Managing Washington's Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulations Governing the Public Use of Washington State Parks

PARK RULES Regulations Governing the Public Use of Washington State Parks Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission NOTE: Regulations are subject to change. Contact park staff if you have questions. P&R 45-30100-54 (10/13) Table of Contents Page Chapter 352-32 WAC Public Use of State Park Areas (08/13/2013) .......................................................................................... 1 Chapter 352-12 WAC Moorage and Use of Marine and Inland Water Facilities (11/20/2008) ........................................................................................ 25 Chapter 352-20 WAC Use of Motor Driven Vehicles in State Parks–Parking Restrictions–Violations (11/30/2005) ........................................................................................ 27 Commission Policy/Procedure 65-13-1 Use of Other Power-Driven Mobility Devices by Persons with Disabilities at State Park Facilities (10/22/2013) ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 352-37 WAC Ocean Beaches (08/13/2013) ........................................................................................ 39 i Chapter 352-32 Chapter 352-32 WAC PUBLIC USE OF STATE PARK AREAS WAC DISPOSITION OF SECTIONS FORMERLY 352-32-010 Definitions. CODIFIED IN THIS CHAPTER 352-32-01001 Feeding wildlife. 352-32-011 Dress standards. 352-32-020 Police powers granted to certain employees. [Order 35, § 352-32-020, filed 7/29/77; Order 9, § 352-32-020, 352-32-030 Camping. filed 11/24/70.] Repealed by WSR 82-07-076 (Order 352-32-037 Environmental learning centers (ELCs). 56), filed 3/23/82. Statutory Authority: RCW 43.51.040. 352-32-040 Picnicking. 352-32-035 Campsite reservation. [Statutory Authority: RCW 352-32-045 Reservations for use of designated group facilities. 43.51.040(2). WSR 95-14-004, § 352-32-035, filed 352-32-047 Special recreation event permit. -

Washington Coastal Geodetic Control Network: Report and Station Index

Washington Coastal Geodetic Control Network: Report and Station Index Developed in Support of the Southwest Washington Coastal Erosion Study October 1999 Department of Ecology Publication #99-103 Richard C. Daniels1, Peter Ruggiero1, and Leonard E. Weber, LS2 1Washington Department of Ecology Shorelands & Environmental Assistance Program Coastal Monitoring & Analysis Program Olympia, WA 98504-7600 (360) 407-6000 2Weber GPS 5509 44th Court SE Lacey, WA 98503 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES......................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................vii SECTION 1: THE WASHINGTON COASTAL GEODETIC CONTROL PROJECT................. 1 1. Background Information ................................................................................................. 1 2. Existing Vertical and Horizontal Control........................................................................ 3 3. Network Design and Implementation ............................................................................. 4 3.1 Site Reconnaissance.......................................................................................... 4 3.2 Preliminary Field Operations ............................................................................ 5 3.3 Survey Operations............................................................................................. 9 3.4 Adjustment -

September Migration in the Pacific Northwest September 17–25, 2017

WASHINGTON: SEPTEMBER MIGRATION IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST SEPTEMBER 17–25, 2017 LEADER: BOB SUNDSTROM LIST COMPILED BY: BOB SUNDSTROM VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM WASHINGTON: SEPTEMBER MIGRATION IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST September 17–25, 2017 By Bob Sundstrom The rush of migration in September concentrates birds along Washington and southern British Columbia’s mountain ridges, coastal shorelines, and over the ocean itself. The September Migration in the Pacific Northwest tour takes full advantage of nature’s timing to showcase shorebirds, seabirds, and songbirds in the midst of southward migration. It seemed like each species we encountered had a unique story to tell: seabirds headed south to such different destinations as Antarctica, New Zealand, and Chile. Shorebirds passing through en route to Central and South America, as well as shorebirds arriving to winter in the Northwest. Post- breeding migrants that had just come north—pelicans, gulls, cormorants—arriving from Baja and places south along the Pacific Coast to reach food-rich waters of the Northwest. And loons and scoters coming south from nesting on tundra ponds across the Arctic, as Fox and Golden-crowned sparrows also arrived from northern breeding areas. The 2017 tour enjoyed superb weather, an admirable list of birds, a wonderfully congenial group, plus great food and a memorable journey through the scenic Northwest. We birded from Seattle to the Pacific Coast and then north along the Olympic Peninsula before crossing to Whidbey Island and then on to British Columbia—a loop that ran all the way from Willapa Bay in southwest Washington to Boundary Bay in southeast British Columbia. -

