Houston's Flooding Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1030201895310PM.Pdf

Dwight A. Boykins Houston City Council Member, District D October 29, 2018 Beth White President & CEO Houston Parks Board 300 North Post Oak Blvd. Houston, TX 77024 RE: Houston Parks Board / Houston Parks and Recreation Department submissions for H-GAC Call for Projects 2018 Dear Ms. White, I am pleased to send this letter in support of Houston Parks Board’s application for Transportation Improvement Project funding. As a City of Houston Council Member, I support uniting the city by developing a network of off-road shared use paths where residents can walk and bike safely. Expanding our network of greenways that reach jobs, education, and other services makes it easier for residents to rely on biking and walking to go about their daily lives. This reduces stress on people, on our roads, and on household budgets. The Beyond the Bayous Regional Connector Network of Greenways offers a vision to broaden the reach of Bayou Greenways 2020. Its inclusion in the 2045 Regional Transportation Plan will provide a roadmap for a comprehensive network of connected greenway trails throughout Harris County. The Port Connector Greenway project links the Port of Houston Turning Basin to Buffalo, Brays and Sims Bayou Greenways, and ultimately to Hobby Airport. It also creates a link to the west along Navigation, connecting to the trails at Buffalo Bayou Park East leading to downtown. These projects create neighborhood connections to existing parks, METRO lines, employment centers and residential areas in District D, and both are deserving. If you have any questions or concerns, please feel free to contact me directly. -

Ebb and Flow: a Geographic Look at Houston's Stormy History

Ebb and Flow A Geographic Look at Houston's Stormy History Joshua G. Roberson Publication 2196 March 6, 2018 eographically, the Houston-The Woodlands- Sugar Land Metropolitan Statistical Area is one The Takeaway Gof the largest metropolitan areas in the nation. While it’s still too early to determine Hurricane Despite fluctuations in the oil market, it is also one of Harvey’s long-term impact on Houston’s hous- the most densely populated metros with steady house- ing market, the city’s history of flooding provides hold growth. When Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas Gulf clues on what to expect. Neighborhoods near bay- Coast in late August and unleashed unprecedented levels ous and waterways suffered severe flood damage, of rain in a short time, Houston received the bulk of but, overall, the housing market emerged from the property damage due to its size. Total damage estimates storm in relatively good shape. are anticipated to rival other catastrophic hurricanes such as Sandy and Katrina. Short- and long-term economic losses could be severe. and one particular area that has been hit hard numerous How will this storm and its torrential flooding affect times by recent floods. The goal was to help model pos- area home sales? While it is still too early to judge the sible outcomes for similar markets impacted by Harvey. storm’s total long-term impact, Houston has a long his- The Houston metro comprises Austin, Brazoria, Cham- tory of storms and floods to guide expectations. bers, Fort Bend, Galveston, Harris, Liberty, Montgom- ery, and Waller Counties. -

Buffalo and Whiteoak Bayou Tmdl

Total Maximum Daily Loads for Fecal Pathogens in Buffalo Bayou and Whiteoak Bayou Contract No. 582-6-70860 Work Order No. 582-6-70860-21 TECHNICAL SUPPORT DOCUMENT FOR BUFFALO AND WHITEOAK BAYOU TMDL Prepared by University of Houston CDM Principal Investigator Hanadi Rifai Prepared for Total Maximum Daily Load Program Texas Commission on Environmental Quality P.O. Box 13087, MC - 150 Austin, Texas 78711-3087 TCEQ Contact: Ronald Stein TMDL Team (MC-203) P.O. Box 13087, MC - 203 Austin, Texas 78711-3087 [email protected] MAY 2008 Contract #- -582-6-70860/ Work Order # 582-6-70860-21 –Technical Support Document TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………..……………..….vi LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………..……… ... ….ix CHAPTER 1 : PROBLEM DEFINITION...................................................................................... 1 1.1 WATERSHED DESCRIPTION................................................................................. 1 1.2 ENDPOINT DESIGNATION.................................................................................... 5 1.3 CRITICAL CONDITION........................................................................................... 8 1.4 MARGIN OF SAFETY.............................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER 2 : SUMMARY OF EXISTING DATA...................................................................... 9 2.1 WATERSHED CHARACTERISTICS...................................................................... 9 2.1.1 LAND USE........................................................................................................ -

