Read Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Agri-Environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England

Case Study 3 Implications of Agri-environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England This case study demonstrates the implications of agri-environmental schemes in the Lake District National Park. This farm is subject of an ESA (Environmentally Sensitive Area) agreement. The farm lies at the South Eastern end of Buttermere lake in the Cumbrian Mountains. This is a very hard fell farm in the heart of rough fell country, with sheer rock face and scree slopes and much inaccessible land. The family has farmed this farm since 1932 when the present farmer’s grandfather took the farm, along with its hefted Herdwick flock, as a tenant. The farm was bought, complete with the sheep in 1963. The bloodlines of the present flock have been hefted here for as long as anyone can remember. A hard fell farm The farmstead lies at around 100m above sea level with fell land rising to over 800m. There are 20ha (50 acres) of in-bye land on the farm, and another 25ha (62 acres) a few miles away. The rest of the farm is harsh rough grazing including 365ha (900 acres) of intake and 1944ha (4,800acres) of open fell. The farm now runs two and a half thousand sheep including both Swaledales and Herdwicks. The farmer states that the Herdwicks are tougher than the Swaledales, producing three crops of lambs to the Swaledale’s two. At present there are 800 ewes out on the fell. Ewes are not tupped until their third year. Case Study 3 Due to the ESA stocking restriction ewe hoggs and gimmer shearlings are sent away to grass keep for their first two winters, from 1 st November to 1 st April. -

Mervyn Edwards

SHEEP FARMING ON THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS ADAPTING TO CHANGE Mervyn Edwards 1 Contents page Forward 3 1. Lake District high fells – brief description of the main features 4 2. Sheep farming – brief history 4 3. Traditional fell sheep farming 5 4. Commons 8 5. A way of life 9 6. Foot and Mouth disease outbreak 2011 11 7. Government policy and support 11 8. Fell sheep farming economy 14 9. Technical developments 16 10. The National Trust 18 11. The National Park Authority 18 12. Forestry and woodland 19 13. Sites of Specially Scientific Interest 20 14. Government agri-environment schemes 21 15. Hefted flocks on the Lake District commons and fells – project Report June 2017 24 16. World Heritage Site 25 17. Concluding thoughts 27 Acknowledgements 30 My background 31 Updated and revised during 2017 Front cover picture showing Glen Wilkinson, Tilberthwaite gathering Herdwick sheep on the fell. Copyright Lancashire Life. 2 Forward These notes are my thoughts on fell sheep farming in the Lake District written following my retirement in 2014, perhaps a therapeutic exercise reflecting on many happy years of working as a ‘Ministry’ (of Agriculture) adviser with sheep farmers. Basically, I am concerned for the future of traditional fell sheep farming because a number of factors are working together to undermine the farming system and way of life. Perhaps time will reveal that my concern was unfounded because the hill farming sector has been able to withstand changes over hundreds of years. I have no doubt that the in-bye and most of the intakes will always be farmed but what will happen on the high fells? Will there be a sufficient number of farmers willing and able to shepherd these areas to maintain the practice of traditional fell sheep farming? Does it matter? 3 1. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

Hefted Flocks on the Lake District Commons and Fells

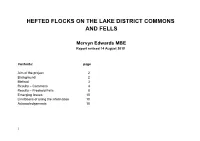

HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Contents: page Aim of the project 2 Background 2 Method 3 Results – Commons 4 Results – Freehold Fells 8 Emerging Issues 10 Limitations of using the information 10 Acknowledgements 10 1 HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Aim of the project The aim was to strengthen the knowledge of sheep grazing practices on the Lake District fells. The report is complementary to a series of maps which indicate the approximate location of all the hefted flocks grazing the fells during the summer of 2016. The information was obtained by interviewing a sample of graziers in order to illustrate the practice of hefting, not necessarily to produce a strictly accurate record. Background The basis for grazing sheep on unenclosed mountain and moorland in the British Isles is the practice of hefting. This uses the homing and herding instincts of mountain sheep making it possible for individual flocks of sheep owned by different farmers to graze ‘open’ fells with no physical barriers between these flocks. Shepherds have used this as custom and practice for centuries. Hefted sheep, or heafed sheep as known in the Lake District, have a tendency to stay together in the same group and on the same local area of land (the heft or heaf) throughout their lives. These traits are passed down from the ewe to her lambs when grazing the fells – in essence the ewes show their lambs where to graze. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

