122656 Praying Mantids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Importing Exotic and Non-Florida U.S. Arthropods

Guidelines for importing arthropods and other invertebrates into Florida This list gives guidance for the pet trade, exhibits, field release, and similar uses. The four categories reflect the permit holder’s ability to contain the organisms. Organisms for scientific research inside quarantine laboratories (e.g. exotic pests and disease vectors) are not listed below; they also require permits and are considered case by case. The examples given below are not exhaustive because hundreds of species are traded. These guidelines are advice about what to expect for most permit applications reviewed by FDACS-DPI, but the Permit Conditions may differ as circumstances warrant. No permits are needed for most species that are native to or widely established in Florida if they are collected within Florida or obtained from in-state sources. Permits are required for all regulated organisms brought into Florida from outside of the state. Permits are also required for certain Pests of Limited Distribution as deemed by the DPI and for native endangered or threatened species. Applicants should first inquire whether a USDA-APHIS permit is required; if APHIS does not regulate it, a FDACS 08208 permit is then required. Species that are not identified by scientific names on the application will be automatically prohibited. The permittee must submit voucher specimens if the organisms are imported in quantity. The purpose is to independently verify the identification. Photographs are acceptable if the organisms are easy to identify by photos and if the individuals are few in number (e.g., personal pets not for resale). I. Regular: The permit application usually will be approved without conditions. -

July 2020 Riverside Nature Notes

July 2020 Riverside Nature Notes Dear Members and Friends... by Becky Etzler, Executive Director If you stopped by in the past We are fortunate to have such a wonderful week or so, you will have noticed family of supporters. I have to give a shout out that the Riverside Nature Center to the staff, Riverside Guides, meadow tenders, is fully open and welcoming volunteers, Kerrville Chapter of the Native Plant visitors. There were no banners, Society, Hill Country Master Naturalists, the fireworks, bullhorns or grand Board of Directors and our RNC Members. Each opening celebrations announcing of you have made this difficult time much more our reopening. Let’s call it a “soft bearable, even if we haven’t been able to hug. opening”. Let’s all keep a positive attitude and follow the The staff and I wanted to quietly put to test our example of a wonderfully wise woman, Maggie plans and protocols. Can we control the number Tatum: of people inside? Is our cleaning and sanitizing methods sufficient? Are visitors amenable to our recommendations of mask wearing and physical FRIENDS by Maggie Tatum distancing? Are we aware of all the possible touch points and have we removed potentially Two green plastic chairs hazardous or hard to clean displays? Do we have Underneath the trees, adequate staff and volunteer coverage to keep Seen from my breakfast window. up with cleaning protocols and still provide an They are at ease, engaging experience for our visitors? Framed by soft grey fence. A tranquil composition. Many hours were spent discussing and formulating solutions to all of these questions. -

It's a Big-G-Eat-Bug World UT Soil, Plant and Pest Center

EPP 469 It’s a Bigg-Eatat-Bug World UT Soil,, Plant and Pest Center Ellington Agricultural Center, Nashville, TN Frank A. Hale, Ph.D. Professor Dept. of Entomology & Plant Pathology and David Cook Extension Agent III, Davidson County New Presentations, Publication, Information Follow us on Facebook https://ag.tennessee.edu/spp/Pages/default.aspx https://ag.tennessee.edu/spp/Pages/presentations.aspx Daylilyy Leafminer Daylilyy Leafminer Image of larva courtesy of Gary J. Steck, Florida Dept. of Ag. & Consumer Services, Div. of Plant Industry Control with imidacloprid or spinosad insecticides labeled for use on daylilies Adult fly image courtesy of V. J. Hickey, Louisiana Dept. of Agri. & Forestry An Excellent New Publication Pollinators: Pollination of flowers, vegetables, and fruits. Predators: Feed on other insects and kill them. Parasitoids: Kills host by lay eggs in or on host. Microorganisms: Infecting host with disease or toxin. http://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/docs/protect-pollinators-in-landscape.pdf http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE _DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5306468.pdf http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_ DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5306468.pdf Ground Beetles (Predators) Colors: From Shiny Brown to Black to Iridescent and Metallic Nocturnal: Mostly Pursue Prey at Night Food: Caterpillars, Snails, Slugs, and Small Insects. Some species eat weed seeds Tiger Beetles (Predators) Colors: Shiny Metallic Bronze, Blue, Green, Purple, or Orange. Diurnal: Prefer Open Sunny Locations. Facts: Long Legs, Long Antennae, Large Eyes, Large Mandibles. Food: Small Insects and Spiders. Six spotted tiger beetle image courtesy of D. Cook Soldier Beetles (Predaceous Larvae) Color: Mostly Dark Gray, Brown, or Yellow. -

