Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at the University of Maryland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibolster Defense Miami's Status Extend Streaks

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D C. •• MONDAY, A-19 San Francisco, JANUARY », 1056 wM wl Dayton Seek to ¦y * V, -C5jH _ Wi Jgg - ' H I :lIPIHIK &#*& ¦\. ¦T Mprepp* 0 My (<J»*sMF£vW* •¦ :ilW^H^nMMaaMMMBMMHHHBHMv'SIW: w**W ¦F, —i™: >•' *B* «*\l:k '« _ '¦: iaO J^m Extend Streaks B; the Auocltted Preet San Francisco and Dayton,; the mighty among the Nation’s! college basketball teams, should »Ur BBnK. Pl :: have little trouble extending their unbeaten streaks this week. But don’t bet on it. Particularly after the hectic action over the week end. during which four of the top 10 teams—- M Lr I including second -ranked North! Carolina State were beaten.! m, The Wolfpack, after 23 straight n k k s t successes, dropped a 68-58 deci- lxft m MHHw . sion to Duke. San Francisco has two games on tap this week and if they win! both the top-rated Dons willi equal the collegiate record for; consecutive victories at 39. Bill 1 Russell and Co. have won II this year and 37 straight over the ¦$ ~ \ jg/A last three years. ’' Santa Improved It '¦ Clara V JMI Santa Clara tomorrow night; and Fresno State Friday night will be the Dons’ opponents. Al- though neither is expected to TATUM FAMILY HEADED SOUTH—Coach Jim versity of North Carolina. Left to right are: Becky, spring the big surprise, it's a GAME Tatum of Maryland tells his family that they are 10; Jim, jr., 8; Tatum; Reid, 3, and Mrs. Tatum, matter of record that Santa, BRUINS LOST THIS FIGHT AND THE Park for Clara, by Feerick, DETROlT.—Officials George Hayes (left) and Bill Morrison (center) attempt leaving College Chapel Hill, N. -

The University of Maryland

2008-09 30 WRESTLING THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UNIVERSITY SYSTEM It has earned a national reputation for its enriched educational These programs are guided by outstanding faculty whose OF MARYLAND deeP roots, experiences for undergraduates, including such widely imitated accomplishments in research abound. Whether the issue is William Kirwan Chancellor Irwin Goldstein Sr. Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs BROAD IMPACT living/learning programs as College Park Scholars; Gemstone, Mideast peace, cutting-edge research in nanoscience, homeland Joseph A. Vivona C.O.O. and Vice Chancellor for Charles Benedict Calvert founded the Maryland Agricultural a unique program that brings teams of students together from security or bioscience advances, Maryland faculty are selected Administration and Finance College in 1856 with the goal of creating a school that would across disciplines to tackle specific technical problems; and the for national leadership and are making news. Many recent major Leonard Raley Vice Chancellor for Advancement offer outstanding practical knowledge to him and his neighbors Hinman CEO Entrepreneurship Program, sponsored jointly by faculty initiatives receiving significant external support strengthen and be “an institution superior to any other.” the A. James Clark School of Engineering and the Robert H. our homeland security endeavors—centers for research on UNIVERSITY One hundred and fifty years later, the University of Maryland Smith School of Business, and widely recognized as the most agrosecurity and emergency management; intermodal freight has blossomed from its roots as the state’s first agricultural successful student entrepreneurship program in the nation. transportation security; behavioral and social analyses of ADMINISTRATION college and one of America’s original land grant institutions terrorism and responses to terrorism; astrophysics and advanced C.D. -

