I-287/Tappan Zee Bridge Corridor: Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Induced Demand: an Urban and Metropolitan Perspective

Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Robert Cervero, Professor Department of City and Regional Planning University of California Berkeley, California E-Mail: [email protected] Paper prepared for Policy Forum: Working Together to Address Induced Demand U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation Eno Transportation Foundation, Incorporated March 2001 Second Revision Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Most studies of induced travel demand have been carried out at a fine to medium grain of analysis – either the project, corridor, county, or metropolitan levels. The focus has been on urban settings since cities and suburbs are where the politics of road investments most dramatically get played out. The problems assigned to induced demand – like the inability to stave off traffic congestion and curb air pollution – are quintessentially urban in nature. This paper reviews, assesses, and critiques the state-of-the-field in studying induced travel demand at metropolitan and sub-metropolitan grains of analysis. Its focus is on empirical and ex post examinations of the induced demand phenomenon as opposed to forecasts or simulations. A meta-analysis is conducted with an eye toward presenting an overall average elasticity estimate of induced demand effects based on the best, most reliable research to date. 1. URBAN HIGHWAYS AND TRAVEL: THE POLICY DEBATE Few contemporary issues in the urban transportation field have elicited such strong reactions and polarized political factions as claims of induced travel demand. Highway critics charge that road improvements provide only ephemeral relief – within a few year’s time, most facilities are back to square one, just as congested as they were prior to the investment. -

New NY Bridge Buffalo and a Licensed Professional Manager As Well As Highway/Transit Project

Representatives of the New York State Thruway Authority will present and discuss the delivery of the largest single contract in state history and its current progress. Topics will include the planning, procurement, design, construction, and contract management of the $3.98-billion Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge over the Hudson River. The westbound bridge of the twin-spanning crossing recently opened to traffic and the second span is on schedule to open next year. Craig Teepell is the New John Kowalski is the NY Bridge project’s Commercial Manager for the NYS Deputy Construc-tion Manager. He has David R. Capobianco is the Design Thruway Authority on the New NY been a part of the bridge replacement Compliance Engineer and Project Bridge project. He is a 1983 civil effort since 2007, having previously Manager for Delivery for the NYS engineering graduate of the SUNY served as NNYB Project Controls Thruway Authority’s New NY Bridge Buffalo and a licensed professional Manager as well as Highway/Transit Project. Dave managed the concurrent engineering New York. John formerly Engineering Manager for the Tappan development of the Environmental was employed by the NYS Department Zee Bridge/I-287 Corridor Project. Prior Impact Statement and the Design-Build of Transportation for 30 years where he to joining the NYS Thruway Authority, procurement documents including the held a number of positions in bridge Craig was part of the NYS Department of technical evaluation of proposals and design and construction in the Buffalo Transportation Major Projects group. selection process. Prior to his region, and served as Deputy Project Craig also con-tributed to the involvement in the Tappan Zee Bridge Director for the Route 9A Reconstruc- reconstruction of Lower Manhattan as replacement, Dave held positions as the tion project in Lower Manhattan Engineering Coordinator for the Route Director of Structural Design and following the 9/11 attacks. -

The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Real Estate Papers Wharton Faculty Research 10-2011 The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Gilles Duranton University of Pennsylvania Matthew A. Turner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Duranton, G., & Turner, M. A. (2011). The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities. American Economic Review, 101 (6), 2616-2652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Abstract We investigate the effect of lane kilometers of roads on vehicle-kilometers traveled (VKT) in US cities. VKT increases proportionately to roadway lane kilometers for interstate highways and probably slightly less rapidly for other types of roads. The sources for this extra VKT are increases in driving by current residents, increases in commercial traffic, and migration. Increasing lane kilometers for one type of road diverts little traffic omfr other types of road. We find no evidence that the provision of public transportation affects VKT. We conclude that increased provision of roads or public transit is unlikely to relieve congestion. Disciplines Economics | Real Estate This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 American Economic Review 101 (October 2011): 2616–2652 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 = The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities† By Gilles Duranton and Matthew A. -

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

1. ROUTE 84-GOING EAST OR WEST If Traveling on Route 84-East Or

1. ROUTE 84-GOING EAST OR WEST If traveling on Route 84-East or West-take Exit 10S to Route 9W SOUTH. Once on 9W South, travel south through the city of Newburgh. You will pass several traffic lights until you come to the traffic light located at Broadway, which is the main street passing through the city of Newburgh. At the intersection with Broadway, go straight to the next light and continue straight past Sacred Heart Church on your left and Sacred Heart School on your right. At the second light (beyond Broadway, at the corner of Sacred Heart Church) make a right at the traffic light onto Washington Street. Proceed down Washington Street to the next traffic light Turn left at the light and make an immediate right into the parking lot at Independent Living, Inc., which is on the corner beyond the light. There are green awnings on the store fronts of the building. BE VERY CAREFUL MAKING THIS RIGHT HAND TURN. People do not expect you to turn suddenly. 2. NEW YORK STATE THRU-WAY (ROUTE 87-NORTH OR SOUTH) Traveling on the New York State Thruway (ROUTE 87-North or South), get off at Exit 17-which is Newburgh/Route 300 After paying toll, follow signs for Route 300 South. (Make a right at the light onto Route 300.) At third light (See a Nissan Dealer ahead), make a left on to Route 17K. Proceed down Route 17K through the city of Newburgh. (Route 17K becomes Broadway.) At the seventh traffic light on Route 17K/Broadway, make a right turn on to Lake Street (Route 32 South). -

