CORRECTIONS of the RUDOLPHINE NUMBERS Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistory of Transit Searches Danielle BRIOT1 & Jean

Prehistory of Transit Searches Danielle BRIOT1 & Jean SCHNEIDER2 1) GEPI, UMR 8111, Observatoire de Paris, 61 avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014, Paris, France [email protected] 2) LUTh, UMR 8102, Observatoire de Paris, 5 place Jules Janssen, F-92195 Meudon Cedex, France [email protected] Abstract Nowadays the more powerful method to detect extrasolar planets is the transit method, that is to say observations of the stellar luminosity regularly decreasing when the planet is transiting the star. We review the planet transits which were anticipated, searched, and the first ones which were observed all through history. Indeed transits of planets in front of their star were first investigated and studied in the solar system, concerning the star Sun. The first observations of sunspots were sometimes mistaken for transits of unknown planets. The first scientific observation and study of a transit in the solar system was the observation of Mercury transit by Pierre Gassendi in 1631. Because observations of Venus transits could give a way to determine the distance Sun-Earth, transits of Venus were overwhelmingly observed. Some objects which actually do not exist were searched by their hypothetical transits on the Sun, as some examples a Venus satellite and an infra-mercurial planet. We evoke the possibly first use of the hypothesis of an exoplanet transit to explain some periodic variations of the luminosity of a star, namely the star Algol, during the eighteen century. Then we review the predictions of detection of exoplanets by their transits, those predictions being sometimes ancient, and made by astronomers as well as popular science writers. -

Big Data and Big Questions

Big meta Q:Visualization-based discoveries ?? • When have graphics led to discoveries that might not have been achieved otherwise? . Snow (1854): cholera as a water-borne disease Big Data and Big Questions: . Galton (1883): anti-cyclonic weather patterns Vignettes and lessons from the history of data . E.W. Maunder (1904): 11-year sunspot cycle visualization . Hertzsprung/Russell (1911): spectral classes of stars Galton (1863) Snow (1854) Maunder (1904) H/R (1911) Michael Friendly York University Workshop on Visualization for Big Data Fields Institute, Feb. 2015 2 Big meta Q:Visualization-based discoveries ?? Context: Milestones Project • In the history of graphs, what features and data led to such discoveries? . What visual ideas/representations were available? . What was needed to see/understand something new? • As we go forward, are there any lessons? . What are the Big Questions for today? . How can data visualization help? 3 Web site: http://datavis.ca/milestones 4 Vignettes: 4 heros in the history of data visualization Underlying themes • The 1st statistical graph: M.F. van Langren and the Escaping flatland: 1D → 2D → nD “secret” of longitude • • “Moral statistics”: A.M. Guerry and the rise of modern • The rise of visual thinking and explanation social science • Mapping the invisible • Visual tools for state planning: C.J. Minard and the • Data → Theory → Practice Albums de Statistique Graphique in the “Golden Age” Graphical excellence • Mapping data: Galton’s discoveries & visual insight • • Appreciating the rich history of DataVis in what we do today 5 6 1. Big questions of the 17th century Big data of the 17th century • Geophysical measurement: distance, time and • Astronomical and geodetic tables space . -

Theme 4: from the Greeks to the Renaissance: the Earth in Space

Theme 4: From the Greeks to the Renaissance: the Earth in Space 4.1 Greek Astronomy Unlike the Babylonian astronomers, who developed algorithms to fit the astronomical data they recorded but made no attempt to construct a real model of the solar system, the Greeks were inveterate model builders. Some of their models—for example, the Pythagorean idea that the Earth orbits a celestial fire, which is not, as might be expected, the Sun, but instead is some metaphysical body concealed from us by a dark “counter-Earth” which always lies between us and the fire—were neither clearly motivated nor obviously testable. However, others were more recognisably “scientific” in the modern sense: they were motivated by the desire to describe observed phenomena, and were discarded or modified when they failed to provide good descriptions. In this sense, Greek astronomy marks the birth of astronomy as a true scientific discipline. The challenges to any potential model of the movement of the Sun, Moon and planets are as follows: • Neither the Sun nor the Moon moves across the night sky with uniform angular velocity. The Babylonians recognised this, and allowed for the variation in their mathematical des- criptions of these quantities. The Greeks wanted a physical picture which would account for the variation. • The seasons are not of uniform length. The Greeks defined the seasons in the standard astronomical sense, delimited by equinoxes and solstices, and realised quite early (Euctemon, around 430 BC) that these were not all the same length. This is, of course, related to the non-uniform motion of the Sun mentioned above. -