Breeding Ewes, Shearlings & Gimmer Lambs

5500 SWALEDALE, ROUGH FELL, Cheviot, Herdwick & Scottish Blackface Breeding Ewes, Shearlings & Gimmer Lambs Friday 27th September 2019 Sale to commence 10am at J36 Rural Auction Centre North West Auctions. J36 Rural Auction Centre, Crooklands, Milnthorpe, Cumbria, LA7 7FP t. 015395 66200 f. 015395 66211 www. nwauctions.co.uk e. [email protected] Sale Conditions Stock will be sold under the conditions of sale displayed in the Mart, recommended by the Livestock Auctioneers’ Association for England and Wales. Purchasers please bring the CPH number, address & postcode of the premises where the animals will be moved to and the registration number of the vehicle in which they are to be transported. These are all required when printing the movement licences. The Auctioneers & Fieldsmen will be pleased to assist in arranging transport for livestock. Vendors please make sure all sheep are correctly tagged before coming to Market. All breeding sheep are to be treated against scab and accompanied to the Market with a signed Sheep Scab Declaration form. Payment Payment on the day is required unless alternative arrangements have been made in advance Payment by Cheque for established customers or Debit Card Our bank account details for customers wishing to pay by Online Banking Transaction Bank: Lloyds Sort Code: 30 -16 -28 Account Number: 22425168 Please include your account number GDPR The information provided on these forms will be used by North West Auctions to keep in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. We only share this information with other members of our group and if you do not want to be contacted for marketing purposes please notify us in writing. -

Scientists Shine Spotlight on Herdwick Sheep Origins -- Sciencedaily

1/31/2014 Scientists shine spotlight on Herdwick sheep origins -- ScienceDaily Scientists shine spotlight on Herdwick sheep origins Date: January 29, 2014 Source: University of York A new study highlights surprising differences between Herdwick sheep and their closest neighbouring UK upland breeds. The research, led by The Sheep Trust, a national charity based at the University of York, is the first of its kind to compare the genetics of three commercially farmed breeds all concentrated in the same geographical region of the UK. Scientists worked with hill farmers to explore the genetic structures of Herdwicks, Rough Fells and Dalesbred, breeds locally adapted to the harsh conditions of mountains and moorlands. A Herwick Sheep. Local Cumbrian folklore speaks of connections between the The study, published in PLOS Herdwicks and Viking settlers. The coming together of the genetic evidence with ONE, discovered that historical evidence of Viking raiders and traders in the Wadden islands and Herdwicks contained features adjacent coastal regions, suggests the folklore is right but extends the connection of a 'primitive genome', found to Rough Fells. previously in very few breeds worldwide and none that have Credit: University of York been studied in the UK mainland. The data suggest that Herdwicks may originate from a common ancestral founder flock to breeds currently living in Sweden and Finland, and the northern islands of Orkney and Iceland. Herdwicks and Rough Fell sheep both showed rare genetic evidence of a historical link to the ancestral population of sheep on Texel, one of the islands in the Wadden Sea Region of northern Europe and Scandinavia. -