Virginia Cavaliers Maryland Terrapins

GAME 6 • OCT. 12, 2013 • VIRGINIA AT MARYLAND • BYRD STADIUM (51,802) • COLLEGE PARK, MD. ATHLETICS MEDIA RELATIONS Asst. AD for Media Relations (coach interviews): Jim Daves O: (434) 243-2467 • C: (434) 962-7668 • [email protected] Football Contact (player interviews): Vincent Briedis O: (434) 982-5533 • C: (434) 362-3792 • [email protected] ON THE WEB: VirginiaSports.com VIRGINIA ON TWITTER: @UVA_Football • #UVAFB 7 COLLEGE FOOTBALL HALL OF FAMERS • 3 NFL HALL OF FAMERS • 27 FIRST-TEAM ALL-AMERICANS • 114 FIRST-TEAM ALL-ACC HONOREES 2013 SCHEDULE/RESULTS VIRGINIA GAME DETAILS Date Opponent Time/Result TV CAVALIERS Venue Byrd Stadium Aug. 31 BYU W, 19-16 ESPNU Record: 2-3 ACC: 0-1 Capacity 51,802 Sept. 7 No. 2 OREGON L, 10-59 ABC/ESPN2 Playing Surface FieldTurf Sept. 21 VMI W, 49-0 ESPN3 Series vs. UMD: Virginia trails, 32-43-2 Sept. 28 at Pitt* L, 3-14 RSN HEAD COACH: Mike London, fourth season In College Park: Virginia trails, 13-20-2 Oct. 5 BALL STATE L, 27-48 RSN UVa Record: 18-24 • Career Record: 42-29 • Record vs. MD: 1-2 Last Meeting: 2012 (UMD 27, UVa 20) Oct. 12 at Maryland* 3:30 p.m. ESPNU Television ESPNU Oct. 19 DUKE* 3:30 p.m. RSN MARYLAND Oct. 26 GEORGIA TECH1* TBA Radio Virginia Sports Network Nov. 2 No. 3 CLEMSON* TBA TERRAPINS Live Stats VirginiaSports.com Nov. 9 at North Carolina* TBA Record: 4-1 ACC: 0-1 School Websites VirginiaSports.com Nov. 23 at No. 13 Miami (Fla.)* TBA UMTerps.com Nov. -

2017-18 Big Ten Records Book

2017-18 BIG TEN RECORDS BOOK Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten. BIG TEN CONFERENCE RECORDS BOOK 2017-18 70th Edition FALL SPORTS Men’s Cross Country Women’s Cross Country Field Hockey Football* Men’s Soccer Women’s Soccer Volleyball WINTER SPORTS SPRING SPORTS Men's Basketball* Baseball Women's Basketball* Men’s Golf Men’s Gymnastics Women’s Golf Women’s Gymnastics Men's Lacrosse Men's Ice Hockey* Women's Lacrosse Men’s Swimming and Diving Rowing Women’s Swimming and Diving Softball Men’s Indoor Track and Field Men’s Tennis Women’s Indoor Track and Field Women’s Tennis Wrestling Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Women’s Outdoor Track and Field * Records appear in separate publication 4 CONFERENCE PERSONNEL HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Faculty Representatives Basketball Coaches - Men’s 1997-2004 Ron Turner 1896-1989 Henry H. Everett 1906 Elwood Brown 2005-2011 Ron Zook 1898-1899 Jacob K. Shell 1907 F.L. Pinckney 2012-2016 Tim Beckman 1899-1906 Herbert J. Barton 1908 Fletcher Lane 2017- Lovie Smith 1906-1929 George A. Goodenough 1909-1910 H.V. Juul 1929-1936 Alfred C. Callen 1911-1912 T.E. Thompson Golf Coaches - Men’s 1936-1949 Frank E. Richart 1913-1920 Ralph R. Jones 1922-1923 George Davis 1950-1959 Robert B. Browne 1921-1922 Frank J. Winters 1924 Ernest E. Bearg 1959-1968 Leslie A. Bryan 1923-1936 J. Craig Ruby 1925-1928 D.L. Swank 1968-1976 Henry S. Stilwell 1937-1947 Douglas R. Mills 1929-1932 J.H. Utley 1976-1981 William A. -

