Mentoring the Future Film Guide for Faith Based Groups & Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

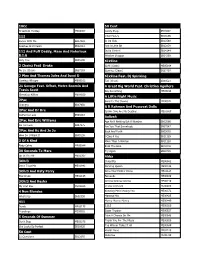

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

Mentoring the Future Parents Guide by M. Dane Zahorsky for Warrior Films

Mentoring the Future Parents Guide by M. Dane Zahorsky for Warrior Films If you RESPECT me, I will hear you. If you LISTEN to me, I will feel understood. If you UNDERSTAND me, I will feel appreciated. If you APPRECIATE me, I will know your support. If you SUPPORT me as I try new things, I will become responsible. When I am RESPONSIBLE, I will grow to be independent. In my INDEPENDENCE, I will respect you and love you all of my life. Thank you! Your teen, -Diana Sterling "Parent as Coach" http://dianasterling.com/ Image Courtesy of: Rite of Passage - Journeys Table of Contents Introduction and Intentions 4 What is Whole Person Development? 5 Rites of Passage 5 Engaged Mentorship 7 What Can I Do? 8 Example Discussion & Action Timeline 11 External Resources / Reading List 15 Supplemental Documents: SEARCH Institute 40 Developmental Assets for Adolescents 18 Supplemental Documents: Core vs. Constructed Identity Mapping 20 Supplemental Documents: Healthy assertion 22 Supplemental Documents: Emotional Literacy 23 Supplemental Documents: Johari Window – Comparing Perception to Reality 25 Supplemental Documents: The Power of Gift in Mentorship 26 Supplemental Documents: SMART Goals, Individualized Milestones and Capstone Projects 27 Supplemental Documents: Culture Mapping 31 Supplemental Documents: The Cycle Of Growth – Roleplaying 32 Supplemental Documents: Sitting In Circle 35 Supplemental Documents: Holding Effective Groups 36 Supplemental Documents: Stephen Foster – Wilderness Rites of Passage for Youth 38 School of Lost Borders Film Study Guide 39 Introduction and Intentions: The intention of this toolkit is to provide you with information, ideas, prompts, and resources drawn from the film Rites of Passage: Mentoring the Future that should reduce stress with your teen(s) and make your overall family life more rewarding and meaningful. -

Excesss 2017-Jan-March by Artist

Excesss 2017-Jan-March by Artist Artist Song Title Artist Song Title Adele Daydreamer Chainsmokers, The Paris Remedy Chainsmokers, The & Daya Don't Let Me Down Water Under The Bridge Chance The Rapper & 2 No Problem Alaina, Lauren Queen Of Hearts Chainz & Lil Wayne Road Less Traveled, The Charli XCX & Lil Yachty After The Afterparty Aldean, Jason Any Ol' Barstool Chesney, Kenny Bar At the End of the Little More Summertime, World A Rich & Miserable Alice in Chains Fear the Voices Childish Gambino Redbone Nutshell Christmas/Terry, Matt When Christmas Comes Amine Caroline Around Aoki, Steve & Louis Just Hold On Church, Eric Kill A Word Tomlinson Clarkson, Kelly It's Quiet Uptown Arthur, James Safe Inside Clean Bandit & Sean Paul Rockabye Say You Won't Let Go & Anne-Marie Say You Wouldn't Let Go Coldplay Everglow Ashanti Helpless Combs, Luke Hurricane B-52's, The Dance This Mess Around Cooper, JP September Song Meet The Flintstones Craig, Adam Just a Phase Badu, Erykah Back in the Day (puff) Cullum, Jamie Old Devil Moon Band Perry, The Stay in the Dark David, Craig Change My Love Beathard, Tucker Rock On Day, Andra Burn Beatles, The I Want You (She's So Rise Up Heavy) Degraw, Gavin She Sets the City On Fire Bellion, Jon All Time Low Depeche Mode Strangelove Big Sean Bounce Back Stripped Bjork Bachelorette Dirty Heads That's All I Need Joga DJ Snake & Justin Bieber Let Me Love You Play Dead Dr Dre Keep Their Heads Ringin' Blunt, James Love Me Better Drake Fake Love Bone Thugs 'n' Harmony Crossroads Dropkick Murphys I'm Shipping Up To Boston -