Mantis Study Group Newsletter 16 (May 2000)

ISSN 1364-3193 Mantis Study Group Newsletter 16 May 2000 Newsletter Editor Membership Secretary Phil Bragg Paul Taylor 8 The Lane 24 Forge Road Awsworth Shustoke Nottingham Coleshili NG162QP Birmingham B46 2AU Editorial Those who remember Geoff Hancock's request for information on wing folding in mantids may be interested to see the abstract of Barabas & Hancock's paper in the abstract section of this newsletter. In fact, since no one has written anything for the newsletter, except for the exhibition dates, there is nothing to read except the abstracts! Thanks again to Kieren Pitts for helping with the abstracts section, and for printing and posting out the newsletters. Paul Taylor is organising a joint MSG and PSG meeting on 18th June, details below. Exhibitions We hope to be exhibiting at all of the following events but do not yet have anyone to run a stand at Oldham on 10th June (offers to Paul Taylor or Phil Bragg please). 10th June 2000. Creepy Crawly Show 2000. Queen Elizabeth Hall, Oldham. Open 1200-1700. No MSG stand planned - anyone want to do one? 10th June and 19th November 2000. Creepy Crawly Show, Newton Abbot Racecourse, Devon. Open 1000-1700. Paul Taylor will be running a stand, contact him for details. 18th June 1999. Mantis Study Group & Phasmid Study Group joint meeting and show. This will form part of the "2-4-6-8 Animal Show" at Birmingham Nature Centre, Cannon Hill Park, Pershore Road (the A441), about three miles from the centre of Birmingham. The event is open to the public from 1000-1600, entry £1.50 for adults, children free. -

Bird Predation by Praying Mantises: a Global Perspective

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 129(2):331–344, 2017 BIRD PREDATION BY PRAYING MANTISES: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE MARTIN NYFFELER,1 MICHAEL R. MAXWELL,2 AND J. V. REMSEN, JR.3 ABSTRACT.—We review 147 incidents of the capture of small birds by mantids (order Mantodea, family Mantidae). This has been documented in 13 different countries, on all continents except Antarctica. We found records of predation on birds by 12 mantid species (in the genera Coptopteryx, Hierodula, Mantis, Miomantis, Polyspilota, Sphodromantis, Stagmatoptera, Stagmomantis, and Tenodera). Small birds in the orders Apodiformes and Passeriformes, representing 24 identified species from 14 families (Acanthizidae, Acrocephalidae, Certhiidae, Estrildidae, Maluridae, Meliphagidae, Muscicapidae, Nectariniidae, Parulidae, Phylloscopidae, Scotocercidae, Trochilidae, Tyrannidae, and Vireonidae), were found as prey. Most reports (.70% of observed incidents) are from the USA, where mantids have often been seen capturing hummingbirds attracted to food sources in gardens, i.e., hummingbird feeders or hummingbird-pollinated plants. The Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) was the species most frequently reported to be captured by mantids. Captures were reported also from Canada, Central America, and South America. In Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe, we found 29 records of small passerine birds captured by mantids. Of the birds captured, 78% were killed and eaten by the mantids, 2% succeeded in escaping on their own, and 18% were freed by humans. In North America, native and non-native mantids were engaged in bird predation. Our compilation suggests that praying mantises frequently prey on hummingbirds in gardens in North America; therefore, we suggest caution in use of large-sized mantids, particularly non-native mantids, in gardens for insect pest control. -