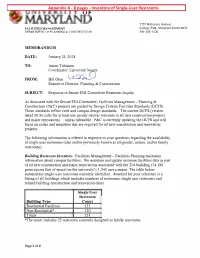

8 Pages - Inventory of Single-User Restrooms OF

Appendix A - 8 pages - Inventory of Single-User Restrooms OF 7757 Baltimore Avenue FACILITIES MANAGEMENT College Park, Maryland 20742-6033 DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING & CONSTRUCTION 301-405-1120 MEMORANDUM DATE: January 24, 2018 TO: Aaron Tobiason Coordinator, University .:,�e FROM: Bill Olen � Executive Director, Planning & Construction SUBJECT: Response to Senate EDI Committee Restroom Inquiry As discussed with the Senate EDI Committee, Facilities Management - Planning & Construction (P&C) projects are guided by Design Criteria Facilities Standards (DCFS). These standards reflectcode and campus design standards. The current DCFS (version dated 2016) calls forat least one gender neutral restroom in all new construction projects and major renovations unless infeasible. P&C is currently updating the DCFS and will focuson codes and mandates that are required forall new construction and renovation projects. The following information is offeredin response to your questions regarding the availability of single user restrooms (also and/or previously known as all�gender, unisex, and/or family restrooms). Building Restroom Inventory: Facilities Management - Facilities Planning maintains information about campus facilities. We maintain and update restroom facilitiesdata as part of all new construction and major renovations associated with the 254 builiding (14.lM gross square feetof space) on the university's 1,340 acre campus. The table below summarizes single-user restrooms currently identified. Attached foryour referenceis a listing of all buildings -

The #1 Way to Reach 48,000 University of Maryland Students, Faculty, and Staff!

THE DIAMONDBACK The #1 way to reach 48,000 University of Maryland students, faculty, and staff! PUBLISHED BY MARYLAND MEDIA INC. 3136 SOUTH CAMPUS DINING HALL COLLEGE PARK, MD 20742 301-314-8000 Contents Who are we? 2018–2019 Publication Schedule Special Sections and Products Orientation Guide Terp Housing Guide Basketball Spirit Papers Print Rates Online Rates Creating Your Ad Checking Ad Size THE DIAMONDBACK 3136 SOUTH CAMPUS DINING HALL, COLLEGE PARK MD 20742 • 301-314-8000 • WWW.DBKNEWS.COM Who Are We? The Diamondback, the University of Maryland’s independent student-run newspaper is published by Maryland Media Inc. – a 501c3 nonprofit. Published continuously since 1910, The Diamondback is College Park’s only newspaper and #1 source for news, sports, and entertainment. We distribute 6,000 newspapers FREE at 68 on and off campus locations, and publish online daily at DBKnews.com. The Diamondback reaches 100,000 readers each week and is regularly recognized for editorial excellence, including being named the #1 college newspaper in the country four times by the Society of Professional Journalists. Address Staff Published by Maryland Media Inc. Editor-in-chief: Ryan Romano 3136 South Campus Dining Hall Advertising Director: Patrick Battista College Park, MD 20742 Business Manager: Craig Mummey 301.314.8000 General Manager: Arnie Applebaum Why Advertise with The Diamondback? Brand Website Increase Recognition Conversions Sales Make your business Advertise on dbknews.com Adding coupons & special known to UMD students to see more people -

SATURDAY APRIL 29 / 10 A.M. to 4 P.M. Inspiration

EXPLORE OUR WORLD OF FEARLESS IDEAS SATURDAY APRIL 29 / 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Inspiration. Boldness. Curiosity. Passion. The University of Maryland’s one-day open house features hundreds of family-friendly and interactive events. Come explore our world of Fearless Ideas and see how we do good for our community, the state and the world. Now in its 19th year, Maryland Day is packed with exciting events and exhibits in six “learning neighborhoods” spread across campus. TERP TOWN CENTER AG DAY AVENUE McKeldin Mall, the Stamp Student Union What began more than 150 years ago as and the surrounding areas become Terp the Maryland Agricultural College has Town Center. Learn about our schools grown into a world-class public research and colleges, catch a special performance institution. Explore Ag Day Avenue to at the main stage and meet the men’s learn why the College of Agriculture and women’s basketball teams. Find and Natural Resources is not just about a bite to eat, and don’t miss the kids’ farming. carnival featuring a rock climbing wall and fun obstacle course. ART & DESIGN PLACE BIZ & SOCIETY HILL Indulge your artistic talents and meet Surround yourself with exhibits in scores of student and faculty performers business, public policy and the social and artists. After taking in performances at sciences, featuring a variety of events the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, for prospective students and parents. head over to the Parren J. Mitchell Art- Explore our world of criminology and Sociology and Architecture buildings to criminal justice in Tydings Hall. -