Tinie Tempah

GIOVEDì 2 FEBBRAIO 2017 Il nuovo singolo "Text From My Ex" di Tinie Tempah con il featuring della star americana dell'R&B Tinashe, ha esordito come più alta nuova entrata nella classifica singoli UK settimana scorsa anticipando il disco di Tinie Tempah: "Text From My Ex" è prossima uscita 'Youth'. il nuovo singolo che anticipa l'album Youth "Text From Your Ex" racchiude tutta la magia e i migliori elementi che hanno da sempre costituito le hit di Tinie: rime vivaci, cariche di personalità accompagnate sempre da ritornelli che ti rimangono ben L'artista sarà in concerto in Italia sabato 1 Aprile piantati nella testa e non ti mollano più. ai Magazzini Generali di Milano 'Text From Your Ex' è stato inoltre prodotto da Jax Jones, noto di recente per il brano 'You Don't Know Me'. CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Tinie spiega riguardo al brano: "Text from your ex, racconta quel momento nella tua giovinezza ('Youth' appunto è poi anche il titolo dell'album) in cui ti senti un tipo figo che ha tante ragazze e la tua donna scopre un messaggio sul tuo telefono e allora te la fai sotto e tutta la tua sicurezza in te stesso si dissolve in un secondo e tu dici 'cavoli è la fine!'. [email protected] E' una storia di vita reale e so che molti ci si possono ritrovare" SPETTACOLINEWS.IT L'album di prossima uscita 'Youth' è stato registrato negli studi di Tinie a Greenwich - un posto a 10 minuti dalla casa dove è cresciuto e non nell'epicentro del music business londinese. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

By Song Title

Solar Entertainments Karaoke Song Listing By Song Title 3 Britney Spears 2000s 17 MK 2010s 22 Lily Allen 2000s 39 Queen 1970s 679 Fetty Wap 2010s 711 Beyonce 2010s 1973 James Blunt 2000s 1999 Prince 1980s 2002 Anne Marie 2010s #ThatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 2010s 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & The Aces 1960s 1 800 273 8255 Logic & Alessia Cara & Khalid 2010s 1 Thing Amerie 2000s 10/10 Paolo Nutini 2010s 10000 Hours Dan & Shay & Justin Bieber 2010s 18 & Life Skid Row 1980s 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 1990s 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2000s 20th Century Boy T Rex 1970s 21 Guns Green Day 2000s 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 2000s 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard 2000s 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 2010s 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2010s 2U David Guetta & Justin Bieber 2010s 3 AM Busted 2000s 3 Nights Dominic Fike 2010s 3 Words Cheryl Cole 2000s 30 Days Saturdays 2010s 34+35 Ariana Grande 2020s 4 44 Jay Z 2010s 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 2000s 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2000s 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 2000s 5,6,7,8 Steps 1990s 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) Proclaimers 1980s 7 Rings Ariana Grande 2010s 7 Things Miley Cyrus 2000s 7 Years Lukas Graham 2010s 74 75 Connells 1990s 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 1980s 90 Days Pink & Wrabel 2010s 99 Red Balloons Nena 1980s A Bad Dream Keane 2000s A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole 1950s A Change Would Do You Good Sheryl Crow 1990s A Cover Is Not The Book Mary Poppins Returns Soundtrack 2010s A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers 1990s A Different Beat Boyzone 1990s A Different Corner George Michael 1980s -

Cdg-Mp3 Karaoke: S – Z - 13.631 Datotek

Cdg-Mp3 karaoke: S – Z - 13.631 datotek S Club - Alive [SF Karaoke] S Club - Love Ain't Gonna Wait For You [SF Karaoke] S Club - Say Goodbye [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Alive [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Best Friend [Homestar Karaoke] S Club 7 - Best Friend [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Bring It All Back [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Bring It All Back [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [AS Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SB Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [Z Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [Homestar Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - I'll Be There [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Love Ain't Gonna Wait For You [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [MM Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had a Dream Come True [NS Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [STW Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [Z Karaoke] S Club 7 - S Club Party [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - S Club Party [SC Karaoke] -

Tinie Tempah

MERCOLEDì 12 APRILE 2017 Esce venerdì 14 aprile 'Youth' il nuovo album di Tinie Tempah, accompagnato dal singolo 'Text from your ex' che ha esordito come più alta nuova entrata nella classifica singoli UK, da 'Mamacita' feat Wizkid, Tinie Tempah: esce venerdì 14 'Girls Like' feat Zara Larsson (Disco D'Oro in Italia) e 'Not Letting Go' feat aprile il suo nuovo album "Youth" Jess Glynne (Disco di Platino in Italia). Il nuovo singolo "Find Me" in radio prossimamente prevede la collaborazione con Jake Bugg. La star planetaria, con all'attivo HIT come 'Written in the stars' e 'Miami 2 CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Ibiza' che vantano oltre 200 milioni di views su Youtube, torna con un album che racchiude tutte le caratteristiche che hanno fatto di lui un artista di fama internazionale tra i più originali e interessanti. In 'Youth' si fondono vari generi, dalla garage, al grime, all'hip-hop e l'R&B, che sono stati dei punti di riferimento per Tinie fin da giovane (da qui il titolo) e che danno vita un album un po' nostalgico con elementi [email protected] del grande suono British in cui emergono i tanti stimoli e le diverse SPETTACOLINEWS.IT culture musicali che si respirano in una città come Londra, città in cui è cresciuto e ha registrato l'album. "Quest'album è anche un incoraggiamento alle nuove generazioni ad uscire fuori dal proprio guscio " spiega Tinie "sono stato anch'io un ragazzino del sud di Londra che amava la musica, che voleva conoscere il mondo e fornire il suo contributo a qualcosa che amava e per cui nutriva una forte passione. -