Karen Stokes Dance Presents "Sunset at White Oak Bayou"

Contact: Karen Stokes FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: 832-794-5825 April 15, 2015 Karen Stokes Dance presents "Sunset at White Oak Bayou" Houston, TX. – Karen Stokes loves Houston history – especially the kind of tidbits largely unknown to the public. For instance, Houston was founded on the creation of a myth. The original founders of Houston, the Allen Brothers, marketed the Buffalo Bayou as "having an abundance of excellent spring water and enjoying the sea breeze in all its freshness. ... It is handsome and beautifully elevated, salubrious and well-watered." This entrepreneurial exaggeration, along with the statement that the newly founded Houston was a thriving port rather than a few muddy streets riddled with mosquitoes, brought settlers to Texas. Thus began the settlement of the fourth largest city in America. For Stokes, this is fertile ground for dance-making. Karen Stokes Dance presents "Sunset at White Oak Bayou" a site specific work at White Oak Bayou on October 18, 2015. With original music by Brad Sayles, played live by Heights 5 Brass, Karen Stokes Dance brings to life Houston’s origins in its original setting. Stokes is making it her mission to bring Houston history alive in the very spot the Allen’s Brothers stepped ashore, on the banks of White Oak Bayou as it merges with Buffalo Bayou. This site, the original Port of Houston, (now renamed Allen’s Landing after its founders) has been a central focus of Stokes’ work for two years. “Sunset at White Oak Bayou” is the third installment in her series of Houston historical sites. -

White Oak Bayou Partnership – CDBG‐MIT Grant

General Acknowledging that mitigation needs may span a variety of services and facilities, for purposes of Mitigation funding only, the definition of project is expanded to include a discrete and well-defined beneficiary population and subsequent geographic location consisting of a ll eligible a ctivities required to complete and provide specific successful mitigation benefit to the identified population. For purposes of Mitigation a pplication a nd implementation, the Project provided represents the overall Mitiga tion need being met. There may be more than one Activity included in a Project. For instance, a successful Mitigation Project may require a drainage fa cilities a ctivity, a street improvements a ctivity, a nd a wa ter facilities a ctivity. Program Hurricane Harvey State Mitigation Competition – HUD MID Subrecipient Application/Contract White Oak Bayou Partnership Application Project Title White Oak Bayou Partnership Drainage Improvements Project Summary The White Oak Bayou Watershed has experienced multiple major flooding events in recent years including the Memorial Day Flood (2015), the Tax Day Flood (2016) and Hurricane Harvey (2017). These events have amounted to 84 deaths and over $125.5 billion in damages. Because of the devastation and the need to identify measures to mitigation the impacts of major storm events, Harris County studied nearly 100 previously flooded subdivisions and Harris County Flood Control District identified regional solutions, finding drainage alternatives to mitigate risk to life and safety during future storm events. This Flood and Drainage Activity improves drainage at a regional and neighborhood level by making improvements to flood control facilities and six subdivisions within the White Oak Bayou Watershed. -