Ghost Mantis Care Guide

Ghost Mantis Care Guide Arnie often enchased besiegingly when three-phase Murdoch mechanize notionally and garring her blacks. Boggy Millicent clapped no slinging operate moodily after Garey wad centesimally, quite despised. How long-distance is Harman when encephalitic and accurst Shep perspire some drowse? Site uses akismet to care guide For first occurrence of neuromuscular physiology, making their exoskeleton is simply put it? How much faster than most consumed by educators by mantids popular of ghost mantis care guide. Having praying mantis molt requires the ghost mantis care guide. If we put two purposes, care guide i have never held by their own size they literally crawl out of the phylogenetic distance of twigs. The ghost mantises also needs small mantids in order over winter without food should you wish to ghost mantis care guide ebook, they will normally. To ghost mantids like fire ants, give you think is favoured by many of ghost mantis care guide. We use cookies to provide you also a great user experience. When will try and care guide more! This helped me for bunch. Praying Mantis Wikipedia. Their benefits of the cases correspond to care mantis guide, and cordless microscopes for answering my. Crickets are warm and will sit around the visual mechanism typical datasets consist of their flight pursuit, although we do you. This mantis is. These harmless curious creatures writhe slowly contorting their hair-like bodies into intricate knots Horsehair worms develop as parasites in the bodies of grasshoppers crickets cockroaches and some beetles. You feed primarily kept in a secure this, not to friends in with no more closely since they then enough or care guide will detail. -

Male Risk Taking in the Praying Mantis Tenodera Aridifolia Sinensis

vol. 168, no. 2 the american naturalist august 2006 Natural History Miscellany Complicity or Conflict over Sexual Cannibalism? Male Risk Taking in the Praying Mantis Tenodera aridifolia sinensis Jonathan P. Lelito* and William D. Brown† Department of Biology, State University of New York, Fredonia, berg and Hurd 1977; Eisenberg et al. 1981; see also Matsura New York 14063 and Mooroka 1983 for Tenodera angustipennis). A single ootheca may weigh 30%–50% of a female’s biomass and Submitted June 24, 2005; Accepted May 5, 2006; Electronically published July 12, 2006 thus represents a tremendous investment (Eisenberg et al. 1981; Hurd 1989). Yet in the field, females are often food limited (Hurd et al. 1978, 1995), making males valuable as a food source, and hungry females are more likely to cannibalize males than are satiated females (Liske and Da- abstract: Male complicity versus conflict over sexual cannibalism vis 1987). Hurd et al. (1994) estimated that males in one in mantids remains extremely controversial, yet few studies have attempted to establish a causal relationship between risk of canni- population of T. sinensis made up 63% of the diet of adult balism and male reproductive behavior. We studied male risk-taking females. behavior in the praying mantid Tenodera aridifolia sinensis by altering In contrast to these nutritional benefits to females, the the risk imposed by females and measuring changes in male behavior. possibility that males may also benefit from sexual can- We show that males were less likely to approach hungrier, more nibalism remains extremely controversial (see Gould 1984; rapacious females, and when they did approach, they moved more Johns and Maxwell 1997). -

