Risk Factors for Nipah Virus Transmission, Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia: Results from a Hospital-Based Case-Control Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(PKPD) in the WHOLE DISTRICT of SEREMBAN EFFECTIVE: 9 JULY 2021 Unofficial English Translation by MGCC

MOVEMENT CONTROL ORDER SOP TIGHTENED (PKPD) IN THE WHOLE DISTRICT OF SEREMBAN EFFECTIVE: 9 JULY 2021 Unofficial English translation by MGCC Allowed Activities Effective 24 Hours Allowed Activity As per brief Residents Allowed with condition • One (1) representative from Period Period description Movement each house to purchase necessities. ACTIVITIES & PROTOCOLS • Necessary services (Essential Services). Action Brief Description Effective July 9, 2021 (12.01am) to July 22, 2021 (11.59pm) Non-Allowed Activities Period • Exiting house for activities Involved Areas • The entire district of Seremban, Negeri Sembilan other than those allowed (Mukim Ampangan, Mukim Labu, Mukim Lenggeng, Mukim Pantai, Mukim Rantau, Mukim without permission of Lasah, Mukim Seremban and Mukim Setul) PDRM. • Movement out of the *For PKPD in Taman Desaria (including Taman Desa Saga), Seremban Negeri Sembilan, please population. refer to the PKPD SOP currently in force. • Movement of outsiders into the EMCO area. Control • All routes PKPD entry and exit are closed. Movement • Control over the local area of infection is implemented by PDRM with help ATM, APM and RELA. Fixed Orders • All residents NOT ALLOWED TO EXIT from their respective homes / residences. • Subsection 11 (3) of Act 342. • Only one (1) representative from each house is allowed to buy necessities at the grocery • Subject to the ruling issued by store in the PKPD area within a radius 10 kilometers from the residence. the NSC and MOH. • Maximum three (3) people only including the driver allowed out for health care, medical • Other directions from time to and vaccination services. time issued by the Authorized • Movement across regions and states for the purpose of COVID-19 vaccination at Vaccination Officer under Act 342. -

Poster Sg Linggi

Variations of Ra-226, Ra-228 and K-40 activity concentrations along Linggi River Yii, M.W. and Zal U’yun Wan Mahmood Malaysian Nuclear Agency, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, MALAYSIA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Study presented the concentration distribution of Uncontrolled development and rapid Ra-226, Ra-228 and K-40 in sediment and water industrialization brought alarming level of and its variation related to the physical parameters pollutants into the aquatic environment. Water and suspended particles to find the dynamics of and sediment can be used as an indicator to these radionuclides along the river. Also, the determine the level of pollutants. According to changing trend of radionuclides activity along the Environment Quality Report 2006 by river will provide information of pollutants Department of Environment, even though Linggi movement from terrestrial to estuary. River in Negeri Sembilan is not categorized as very much polluted as several rivers, but it has OBJECTIVES been selected to be the study site because this •To find relation between radionuclides river lies within the catchment area of 1,250 concentration with physical parameters. kilometer square and it was used as one of the •To identify pollutants movement from terrestrial water supply intake point for Seremban, Rembau to estuary. and Port Dickson Districts. MATERIAL AND METHODS RESULTS Study Area Analyses flow Activity concentrations w in Water a t e r Activity concentrations in Sediment Physical Data of water S e d i m e n t Correlation of radionuclides in sample CONCLUSION Activity of radionuclides at some stations are found to be higher than the others mainly suggesting the input of radium (development and excavation of soil) and potassium (agriculture) is coming from human activities. -