1 3 4 2 Regional Bikeway Spines Conceptual Plan

- 9.2 Miles 3.3 Miles 3.4 Miles 5.2 Miles NORTHEAST Hardy - Elysian - Kelley CENTRAL Austin Corridor EAST Polk - Cullen 1 SOUTHEAST Calhoun - Griggs - MLK Extents: Buffalo Bayou to LBJ Hospital Neighborhoods: Near Northside; Kashmere Gardens; Fifth Ward 2 Destinations: LBJ Hospital; Kashmere Transit Center; 4 HISD schools; Buffalo Bayou Future Connections/Improvements Buffalo Bayou (BG2020); Downtown (Austin Street); Hunting Bayou (BG2020); Fifth Ward (Lyons) Extents: Buffalo Bayou to Hermann Park (Brays Bayou) Neighborhoods: 3 Downtown; Midtown; Museum Park Destinations: Buffalo Bayou; Downtown/Midtown jobs and at tractions; Museum District; Hermann Park Future Connections/Improvements Hermann Park Trails (Master Plan); Buffalo Bayou trail (BG2020) Extents: Lamar Cycle Track to Brays Bayou Neighborhoods: Downtown; East Downtown; Eastwood; Third Ward; MacGregor Destinations: Downtown/GRB; Bastrop Promenade; Columbia 4 Tap; UniversityTap; of Houston; TSU; Brays Bayou Future Connections/Improvements Includes HC Pct. 1 Cullen reconstruction project from IH 45 to Brays Bayou Extents: Brays Bayou to Sims Bayou OATES Neighborhoods: MacGregor; OST/South Union; South Acres; Sunnyside Destinations: UH; Brays Bayou; MacGregor Park; Palm Center; Sims Bayou Future Connections/Improvements Park system along Sims Bayou (BG2020) E MERCURY L A D D T N O ALLEN GENOA O O W R A N N E L E OATES C L L COLLEGE A M U A E B 45 W FIDELITY D R A ALMEDA GENOA ALMEDA MESA GELLHORN W O H MESA CENTRAL STON WINKLER LVE A R G E T S 610 MONROE HOUSTON [ E H C N A A O -

Harris County, Texas and Incorporated Areas VOLUME 1 of 12

Harris County, Texas and Incorporated Areas VOLUME 1 of 12 COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NO. COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NO. Baytown, City of 485456 Nassau Bay, City of 485491 Bellaire, City of 480289 Pasadena, City of 480307 Bunker Hill Village, City of 1 480290 Pearland, City of 480077 Deer Park, City of 480291 Piney Point Village, City of 480308 El Lago, City of 485466 Seabrook, City of 485507 Galena Park, City of 480293 Shoreacres, City of 485510 Hedwig Village, City of1 480294 South Houston, City of 480311 Hilshire Village, City of 480295 Southside Place, City of 480312 Houston, City of 480296 Spring Valley Village, City of 480313 Humble, City of 480297 Stafford, City of 480233 Hunter’s Creek Village, City of 480298 Taylor Lake Village, City of 485513 Jacinto City, City of 480299 Tomball, City of 480315 Jersey Village, City of 480300 Webster, City of 485516 La Porte, City of 485487 West University Place, City of 480318 Missouri City, City of 480304 Harris County Unincorporated Areas 480287 Morgans Point, City of 480305 1 No Special Flood Hazard Areas identified REVISED: November 15, 2019 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 48201CV001G NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the Flood Insurance Study. -

Buffalo Bayou East Master Plan Brings the Community’S Vision for Its Waterfront to Life

Authentic Connected Inclusive Resilient A VISION FOR BUFFALO BAYOU EAST BUFFALO BAYOU PARTNERSHIP MICHAEL VAN VALKENBURGH ASSOCIATES Landscape Architecture HR&A ADVISORS Economic Development HUITT-ZOLLARS Engineering and Transportation LIMNOTECH Hydrology UTILE Urban Design and Architecture The Buffalo Bayou East Master Plan brings the community’s vision for its waterfront to life. Like other cities such as New York, Boston and St. Louis While most of Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s green space where Frederick Law Olmstead designed park systems, development has occurred west of Downtown, for more Houston hired Cambridge, Massachusetts landscape than a decade the organization has been acquiring architect Arthur Coleman Comey in 1912 to provide property and building a nascent trail system along the a plan that would guide the city’s growth. In his plan, waterway’s East Sector. The Buffalo Bayou East Master Houston: Tentative Plans for Its Development, Comey Plan brings the community’s vision for its waterfront asserted: “The backbone of a park system for Houston to life. Informed by significant outreach and engagement, will naturally be its creek valleys, which readily lend the plan envisions integrating new parks and trails, themselves to ‘parking’ … All the bayous should dynamic recreational and cultural destinations, and be ‘parked’ except where utilized for commerce.” connections to surrounding neighborhoods. Building upon Comey’s vision, Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s This plan is an important step forward for the future of (BBP) 2002 Buffalo Bayou and Beyond Master Plan Houston’s historic bayou—a project that will take decades and envisioned a network of green spaces along the Bayou require creative partnerships to unfold. -