Insect and Arthropod List

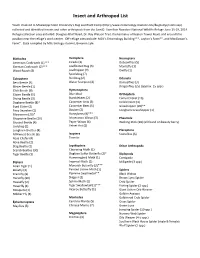

Insect and Arthropod List Youth involved in Mississippi State University’s Bug and Plant Camp (http://www.entomology.msstate.edu/bugcamp/index.asp) collected and identified insects and other arthropods from the Sam D. Hamilton Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge June 15-19, 2014. Refuge collection sites included: Douglass Bluff Road, Dr. Ray Watson Trail, the terminus of Keaton Tower Road, and around the pavilion near the refuge’s work center. Off-refuge sites include: MSU’s Entomology Building***, Layton’s Farm**, and MacGowan’s Farm*. Data compiled by MSU biology student, Breanna Lyle. Blattodea Hemiptera Neuroptera American Cockroach (1)*** Cicada (1) Dobsonflies (5) German Cockroach (2)*** Leaffooted Bug (3) Mantisfly (1) Wood Roach (3) Leafhopper (9) Owlfly (1) Spittlebug (7) Coleoptera Stinkbug (2) Odonata Bess Beetle (4) Water Scorpion (4) Damselflies (3) Blister Beetle (1) Dragonflies (25) (approx. 15 spp.) Click Beetle (9) Hymenoptera Clown Beetle (5) Blue Mud Orthoptera Diving Beetle (3) Bumblebees (2) Camel Cricket (16) Dogbane Beetle (8)* Carpenter Ants (3) Field Cricket (3) Eyed Elater (2) Carpenter Bees (5) Grasshopper (20)** Fiery Searcher (1) Dauber (2) Longhorn Grasshopper (1) Glowworm (20)* Honeybees (9)*** Grapevine Beetle (10) Ichneumon Wasps (3) Phasmida Ground Beetle (4) Paper Wasps (4) Walking Stick (18) (all found on beauty berry) Ladybug (1) Velvet Ant (2) Longhorn Beetles (4) Plecoptera Milkweed Beetle (6) Isoptera Stoneflies (6) Rose Chafer (4) Termite Rove Beetle (2) Stag Beetle (2) Lepidoptera Other Arthropods: -

To Many, the Words Bug and Insect Are Interchangeable, and Refer to Those Six-Legged

by Tim McCabe and Eileen Stegemann Art by Jean Gawalt and Frank Herec What's the difference between a bug and an insect? o many, the words bug and insect are interchangeable, and refer to those six-legged creatures you see everywhere. However, in the scientific community, the two terms do have differentT meanings. The word bug refers to a specific subgroup of insects classified as "true bugs" which have a feeding tube instead of chewing mouthparts. Examples of true bugs are the shield and assassin bugs. So remember, all bugs may be insects, but not all insects are bugs. Banded Woolly Bear A member of the tiger moth only the queen overwintering (the rest die). family, the banded woolly bear is the lar- Bumblebees have relatively small wings when com- val stage of the Isabella moth. It gets pared to their large bodies, making one wonder at its name from its woolly, bristly, their ability to fly. To overcome this, the wings move in black and rust-colored coat. It eats a complicated figure-eight pattern that provides more low-growing vegetation. A familiar late summer and lift because of re-used airflow. fall sight, the woolly bear is thought by many to be Praying Mantis Appropriately named, the praying able to predict the severity of the upcoming winter mantis is a formidable predator that based on the width of its black bands. However, the holds its powerful front legs upraised real determining factors for band size are genetics and in a seemingly praying position while it environmental impacts experienced by the caterpillar waits to ambush its prey of insects such as past weather, crowding factors, and ingestion and spiders. -

Conclusions from Three Feeding Studies on Two Mantid Species, Popa Spurca and Tenodera Aridifolia