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content Company & Financial Congressional Transcripts (GROUP FILE Food and Drug Administration Espicom Company Reports (SELECTED ONLY) Veterinarian Newsletter MATERIAL) (GROUP FILE ONLY) Election Weekly (GROUP FILE ONLY) Health and Human Services Department Legal FDCH Transcripts of Political Events Military Review American Bar Association Publications (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Endowment for the Humanities ABA All Journals (GROUP FILE ONLY) General Accounting Office Reports "Humanities" Magazine ABA Antitrust Law Journal (GROUP FILE (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and ONLY) Government Publications (GROUP FILE Alcoholism's Alcohol Research & ABA Banking Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY): Health ONLY) Agriculture Department's Economic National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA ABA Business Lawyer (GROUP FILE Research Service Agricultural Outlook Notes ONLY) Air and Space Power Journal National Institutes of Health ABA Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY) Centers for Disease Control and Naval War College Review ABA Legal Economics from 1/82 & Law Prevention Public Health and the Environment Practice from 1/90 (GROUP FILE ONLY) CIA World Factbook SEC News Digest ABA Quarterly Tax Lawyer (GROUP FILE Customs and Border Protection Today State Department ONLY) Department of Energy Documents The Third Branch ABA The International Lawyer (GROUP Department of Energy's Alternative Fuel U.S. Department of Agricultural FILE ONLY) News Research ABA Tort and Insurance Law Journal Department of Homeland Security U.S. Department of Justice's -

“Standard” It

- SPORTS. THE feVENPro STAB. WASHINGTON . P. C„ THURSDAY. OCTOBER 4. 1928: SPORTS. 35 Powerful Tarheel Eleven to Invade : School Teams in Four Games Tomorrow LEADS TARHEELS Stagg’s New System ST. JOHN’S ELEVEN I College Squads Here in Last TARHEELS TO BRING Includes Deception MARYLAND’SRIVAL SIX D. C. ELEVENS SQUAD OF 32 MEN OPENS OCTOBER 12 Hard Sessions of Week Today y x Zube Sullivan, coach o fthe St. John'd CHAPEL HILL, N. C., October 4. X >X»vY*. x * x College foot ball team, faces a real Job for games Saturday, to kick goal preventing the a light practice for this HIGHLY SHOW WARES preparation Old Liners With scheduled \ ooofcooo to his eleven success-* WED Wm k a IS WILL bring through squads tying. Capital college foot ball were from afternoon, the North Carolina foot ball ful this Fall. Though Ver- to undergo thefr final hard drills campaign Catholic University and American squad of 32 men will leave here tonight mont avenue lads will play the hardest today. Tomorrow will be devoted to history, they have Clash Saturday at College Two of Clashes Are Between INlight tapering-off work. University grldders, who will clash in for College Park, Md., where. on Satur- schedule in their the Brookland Stadium at 2:30 o’clock, day, the Tarheels will engage the Old a squad of only 15 drilling on the Tidal just list of Georgetown, both will be striving for a win follow- Liners in the first conference test of Basin Field and the bunch is about Park Should Be One of Capital Aggregations. -

Ralph Felton

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Ralph Felton This article is by Budd Bailey The phrase “There’s no place like home” is part of American culture because of its use as the final line of the classic movie, “The Wizard of Oz.” Ralph “Rass” Felton certainly believed in that principle, based on how he lived his life. The only interruption in his connection to his hometown came because of football. Once that was done, though, Felton went back where he started to live happily ever after. Ralph Dwain Felton was born on May 21, 1932, in the small town of Midway, Pennsylvania. It had 913 people in it in 2010 and was located west of Pittsburgh. This raises the question, Midway is midway of what? It’s the halfway point of a rail line between Pittsburgh and Steubenville, Ohio. Midway once had its own high school. Ralph has to rank second out of two on the list of famous football graduates from the town. Dick Haley, a player (1959-1964) and a front office executive who is considered one of the great talent scouts in the sport’s history, probably gets top billing for fame. But Felton did quite well for himself too. Ralph was part of a good-sized family. Father Harry and Mother Mary Anna – both of whom were born in Midway - had seven children in all. Ralph’s grandfather William was born in England in 1862 and arrived in the United States in 1885. Grandmother Ann took a similar route. Perhaps their families headed to Western Pennsylvania to find work, and stayed there for the rest of their lives. -

