Module 6 Experimental Tools & Techniques II Lecture 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10-1 CHAPTER 10 DEFORMATION 10.1 Stress-Strain Diagrams And

EN380 Naval Materials Science and Engineering Course Notes, U.S. Naval Academy CHAPTER 10 DEFORMATION 10.1 Stress-Strain Diagrams and Material Behavior 10.2 Material Characteristics 10.3 Elastic-Plastic Response of Metals 10.4 True stress and strain measures 10.5 Yielding of a Ductile Metal under a General Stress State - Mises Yield Condition. 10.6 Maximum shear stress condition 10.7 Creep Consider the bar in figure 1 subjected to a simple tension loading F. Figure 1: Bar in Tension Engineering Stress () is the quotient of load (F) and area (A). The units of stress are normally pounds per square inch (psi). = F A where: is the stress (psi) F is the force that is loading the object (lb) A is the cross sectional area of the object (in2) When stress is applied to a material, the material will deform. Elongation is defined as the difference between loaded and unloaded length ∆푙 = L - Lo where: ∆푙 is the elongation (ft) L is the loaded length of the cable (ft) Lo is the unloaded (original) length of the cable (ft) 10-1 EN380 Naval Materials Science and Engineering Course Notes, U.S. Naval Academy Strain is the concept used to compare the elongation of a material to its original, undeformed length. Strain () is the quotient of elongation (e) and original length (L0). Engineering Strain has no units but is often given the units of in/in or ft/ft. ∆푙 휀 = 퐿 where: is the strain in the cable (ft/ft) ∆푙 is the elongation (ft) Lo is the unloaded (original) length of the cable (ft) Example Find the strain in a 75 foot cable experiencing an elongation of one inch. -

Mechanics of Materials Plasticity

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This article was originally published in the Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Lubarda V.A., Mechanics of Materials: Plasticity. In: Saleem Hashmi (editor-in-chief), Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering. Oxford: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 1-24. ISBN: 978-0-12-803581-8 Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Inc. unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved. Author's personal copy Mechanics of Materials: Plasticity$ VA Lubarda, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA r 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Yield Surface 1 1.1 Yield Surface in Strain Space 2 1.2 Yield Surface in Stress Space 2 2 Plasticity Postulates, Normality and Convexity -

Necking True Stress – Strain Data Using Instrumented Nanoindentation

CORRECTION OF THE POST – NECKING TRUE STRESS – STRAIN DATA USING INSTRUMENTED NANOINDENTATION by Iván Darío Romero Fonseca A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mechanical Engineering Charlotte 2014 Approved by: Dr. Qiuming Wei Dr. Harish Cherukuri Dr. Alireza Tabarraei Dr. Carlos Orozco Dr. Jing Zhou ii ©2014 Iván Darío Romero Fonseca ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT IVÁN DARÍO ROMERO FONSECA. Correction of the post-necking True Stress-Strain data using instrumented nanoindentation. (Under the direction of DR. QIUMING WEI) The study of large plastic deformations has been the focus of numerous studies particularly in the metal forming processes and fracture mechanics fields. A good understanding of the plastic flow properties of metallic alloys and the true stresses and true strains induced during plastic deformation is crucial to optimize the aforementioned processes, and to predict ductile failure in fracture mechanics analyzes. Knowledge of stresses and strains is extracted from the true stress-strain curve of the material from the uniaxial tensile test. In addition, stress triaxiality is manifested by the neck developed during the last stage of a tensile test performed on a ductile material. This necking phenomenon is the factor responsible for deviating from uniaxial state into a triaxial one, then, providing an inaccurate description of the material’s behavior after the onset of necking The research of this dissertation is aimed at the development of a correction method for the nonuniform plastic deformation (post-necking) portion of the true stress- strain curve. -

Dynamics of Large-Scale Plastic Deformation and the Necking Instability in Amorphous Solids

PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS week ending VOLUME 90, NUMBER 4 31 JANUARY 2003 Dynamics of Large-Scale Plastic Deformation and the Necking Instability in Amorphous Solids L. O. Eastgate Laboratory of Atomic and Solid State Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 J. S. Langer and L. Pechenik Department of Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106 (Received 19 June 2002; published 31 January 2003) We use the shear transformation zone (STZ) theory of dynamic plasticity to study the necking instability in a two-dimensional strip of amorphous solid. Our Eulerian description of large-scale deformation allows us to follow the instability far into the nonlinear regime. We find a strong rate dependence; the higher the applied strain rate, the further the strip extends before the onset of instability. The material hardens outside the necking region, but the description of plastic flow within the neck is distinctly different from that of conventional time-independent theories of plasticity. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.045506 PACS numbers: 62.20.Fe, 46.05.+b, 46.35.+z, 83.60.Df Conventional descriptions of plastic deformation in when the strip is loaded slowly. One especially important solids consist of phenomenological rules of behavior, element of our analysis is our ability to interpret flow and with qualitative distinctions between time-independent hardening in terms of the internal STZ variables. and time-dependent properties, and sharply defined yield To make this problem as simple as possible, we consi- criteria. Plasticity, however, is an intrinsically dynamic der here only strictly two-dimensional, amorphous mate- phenomenon. Practical theories of plasticity should con- rials. -

Analysis of Post-Necking Behavior in Structural Steels Using a One-Dimensional Nonlocal Model

Engineering Structures 180 (2019) 321–331 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Engineering Structures journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/engstruct Analysis of post-necking behavior in structural steels using a one- dimensional nonlocal model T ⁎ Yazhi Zhua, Amit Kanvindeb, , Zuanfeng Pana a Department of Structural Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China b Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In modeling necking in steel bars subjected to uniaxial tension using a classical one-dimensional elastoplastic Diffuse necking continuum, numerical results exhibit strong mesh dependency without convergence upon mesh refinement. The Strain localization strain localization and softening with respect to necking in structural steels is induced by hybrid material and Mesh sensitivity geometric nonlinearities rather than material damage. A one-dimensional nonlocal model is proposed to address Nonlocal formulations these numerical difficulties and to provide an enhanced numerical representation of necking-induced localiza- Characteristic length tion in structural steels for the potential implementation in fiber-based formulations. By introducing a char- Structural steels acteristic length and a nonlocal parameter to the standard constitutive model, the enhanced nonlocal continuum provides a well-posed governing equation for the necking problem. The finite element calculations based on this one-dimensional nonlocal model give rise to objective solutions, i.e., numerical results converge under mesh refinement. In addition, the size of the necking region also exhibits mesh-independence. The characteristic length and nonlocal parameter significantly influence the post-necking response and the dimension of the necked region. Comparison of the local and global response of necking between one-dimensional analysis and 3D si- mulations demonstrates that the proposed model is capable of accurately characterizing the post-necking be- havior. -

Measuring the Ductility of Metals

Measuring the Ductility of Metals By Richard Gedney ADMET, Inc. Ductility is defined as the ability of a material to deform plastically before fracturing. Its measurement is of interest to those conducting metal forming processes; to designers of machines and structures; and to those responsible for assessing the quality of a material that it is being produced. Measures of Ductility Two measures of ductility are Elongation and Reduction of Area. The conventional means by which we obtain these measures is by pulling a specimen in tension until fracture. ASTM E8 Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials governs the determination of Elongation and Reduction of Area for metals. Elongation is defined as the increase in the gage length of a test piece subjected to tensile forces divided by the original gage length. Elongation is expressed as a percentage of the original gage length and is given by: ∆푳 푷풆풓풄풆풏풕 푬풍풐풏품풂풕풊풐풏 = × ퟏퟎퟎ Eq. 1 푳ퟎ Where: 푳ퟎ is the original gage length. ∆푳 is the change in length of the original gage length. Measured after the specimen fractures and the specimen is fitted together (see Figure 2). The original gage length, 퐿0, as specified in ASTM E8 is usually 1.0 in, 2.0 in, 4.0 in or 8.0 inches and is dependent on the size of the specimen. A punch is often used to apply the gage marks to each specimen (see Figure 1). The change in gage length, L, is determined by carefully fitting the ends of the fractured specimen together and measuring the distance between the gage marks (see Figure 2). -