Outcomes Following a Multi-Disciplinary Approach To

FX 01 Outcomes Following A Multi-Disciplinary Approach To Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstructive Surgery At Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar, Seremban: A Case Series 1Liew MY, 2Shamsudin Z, 2Nadarajah E, 3Kalimuthu M, 3Ebrahim R, 2Ahmad AR, 4Solayar GN 1Hospital Tuanku Ja'afar, Jalan Rasah, Bukit Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan 2Orthopaedics Department, Hospital Tuanku Ja'afar, Jalan Rasah, Bukit Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan 3Sports Medicine Department, Hospital Tuanku Ja'afar, Jalan Rasah, Bukit Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan 4Orthopaedics Department, International Medical University (IMU), Jalan Dr Muthu, Bukit Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan INTRODUCTION: There were no significant differences in Primary ACL reconstruction is an effective outcomes between patients with and without surgical treatment for ACL deficiencies, meniscal tears in this series. One patient had with satisfactory or better outcomes in 75% surgical site infection and 1 patient required to 97% of patients1. However, some studies revision surgery due to failed graft. suggest that up to 23% of these reconstructions may fail2. This case series DISCUSSIONS: aims to determine outcomes following Most patients in our series were satisfied arthroscopic ACL reconstruction at Hospital following ACL reconstruction with regards Tuanku Ja’afar, Seremban. to their function and pain scores. Patients who had poor or fair functional scores only METHODS: claimed to have difficulty performing very A total of 74 patients who underwent strenuous exercises. All patients were arthroscopic ACL reconstruction from followed up at the Orthopaedic outpatient January 2015 to December 2017 were clinic by their surgeon as well as team sports contacted. Only 50 patients were contactable physicians at our unit for further and included in this retrospective study. -

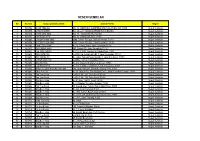

Negeri Ppd Kod Sekolah Nama Sekolah Alamat Bandar Poskod Telefon Fax Negeri Sembilan Ppd Jempol/Jelebu Nea0025 Smk Dato' Undang

SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH NEGERI SEMBILAN KOD NEGERI PPD NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX SEKOLAH PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0025 SMK DATO' UNDANG MUSA AL-HAJ KM 2, JALAN PERTANG, KUALA KLAWANG JELEBU 71600 066136225 066138161 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD SMK DATO' UNDANG SYED ALI AL-JUFRI, NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0026 BT 4 1/2 PERADONG SIMPANG GELAMI KUALA KLAWANG 71600 066136895 066138318 JEMPOL/JELEBU SIMPANG GELAMI PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6001 SMK BAHAU KM 3, JALAN ROMPIN BAHAU 72100 064541232 064542549 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6002 SMK (FELDA) PASOH 2 FELDA PASOH 2 SIMPANG PERTANG 72300 064961185 064962400 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6003 SMK SERI PERPATIH PUSAT BANDAR PALONG 4,5 & 6, GEMAS 73430 064666362 064665711 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6005 SMK (FELDA) PALONG DUA FELDA PALONG 2 GEMAS 73450 064631314 064631173 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6006 SMK (FELDA) LUI BARAT BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064676300 064676296 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6007 SMK (FELDA) PALONG 7 FELDA PALONG TUJUH GEMAS 73470 064645464 064645588 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6008 SMK (FELDA) BANDAR BARU SERTING BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064581849 064583115 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6009 SMK SERTING HILIR KOMPLEKS FELDA SERTING HILIR 4 72120 064684504 064683165 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6010 SMK PALONG SEBELAS (FELDA) FELDA PALONG SEBELAS GEMAS 73430 064669751 064669751 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6011 SMK SERI JEMPOL -

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

Negeri Sembilan

MALAYSIA LAPORAN SURVEI PENDAPATAN ISI RUMAH DAN KEMUDAHAN ASAS MENGIKUT NEGERI DAN DAERAH PENTADBIRAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND BASIC AMENITIES SURVEY REPORT BY STATE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT NEGERI SEMBILAN 2019 Pemakluman/Announcement: Kerajaan Malaysia telah mengisytiharkan Hari Statistik Negara (MyStats Day) pada 20 Oktober setiap tahun. Tema sambutan MyStats Day 2020 adalah “Connecting The World With Data We Can Trust”. The Government of Malaysia has declared National Statistics Day (MyStats Day) on 20th October each year. MyStats Day theme is “Connecting The World With Data We Can Trust”. JABATAN PERANGKAAN MALAYSIA DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS, MALAYSIA Diterbitkan dan dicetak oleh/Published and printed by: Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia Department of Statistics, Malaysia Blok C6, Kompleks C Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62514 Putrajaya MALAYSIA Tel. : 03-8885 7000 Faks : 03-8888 9248 Portal : https://www.dosm.gov.my Facebook/Twitter/Instagram : StatsMalaysia Emel/Email : [email protected] (pertanyaan umum/general enquiries) [email protected] (pertanyaan & permintaan data/data request & enquiries) Harga/Price : RM30.00 Diterbitkan pada July 2020/Published on July 2020 Hakcipta terpelihara/All rights reserved. Tiada bahagian daripada terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula, disimpan untuk pengeluaran atau ditukar dalam apa-apa bentuk atau alat apa jua pun kecuali setelah mendapat kebenaran daripada Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. Pengguna yang mengeluarkan sebarang maklumat dari terbitan ini sama ada yang asal atau diolah semula hendaklah meletakkan kenyataan berikut: “Sumber: Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia” No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means or stored in data base without the prior written permission from Department of Statistics, Malaysia. -

Public Summary Report Sime Darby Plantation Sdn. Bhd

PF441 RSPO Public Summary Report Revision 1 (Sept/2014) RSPO – 1st Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA1-1) Public Summary Report Sime Darby Plantation Sdn. Bhd. Head Office: Level 3A, Main Block, Plantation Tower, No 2 Jalan P.J.U 1A/7 47301 Ara Damansara, Selangor, Malaysia. Certification Unit: Strategic Operating Unit (SOU 14) – Tanah Merah Palm Oil Mill 71709 Port Dickson Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Page 1 of 59 PF441 RSPO Public Summary Report Revision 1 (Sept/2014) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No SECTION 1: Scope of the surveillance Assessment..................................................................... 3 1. Company Details.............................................................................................................................. 3 2. RSPO Certification Information & Other Certifications......................................................................... 3 3. Location(s) of Mill & Supply Base...................................................................................................... 3 4. Description of Supply Base............................................................................................................... 4 5. Plantings & Cycle………………………………………………………………………………………................................... 4 6. Certified Tonnage…………….………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 SECTION 2: Assessment Process….............................................................................................. 5 Certification Body.……………………………………………………………..………………………………………………………….. 5 Assessment Methodology, -

(CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices

‘Annex 26’ Contact Details of the National Crisis Preparedness & Response Centre (CPRC), Disease Control Division, the State Health Departments and Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) Representative of the District Health Offices National Crisis Preparedness and Response Centre (CPRC) Disease Control Division Ministry of Health Malaysia Level 6, Block E10, Complex E 62590 WP Putrajaya Fax No.: 03-8881 0400 / 0500 Telephone No. (Office Hours): 03-8881 0300 Telephone No. (After Office Hours): 013-6699 700 E-mail: [email protected] (Cc: [email protected] and [email protected]) NO. STATE 1. PERLIS The State CDC Officer Perlis State Health Department Lot 217, Mukim Utan Aji Jalan Raja Syed Alwi 01000 Kangar Perlis Telephone: +604-9773 346 Fax: +604-977 3345 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kangar District Health Office: Dr. Zulhizzam bin Haji Abdullah (Mobile: +6019-4441 070) 2. KEDAH The State CDC Officer Kedah State Health Department Simpang Kuala Jalan Kuala Kedah 05400 Alor Setar Kedah Telephone: +604-7741 170 Fax: +604-7742 381 E-mail: [email protected] RAT Representative of the Kota Setar District Health Office: Dr. Aishah bt. Jusoh (Mobile: +6013-4160 213) RAT Representative of the Kuala Muda District Health Office: Dr. Suziana bt. Redzuan (Mobile: +6012-4108 545) RAT Representative of the Kubang Pasu District Health Office: Dr. Azlina bt. Azlan (Mobile: +6013-5238 603) RAT Representative of the Kulim District Health Office: Dr. Sharifah Hildah Shahab (Mobile: +6019-4517 969) 71 RAT Representative of the Yan District Health Office: Dr. Syed Mustaffa Al-Junid bin Syed Harun (Mobile: +6017-6920881) RAT Representative of the Sik District Health Office: Dr. -