Regulations Governing the Public Use of Washington State Parks

PARK RULES Regulations Governing the Public Use of Washington State Parks Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission Table of Contents Page Chapter 352-32 WAC Public Use of State Park Areas (04/20/2016) .......................................................................................... 1 Chapter 352-12 WAC Moorage and Use of Marine and Inland Water Facilities (11/20/2008) ........................................................................................ 26 Chapter 352-20 WAC Use of Motor Driven Vehicles in State Parks–Parking Restrictions–Violations (11/30/2005) ........................................................................................ 28 Commission Policy/Procedure 65-13-1 Use of Other Power-Driven Mobility Devices by Persons with Disabilities at State Park Facilities (Commission Action date: 8/8/2013) .................................................. 30 Chapter 352-37 WAC Ocean Beaches (06/24/2016) ........................................................................................ 40 Chapter 352-32 Chapter 352-32 WAC PUBLIC USE OF STATE PARK AREAS WAC DISPOSITION OF SECTIONS FORMERLY 352-32-010 Definitions. CODIFIED IN THIS CHAPTER 352-32-01001 Feeding wildlife. 352-32-011 Dress standards. 352-32-020 Police powers granted to certain employees. [Order 35, 352-32-030 Camping. § 352-32-020, filed 7/29/77; Order 9, § 352-32-020, 352-32-037 Environmental learning centers (ELCs). filed 11/24/70.] Repealed by WSR 82-07-076 (Order 352-32-040 Picnicking. 56), filed 3/23/82. Statutory Authority: RCW 43.51.040. 352-32-045 Reservations for use of designated group facilities. 352-32-035 Campsite reservation. [Statutory Authority: RCW 352-32-047 Special recreation event permit. 43.51.040(2). WSR 95-14-004, § 352-32-035, filed 352-32-050 Park periods. 6/21/95, effective 7/22/95. Statutory Authority: RCW 352-32-053 Park capacities. -

Great Lakes Entomologist the Grea T Lakes E N Omo L O G Is T Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol

The Great Lakes Entomologist THE GREA Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol. 45, Nos. 3 & 4 Fall/Winter 2012 Volume 45 Nos. 3 & 4 ISSN 0090-0222 T LAKES Table of Contents THE Scholar, Teacher, and Mentor: A Tribute to Dr. J. E. McPherson ..............................................i E N GREAT LAKES Dr. J. E. McPherson, Educator and Researcher Extraordinaire: Biographical Sketch and T List of Publications OMO Thomas J. Henry ..................................................................................................111 J.E. McPherson – A Career of Exemplary Service and Contributions to the Entomological ENTOMOLOGIST Society of America L O George G. Kennedy .............................................................................................124 G Mcphersonarcys, a New Genus for Pentatoma aequalis Say (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) IS Donald B. Thomas ................................................................................................127 T The Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Missouri Robert W. Sites, Kristin B. Simpson, and Diane L. Wood ............................................134 Tymbal Morphology and Co-occurrence of Spartina Sap-feeding Insects (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha) Stephen W. Wilson ...............................................................................................164 Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Scutelleridae) Associated with the Dioecious Shrub Florida Rosemary, Ceratiola ericoides (Ericaceae) A. G. Wheeler, Jr. .................................................................................................183 -

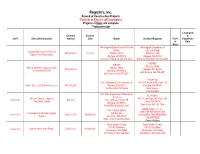

Projects *Projects in Red Are Still in Progress Projects in Black Are Complete **Subcontractor