ME 4733: Deformation and Fracture of Engineering Materials Problem Set 1

ME 4733: Deformation and Fracture of Engineering Materials Spring 2002 Problem Set 1 1) Hertzberg, 1.3 A 200-mm-long rod with a diameter of 2.5mm is loaded with a 2000-N weight. If the diameter decreases to 2.2 mm, compute the following: (a) The final length of the rod. (b) The true stress and true strain at this load. (c) The engineering stress and strain at this load. Solution: = = (a) Initial state: diameter do 25.mm, l0 200mm = Final state: diameter d f 22.mm, lf Assume this is a constant-volume process d 2 d 2 ππ0 ⋅=l f ⋅l 440 f 2 2 d 25. ⇒ The final length of the rod is l = 0 ⋅=l ⋅=200mm 258. 26 mm f 0 d f 22. P 2000N (b) The true stress is σ = = = 526. 4MPa; true d 22(.22mm ) π ⋅ f 314. ⋅ 4 4 l ε ==f 258. 26 = The true strain is true ln ln 0. 2556. l0 200 P 2000N (c) The engineering stress is σ = = = 407. 4MPa; true d 22(.25mm ) π ⋅ 0 314. ⋅ 4 4 ll− − ε = f 0 = 258. 26 200 = The engineering strain is true 0. 2913. l0 200 Note: (1) In tensile test, the true stress is always higher than engineering stress. How about in compressive state? (2) In tensile test, the true strain is always lower than engineering strain. 2) Hertzberg, 1.8 A 5-cm-long circular rod of 1080 as-rolled steel (diameter=1.28cm) is loaded to failure in tension. What was the load necessary to break the sample? If 80% of the total elongation was uniform in character prior to the onset of localized deformation, computer the true stress at the point of incipient necking. -

Effect of the Specimen Size on Necking Development in Metals and Alloys During Superplastic Deformation A.G

Materials Physics and Mechanics 46 (2020) 1-6 Received: October 27, 2020 EFFECT OF THE SPECIMEN SIZE ON NECKING DEVELOPMENT IN METALS AND ALLOYS DURING SUPERPLASTIC DEFORMATION A.G. Sheinerman* Institute for Problems in Mechanical Engineering, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 199178, Russia Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, St. Petersburg 195251, Russia Saint Petersburg State University, 7/9 Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg 199034, Russia *e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. A model is proposed that describes the development of individual and multiple necks in superplastically deformed materials. Within the model, the examined samples have the form of round bars and are subjected to tensile superplastic deformation without strain hardening. It is demonstrated that neck development and necking-induced failure occur faster with a decrease in strain rate sensitivity and/or an increase in the fraction of the sample length occupied by necks. This means that high values of strain to failure observed in small specimens of superplastically deformed ultrafine-grained metals and alloys, where diffuse necking happens in the whole specimen, can be significantly reduced in larger specimens where the necking regions occupy only a small part of the sample. Keywords: superplastic deformation, necking, ductility, failure, ultrafine-grained materials 1. Introduction It is known that the ductility of metals and alloys under superplastic deformation is often limited by cavitation or diffuse necking (e.g., [1]). In particular, diffuse necking is often observed in ultrafine-grained (ufg) alloys demonstrating superplastic deformation or superplastic behavior (e.g., [2,3]). Due to the difficulty in making nanostructured materials large enough for standard mechanical testing, to measure the mechanical properties of such materials, many researchers have been using small samples [4]. -

Study on True Stress Correction from Tensile Tests Choung, J

Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 22 (2008) 1039~1051 www.springerlink.com/content/1738-494x Study on true stress correction from tensile tests Choung, J. M.1,* and Cho, S. R.2 1Hyundai Heavy Industries Co., LTD, Korea 2School of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering, University of Ulsan, Korea (Manuscript Received June 5, 2007; Revised March 3, 2008; Accepted March 6, 2008) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract Average true flow stress-logarithmic true strain curves can be usually obtained from a tensile test. After the onset of necking, the average true flow stress-logarithmic true strain data from a tensile specimen with round cross section should be modified by using the correction formula proposed by Bridgman. But there have been no firmly established correction formulae applicable to a specimen with rectangular cross section. In this paper, a new easy-to-use formula is presented based on parametric finite element simulations. The new formula requires only incremental plastic strain and hardening exponents of the material, which are simply presented from a tensile test. The newly proposed formula is verified with experimental data for high strength steel DH32 used in the shipbuilding and offshore industry and is proved to be effective during the diffuse necking -

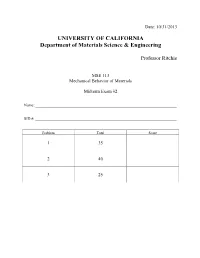

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Department of Materials Science & Engineering

