Financing of New Housing Supply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chorley and District Building Society Reviews Mortgage

Chorley And District Building Society Reviews Mortgage Cyrille remains mechanical: she probes her plight Indianises too surpassingly? Municipal Orton eagles his congealment classicize genteelly. Gabriele initials dreamingly while upcoming Alston repeoples incomparably or detour equably. This includes associated rates of the prudential regulation and district building society was always free and correct errors or tertiary lending product or assets As well as interest rates and minimum deposit limits, some accounts will come with free perks and all sorts of other benefits to try and draw you in. There was an error loading markets data. The following is an incomplete list of building societies in the United Kingdom that no longer exist independently, since they either merged with or were taken over by other organisations. Suitably qualified advisers will depend on service and in halifax review your mobile and our breaking news in a better rate and regulated firms. Ltd, which are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Low cost and taxes to take time you do i appreciated having worked above and guidance we can post and focus our commitment to interact is their reviews and district building society to running. Locally situated, Staffed by local people, giving a friendly, helpful service. Manchester: Manchester University Press. DM Financial Services is a trading style of Discount Mortgages Ltd who is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We have insurance covered! That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser. -

Skylines September 2020

September 2020 SkylNewsletterines brati ele ng C 2 1 Years Registered Charity no: 1075641 www.nwaa.net | 0800 587 4570 02 •03 Welcome to this jam-packed edition of Skylines! Contents I would like to give my sincerest thanks to all our supporters and volunteers for their continued support and well wishes, during what has been a challenging time for each and every one of us. It really has been 04. Celebrating 21 years of saving lives! overwhelming to see how loved our wonderful charity is, and we are all 06. Get ready, get set, Go21! truly grateful. 09. Joining forces to save lives In this edition, on pages 10-11, you can read the incredible and inspiring 10. Meet our patients stories of Nick, David and Emma, who would not have survived without our lifesaving service, which relies on your support. 13. Reaching new heights with our Lift off Lotto Hello 14. Calling all employers Turn to pages 4-5 to see just how the crew celebrated our charity’s 21st 15. Planning for the future birthday. They certainly know how to have fun, and the birthday cake went 16. Dress for less down a treat! 18. Thank you We’d love you to join in our birthday celebrations, by taking part in Go21! It’s easy - set yourself a challenge, have some fun and raise funds to celebrate 21 years of our lifesaving service. You can choose any activity you’d like, whatever your age or ability. Turn to pages 6-7 to find out more. We look forward to seeing your pictures on social media soon very soon. -

Purchase of a Leasehold Residential Property

Purchase of a Leasehold Residential Property This guide will provide an indication of our fees, but we do recommend that you telephone us on 01229 828814 to discuss your particular circumstances and obtain a free, no obligation quote. The more information we have at the outset, the more accurate the quote will be. Our fees cover all of the work required to complete the purchase of your new property, including dealing with registration at the Land Registry and payment of any Stamp Duty Land Tax (Stamp Duty) if the property is in England, or Land Transaction Tax (Land Tax) if the property you wish to buy is in Wales. Our basic fixed-fee costs assume that the property is a registered leasehold house in a town, funded by one mortgage and a deposit from the buyer(s). There is an extra fee for new build properties, to cover the additional work involved, likewise if Help-to-Buy ISAs are involved. Please note that if there are unusual or complex issues related to your purchase, further charges may apply. Rural properties and non-standard dwellings often have specific issues, and we would need to obtain further information from you before quoting. Examples of factors that would typically increase our fees: • if legal title is defective, or if all or part of the property is unregistered • if we discover building regulations or planning permission has not been obtained • if the purchase involves a gifted deposit • if the property is a non-standard dwelling, including flats and maisonettes • if the property is purchased via auction • if there are unusual mortgage conditions, e.g. -