Rognlin’s, Inc. Record of Construction Projects *Projects in Red are still in progress Projects in black are complete **Subcontractor % Complete Contract Contract & Job # Description/Location Amount Date Owner Architect/Engineer Class Completion of Date Work Washington Department of Fish and Washington Department of Wildlife Fish and Wildlife Log Jam Materials for East Fork $799,000.00 01/11/21 PO Box 43135 PO Box 43135 Satsop River Restoration Olympia, WA 98504 Olympia, WA 98504 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 WSDOT WSDOT PO Box 47360 SR 8 & SR 507 Thurston County PO Box 47360 $799,000.00 Olympia, WA 98504 Stormwater Retrofit Olympia, WA 98504 John Romero 360.570.6571 John Romero 360.570.6571 Parametrix City of Olympia 601 4th Avennue E. 1019 39th Avenue SE, Suite 100 Water Street Lift Station Generator $353,952.76 Olympia, WA 98501 Puyallup, WA 98374 Jim Rioux 360-507-6566 Kevin House 253.604.6600 WA State Department of Enterprise SCJ Alliance Services 14th Ave Tunnel – Improve 8730 Tallon Lane NE, Suite 200 20-80-167 $85,000 1500 Jefferson Street SE Pedestrian Safety Lacey, WA 98516 Olympia, WA 98501 Ross Jarvis 360-352-1465 Bob Willyerd 360.407.8497 ABAM Engineers, Inc. Port of Grays Harbor 33301 9th Ave S Suite 300 Terminals 3 & 4 Fender System PO Box 660 20-10-143 $395,118.79 12/08/2020 Federal Way, WA 98003-2600 Repair Aberdeen, WA 98520 (206) 357-5600 Mike Johnson 360.533.9528 Robert Wallace Grays Harbor County Grays Harbor County 100 W. -

1968 Mountaineer Outings

The Mountaineer The Mountaineer 1969 Cover Photo: Mount Shuksan, near north boundary North Cascades National Park-Lee Mann Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during June by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111. Clubroom is at 7191h Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. EDITORIAL STAFF: Alice Thorn, editor; Loretta Slat er, Betty Manning. Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, at above address, before Novem ber 1, 1969, for consideration. Photographs should be black and white glossy prints, 5x7, with caption and photographer's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double-spaced and include writer's name, address and phone number. foreword Since the North Cascades National Park was indubi tably the event of this past year, this issue of The Mountaineer attempts to record aspects of that event. Many other magazines and groups have celebrated by now, of course, but hopefully we have managed to avoid total redundancy. Probably there will be few outward signs of the new management in the park this summer. A great deal of thinking and planning is in progress as the Park Serv ice shapes its policies and plans developments. The North Cross-State highway, while accessible by four wheel vehicle, is by no means fully open to the public yet. So, visitors and hikers are unlikely to "see" the changeover to park status right away. But the first articles in this annual reveal both the thinking and work which led to the park, and the think ing which must now be done about how the park is to be used. -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

North Cascades National Park I Mcallister Cutthroat Pass A

To Hope, B.C. S ka 40mi 64km gi t R iv er Chilliwack S il Lake v e CHILLIWACK LAKE SKAGIT VALLEY r MANNING - S k a g PROVINCIAL PARK PROVINCIAL PARK i PROVINCIAL PARK t Ross Lake R o a d British Columbia CANADA Washington Hozomeen UNITED STATES S i Hozomeen Mountain le Silver Mount Winthrop s Sil Hoz 8066ft ia ve o Castle Peak 7850ft Lake r m 2459m Cr 8306ft 2393m ee e k e 2532m MOUNT BAKER WILDERNESS Little Jackass n C Mount Spickard re Mountain T B 8979ft r e l e a k i ar R 4387ft Hozomeen Castle Pass 2737m i a e d l r C ou 1337m T r b Lake e t G e k Mount Redoubt lacie 4-wheel-drive k r W c 8969ft conditions east Jack i Ridley Lake Twin a l of this point 2734m P lo w er Point i ry w k Lakes l Joker Mountain e l L re i C ak 7603ft n h e l r C R Tra ee i C i Copper Mountain a e re O l Willow 2317m t r v e le n 7142ft T i R k t F a e S k s o w R Lake a 2177m In d S e r u e o C k h g d e u c r Goat Mountain d i b u i a Hopkins t C h 6890ft R k n c Skagit Peak Pass C 2100m a C rail Desolation Peak w r r T 6800ft li Cre e ave 6102ft er il ek e e Be 2073m 542 p h k Littl 1860m p C o Noo R C ks i n a Silver Fir v k latio k ck c e ee Deso e Ro Cree k r Cr k k l e il e i r B e N a r Trail a C To Glacier r r O T r C Thre O u s T e Fool B (U.S. -