Barge Canal” Is No Longer an Accurate Description of the New York State Canals Marine Activity on New York’S Canals

The Story of the Afterword Today, the name “Barge Canal” is no longer an accurate description of the New York State Canals marine activity on New York’s canals. Trains and trucks have taken over the transport of most cargo that once moved on barges along the canals, but the canals remain a viable waterway for navigation. Now, pleasure boats, tour Historical and Commercial Information boats, cruise ships, canoes and kayaks comprise the majority of vessels that ply the waters of the legendary Erie and the Champlain, Oswego and Cayuga- Seneca canals, which now constitute the 524-mile New York State Canal ROY G. FINCH System. State Engineer and Surveyor While the barges now are few, this network of inland waterways is a popular tourism destination each year for thousands of pleasure boaters as well as visitors by land, who follow the historic trade route that made New York the “Empire State.” Across the canal corridor, dozens of historic sites, museums and community festivals in charming port towns and bustling cities invite visitors to step back in time and re-live the early canal days when “hoggees” guided mule-drawn packet boats along the narrow towpaths. Today, many of the towpaths have been transformed into Canalway Trail segments, extending over 220 miles for the enjoyment of outdoor enthusiasts from near and far who walk, bike and hike through scenic and historic canal areas. In 1992, legislation was enacted in New York State which changed the name of the Barge Canal to the “New York State Canal System” and transferred responsibility for operation and maintenance of the Canal System from the New York State Department of Transportation to the New York State Canal Corporation, a newly created subsidiary of the New York State Thruway Authority. -

Effective Strategies for Congestion Management

EFFECTIVE PRACTICES FOR CONGESTION MANAGEMENT: FINAL REPORT Requested by: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Prepared by: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Cambridge, MA Resource Systems Group, Inc. Burlington, VT November 2008 The information contained in this report was prepared as part of NCHRP Project 20-24(63), National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board. Acknowledgements This study was requested by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and conducted as part of National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Project 20-24. The NCHRP is supported by annual voluntary contributions from the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs). Project 20-24 is intended to fund studies of interest to the leadership of AASHTO and its member DOTs. Christopher Porter of Cambridge Systematics was the lead author of the report, working with John Suhrbier of Cambridge Systematics and Peter Plumeau and Erica Campbell of Resource Systems Group. The work was guided by a task group chaired by Constance Sorrell which included Daniela Bremmer, Mara Campbell, Ken De Crescenzo, Eric Kalivoda, Ronald Kirby, Sheila Moore, Michael Morris, Janet Oakley, Gerald Ross, Steve Simmons, Dick Smith, Kevin Thibault, Mary Lynn Tischer, and Robert Zerrillo. The project was managed by Andrew C. Lemer, Ph. D., NCHRP Senior Program Officer. Disclaimer The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied are those of the research agency that performed the research and are not necessarily those of the Trans- portation Research Board or its sponsors. The information contained in this document was taken directly from the submission of the author(s). This docu- ment is not a report of the Transportation Research Board or of the National Research Council. -

New York State Canal Corporation: Infrastructure Inspection And

New York State Office of the State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli Division of State Government Accountability Infrastructure Inspection and Maintenance New York State Canal Corporation Report 2014-S-45 May 2015 2014-S-45 Executive Summary Purpose To determine whether the New York State Canal Corporation’s (Corporation) inspection scheduling procedures ensure that all high- and intermediate-importance structures are periodically inspected and whether inspection results are considered when maintenance activities are prioritized. The audit covers the period January 2012 through October 2014. Background The Corporation, a subsidiary of the New York State Thruway Authority (Thruway Authority), was created in 1992 to operate and maintain the New York State Canal System (Canal System). The Canal Law requires the Corporation to maintain the Canal System in good condition. The Corporation’s Canal Structure Inspection Manual-95 has established inspection requirements and frequency standards, including in-depth inspections (Inspections) – both above and below water – of structural safety and integrity on a 2-year cycle. Of the 2,065 structures the Corporation is required to inspect, 747 are deemed “critical” (e.g., dams and locks). Key Findings • While the Corporation does perform routine operational and reliability checks of the Canal System’s critical structures, it has not performed the two-year Inspections of a significant number of these structures. In fact, some structures that the Corporation’s infrastructure management system identifies as critical have not had an Inspection in many years – and some not at all. • The Corporation’s process for determining Inspection and maintenance priorities is inconsistent, and the basis for decisions is sometimes unclear. -

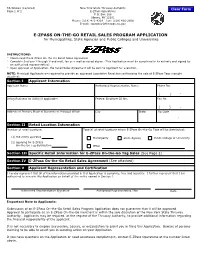

TA-W6333: E-Zpass On-The-Go Retail Sales Program Application For

TA-W6333 (12/2014) New York State Thruway Authority Page 1 of 2 E-ZPass Operations P.O. Box 189 Albany, NY 12201 Phone: (518) 471-4218 Fax: (518) 436-2808 E-mail: [email protected] E-ZPASS ON-THE-GO RETAIL SALES PROGRAM APPLICATION for Municipalities, State Agencies and Public Colleges and Universities ® INSTRUCTIONS: • Please read the E-ZPass On-the-Go Retail Sales Agreement. • Complete Sections I through V and mail, fax or e-mail as noted above. (This Application must be completed in its entirety and signed by an authorized representative). • Upon approval of Application, the Retail Sales Agreement will be sent to Applicant for execution. NOTE: Municipal Applicants are required to provide an approved Legislative Resolution authorizing the sale of E-ZPass Tags (sample attached). Section I Applicant Information Applicant Name Authorized Representative Name Phone No. ( ) - Doing Business As (DBA)(if applicable) Federal Employer ID No. Fax No. ( ) - Address of Primary Place of Business or Principal Office City State Zip Code - Section II Retail Location Information Number of retail locations: Type(s) of retail locations where E-ZPass On-the-Go Tags will be distributed: (1) the entity operates Municipality State Agency Public College or University (2) applying for E-ZPass On-the-Go Tag distribution Other Section III Specific Retail Information for E-ZPass On-the-Go Tag Sales (See Page 2) Section IV E-ZPass On-the-Go Retail Sales Agreement (See attached) Section V Applicant Representation and Certification I hereby represent that all of the information provided in this Application is complete, true and accurate. -

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development final memorandum prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 www.camsys.com final technical memorandum Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Technical Memorandum for Task 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Need.................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 The National Policy Imperative .......................................................................... -

Driving Directions to Westchester Medical Center

Driving Directions to Westchester Medical Center By Car Taconic Parkway SOUTH to Sprain Brook Parkway to Medical Center exit (just past New York State Police Headquarters). Make right at top of exit onto Route 100 (south). Follow to entrance to Medical Center grounds on right. Route 684 SOUTH to Saw Mill River Parkway to Sprain Brook Parkway to Medical Center exit (just past New York State Police Headquarters). Make right at top of exit onto Route 100 (south). Follow to entrance to Medical Center grounds on right. Saw Mill River Parkway SOUTH to Sprain Brook Parkway to Medical Center exit (just past New York State Police Headquarters). Make right at top of exit onto Route 100 (south). Follow to entrance to Medical Center grounds on right. Saw Mill River Parkway NORTH to 1-287 east to Exit 4 (Route 100A north, which becomes Route 100 north). 3.2 miles from exit to entrance to Medical Center grounds on left. I-87 (New York State Thruway) SOUTH to Tappan Zee Bridge. I-287 east to Exit 4 (Route 100A north, which becomes Route 100 north). 3.2 miles from exit to entrance to Medical Center grounds on left. I-87 (New York State Thruway) NORTH to 1-287 east to Exit 4 (Route 100A north, which becomes Route 100 north). 3.2 miles from exit to entrance to Medical Center grounds on left. Sprain Brook Parkway NORTH to Medical Center exit. Make left onto Medical Center grounds. I-95 (New England Thruway) NORTH or SOUTH to 1-287 west (Cross Westchester Expressway). -

M:(7/95):Thruway Defined for Highway Use Tax Purposes:Tsbm956m

New York State Department of Taxation and Finance TSB-M-95 (6)M Taxpayer Services Division Highway Use Tax Technical Services Bureau July 15, 1995 (This replaces TSB-M 95(6)M with a print date of June 1, 1995, which should be destroyed) Thruway Defined for Highway Use Tax Purposes The Highway Use Tax Law (Article 21 of the New York State Tax Law) imposes a weight-distance tax on miles traveled on New York State public highways by certain motor vehicles. In imposing the tax it provides different tax treatment for toll-paid Thruway mileage than for other New York travel. This memorandum defines the portion of the New York State public highway system comprising The Governor Thomas E. Dewey New York State Thruway (Thruway). It also describes the portion of the system considered toll-paid Thruway for purposes of the Highway Use Tax Law. The toll-paid portion of the Thruway consists of parts of several interstate highways running through New York State. This portion of the Thruway includes: • Interstate Route 95 (I-95) from the Bruckner Expressway interchange in the Bronx north to the Connecticut state line, • 1-87 from the New York City/Yonkers city line north to exit 24 at Albany, • The connection from exit 21-A of 1-87 at Selkirk east to exit B- 1 of 1-90, then on to the Massachusetts state line (Berkshire Section) (I-90 from exit 24 at Albany east to exit B-1 of the Berkshire Section is not part of the Thruway system.), • 1-90 from exit 24 at Albany west to the Pennsylvania state line, • 1-190 from exit 53 of 1-90 north to the Robert Moses Parkway, and • The Garden State Parkway Connection from exit 14-A of 1-87 at Spring Valley south to the New Jersey state line.