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

EDUB 1760/PHYS 2700 II. The Scientific Revolution Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) The War on Mars Cameron & Stinner A little background history Where: Holy Roman Empire When: The thirty years war Why: Catholics vs Protestants Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 2 A little background history Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 3 The short biography • Johannes Kepler was born in Weil der Stadt, Germany, in 1571. He was a sickly child and his parents were poor. A scholarship allowed him to enter the University of Tübingen. • There he was introduced to the ideas of Copernicus by Maestlin. He first studied to become a priest in Poland but moved Tübingen Graz to Graz, Austria to teach school in 1596. • As mathematics teacher in Graz, Austria, he wrote the first outspoken defense of the Copernican system, the Mysterium Cosmographicum. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 4 Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) Kepler's Platonic solids model of the Solar system. He sent a copy . to Tycho Brahe who needed a theoretician… Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 5 The short biography Kepler was forced to leave his teaching post at Graz and he moved to Prague to work with the renowned Danish Prague astronomer, Tycho Brahe. Graz He inherited Tycho's post as Imperial Mathematician when Tycho died in 1601. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 6 The short biography Using the precise data (~1’) that Tycho had collected, Kepler discovered that the orbit of Mars was an ellipse. In 1609 he published Astronomia Nova, presenting his discoveries, which are now called Kepler's first two laws of planetary motion. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 7 Tycho Brahe The Aristocrat The Observer Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 8 Tycho Brahe - the Observer The Great Comet of 1577 -from Brahe’s notebooks Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 9 Tycho Brahe’s Cosmology …was a modified heliocentric one Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 10 The short biography • In 1612 Lutherans were forced out of Prague, so Kepler moved on to Linz, Austria. -

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries*

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries* Jean-Pierre Luminet Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM) CNRS-UMR 7326 & Centre de Physique Théorique de Marseille (CPT) CNRS-UMR 7332 & Observatoire de Paris (LUTH) CNRS-UMR 8102 France E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We discuss the reception of Copernican astronomy by the Provençal humanists of the XVIth- XVIIth centuries, beginning with Michel de Montaigne who was the first to recognize the potential scientific and philosophical revolution represented by heliocentrism. Then we describe how, after Kepler’s Astronomia Nova of 1609 and the first telescopic observations by Galileo, it was in the south of France that the New Astronomy found its main promotors with humanists and « amateurs écairés », Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and Pierre Gassendi. The professional astronomer Jean-Dominique Cassini, also from Provence, would later elevate the field to new heights in Paris. Introduction In the first book I set forth the entire distribution of the spheres together with the motions which I attribute to the earth, so that this book contains, as it were, the general structure of the universe. —Nicolaus Copernicus, Preface to Pope Paul III, On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543.1 Written over the course of many years by the Polish Catholic canon Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) and published following his death, De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is regarded by historians as the origin of the modern vision of the universe.2 The radical new ideas presented by Copernicus in De revolutionibus * Extended version of the article "The Provençal Humanists and Copernicus" published in Inference, vol.2 issue 4 (2017), on line at http://inference-review.com/. -

Hipparchus's Table of Chords

ApPENDIX 1 Hipparchus's Table of Chords The construction of this table is based on the facts that the chords of 60° and 90° are known, that starting from chd 8 we can calculate chd(180° - 8) as shown by Figure Al.1, and that from chd S we can calculate chd ~8. The calculation of chd is goes as follows; see Figure Al.2. Let the angle AOB be 8. Place F so that CF = CB, place D so that DOA = i8, and place E so that DE is perpendicular to AC. Then ACD = iAOD = iBOD = DCB making the triangles BCD and DCF congruent. Therefore DF = BD = DA, and so EA = iAF. But CF = CB = chd(180° - 8), so we can calculate CF, which gives us AF and EA. Triangles AED and ADC are similar; therefore ADIAE = ACIDA, which implies that AD2 = AE·AC and enables us to calculate AD. AD is chd i8. We can now find the chords of 30°, 15°, 7~0, 45°, and 22~0. This gives us the chords of 150°, 165°, etc., and eventually we have the chords of all R P chord 8 = PQ, C chord (180 - 8) = QR, QR2 = PR2 _ PQ2. FIGURE A1.l. 235 236 Appendix 1. Hipparchus's Table of Chords Ci"=:...-----""----...........~A FIGURE A1.2. multiples of 71°. The table starts: 2210 10 8 2 30° 45° 522 chd 8 1,341 1,779 2,631 3,041 We find the chords of angles not listed and angles whose chords are not listed by linear interpolation. For example, the angle whose chord is 2,852 is ( 2,852 - 2,631 1)0 . -