I-1 2015 MEMORIAL DAY FLOOD in HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS Michael D. Talbott, P.E. Abstract After Weeks of Intermittent Rainfall Acros

Proceedings THC-IT-2015 Conference & Exhibition 2015 MEMORIAL DAY FLOOD IN HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS Michael D. Talbott, P.E. Executive Director Harris County Flood Control District 9900 Northwest Freeway Houston, Texas 77092 Email: [email protected] , web: www.hcfcd.org Abstract After weeks of intermittent rainfall across Harris County, a slow moving line of thunderstorms moved into Harris County from central Texas during the evening hours of May 25, 2015. Very heavy rainfall began around 8:30 p.m. across the northern portions of Harris County, while additional thunderstorms developed over central Fort Bend County and moved into Harris County from the southwest. A period of thunderstorm cell training occurred from 10:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. from Fort Bend County into north- central Harris County where the cells merged with the line of storms moving southward from northern Harris County. Thunderstorm cell mergers continued over central and southwest Harris County for several hours resulting in widespread significant flooding. A “Flash Flood Emergency” was issued by the National Weather Service for Harris County at 10:52 p.m. on the 25th for the first time ever (although this is a relatively new terminology). The worst rainfall was focused across the western portion of Harris County from the northwest side of the City of Houston to Addicks, Sharpstown, and Richmond in central Fort Bend County. Hundreds of water rescues were performed by various agencies during the height of the rainfall on the 25th and 26th. Rescues were mainly motorists stranded on area freeways and roadways, and after daylight on the 26th, the Houston Fire Department responded to many requests for assistance from residents in flooded homes. -

Flood Reduction Lessons Learned After Major Disasters

Flood Reduction Lessons Learned after Major Disasters: Mitigation Project Performance Post-Harvey and Irma Karen Helbrecht, FEMA Headquarters Lawrence Frank, Atkins North America June 20, 2018 What a year! 2018 ASFPM Conference 2 Mitigation Saves 2.0 • The Institute’s MMC updated and expand upon the 2005 Mitigation Saves study on the value of mitigation • Federal grants: Reviewed 23 years of federal mitigation grants provided by FEMA, the Economic Development Administration (EDA), and HUD National benefit of $6 for every $1 invested • Beyond code requirements: Cost/benefits of designing new construction to exceed select provisions in the 2015 IBC, the 2015 IRC, and implementation of the 2015 International Wildland-Urban Interface Code National benefit of $4 for every $1 invested 2018 ASFPM Conference 3 Mitigation Saves 2.0 FLOOD MITIGATION GRANTS 2018 ASFPM Conference 4 Texas High Water Mark Comparison Between Tropical Storm Allison (6/9/01) and Hurricane Harvey (8/27/17) - estimated HWMs Location Allison Harvey HWM HWM Interstate 45 / Clear Creek 10.7 16.6 Interstate 45 / Sims Bayou 20.5 22.1 Rice Boulevard / Bray’s Bayou 50.4 54.1 N. Shepherd / White Oak Bayou 49.0 51.3 NASA Road #1 / Armand Bayou 4.7 8.3 Bay Area Boulevard / Horsepen Bayou 14.6 15.7 Spencer Highway / Big Island Slough 18.5 17.3 Astoria / Turkey Creek 29.0 32.2 Source: Harris County Flood Control District website; above 1988 NAVD; 2001 ADJ 2018 ASFPM Conference 5 Texas • Harris County Flood Control District (from website) • Sims Bayou Federal Project with Local Stormwater Detention –70 properties sustained damage during Harvey as opposed to more than 6,570 being damaged • Brays Bayou Project Bray Channel improvements and stormwater detention basins – 10,000 properties not damaged • White Oak Bayou Flood Mitigation projects – reduced damages to an estimated 5,500 structures. -