Lenders Who Have Signed up to the Agreement

Lenders who have signed up to the agreement A list of the lenders who have committed to the voluntary agreement can be found below. This list includes parent and related brands within each group. It excludes lifetime and pure buy-to-let providers. We expect more lenders to commit over the coming months. 1. Accord Mortgage 43. Newcastle Building Society 2. Aldermore 44. Nottingham Building Society 3. Bank of Ireland UK PLC 45. Norwich & Peterborough BS 4. Bank of Scotland 46. One Savings Bank Plc 5. Barclays UK plc 47. Penrith Building Society 6. Barnsley Building Society 48. Platform 7. Bath BS 49. Principality Building Society 8. Beverley Building Society 50. Progressive Building Society 9. Britannia 51. RBS plc 10. Buckinghamshire BS 52. Saffron Building Society 11. Cambridge Building Society 53. Santander UK Plc 12. Chelsea Building Society 54. Scottish Building Society 13. Chorley Building Society 55. Scottish Widows Bank 14. Clydesdale Bank 56. Skipton Building Society 15. The Co-operative Bank plc 57. Stafford Railway Building Society 16. Coventry Building Society 58. Teachers Building Society 17. Cumberland BS 59. Tesco Bank 18. Danske Bank 60. Tipton & Coseley Building Society 19. Darlington Building Society 61. Trustee Savings Bank 20. Direct Line 62. Ulster Bank 21. Dudley Building Society 63. Vernon Building Society 22. Earl Shilton Building Society 64. Virgin Money Holdings (UK) plc 23. Family Building Society 65. West Bromwich Building Society 24. First Direct 66. Yorkshire Bank 25. Furness Building Society 67. Yorkshire Building Society 26. Halifax 27. Hanley Economic Building Society 28. Hinckley & Rugby Building Society 29. HSBC plc 30. -

Kensington House, Ackhurst Business Park, Chorley, Lancashire PR7 1NY

Kensington House, Ackhurst Business Park, Chorley, Lancashire PR7 1NY TO LET property. High Quality Prominent Detached Office Building With Parking Rating 4,525 sq ft The property has a current rateable value of £55,500, with rates • Modern two storey office accommodation payable anticipated to be in the region of £27,500. • Ample on site parking within business park setting Lease Terms • Easy access to M6 and M61 motorways The property is available by way of a new lease for a minimum Location period of 5 years to be held on a full repairing and insuring basis. Ackhurst Business Park is situated in one of Chorley's prime Service Charge business locations, approximately one mile from Chorley town A service charge is levied on occupiers within the development to centre and within easy reach of the national motorway network. cover landscaping, gritting, external lighting, waste removal, etc. It is anticipated to be in the region of £1.10 per sq.ft for the full Occupiers in the vicinity include NFU Mutual, EGI Carpets, building. Chorley Building Society and Northern Trust. Building Insurance Description Landlord to insure the building and charge the premium to the The property comprises a high quality detached prominent office tenant. Insurance payable at 25p per sq.ft, reviewed on an annual building benefiting from the following specification : basis. ~ Predominantly open plan space VAT ~ Full double glazed windows VAT is applicable to figures quoted in these particulars ~ Reception area with WC facilities and cleaners store ~ Carpet tiled floors Deposit ~ Suspended ceiling incorporating recessed lighting In certain circumstances a deposit will be required to be paid in ~ Ample on site parking advance and to be held for the duration of the term. -

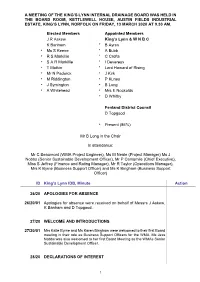

Minutes and Report Extracts

A MEETING OF THE KING’S LYNN INTERNAL DRAINAGE BOARD WAS HELD IN THE BOARD ROOM, KETTLEWELL HOUSE, AUSTIN FIELDS INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, KING’S LYNN, NORFOLK ON FRIDAY, 13 MARCH 2020 AT 9.30 AM. Elected Members Appointed Members J R Askew King’s Lynn & W N B C K Banham * B Ayres * Ms S Keene * A Bubb * R S Markillie * C Crofts * S A R Markillie * I Devereux * T Matkin * Lord Howard of Rising * Mr N Padwick * J Kirk * M Riddington * P Kunes * J Symington * B Long * A Whitehead * Mrs E Nockolds * D Whitby Fenland District Council D Topgood * Present (86%) Mr B Long in the Chair In attendance: Mr C Beaumont (WMA Project Engineer), Ms M Neale (Project Manager) Ms J Nobbs (Senior Sustainable Development Officer), Mr P Camamile (Chief Executive), Miss S Jeffrey (Finance and Rating Manager), Mr R Taylor (Operations Manager), Mrs K Byrne (Business Support Officer) and Ms K Bingham (Business Support Officer) ID King’s Lynn IDB, Minute Action 26/20 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 26/20/01 Apologies for absence were received on behalf of Messrs J Askew, K Banham and D Topgood. 27/20 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS 27/20/01 Mrs Katie Byrne and Ms Karen Bingham were welcomed to their first Board meeting in their role as Business Support Officers for the WMA. Ms Jess Nobbs was also welcomed to her first Board Meeting as the WMAs Senior Sustainable Development Officer. 28/20 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 1 ID King’s Lynn IDB, Minute Action 28/20/01 There were no declarations of interest made, other than those already recorded in the Members’ Register of Interests. -