Interacting with Data

Interacting with Data L´eonBottou NEC Labs America COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Summary - Three short stories. - Practical information about the course. L´eonBottou 2/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { The orbit of Mars Suppose you are ancient Greeks watching the sky. { Stars move in unison. Like a big sphere. { The Sun and the Moon follow nice trajectories relative to the stars. Like points sitting on interior spheres. { The Planets are bizarre. • Mercury and Venus never go very far from the Sun. • Mars, Jupiter and Saturn follow very strange trajectories. L´eonBottou 3/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { Retrograde Motion Mars makes really strange moves. Jupiter and Saturn do the same, but that takes a lot longer. L´eonBottou 4/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { Cycles and Epicycles Aristotle (384-322BC), Ptolemy (90-168AD) : 53 to 55 spheres. Copernicus : Puts the Sun in the center. Keeps the spheres. Observation tables were not accurate enough to sort them out. L´eonBottou 5/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { The Characters Tycho Brahe Johannes Kepler 1546-1601 1571-1630 L´eonBottou 6/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { Tycho's Observatories First in Uraniborg. Then near Prague, thanks to a \grant" from emperor Rudolf II. There he hires a bright young assistant named Johannes Kepler. Without telescope, but with a modern approach to data collection: { daily observation of 1000 stars and 7 planets, { record positions ±10 arc. L´eonBottou 7/35 COS 424 { 2/2/2010 Story 1 { The Rudolphine Tables The Tabulae Rudolphinae were finally published by Kepler in 1627 under emperor Ferdinand. -

Perkins, "Johannes Kepler

The Objective View June 2008 Newsletter of the Northern Colorado Astronomical Society Nate Perkins, President Chamberlin Observatory Open House, dusk to 10 pm pres@ 970 207 0863 Jun 7, Jul 12, Aug 9, Sep 6 303 871 5172 Greg Halac, Vice President, Web Editor http://www.du.edu/~rstencel/Chamberlin/ vp@ 970 223 7210 Dave Chamness, Secretary and AL Correspondent Longmont Astronomical Society June 19 7 pm sec@ 970 482 1794 Dr. Emily Haynes, Phoenix Mars Lander FRCC, 2121 Miller Rd. See new web page design at: Robert Michael, Treasurer http://www.longmontastro.org/ treas@ 970 482 3615 Dan Laszlo, Newsletter Editor Cheyenne Astronomical Society June 20 9 pm objview@ Office 970 498 9226 Cheyenne Botanic Garden add ncastro.org to complete email address http://home.bresnan.net/~curranm/ Next Meeting: June 5, 7:00 pm May 1 Program Telescope Help Session and Johannes Kepler, His Life and Discoveries Annual NCAS Potluck Picnic by Nate Perkins, Ph.D., Avago Technologies Discovery Science Center Johannes Kepler wrestled tradition and personal tragedies to 703 E Prospect Ave, Fort Collins find truth by the scientific method. His lifetime from 1571 to 1630 was a period for recognition of the power of observation. http://www.ncastro.org/Sites/DiscoveryCtr.htm He was the first to publish natural laws in the scientific sense. His laws of planetary motion are universal, verifiable, and precise. He proposed tides are caused by the Moon, and that Club Brochure: http://www.ncastro.org/Contrib/2008_Brochure.pdf the Sun rotates. He coined the term “satellite.” He made NCAS Programs several novel contributions to optics. -

