area 7. 22 Culture, identity and information 22 RECOMMENDATIONS 75 APPENDICES 77 2 INTRODUCTORY SUMMARY The main goal of the Strategy for Social Inclusion of Roma and Egyptians in Montenegro 2016-2020 is "Social Inclusion of Roma and Egyptians through Improving the Socio-Economic Position of Members of this Population in Montenegro". The Strategy is implemented through one-year action plans. The most significant result achieved in 2019 in the field of housing within the Regional Housing Program during 2019, is the completion of implementation of subproject MNE 4: "Construction of 94 housing units in the municipality of Berane" whose construction began in 2017, and the occupancy by beneficiaries was completed on 26 March 2019, including two families from the Roma and Egyptian population who obtained two housing units. When it comes to education, the number of Roma and Egyptian students at all levels of education has increased, and support has been provided to parents and children to raise their awareness of the importance of education. In the field of health care, according to a CEDEM survey in mid- 2018, over 95% of the Roma population is covered with health insurance. -

Odluka O Opštinskim I Nekategorisanim Putevima Na Teritoriji Glavnog Grada - Podgorice

Odluka o opštinskim i nekategorisanim putevima na teritoriji Glavnog grada - Podgorice Odluka je objavljena u "Službenom listu CG - Opštinski propisi", br. 11/2009, 40/2015 i 34/2016. I OPŠTE ODREDBE Član 1 Ovom Odlukom se uređuje upravljanje, izgradnja, rekonstrukcija, održavanje, zaštita, razvoj i način korišćenja i finansiranja opštinskih i nekategorisanih puteva na teritoriji Glavnog grada - Podgorice (u daljem tekstu: Glavni grad). Član 2 Opštinski put je javni put namijenjen povezivanju naselja na teritoriji Glavnog grada, povezivanju sa naseljima u susjednim opštinama ili povezivanju djelova naselja, prirodnih i kulturnih znamenitosti, pojedinih objekata i slično na teritoriji Glavnog grada. Opštinski putevi su lokalni putevi, kao i ulice u naseljima. Opštinski putevi su putevi u opštoj upotrebi. Član 3 Nekategorisani put je površina koja se koristi za saobraćaj po bilo kom osnovu i koji je dostupan većem broju korisnika (seoski, poljski i šumski putevi, putevi na nasipima za odbranu od poplava, parkirališta i sl.). Nekategorisani putevi su u opštoj upotrebi, osim puteva koji su osnovno sredstvo privrednog društva ili drugog pravnog lica i puteva izgrađenih sredstvima građana na zemljištu u svojini građana. II ODREĐIVANjE OPŠTINSKIH I NEKATEGORISANIH PUTEVA Član 4 Prema značaju za saobraćaj i funkciji povezivanja u prostoru putevi na teritoriji Glavnog grada su kategorisani u: - opštinske puteve - lokalne puteve i ulice u naseljima i - nekategorisane puteve. Kategorizacija i način obilježavanja opštinskih puteva vrši se na osnovu mjerila za kategorizaciju koje utvrđuje Skupština Glavnog grada, posebnom odlukom. Kategorija planiranog opštinskog puta na osnovu mjerila iz prethodnog stava i propisa o uređenju prostora, određuje se planskim dokumentom Glavnog grada. Član 5 Odluku o određivanju i prekategorizaciji opštinskih i nekategorisanih puteva na teritoriji Glavnog grada donosi Skupština, shodno odluci iz člana 4 stav 2 ove odluke. -

Maloprodajni Objekti Izbrisani Iz Evidencije

Broj rješenja pod Naziv privrednog društva Sjedište Naziv maloprodajnog objekta Adresa maloprodajnog objekta Sjedište Datum do kojeg kojim je izdato privrednog maloprodajnog je važilo odobrenje društva objekta odobrenje 1-50/3/1-1 D.O.O.LEMIKO - IMPEX Ulcinj Restoran - Miško desna obala rijeke Bojane Ulcinj 14.11.2020. 1-50/4-1 D.O.O.Gitanes - export Nikšić Prodavnica Podgorički put bb - Straševina Nikšić 10.04.2016. 1-50/4/1-1 D.O.O.J.A.Z. Berane Kiosk Mojsija Zečevića bb Berane 14.04.2018. 1-50/5-1 D.O.O. Trio trade company Podgorica Kiosk - Trio 1 Vasa Raičkovića bb (objekat br.21, lok.br.21) Podgorica 10.04.2010. 1-50/5/1-1 D.O.O.Francesković Tivat Lounge bar - Restoran VOLAT Šetalište Iva Vizina br. 15 Tivat 12.03.2015. 1-50/5-2 D.O.O. Trio trade company Podgorica Kiosk - Trio 2 Vasa Raičkovića bb (objekat br.21,lok.br.21) Podgorica 10.04.2010. 1-50/6-1 D.O.O. Mamić Nikšić Prodavnica Duklo bb Nikšić 10.04.2012. 1-50/6/1-1 D.O.O.Sikkim Podgorica Restoran - kafe bar Mantra Ivana Milutinovića br. 21 Podgorica 13.03.2015. 1-50/7-1 A.D.Beamax Berane Prodavnica M.Zečevića br. 1 Berane 04.07.2011. 1-50/7/1-1 D.O.O.Rastoder company Podgorica Prodavnica Isidora Sekulića br.45 Podgorica 14.03.2015. 04-1-300/1-19 "HUGO" d.o.o. Podgorica Kafe bar HUGO Bokeška ulica br.10 Podgorica 29.05.2021. -

Medium–Term Programme

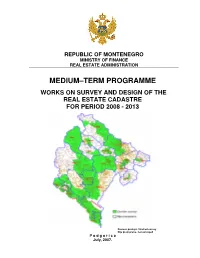

REPUBLIC OF MONTENEGRO MINISTRY OF FINANCE REAL ESTATE ADMINISTRATION MEDIUM–TERM PROGRAMME WORKS ON SURVEY AND DESIGN OF THE REAL ESTATE CADASTRE FOR PERIOD 2008 - 2013 Zavrsen premjer- finished survey Nije premjereno- not surveyed P o d g o r i c a July, 2007. Zavrsen premjer- finished survey Planiran premjer- planned survey Nije premjereno- not surveyed Pursuant to the Article 4 paragraph 1 of the Law on State Survey and Real Estate Cadastre (“Official gazette of the RoM”, No.29/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro has adopted at the Session, held on 26 th July 2007 MEDIUM-TERM PROGRAMME OF WORKS ON SURVEY AND DESIGN OF REAL ESTATE CADASTRE FOR PERIOD 2008 - 2013 I GENERAL TERMS It is stipulated by the Provision of the Article 4, paragraph 1 of the Law on State Survey and Real Estate Cadastre ("Official gazette of the RoM", No. 29/07) - hereinafter referred to as the Law, that works of state survey and design and maintenance of the real estate cadastre is performed on the base of medium-term and annual work programmes. Medium-term work programme for period 1 st January 2008 to 1 st January 2013 (hereinafter referred to as the Programme) directs further development of the state survey and real estate cadastre for the Republic of Montenegro in the next five years and it determines the type and scope of works, and the scope of funds for their realisation. Funds for realisation of the Programme are provided in accordance with the Article 176 of the Law. Annual work programmes are made on the base of the Programme.