Towards Balanced and Sustained Economic Growth

VOL. 3 ISSUE 1, 2021 07 HIGH IMPACT PROJECTS OF STATE STRUCTURE PLAN OF NEGERI SEMBILAN2045– TOWARDS BALANCED AND SUSTAINED ECONOMIC GROWTH *Abdul Azeez Kadar Hamsa, Mansor Ibrahim, Irina Safitri Zen, Mirza Sulwani, Nurul Iman Ishak & Muhammad Irham Zakir Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kulliyyah of Architecture and EnvironmentalDesign, International Islamic University Malaysia ABSTRACT METHODOLOGY Figure 1 shows the process in the preparation of State Structure Plan This article is a review of Negeri Sembilan Draft State Structure Plan 2045. State structure plan sets the framework for the spatial planning and development to be translated in more detail in the next stage of development planning which is local plan. The review encompasses the goal, policies, thrusts and proposals to lead the development of Negeri Sembilan for the next 25 years. This review also highlights 9 high-impact projects proposed to be developed in Negeri Sembilan at the state level by 2045 through 30 policies and 107 strategies. Keywords: Structure plan, spatial planning, local plan, development thrust, Literature Review Negeri Sembilan * Corresponding author: [email protected] Preparation of Inception Report INTRODUCTION Sectors covered: State Structure Plan is a written statement that sets the framework for the spatial - Land Use - Public facilities planning and development of the state as stated in Section 8 of Town and - Socio economy - Infrastructure and utilities Country Planning Act (Act 172). The preparation of Negeri Sembilan Structure - Population - Traffic and transportation Plan 2045 is necessary to be reviewed due to massive economic development - Housing and settlement - Urban design change and the introduction of new policies at the national level over the past 20 - Commercial - Environmental heritage years. -

ON Semiconductor Malaysia Sdn. Bhd

Certificate No.: 117771CC5-2012-AQ-USA-IATF Rev. 2 Valid until: 08 July, 2018 – 07 July, 2021 IATF Certificate No.: 0314577 This is to certify that the management system of ON Semiconductor Malaysia Sdn. Bhd. Lot 122, Senawang Industrial Estate, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, 70450 and, if applicable, the remote support locations as mentioned in the Appendix accompanying this Certificate has been found to conform to quality management system standard: IATF 16949:2016 This certificate is valid for the following Scope: DESIGN AND MANUFACTURE OF SEMICONDUCTORS Place and date: For the issuing office: Katy, TX. 25 September 2019 DNV GL - Business Assurance Katy, TX, USA Robert Kozak Management Representative Lack of fulfilment of conditions as set out in the Certification Agreement may render this Certificate invalid. ACCREDITED UNIT: DNV GL - Business Assurance, 1400 Ravello Drive, Katy, TX 77449. Tel.: 281-396-1000. www.dnvglcert.com Page 1 of 4 Certificate No.: 117771CC5-2012-AQ-USA-IATF Rev. 2 IATF Certificate No.: 0314577 Place and date: Katy, TX. 25 September 2019 Appendix to Certificate ON Semiconductor Malaysia Sdn. Bhd. Remote Support Locations included in the certification are as follows: Name Address RSL Activities Certification Body ON Semiconductor Bang Pa-In industrial Est (FZ) Product Design, Supplier DNV GL (Thailand) Co. Ltd. 605-606 Moo 2, T Klongjig Management Amphur Bang Pa-In, Thailand ON Semiconductor Room 1407-1409, 1502-1505, Customer Service, Sales, DNV GL (Shenzhen) Ltd. 1507-1515, 15/F, News Strategic Planning Building, No. 2, Shennan Rd., Mid, Shenzhen, China ON Semiconductor Tower 115, Pribinova 25, Product Design DNV GL Slovakia a.s. -