Lecture 13 – Kepler and Newton's Laws

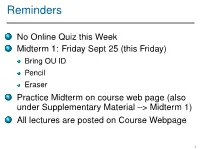

Reminders 1 No Online Quiz this Week 2 Midterm 1: Friday Sept 25 (this Friday) Bring OU ID Pencil Eraser 3 Practice Midterm on course web page (also under Supplementary Material –> Midterm 1) 4 All lectures are posted on Course Webpage 1 Lecture 13 – Kepler and Newton’s Laws 2 Aristotle 3 Aristotle’s Teaching Earth is center of the universe. Gravity is due to the fact that things want to move towards the center of the universe. Heavy things move faster than light things. Earth is corruptible, things change on it. Heavens are perfect and unchanging. Knew Earth was round. 4 End of Classical Greece Ptolemy’s system and textbook Almagest (the greatest, renamed by the Arabs) remained virtually unchanged until the 13th century. With the end of classical Greece, pursuit of knowledge passed to the Arab world. (The Romans did little to further scientific knowledge) Arabs updated the tables several times, remember precession causes them to become out of date. 5 Ptolemy 6 Fly in the ointment: Retrograde Motion of Mars 7 Astronomy in the Dark Ages in 13th Century Arabs were driven out of Spain by Christians, Ptolemy’s book became more widely available in Latin. Last great adjustment of Ptolemy’s system financed by Alfonso X of Castille: Alfonsine Tables The Renaissance was beginning in Europe 8 Critics of Aristotle and Ptolemy Heraclides: A Pythagorean who explained the diurnal motion of the stars by positing an eastward axial rotation of the central earth. Nicole Oresme (14th Century A.D.) member of the Parisian nominalist school. Formulated what we now call Galilean Relativity Critics rejected due to lack of parallax How does this illustrate the workings of the scientific method? 9 Copernicus 1473-1543 Wrote De Revoluionibus Orbium Coelestium (De Reb) around 1530, not published until year of his death. -

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Jean-Pierre Luminet

The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Jean-Pierre Luminet To cite this version: Jean-Pierre Luminet. The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. International Review of Science, 2017. hal-01777594 HAL Id: hal-01777594 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01777594 Submitted on 25 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Reception of the Copernican Revolution Among Provençal Humanists of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries* Jean-Pierre Luminet Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM) CNRS-UMR 7326 & Centre de Physique Théorique de Marseille (CPT) CNRS-UMR 7332 & Observatoire de Paris (LUTH) CNRS-UMR 8102 France E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We discuss the reception of Copernican astronomy by the Provençal humanists of the XVIth- XVIIth centuries, beginning with Michel de Montaigne who was the first to recognize the potential scientific and philosophical revolution represented by heliocentrism. Then we describe how, after Kepler’s Astronomia Nova of 1609 and the first telescopic observations by Galileo, it was in the south of France that the New Astronomy found its main promotors with humanists and « amateurs écairés », Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and Pierre Gassendi. -

2.6 Tycho and Kepler

2.6 Tycho and Kepler PRE-LECTURE READING 2.6 • Astronomy Today, 8th Edition (Chaisson & McMillan) • Astronomy Today, 7th Edition (Chaisson & McMillan) • Astronomy Today, 6th Edition (Chaisson & McMillan) VIDEO LECTURE • Tycho and Kepler1 (21:16) SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) • See Tycho Brahe2. • Geo-heliocentrist (Earth at center, sun orbits Earth, planets orbit sun) • Best pre-telescopic astrometer • Astrometry (not astronomy) is the practice of accurately measuring positions (right ascen- sions and declinations) of astronomical objects in the sky. Tycho could do this to arcminute accuracy. • With accurate astrometry, Tycho: • Found that the supernova of 1572 had no measurable parallax, using a baseline of a fraction of Earth's diameter. (For a mathematical treatment of parallax, see Mea- suring the Astronomical Unit.) This implied that the supernova was significantly farther away than the moon, contradicting the geocentric idea that everything be- yond the moon's sphere is eternal and unchanging. • Similarly found that the comet of 1577 had no measurable parallax, implying that it too was significantly farther away than the moon, again contradicting this geocentric idea. • Compiled the most accurate catalogue of planetary positions to date. Kepler would later use these data to develop and test his own, heliocentric ideas. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) • See Johannes Kepler3. • Heliocentrist 1http://youtu.be/dMnSL4jk5tU 2http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tycho Brahe 3http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes Kepler c 2011-2014 Advanced -

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion: 1609-1666 J. L. Russell the British Journal for the History of Science, Vol

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion: 1609-1666 J. L. Russell The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 2, No. 1. (Jun., 1964), pp. 1-24. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0007-0874%28196406%292%3A1%3C1%3AKLOPM1%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Q The British Journal for the History of Science is currently published by Cambridge University Press and The British Society for the History of Science. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/cup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected].