In the Film Kong Lear, There Is a Relatively Long And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: a New York City Story Online

ZmKzi [Read download] Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story Online [ZmKzi.ebook] Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story Pdf Free Kris Needs audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1025856 in eBooks 2015-10-12 2015-10-18File Name: B0100QGEGW | File size: 56.Mb Kris Needs : Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Nice overview of New York City when it was a ...By John J. PotterNice overview of New York City when it was a dangerous creative cauldron of activity. Furthermore, Harrry Hill supplies insightful writing that adds resonance to Suicide's musical contributions to the period and the history of electronic music. BUY their first album and this tome!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A history of New York's musical art world in the 70'sBy Timm DavisonA great read0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. True originals. True story.By CustomerFantastic. ldquo;We were living through the realities of war and bringing the war onto the stage... Everybody hated us, manrdquo; Alan Vega Born out of the city's vibrant artistic underground as a counter-cultural performance art statement, opposing the war by mirroring its turmoil, Suicide became the most terrifyingly iconoclastic band in history, and also one of the most influential. -

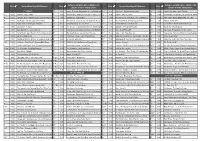

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

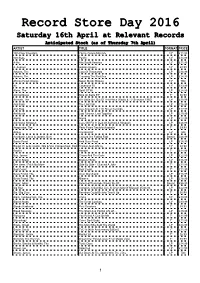

Record Store Day 2016

Record Store Day 2016 Saturday 16th April at Relevant Records Anticipated Stock (as of Thursday 7th April) ARTIST TITLE FORMAT PRICE 13th Floor Elevators You're Gonna Miss Me 10" £11.99 808 State Pacific 12" £14.99 A-Ha Hits South America 12" £11.99 A. Avenue Golden Queen 12" £8.99 Adverts, The Cast Of Thousands LP £18.99 Adverts, The Crossing The Red Sea LP £24.99 African Head Charge Super Mystic Brakes 10" TBC Air Casanova 70 12" £13.99 Alarm, The Spirit Of '86 LP £24.99 Animal Noise Sink Or Swim EP 7" £6.99 Animals, The We Gotta Get Out Of This Place (Radio & TV Sessions 1965) LP £18.99 Anti Pasti The Last Call LP £16.99 Anti-Flag Live Acoustic At 11th Street Records LP £17.99 Architects Lost Forever, Lost Together LP £19.99 Arena Arena LP £22.99 Ashford & Simpson Love Will Fix It: Best Of Ashford & Simpson LP £26.99 Associates, The Party Fears Two b/w Australia 7" £9.99 Atreyu The Best Of LP TBC Auerbach, Loren & Jansch, Bert Colours Are Fading Fast Boxset £48.99 Bardo Pond Acid Guru Pond LP £26.99 Bargel, R. & de Caster, Nils & Van Campenhout, Rola Frankie And Johnny 10" £8.99 Bastille Hangin' 7" £11.99 Bay, James Chaos And The Calm LP £22.99 Beach Slang Broken Thrills 12" £16.99 Bee Gees / Faith No More Side By Side - I Started A Joke 7" £11.99 Best Coast Best Coast 7" £11.99 Bevis Frond, The Inner Marshland LP £18.99 Bevis Frond, The Miasma LP £18.99 Beyer, Adam Selected Drumcode Works 96 -00 Boxset £56.99 Big Star Complete Columbia: Live At University Of Missouri 25.04.93 LP £22.99 Bis / Big Zero Boredom Could Be b/w Tear It Up -

Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: a New York City Story Free Ebook

FREEDREAM BABY DREAM: SUICIDE: A NEW YORK CITY STORY EBOOK none | 304 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | OMNIBUS PRESS | 9781783057887 | English | London, United Kingdom You And All Your Closest Friends Need This Giant Moscow Mule Dream Baby Dream Suicide A New York City Story Author: Kris Needs ISBN: Genre: Music File Size: 43 MB Format: PDF, ePub, Mobi Download: Read: PHD Rooftop at Dream Downtown in New York City is serving up the most insane hot chocolate you'll ever see. It weighs 20 pounds, serves 22 people, and costs $! Delish editors handpick every product we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page. For you and 21 of your closest frie. Read our critical review of BBC2's Bradford: City of Dreams, a two part documentary exploring this troubled but vibrant northern city. London By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and consent to receive emails from Time Out about news, events, offers and par. Order Your Dream Pizza To Find Out Where In New York City You Should Live Extreme Makeover: Gigi Home Edition! Gigi Hadid flaunted her interior design skills when she gave fans a rare glimpse inside her New York City apartment. The model, 25 — who is expecting her first child with boyfriend, Zayn Malik — shared photos of her Bohemian-inspired home via Instagram on Saturday. Antiques and French-inspired decor fill style icon Iris Apfel’s exuberant three-bedroom Park Avenue apartment To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories. By Amanda Vail Photography by Roger Davies Our website, , offers constant original coverage of the interior. -

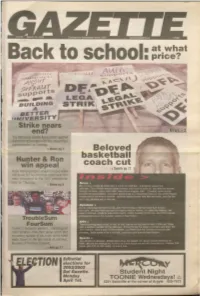

At What • Price?