New City Master Plan

KEY NEW CITY MASTER PLAN Forest Reserve MALAYSIA VISION VALLEY, NEGERI SEMBILAN, MALAYSIA Riparian Corridor Rural Reserve Indigenous Native Reserve Urban Design & Master Planning Existing Quarry/Landfill 1 Lawrence A. Chan FAIA/Boston Design Group Boston, Massachusetts USA Low Density Low-Medium Density Medium Density Consultant Collaborators: High Density Landscape Architecture Parks 1 Klopfer Martin Design Group Boston, Massachusetts USA Urban Planning Utile Boston, Massachusetts USA 9 Bukit Galla Forest Reserve Infrastructure Planning & Engineering BuroHappold Engineering London UK 1 8 Client: 1 SUPERGLADE Sdn Bhd Petaling Jaya, Malaysia 7 1 Project “Mountain-To-The-Sea” Greenway A 30-year master plan completed in March 2017 for a new city for 2 million people on 11,000 hectares of former palm plantation land in Malaysia Vision LEGEND 4 Valley (MVV), a 156,000-hectare development zone to: advance the socio- 1 High-tech corporate office/light 6 economic position of the 60-year-old nation; promote the wellbeing of its industrial mixed-use 4 5 multi-cultural, multi-ethnic citizens; and provide expansion of Kuala Lumpur. 2 High-density Central Business District 2 Objectives include: 3 Integrated Transportation Terminal 3 11 • Create an environment that advances urbanity, social and cultural 4 550-acre Jijan Riverway integration and cooperation, and a sustainable quality of life for living, 5 Confluence Lake 6 1,000-acre Central Park 10 working, recreation, and enjoying nature 9 7 West Hill Park 8 • Address natural and environmental challenges, including: a varied and 8 High speed rail to Kuala Lumpur and often extremely steep topography; safeguarding permanent forest Singapore reserves and natural habitats; preserving and enhancing riparian corridors; 9 Commuter rail 11 reducing Malaysia’s carbon footprint; and expanding renewable energy 10 Express train to airport resources 11 Sports and recreation mixed-use district The new city will serve as a destination hub for international travel, 10 9 12 Campus and institutional commerce, recreation, and eco-tourism. -

Negeri Sembilan

NEGERI SEMBILAN Bil No. Est. Nama syarikat/ pemilik Alamat Premis Negeri 1 W00594 CHAN YING SAI NO. 54, LORONG 3, KAMPONG RATA,JALAN BAHAU, 72100 Negeri Sembilan 2 W00595 CHIN HON KEE NO. 26 & 27 TAMAN SORNAM,72100 BAHAU Negeri Sembilan 3 W00596 CHEW ANG NGA NO. 11, TAMAN SATELIT,72100 Negeri Sembilan 4 W00597 CHEW AH LEEK NO. 32 TAMAN SATELIT,72100 Negeri Sembilan 5 W00667 CHEOH THIAN SING 6296, Taman PD Jaya,Jalan Seremban, 71010 Negeri Sembilan 6 W00668 CHEOH THIAN SING 6297, Taman PD Jaya, Jalan Seremban, 71010 Negeri Sembilan 7 W00669 PANG KOK SUNG No 19, Taman Naga, Jalan Seremban,71010 Negeri Sembilan 8 W00670 SIA CHENG KION 567, Taman PD, Jalan Seremban,71010 Negeri Sembilan 9 W00671 LEE POH CHUAN N0. 2, Lot 6005,Taman Tun Sambanthan,71010 Negeri Sembilan 10 W00672 DEE SONG FEI Lot 74B, Kg. Kuala Lukut,Bt. 3, Jalan Seremban ,71010 Negeri Sembilan 11 W00673 DEE SONG FEI No. 4968, Taman Pantai Mas,Bt. 2, Jalan Seremban ,71010 Negeri Sembilan 12 W00674 CHEOK KIAN SIN Lot 5742, Taman Pantai Mas,71000 Negeri Sembilan 13 W00684 Ong Yip Ming No.614, Oakland Commercial Center, 70300 Negeri Sembilan 14 W00685 Law Siong Deng No.17,Lot 4764, Jalan Nilam 2,Taman Jayamas 70300 Negeri Sembilan 15 W00686 Aeries PureBird Nest 9M) Sdn. Bhd 280, Jalan Haruan 1,Oakland Industrial Park,70300 Negeri Sembilan 16 W00687 Chan Poh Tat No 10, tingkat 1&2, Taman Bukit Emas, Jalan Seremban-Tampin, 70300 Negeri Sembilan 17 W00688 Yap Yew Siong Lot 5327,No. 233, Desa Resah,70000 Negeri Sembilan 18 W00689 Yap Yew Siong Lot 5327,No.