A Note from the Chairman

Whitefaced Woodland Sheep Society Web site: www.whitefacedwoodland.co.uk Newsletter 74 - Spring 2011 Chairman’s View Shows and Sales in 2011 Not much to report in this edition as we emerge The shows listed all offer specific Woodland from what has seemed like a winter without end. classes – now including Ryedale Show in July. Forage prices have been and remain horrifically high for those of us without much grazing since 11 June – Honley Show, Honley, West Yorks. the snows arrived in November but with hogg Contact: Paul Sykes 01484 680731. prices also nicely high, the profit is not entirely Judge: Tessa Wigham disappearing into the feed rack. I suppose a 40% drop in ewe numbers in the national flock since 19 June – Harden Moss Sheep Show and 2004 has something to do with high values Sheepdog Trials, Holmfirth. Contact: Christine (horned hoggs this week at Bakewell 180p per Smith 01484 680823. Judge: Karen Dowey l/w kilo) together with a high export demand supported by the exchange rate. 29-30 June - Royal Norfolk Show, Norwich. Judge: Jeff Dowey. Schedule from Philip Onions has provided us in this edition with [email protected] or phone 01603 another of his flock profiles, this time moving on 731965. www.royalnorfolkshow.co.uk to the Doweys at Pikenaze at Woodhead – as close to Woodland heartland as you can get and a 12-14 July – Great Yorkshire Show, Harrogate. very strong heart it is as well. Thanks again Contact: Amanda West on 01423 546231 or Philip for yet another piece of your excellent [email protected]. -

Rare Breed Catalogue 28Th April 2.Pub

Sale of Rare & Minority Breed Livestock In association with RBST Photo curtesy of the Westmorland Flock Saturday 28 th April 2018 Sale to commence at 11am Sale Conditions Stock will be sold under the conditions of sale displayed in the mart, recommended by the Livestock Auctioneers’ Association for England and Wales. All heifers offered for sale are not warranted as breeders unless otherwise stated. Please note that ear numbers for all cattle must be given to the auctioneers on the re- spective entry forms supplied. All unentered cattle and those missing their turn in the ballot will be offered for sale at the end of the catalogued entries. No lots can leave the market without a ‘pass slip’ being issued by the main office Purchasers have two working days from time of sale to satisfy themselves that all docu- mentation received is correct and any discrepancies must be notified to the auctioneers within that time limit. Paperwork must accompany livestock and if making multiple loads please make sure that the paperwork is presented with the first load. TB Status Notification If you are a 1 year TB test holding, please ensure your cattle have been tested within the 60 days prior to sale date. Please bring a copy of your current TB Test Certificate with your passports and indicate on the blue entry form how many days remain on your current test. The information given is for guidance purposes only. Vendors: please ensure all cattle have two ministry approved ear tags. Please make sure you have your stock forward as early as possible to ensure your stock is lotted and penned as swiftly as possible. -

Rare, Endangered & Vulnerable Breeds Of

Rare, endangered & vulnerable breeds of emphasizing the wool-growing kinds Sheep SUCCINCT VERSION 2017 status ho decides what breed is rare, by keeping alternative livestock Wand why, varies depending on and poultry genetic resources where you are in the world and how secure; ◆ ensure the availability the people making those evaluations of broad genetic diversity for the interpret their task. The information continued evolution of agricul- here comes from the United States ture; ◆ conserve valuable genetic and the United Kingdom and gives traits such as disease resistance, Karakul (American) Karakul a context and structure for under- survival, self-sufficiency, fertility, standing similar activities elsewhere longevity, foraging ability, maternal factors reflecting the vulnerability of on the globe. Each group that instincts; ◆ preserve our heritage, the overall population. studies livestock breeds and assigns history, and culture; ◆ maintain a conservation category goes by breeds of animals that are well-suit- Between 1900 and 1973, the United fundamental sets of population data ed for sustainable, grass-based and Kingdom lost 26 of its native breeds. and then adjusts for other variables. organic systems; and ◆ give small . Even though many of the UK’s native family farms raising heritage breeds breeds were no longer considered a competitive edge. economically viable for the mass pro- duction of food, their many other im- The Livestock Conservancy, established portant attributes such as adaptation 1977, http://livestockconservancy.org. to the local environment, the genetic Navajo-Churro Known as the American Minor Breeds diversity they represented and their The Livestock Conservancy Conservancy; the American Livestock close links to our livestock history and In North America, the Livestock Breeds Conservancy; now The Livestock cultural heritage were recognised by Conservancy. -

8. Cumbria High Fells Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 8. Cumbria High Fells Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 8. Cumbria High Fells Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future.