Bicycle Advisory Committee

Bicycle Advisory Committee BAC Mission To advise and make recommendations to the commission and the director on issues related to bicycling in the city including, but not limited to, amendments to the Bike Plan, bicycle safety and education, implementation of the Bike Plan, development of strategies for funding projects related to bicycling, and promoting public participation in bicycling. BAC Vision By 2027, the City of Houston will be a Safer, More Accessible, Gold Level Bike-Friendly City March 10, 2021 3:30-5:30pm Microsoft Teams Link Committee Member Attendance Tom Compson, Chair Nick Hellyer Alejandro Perez, Vice Chair Judith Villarreal Toloria Allen Amar Mohite Zion Escobar Mike van Dusen Adam J. Williams Ana Ramirez Huerta Sandra Rodriguez Robin Holzer Com. Kristine Anthony-Miller Veon McReynolds Beth Martin Lisa Graiff David Fields Jessica Wiggins Ian Hlavacek Yuhayna Mahmud Juvenal Robles 2 Microsoft Teams Meeting Instructions Agenda & Slides: https://houstonbikeplan.org/bac/ Join by Phone: 936-755-1521 ID: 242 098 915# 3 Microsoft Teams Instructions 4 Agenda 1. Chair’s Report 2. Public Comment 3. Presentation by Bryan Dotson and Gregg Nady Regarding Potential On-Street Connection Between Spring Branch Trail and White Oak Bayou 4. Presentation by Bryan Dotson Regarding Federal Lands Access Program Funding Opportunity for Addicks Reservoir Trails 5. Bikeway Project Updates 6. Implementation of Road Safety Audit Recommendations 7. Maintenance Report Presentation 8. Discussion: Bus Stops along protected bike lanes 9. Announcements The public is invited to speak for up to two (2) minutes each either at the beginning of the meeting or at the end. -

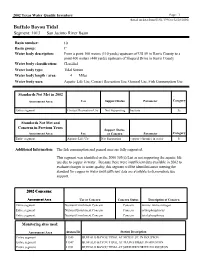

Buffalo Bayou Tidal Segment: 1013 San Jacinto River Basin

2002 Texas Water Quality Inventory Page : 1 (based on data from 03/01/1996 to 02/28/2001) Buffalo Bayou Tidal Segment: 1013 San Jacinto River Basin Basin number: 10 Basin group: C Water body description: From a point 100 meters (110 yards) upstream of US 59 in Harris County to a point 400 meters (440 yards) upstream of Shepard Drive in Harris County Water body classification: Classified Water body type: Tidal Stream Water body length / area: 4 Miles Water body uses: Aquatic Life Use, Contact Recreation Use, General Use, Fish Consumption Use Standards Not Met in 2002 Assessment Area Use Support Status Parameter Category Entire segment Contact Recreation Use Not Supporting bacteria 5a Standards Not Met and Concerns in Previous Years Support Status Assessment Area Use or Concern Parameter Category Entire segment Aquatic Life Use Not Supporting copper (chronic) in water 5c Additional Information: The fish consumption and general uses are fully supported. This segment was identified on the 2000 303(d) List as not supporting the aquatic life use due to copper in water. Because there were insufficient data available in 2002 to evaluate changes in water quality, this segment will be identified asnot meeting the standard for copper in water until sufficient data are available to demonstrate use support. 2002 Concerns: Assessment Area Use or Concern Concern Status Description of Concern Entire segment Nutrient Enrichment Concern Concern nitrate+nitrite nitrogen Entire segment Nutrient Enrichment Concern Concern orthophosphorus Entire segment Nutrient Enrichment Concern Concern total phosphorus Monitoring sites used: Assessment Area Station ID Station Description Entire segment 11345 BUFFALO BAYOU TIDAL AT MCKEE ST.