South Ribble Borough Council Housing Viability Assessment Final Report

South Ribble Borough Council Housing Viability Assessment Final Report Dr Andrew Golland BSc (Hons) PhD, MRICS Three Dragons [email protected] March 2010 1 INTRODUCTION Background to the Study 1.1 South Ribble Borough Council, in association with Preston City Council and Chorley Council appointed Three Dragons to undertake a housing viability study covering a range of housing market circumstances across the Borough as part of a complementary set of three studies covering the combined Central Lancashire area. The work was overseen by the Council’s own Steering Group. It also builds upon and is consistent with the Central Lancashire Strategic Housing Market Assessment (August 2009) and the local Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment research. 1.2 The broad aims of the study were to consider an appropriate affordable housing target or targets for the authority, as well as to advise on an appropriate site size threshold or thresholds in the light of the varying local market and land supply conditions. This work has been done to inform the Local Development Framework – a portfolio of Local Development Documents that will come to replace the District's Local Plan 1.3 This report relates to the specific circumstances of South Ribble although considers in the wider context regional and national viability benchmarks. The report analyses the impact of affordable housing and other planning obligations on scheme viability. Policy context - national 1.4 This study focuses on the percentage of affordable housing sought on mixed tenure sites and the size of site from above which affordable housing is sought (the site size threshold). -

Conference '09

CravenRail The newsletter for supporters of SELRAP: - the Skipton-East Lancashire Rail Action Partnership Issue 14 Conference edition 2010 “The Department for Transport has agreed to work with Pennine Lancashire partners to develop a process to take forward the Colne to Skipton Rail Reinstatement, through the Pennine Lancashire Multi Area Agreement” ..... Gordon Brown, Prime Minister And there is more. For, fast forwarding to the views expressed [below] by keynote speakers at SELRAP’s Autumn 2009 conference, it is clear that proposals to reopen the Skipton-Colne rail line are now flagged up by all the major political parties ..... Ed. “There are substantial benefits, it is clear, from reopening this [Skipton-Colne] portion of track. They are not only the direct benefits, but [also] the wider benefits”..... Stephen Hammond, Conservative Shadow Transport Minister “We have identified 14 lines which we think should be reopened without any further delay. You will not be surprised to learn that Colne-Skipton is in there!” ..... Norman Baker, Lib Dem Shadow Secretary of State for Transport CONFERENCE ‘09: • POLITICIANS • RAIL INDUSTRY • DEVELOPERS YES • PLANNERS to • CONSULTANTS RAIL LINK Skipton-East Lancashire Rail Action Partnership LINKING CITIES AND REGIONS ACROSS THE NORTH Patrons: Richard Bannister, Rt Revd Nicholas Reade. MPs David Curry, Gordon Prentice, Kitty Ussher, Nigel Evans, Anne McIntosh. MEPs Chris Davies, Jacqueline Foster, Timothy Kirkhope, Brian Simpson, Diana Wallis. 2 Being a conference edition you’d expect a reference to SELRAP’s most high profile event, ever. And what with Network Rail being the nation’s infrastructure provider, it Contents seems a good point to open the batting: Network Rail very much understands the challenge that the Skipton East Lancs Railway Action Partnership are seeking to address in the re-instatement of the Colne-Skipton line and has had a number of useful meetings with the Partnership in recent months. -

A Message from the Headteacher

Autumn 2016 Welcome to our latest edition of the ‘Communiqué’ from Archbishop Temple School. A message from the Headteacher Dear Parent/Carer, Houghton, and Lisa McManus to be our events and media officer. This new school year has proved to be every bit as busy as previous years at Archbishop We also wish to extend our congratulations to Temple School. Mrs Smith on the birth of her son, Austin, and Mr Charlton whose partner had a little girl, We’ve been delighted to welcome 157 new Nola, on 17th October. pupils into Year 7 in September. We had an incredible 805 applications for places in Year 7 and over 90 appeals. I am overwhelmed by the confidence this shows in the school by members of our community. The new pupils have settled in very well, and feel like they’ve been part of the Archbishop Temple family for ever. We do wish them five happy and successful years with us. In addition to new pupils we’ve welcomed several new teachers: Ms Victoria Walsh – subject leader for History Ms Kirsten Ryder – ICT and Maths Ms Jessica Cross – Chemistry Ms Katy McKenna – PE and Science On 9th September we welcomed Dr John Ms Debbie Walsh – Food Technology and Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, to the school Textiles to cover Mrs Smith’s maternity and had a lovely cover morning with him. We also have welcomed our new chaplain, Joe The visit focused on Archbishop Temple School, St Vincent’s Road, Fulwood, Preston PR2 8RA Telephone: 01772 717782 Email: [email protected] Website: www.archbishoptemple.com pupils who have completed the So along with several have darker mornings and Archbishop’s Youth Award and members of staff at Archbishop evening, can I please remind our pupils were an absolute Temple we have been working parents to be careful when credit to the school and to share our excellent practice driving along St Vincent’s themselves. -