• at what • price? Strike nears end? The Dalhousie Faculty Association reached a tentative agreement with the University's administration on Tuesday. >News pg 3 Beloved basket a I nter & Ron coach cut win appeal > Sports pg 12 Anna Hunter jumped up and cheered when she found out her and slate-mate Dave Ron were reinstated to the DSU presidential race on Thursday. N > ews pg 4 TroubleSum FourSum Sum41 's favourite pastime: snatching all hotel furniture from their guitar tech's and recreating replicas of his room in the hotel lobby (down to the last article of clothing). No piece of furniture is spared. >Arts pg 11 Editorial elections lor TION 2002/2003 Dal Gazette. Student Night Monday TOONIE Wednesdavs! cJ3er April 1st. 5221 Sackville at the corner of Argyle ~25-7673 Rll'avet CUTS eHGIU5iVe Wilh SUSAlJOtJ"f Dalhousie Student Hook any Husabout Consecutive Pass of at least 1month duration or a Union FleHipass of ab least 15 days in 2montihs + tiiiHusabouti London link between Loooon and Paris aoo geb af@IMmrtt11%1tWW41Mii • TWO NtGHTS AT ST. CHRISTOPHER'S INN • BIG BUS PASS • ONE. EVENING MEAL • DAILY BAGGED BREAKFAST • FREt. HOT TJB AND SAUNA USE >! Must; be boohed betirneen March 15 - Mag 91/02 ~ 0 ~ ::1RAVELCUIS Canada's student travel exoerts! WEDNESDAY NIGHTS OPEN MIC NIGHT 100 PRJZE EVER_Y WEEK THORSDAYS ARE The DSU would like to remind everyone that when the strike is over the DSU elections will continue with a shortened campaigning period and 3 days of voting. ENTER TO WIN! c.,.,., to t h< Grawood Lounge and fill out your ballot to WIN TICKETS TO THE SHOWI Tired of doing your taxes? Do them quickly ana easily online with QuickTaxWeb. -

Michele Mulazzani's Playlist: Le 999 Canzoni Piu' Belle Del XX Secolo

Michele Mulazzani’s Playlist: le 999 canzoni piu' belle del XX secolo (1900 – 1999) 001 - patti smith group - because the night - '78 002 - clash - london calling - '79 003 - rem - losing my religion - '91 004 - doors - light my fire - '67 005 - traffic - john barleycorn - '70 006 - beatles - lucy in the sky with diamonds - '67 007 - nirvana - smells like teen spirit - '91 008 - animals - house of the rising sun - '64 009 - byrds - mr tambourine man - '65 010 - joy division - love will tear us apart - '80 011 - crosby, stills & nash - suite: judy blue eyes - '69 012 - creedence clearwater revival - who'll stop the rain - '70 013 - gaye, marvin - what's going on - '71 014 - cocker, joe - with a little help from my friends - '69 015 - fleshtones - american beat - '84 016 - rolling stones - (i can't get no) satisfaction - '65 017 - joplin, janis - piece of my heart - '68 018 - red hot chili peppers - californication - '99 019 - bowie, david - heroes - '77 020 - led zeppelin - stairway to heaven - '71 021 - smiths - bigmouth strikes again - '86 022 - who - baba o'riley - '71 023 - xtc - making plans for nigel - '79 024 - lennon, john - imagine - '71 025 - dylan, bob - like a rolling stone - '65 026 - mamas and papas - california dreamin' - '65 027 - cure - charlotte sometimes - '81 028 - cranberries - zombie - '94 029 - morrison, van - astral weeks - '68 030 - springsteen, bruce - badlands - '78 031 - velvet underground & nico - sunday morning - '67 032 - modern lovers - roadrunner - '76 033 - talking heads - once in a lifetime - '80 034 -

Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: a New York City Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DREAM BABY DREAM: SUICIDE: A NEW YORK CITY STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK none | 304 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | OMNIBUS PRESS | 9781783057887 | English | London, United Kingdom Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story PDF Book Suicide by Suicide Musical group Recording 30 editions published between and in 4 languages and held by WorldCat member libraries worldwide. This item doesn't belong on this page. Dirty water : the birth of punk attitude Recording 1 edition published in in English and held by 10 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. Suicide by Suicide Musical group Recording 9 editions published between and in English and Undetermined and held by 14 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. Most widely held works about Suicide Musical group. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Publication Timeline. The needlepoint carpet is English. MyDomaine uses cookies to provide you with a great user experience. I also believe in always making an investment in staple pieces that can be versatile and withstand trends. New York Books. With tension-rod bookcases creating the perfect, easy-to-remove statement for a rental, the designer knew from the start that the bookcase would naturally become a focal point of the space. The MJ poster swiftly vetoed, Silber worked with her client to create a space that felt elegant and could entertaining large crowds yet still felt comfortable and easygoing. Mistress America : original motion picture soundtrack by Dean Wareham Recording 2 editions published in in English and held by 17 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. Step into the bachelor pad we'd all want to live in—this home is a lesson in comfort and practicality. -

Adele with Just a Couple of Cursory Listens to the Few Tracks That Popped

19 – Adele With just a couple of cursory listens to the few tracks that popped up all over the Internet through 2007, comparisons were made between Adele, the much-hyped brassy British songstress, and Amy Winehouse, the...much-hyped brassy British songstress. However, after a solid listen to 19, the first full sampling by the up-and-coming Adele, listeners are forced to throw all comparisons to the wind; Adele is simply too magical to compare her to anyone. Bluesy like it's no one's business yet voluptuously funky in a contemporary way, Adele rocks out 19 with a unique voice and gritty sound that dazzle endlessly. Synthesizing blues, jazz, folk, soul, and even electric pop, Adele mystifies through her mature songwriting skills and jaw-dropping arrangements. As the album opens with "Daydreamer," Adele's illusionary instrument -- over minimal sounds -- engulfs the listener with a gorgeous feeling of awe and wonderment. On "Melt My Heart to Stone" and the bona fide hit "Chasing Pavements," Adele allows herself to soar over the strings and power her way through these incredible songs. The upbeat "Right as Rain" is just wonderful, with clear Ashford & Simpson influences speckled all over it in an upbeat set. Nearly all the tracks seem to have been nurtured to glory over months as labors of love. What's simply awesome on 19 is its capability to capture the listener through mere teasing; Adele doesn't shout for attention, and doesn't rely on anyone but herself to prove she's worth it, in the same vein as Sara Bareilles, another heavily praised artist of 2007. -

Rock & Roll Is a State of Mind / Johnny Pierre

© 2019 Mind Smoke Records www.msmokemusic.com 01. A Little Rock & Roll 02. Devil’s Kiss 03. The Curious Stain 04. House of Women 05. Up All Night 06. One Big Street 07. Hash Tag Baby 08. Tool Shed Shangri-La 09. King of Pop 10. Busy World 11. Cemetery Moonlight 12. Rock & Roll is a State of Mind 13. Rock & Roll Coda © 2019 Mind Smoke Records All Songs © Mind Smoke Music SESSION CREDITS Johnny Pierre – Vocals, Guitars, Keyboards, Bass, Bass Synthesizer Ray Finch – Intro Guitar Riff (Track 1), Lead Guitar (Track 3) Chris James – 1st Guitar solo (Track 1), Lead Guitar (Track 7) Dave Filloramo – 2nd Guitar Solo (Track 1), Lead Guitar (Track 12) Jeff “Shadow Groove” Goldstein – Bass Guitar (Tracks 1, 3, 10, 12) Rusty Walker – Keyboards (Tracks 2,4, 6, 7, 8,) Jim Treutlein – Acoustic Guitar & Backing Vocal (Track 1) Rudy Schnee – Acoustic drums, Drum machine & Percussion Don Rentier – Bass Guitar (Track 4, 6, 7, 13) John “Buck” Green – Lead Guitar (Track 10) Alex Zander – Lead Guitar (Track 8) Produced by: The Mad Turk Recorded @ Mind Smoke Studios Nov. 2018– March 2019 George Reiger This album is dedicated to my dear friend George Reiger. I met George in my first year at the University of Dayton. George had a genuine rock & roll attitude which made a big impression on me. Over my years in college, George really influenced the way I felt about rock & roll. Thanks George! As a songwriter, I've always enjoyed writing in a wide variety of musical genres but the rock & roll genre has always been my favorite genre. -

Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Page 2 of 43

Page 1 of 43 **01 Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Page 2 of 43 **01 Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Artist Name 1415 songs, 2.6 days, 5.59 GB Alvin Robinson Something You Got Alvin Robinson Let Me Down Easy Artist Name Alvin Robinson Baby Don't You Do It A.C. Reed Talkin' About My Friends Alvin Robinson Something You Got Aarch Hall Jr. Konga Joe Alvin Robinson Let The Good Times Roll Aarch Hall Jr. Monkey In My Hat Band American Spring Fallin' In Love The Abstracts Smell of Incense Amos Milburn Jr. Gloria The Ad Libs Kicked Around Andre Williams Humpin', Bumpin' and Thumping The African Beavers Find My Baby Andre Williams Sweet Little Pussycat The African Beavers You Got Something Andre Williams Just Because of a Kiss The African Beavers Night Time Is the Right Time Andre Williams Bacon Fat The African Beavers Jungle Fever Andre Williams (Mr. Rhythm) with Vocal Group Mean Jean Al Casey and the K-C-Ettes What Are We Gonna Do In '64? Andre Williams with the Don Juans Going Down to Tia Juana Al Casey with the K-C-Ettes Surfin' Hootenanny Angel Down We Go (From The Orig. Soundtrack Of The A.… Angel, Angel Down We Go Al Davis Go Baby Go Angie Caroll Sleep Little Children Al Ferrier Yard Dog Angie Caroll Ah Baby, That's Nice Al Green Sweet As Love, Strong As Death Ann Sexton Have a Little Mercy Al Green I'm Glad You're Mine Ann-Margret It's a Nice World To Visit (But Not To Live In) Al Perkins Need To Belong Apollos That's the Breaks Al Quick and The Masochists Theme From The Sadistic Hypnotist The Arbors Touch Me Al Terry Watch Dog Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead Alan Pierce Swampwater Aretha Franklin I Can't Wait Until I See My Baby's Face Alan Vega Jukebox Babe Arondies 69 Albert Collins Conversation With Collins Arthur Ponder Dr. -

Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: a New York City Story Free

FREE DREAM BABY DREAM: SUICIDE: A NEW YORK CITY STORY PDF none | 304 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | OMNIBUS PRESS | 9781783057887 | English | London, United Kingdom Hometown Babies: New York City, New York | Parents Guerin; the screen is also French, while the chair at left, covered in an Old World Weavers tapestry fabric, is 17th-century Sicilian. In the entry, an 18th-century English gilt chinoiserie mirror and an Italian console. An Italian tole chandelier above a Maison Jansen table draped in a woven paisley throw. The first painting Apfel ever bought—a portrait of the Infanta Margarita she picked up 60 years ago at an antiques shop in Florence. Bakelite jewelry in the paws of a hand-carved Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story mountain dog. The entry contains an 18th-century French screen leftan earlyth-century painted Genoese corner cabinet, and Louis XVI—style chairs upholstered in an Old World Weavers cut velvet. The needlepoint carpet is English. Racks of her vintage pieces fill a spare room; she is especially fond of the metallic-check coat by Galanos. A hallway is lined with dog paintings and 19th-century English bookcases brimming with volumes on fashion, decorative arts, and Chinese costumes and textiles. Explore Celebrity Homes contributor:Robert Rufino. Suicide (Musical group) [WorldCat Identities] The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. -

Suffering from Realness Suffering from Realness

SUFFERING FROM REALNESS SUFFERING FROM REALNESS Denise Markonish “Our world is strange and often fake and corrupt. But we think it’s normal because we can’t see anything else.” —Adam Curtis, HyperNormalisation (2016) REALNESS in the 21st century is increasingly artists working in the United States examining complicated. In 2016, British filmmaker Adam the human condition from all sides, creating Curtis directed HyperNormalisation, which works that are both personal and universal, traces society’s descent into—to borrow addressing racism, violence, gender equality, Stephen Colbert’s term—‘truthiness’ and the the politicized body of wartime, the anxious systematic confusion it has created, from the body, the complexity of responsibility, and Reagan through Trump administrations. The the future. Writer Elaine Scarry says, “It will film outlines how, since the 1970s, corporations gradually become apparent that at particular and politicians have gained power over the moments when there is within a society a crisis “real world” by creating a “fake world” that they of belief…the sheer material factualness of stabilize and control. Examples range from the human body will be borrowed to lend that various financial crises to the use of Libyan cultural construct the aura of ‘realness’ and dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi as a public ‘certainty.’ (The Body in Pain: The Making and relations pawn. In the last two years, as Donald Unmaking of the World, 1985). Working in all Trump’s administration took office, the media, the artists in Suffering from Realness absurdity has amplified as xenophobic behavior rouse us from the hyper-normal, helping us has reached new extremes.