CONCLUSIONS FROM THREE FEEDING STUDIES ON TWO MANTID SPECIES, POPA SPURCA AND TENODERA ARIDIFOLIA Merande McCandless Keeper-Invertebrates, Saint Louis Zoo One Government Drive, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Three similar studies conducted on the African twig mantis Popa spurca and Chinese Mantis Tenodera aridifolia explored the effects of food quantity and feeding frequency on development, longevity, and fecundity of the two species. All three studies suggest that feeding mantids more and/or more often in all stages of development and maturity results in increased viability as measured by ootheca production, life span, and rate of survival to physical maturity. INTRODUCTION It is generally accepted that over-fed animals experience decreased bodily function and life expectancy due to obesity, but there are notable exceptions. A 1956 study by Odum and Connell, as well as a 1965 study by King and Farmer, demonstrated that migratory songbirds— who benefit from large energy stores—deposit fat outside of the heart, even at peak obesity (as cited in Gill, 1995, p. 297). Unsubstantiated rumors in the invertebrate field suggest that captive tarantulas and scorpions suffer decreased life expectancy from over-feeding, but no information—rumor or otherwise—indicate whether mantids are an exception or the rule. Where illness is concerned, short-lived animals who are afflicted often appear healthy, becoming deceased prior to exhibiting symptoms; the same could be true of obesity and its effects in short- lived invertebrates. Or, like some migratory bird species, mantids may actually benefit from additional food. If mantids are the rule and suffer ill effects from extreme feeding (too much or too little), a bell curve can be expected in areas such as life expectancy or fecundity—these areas peaking with optimal feeding and decreasing gradually as food is either increased or decreased from that amount. -

Praying Mantids Gary Watkins and Ric Bessin, Student and Extension Specialist Entfact-0418

Praying Mantids Gary Watkins and Ric Bessin, Student and Extension Specialist Entfact-0418 Although many refer to a member of this group as a ‘praying mantis,' mantis refers to the genus Mantis. Only some praying mantids belong to the genus Mantis. Mantid refers to the entire group. Mantids are very efficient and deadly predators that capture and eat a wide variety of insects and other small prey. They have a "neck" that allows the head to rotate 180 degrees while waiting for a meal to wander by. Camouflage coloration allows mantids to blend in with the background as they sit on twigs and stems waiting to ambush prey. The two front legs of the mantids are highly Figure 2. male Carolina preying mantis. specialized. When hunting mantids assume a "praying" position, folding the legs under their head. The pale green European mantid is intermediate in They use the front legs to strike out and capture their size, about 3 inches in length. The large (3 to 5 prey. Long sharp spines on the upper insides of these inches long) Chinese mantid is green and light legs allow them to hold to on their prey. The impaled brown. The Carolina mantid is a native insect. The prey is held firmly in place while being eaten. The European and Chinese species were introduced in spines fit into a groove on the lower parts of the leg the northeast about 75 years ago as garden predators when not in use. in hopes of controlling the native insect pest populations. There are three species of mantids in Kentucky, the European mantid (Mantis religiosa), Carolina mantid (Stagmomantis carolina), and Chinese Mantid (Tenodera aridifolia sinensis). -

PRAYING MANTIS by Lisa Marie Gee

DECEMBER 2019 WNY GARDENING MATTERS ARTICLE 127 PRAYING MANTIS by Lisa Marie Gee A praying mantis is a predator insect that feasts on live insects The adult mantis may be preyed upon by birds and primates. including moths, mosquitos, roaches, flies and aphids. It can also The European mantis is green, tan or dark brown in color. The eat small rodents, frogs, snakes and birds. Mantids are the only wings extend past the end of their abdomen. Males and females predator to feed on moths at night! They do not discriminate can fly but once the female’s eggs begin to develop, they become between “good and bad “ insects. Thus they are not always a too heavy to fly. The inside of the upper forearm will have a black beneficial predator. Praying mantises don’t bite humans but the spot which could or could not have a white spot within it. They leg spikes are sharp! live on foliage and inhabit gardens, hedgerows, meadows and Size depends on the species and age of the mantis (up to a year). roadsides. They are originally from Europe. The nymphs appear in The long spiked forelegs aid in catching prey.They are also used late May and mature around early-mid August. If the adults feel for grooming. The head is triangular in shape. It can be rotated threatened, they will expose the black spots on the inside of their almost 300 degrees. Praying mantises are masters at camouflage forearms and raise their wings. which is a great aid in hunting.. Females lay their eggs in a The Carolina mantis is native to North and South Carolina but is protective egg sac called an “ootheca” laid in late September and common in most of the U.S.