To Download The

10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10cc Donna Dreadlock Holiday Good Morning Judge I'm Mandy, Fly Me I'm Not In Love Life Is A Minestrone One-Two-Five People In Love Rubber Bullets The Things We Do For Love The Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1975, The Chocolate Love Me Robbers Sex Somebody Else The City The Sound TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME UGH! 2 Chainz ft Wiz Khalifa We Own It 2 Eivissa Oh La La La 2 In A Room Wiggle It 2 Play ft Thomas Jules & Jucxi D Careless Whisper 2 Unlimited No Limit Twilight Zone 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24KGoldn ft Iann Dior Mood 2Pac ft Dr. Dre UPDATED: 28/08/21 Page 1 www.kjkaraoke.co.uk California Love 2Pac ft Elton John Ghetto Gospel 3 Days Grace Just Like You 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Here Without You 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 3 Of Hearts The Christmas Shoes 30 Seconds To Mars Kings & Queens Rescue Me The Kill (Bury Me) 311 First Straw 38 Special Caught Up In You 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 3OH!3 ft Katy Perry Starstrukk 3OH!3 ft Ke$ha My First Kiss 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T ft Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up What's Up (Acoustic) 411, The Dumb UPDATED: 28/08/21 Page 2 www.kjkaraoke.co.uk On My Knees Teardrops 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia Don't Stop Girls Talk Boys Good Girls Jet Black Heart She Looks So Perfect She's Kinda Hot Teeth Youngblood 50 Cent Candy Shop In Da Club Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent ft Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent ft Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 50 Cent ft Nate Dogg 21 Questions 50 Cent ft Ne-Yo Baby By Me 50 Cent ft Snoop Dogg & -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Song Id Song Id 10,000 Maniacs 3T Because The Night 2-64 Anything 634-02 Candy Everybody Wants 985-93 3T & Michael Jackson Like The Weather 27-89 Why 661-01 More Than This 28-45 4 00 Pm 10CC Sukiyaki 16-59 Donna 671-01 4 Non Blondes Dreadlock Holiday 610-01 What's Up 24-54 I'm Mandy 660-01 411 I'm Not In Love 61-01 Dumb 920-05 Rubber Bullets 653-01 On My Knees 797-01 Things We Do For Love, The 889-01 Teardrops 803-01 Wall Street Shuffle 871-01 42nd Street 112 Lullaby Of Broadway 7-31 Peaches & Cream 78-09 Party's Over, The 8-93 17 East 4him Steam 613-01 Basics Of Life 311-19 1910 Fruitgum Co. For Future Generations 304-28 Simon Says 615-01 5 Heartbeats 1975, The Are You Ready For Me 323-14 Chocolate 437-13 5 Seconds Of Summer City, The 452-16 Amnesia 463-12 Love Me 483-13 Don't Stop 461-17 Robbers 462-12 Girls Talk Boys 492-13 Sound, The 486-09 Good Girls 466-07 2 Pac Jet Black 581-01 California Love 634-01 She Looks So Perfect 459-05 2 Unlimited She's Kinda Hot 480-04 No Limits 918-01 Youngblood 516-05 21 Savage & Offset Metro Boomin And Tr 5 Stairsteps Ghostface Killers 508-12 Ooh Child 320-11 21st Century Girls 50 Cent 21st Century Girls 721-01 Candy Shop 169-07 3 Colours Red In Da Club 166-01 Beautiful Day 711-01 50 Cent & Eminem & Adam Levine 3 Doors Down My Life (clean) 435-06 Be Like That 294-23 50 Cent & Justin Timberland & Timbaland Duck And Run 299-11 Ayo Technology 931-08 Here Without You 322-31 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Kryptonite 20-70 21 Questions 789-01 When I'm Gone 310-29 50 Cent & Snoop Dog & Young Jeezy 30