The University of Maryland

60 2008 MARYLAND TRACK & FIELD THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND tional experiences for undergraduates, including such widely These programs are guided by outstanding faculty whose DEEP ROOTS, imitated living/learning programs as College Park Scholars; accomplishments in research abound. Whether the issue is BROAD IMPACT Gemstone, a unique program that brings teams of students Mideast peace, cutting-edge research in nanoscience, home- Charles Benedict Calvert founded the Maryland Agricultural together from across disciplines to tackle specific technical land security or bioscience advances, Maryland faculty are College in 1856 with the goal of creating a school that would problems; and the Hinman CEO Entrepreneurship Program, selected for national leadership and are making news. Many offer outstanding practical knowledge to him and his neighbors sponsored jointly by the A. James Clark School of Engineer- recent major faculty initiatives receiving significant external and be “an institution superior to any other.” ing and the Robert H. Smith School of Business, and widely support strengthen our homeland security endeavors—centers One hundred and fifty years later, the University of Maryland recognized as the most successful student entrepreneurship for research on agrosecurity and emergency management; in- has blossomed from its roots as the state’s first agricultural col- program in the nation. termodal freight transportation security; behavioral and social lege and one of America’s original land grant institutions into a analyses of terrorism and responses to terrorism; astrophysics model of the modern research university. It is the state’s great- and advanced world climate and weather prediction; and a na- est asset for its economic development and its future, and has tional Center for Advanced Study of Language. -

Game Miami #Hoosrising: by the Numbers

MIAMI GAME November 12, 2016 2 p.m. • RSN Charlottesville, Va. Scott Stadium (61,500) 10 #MIAvsUVA BREAKDOWN 2016 SCHEDULE Date: Sat., Nov. 12, 2016 Date Opponent Time /Result TV Location: Charlottesville, Va. S. 3 RICHMOND L, 20-37 ACC Net. Extra Stadium: Scott Stadium (61,500) S. 10 at 24/22 Oregon L, 26-44 ESPN Series vs. Miami: Miami leads, 7-6 VS S. 17 at UConn L, 10-13 ESPN3/SNY In Charlottesville: UVA leads, 4-2 S. 24 CENTRAL MICHIGAN W, 49-35 RSN at Scott Stadium: UVA leads, 4-2 O. 1 at Duke* W, 34-20 ACC Network Last Meeting: 2015 (@Miami, 27-21) O. 15 PITT* L, 31-45 ACC Network First Meeting: 1996 Carquest Bowl (Miami, 31-21) O. 22 22/21 NORTH CAROLINA* L, 14-35 RSN Largest UVA win: 48 (48-0), 2007 O. 29 5/5 LOUISVILLE* L, 25-32 ABC/ESPN2 Longest UVA Win Streak: 3 (2010-12) VIRGINIA CAVALIERS MIAMI HURRICANES N. 5 at Wake Forest* L, 20-27 RSN Record: 2-6, ACC: 1-3 Record: 5-4, ACC: 2-3 Mendenhall vs. Richt: First Meeting Websites: VirginiaSports.com N. 12 MIAMI* 2 p.m. RSN Head Coach: Bronco Mendenhall Head Coach: Mark Richt HurricaneSports.com N. 19 at Georgia Tech* 12:30 p.m. ACC Network UVA Record: 2-7 • first season Miami Record: 5-4 • first season N. 26 at Virginia Tech* TBD Career Record: 101-50 • 12th season Career Record: 146-51 • 16th season Mendenhall vs. Miami: 0-0 Richt vs. UVA: 0-0 All Times Eastern; *ACC game OPENING KICK ON THE AIR SATURDAY IS SENIOR DAY AT SCOTT STADIUM Regional Sports Networks • Saturday is “Senior Day” at Scott Stadium where fourth and Wes Durham, play-by-play fifth years will be honored prior to the game with Miami.