North Cascades National Park Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Business Management Group North Cascades National Park 2012 Business Plan Produced by Sunrise at Copper Lookout. National Park Service Business Management Group Table of Contents U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spring 2012 2 INTRODUCTION National Park Business Plan Process 2 Letter from the Superintendent 3 Introduction to North Cascades National Park The purpose of business planning in the National Park Service (NPS) is to improve the ability of parks to more clearly 4 PARK OVERVIEW communicate their financial and operational status to principal 4 Orientation stakeholders. A business plan answers such questions as: What 5 Mission and Foundation is the business of this park unit? What are its priorities over 6 Resources the next five years? How will the park allocate its resources to 7 Visitor Information achieve these goals? 8 Personnel 9 Volunteers The business planning process is undertaken to accomplish three 10 Partnerships main tasks. First, it presents a clear, detailed picture of the state 12 Strategic Goals of park operations and priorities. Second, it outlines the park’s 14 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW financial projections and specific strategies the park may employ to marshal additional resources to apply toward its operational 14 Funding Sources and Expenditures needs. Finally, it provides the park with a synopsis of its funding 15 Division Allocations sources and expenditures. 16 DIVISION OVERVIEWS 16 Facility Management 18 Resource Management -

Twenty-Ninth Update of the Federal Agency Hazardous Waste Compliance Docket

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 03/03/2016 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2016-04692, and on FDsys.gov 6560-50-P ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY [FRL- 9943-17-OLEM] Twenty-Ninth Update of the Federal Agency Hazardous Waste Compliance Docket AGENCY: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: Since 1988, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has maintained a Federal Agency Hazardous Waste Compliance Docket (“Docket”) under Section 120(c) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). Section 120(c) requires EPA to establish a Docket that contains certain information reported to EPA by Federal facilities that manage hazardous waste or from which a reportable quantity of hazardous substances has been released. As explained further below, the Docket is used to identify Federal facilities that should be evaluated to determine if they pose a threat to public health or welfare and the environment and to provide a mechanism to make this information available to the public. This notice includes the complete list of Federal facilities on the Docket and also identifies Federal facilities reported to EPA since the last update of the Docket on August17, 2015. In addition to the list of additions to the Docket, this notice includes a section with revisions of the previous Docket list. Thus, the revisions in this update include 7 additions, 22 corrections, and 42 deletions to the Docket since the previous update. At the time of publication of this notice, the new total number of Federal facilities listed on the Docket is 2,326. -

Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report

Don Hoch Direc tor STATE O F WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSI ON 1111 Israel Ro ad S.W. P.O . Box 42650 Olympia, WA 98504-2650 (360) 902-8500 TDD Telecommunications De vice for the De af: 800-833 -6388 www.parks.s tate.wa.us March 22, 2018 Item E-5: Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This item reports to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission the current status of the process to rename the Iron Horse State Park Trail (which includes the John Wayne Pioneer Trail) and a verbal update on recent trail management activities. This item advances the Commission’s strategic goal: “Provide recreation, cultural, and interpretive opportunities people will want.” SIGNIFICANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Initial acquisition of Iron Horse State Park Trail by the State of Washington occurred in 1981. While supported by many, the sale of the former rail line was controversial for adjacent property owners, some of whom felt that the rail line should have reverted back to adjacent land owners. This concern, first expressed at initial purchase of the trail, continues to influence trail operation today. The trail is located south of, and runs roughly parallel to I-90 (see Appendix 1). The 285-mile linear property extends from North Bend, at its western terminus, to the Town of Tekoa, on the Washington-Idaho border to the east. The property consists of former railroad corridor, the width of which varies between 100 feet and 300 feet. The trail tread itself is typically 8 to 12 feet wide and has been developed on the rail bed, trestles, and tunnels of the old Chicago Milwaukee & St.