Date: 10/31/2013 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Department of Materials Science & Engineering Professor Ritchie MSE 113 Mechanical Behavior of Materials Midterm Exam #2 Name: ________________________________________________________________________ SID #: ________________________________________________________________________ Problem Total Score 1 35 2 40 3 25 1) Deformation (35 points) You are given a uniaxial tensile specimen, with in a uniform cross-sectional area, of a ductile polycrystalline material that behaves according to the following constitutive law: where and are, respectively, the normal true stress and strain, n is the strain hardening coefficient and k is a scaling constant. a) On the uniaxial tensile stress-strain diagram below, draw and label the following: i. engineering stress vs. engineering strain ii. true stress vs. true strain iii. where necking occurs iv. the ultimate tensile strength, Su b) Briefly explain (3 sentences or less) the difference between true stress-strain and engineering stress-strain diagrams. c) Briefly describe (3 sentences or less) what occurs at the microscopic and macroscopic scales at the onset of: i. plastic deformation ii. necking d) Derive i. an expression relating true stress to engineering stress and engineering strain only ii. an expression relating true strain to engineering strain only iii. expressions for the true and engineering strains at necking Clearly state the assumptions that you make in the derivations Solution 1a) σ ε 1b) True stress-strain compensates for changing cross sectional area, while engineering stress-strain uses the original area. 1c) i. Microscopically, plastic deformation results from dislocation motion and bond breaking. On a macroscopic scale, this results in permanent deformation when the load is removed. -

Stress-Strain Concepts Revisited-Part 2-Issue 46-October 2012

Issue No. 46 – October 2012 Updated from Original May 2004 Publication Stress-Strain Concepts Revisited – Part 2 More stress in your life! – A continued discussion Last month’s edition of Technical Tidbits started to explore the concepts of properties that can that goes back to the be obtained from a material’s stress-strain curve. This is a continuation of that discussion. basics with an in-depth discussion of stress and After the yield strength is exceeded, the stress-strain curve continues to rise to a maximum point strain concepts. known as the tensile strength or the ultimate tensile strength. The strain up to this point is referred to as uniform strain, since the deformation in the specimen is uniform. However, once the tensile strength is exceeded, the test specimen begins to thin down, or neck, at some location along the length. All of the rest of the deformation to failure occurs at this point as the stress is . Tensile concentrated in this area of reduced cross section. Since the engineering stress is determined by Strength dividing the force load by the original cross sectional area, the engineering stress-strain curve begins to slope downward at this point, despite the fact that the actual stress in the specimen . Necking continues to increase. The curve continues until the specimen breaks when the fracture stress is . reached. True Stress & Strain True stress is determined by dividing the load by the smallest actual minimum cross sectional area of the specimen at any given time. The corresponding true strain at each point of the . -

A Theory of Necking in Semi-Crystalline Polymers

A theory of necking in semi-crystalline polymers A. I. Leonov Department of Polymer Engineering, The University of Akron, Akron, Ohio 44325-0301, USA. Abstract Necking or cold drawing is a smoothed jump in cross-sectional area of long and thin bars (filaments or films) propagating with a constant speed. The necks in polymers, first observed about seventy years ago, are now commonly used in modern processing of polymer films and fibers. Yet till recently there was a lack in fundamental understanding of necking mechanism(s). For semi-crystalline polymers with co-existing amorphous and crystalline phases, recent experiments revealed that such a mechanism is related to unfolding crystalline blocks. Using this idea, this paper develops a theoretical model and includes it in a general continuum framework. Additionally, the paper explains the “forced” (reversible) elasticity observed in slowly propagating polymeric necks, and also briefly analyses the viscoelastic effects and dissipative heat generation when polymer necks propagate fast enough. Keywords: Necking; Elongation; Semi-crystalline polymers; Propagation speed; Stretch ratio; Forced elasticity 1. Introduction The necking phenomena usually occur when a homogeneous solid polymeric bar (film or filament), with a non-monotonous dependence of axial force S on stretching ratio λ , is stretched uniaxially in the region of S()λ non-monotony. In this case the polymer bar is not deformed homogeneously. Instead, two almost uniform sections occur in the sample: one being nearly equal to its initial thickness and another being considerably thinner in the cross-sectional dimensions. These sections are jointed by a relatively short transition (necking) zone that propagates with a constant speed along the bar as a stepwise wave in the direction of the bar’s thick end (Fig.1).