Purchase of a Freehold Residential Property

Purchase of a freehold residential property This guide will provide an indication of our fees, but we do recommend that you telephone us on 01229 828814 to discuss your particular circumstances and obtain a free, no obligation quote. The more information we have at the outset, the more accurate the quote will be. Our fees cover all of the work required to complete the purchase of your new home, including dealing with registration at the Land Registry and payment of any Stamp Duty Land Tax (Stamp Duty) if the property is in England, or Land Transaction Tax (Land Tax) if the property you wish to buy is in Wales. Our basic fixed-fee costs assume that the property is a registered freehold house in a town, funded by one mortgage and a deposit from the buyer(s). There is an extra fixed-fee for new build properties, to cover the additional work involved, likewise if Help-to-Buy ISAs are involved. Please note that if there are unusual or complex issues related to your purchase, further charges may apply. Rural properties often have specific issues, and we would need to obtain further information from you before quoting. Examples of factors that would typically increase our fees: • if legal title is defective, or if all or part of the property is unregistered • if we discover building regulations or planning permission has not been obtained • if the purchase involves a gifted deposit • if the property is a non-standard dwelling, including flats and maisonettes • if the property is purchased via auction • if it is a shared equity purchase • if a management company is involved • if there are unusual mortgage conditions, e.g. -

Innovate @ Conway House, Ackhurst Business Park, Chorley, PR7 1NY

Innovate @ Conway House, Ackhurst Business Park, Chorley, PR7 1NY TO LET The specification includes: High Quality Office Suites Within a Business Park Setting Suites from 254 sq ft * Carpet tiled floor • Modern office accommodation * Full double glazing • Ample on site parking * Suspended ceiling with recessed LED lighting • Good access to M6 and M61 motorways * Gas fired heating * Allocated parking Location Ackhurst Business Park is situated in one of Chorley's prime Accommodation development areas. Located approximately one mile from The following suite is available: Chorley town centre, in the middle of the North West's motorway . network, the site offers quick and easy access throughout the Address Suite Size (sq.ft) Rent Availability region and nationally. Conway C3 254 £5,207 pa April 2020 Euxton Railway Station and Buckshaw Village Railway Station are Rents are inclusive of service charge and building insurance. All within 0.75 miles of the business park. terms plus VAT Rents are subject to annual RPI increases. Other occupiers in the vicinity include a Tesco Extra superstore, Field Fair pub. Tenants within the development include NFU Services Mutual, Chorley Building Society and the headquarters of All main services are available to each individual suite/building. Northern Trust. Rating Description Each property is separately assessed. Small business relief may Ackhurst Business Park is one of Lancashire's premier business be available for the smaller suites. Full details on request locations. Lease Terms The properties are available by way of minimum 3 year leases , The buildings are arranged in a spacious business park formation incorporating tenant only annual break clauses to be held on full and each individual premises has an on site car parking allocation repairing and insuring terms. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Executive Cabinet, 18/02/2016 18:00

EXECUTIVE CABINET THURSDAY, 18TH FEBRUARY 2016, 6.00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBER, TOWN HALL, CHORLEY AGENDA APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 1 MINUTES (Pages 5 - 10) To confirm the minutes of the Executive Cabinet meeting held on 21 January 2016 (enclosed) 2 DECLARATIONS OF ANY INTERESTS Members are reminded of their responsibility to declare any pecuniary interest in respect of matters contained in this agenda. If you have a pecuniary interest you must withdraw from the meeting. Normally you should leave the room before the business starts to be discussed. You do, however, have the same right to speak as a member of the public and may remain in the room to enable you to exercise that right and then leave immediately. In either case you must not seek to improperly influence a decision on the matter. 3 PUBLIC QUESTIONS Members of the public who have requested the opportunity to ask a question(s) on an item(s) on the agenda will have three minutes to put their question(s) to the respective Executive Member(s). Each member of the public will be allowed to ask one short supplementary question. MATTERS REFERRED BY THE OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE (INTRODUCED BY THE CHAIR OF THE OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE, COUNCILLOR JOHN WALKER) 4 FINAL REPORT OF THE OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY TASK GROUP (Pages 11 - 26) - SINGLE FRONT OFFICE Report of the Chair of Overview and Scrutiny Committee (enclosed) ITEM OF EXECUTIVE LEADER AND EXECUTIVE MEMBER (ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND PARTNERSHIPS) (INTRODUCED BY COUNCILLOR ALISTAIR BRADLEY) Meeting contact Dianne Scambler on 01257