The Thames River Watershed: a Background Study for Nomination Under the Canadian Heritage Rivers System 1 9 9 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

1984 London Majors Program

$1.00 N9 0325 CANADA’S softdrink & 13 London Locations Shoppe to Serve You / 1984 SOUVENIR LONDON LONDON’S LARGEST 30 DIFFERENT WATERBED DEALER STYLES AVAILABLE Open Mon. - Fri. Sat. 10-9 10-6 1478 DUNDAS ST. 555 WELLINGTON RD. In The Eastown Plaza Just South of Commissioners 452-1440 685-3333 Printed by Carter’s Printing Services The Corporation of the City of London The Office of the Mayor Al Gleeson Mayor It gives me great pleasure on behalf of the City of London to extend greetingsand bestwishesto each ofyou as you attend the events of the London Majors. The growing interest and enthusiasm of all in sports and athletics is most heartening Best wishes for an exciting season. Al Gleeson, Mayor FANS: Kids, Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to beautiful Labatt Park. Sit back, relax and enjoy the game and the excellent surroun dings before you. We, the London Majors, would like to take this opportunity to thank Mr. Bob Neskas and Mr. Ted Bogal for their leadership and direction in making this facility available to us. But, folks, there is one man that has taken a personal interest in making this baseball field what it is, “The Best Baseball Diamond in our League” and undoubtedly one of the very best in all Canada. That man is Mr. Mike Regan. The Majors extend to you, Mike, a very special thank you. The London Majors are very appreciative to a man, to the P.U.C., and the City of London and are proud to call Labatt Park home. Enjoy the game. -

Hidden Gems in London and Southwestern Ontario

Hidden Gems in London and Southwestern Ontario Downtown Attractions: Covent Garden Market: A London Museum London: Through public Banting House: Known as “The tradition since1845. Find farm- and educational programming, Birthplace of Insulin.” It is the fresh produce, award-winning special events and exhibitions, house where Sir Frederick Banting meats, local cheese, and more. Museum London strives to pro- woke up at two o’clock in the mote the knowledge and enjoy- morning on October 31, 1920 with ment of regional art, culture and the idea that led to the discovery history. of insulin. Western Fair Market: The Market Eldon House: Virtually unchanged London Music Hall: A premier at Western Fair District is a vibrant since the nineteenth century, stop for many bands/artists gathering place in the heart of Eldon House is London’s oldest as they tour through Southern Old East Village bringing togeth- residence and contains family Ontario. Acts such as The Arkells, er community, food and local heirlooms, furnishings and price- Killswitch Engage, Calvin Harris, artisans. less treasures. Snoop Dogg & many more have played here. Victoria Park: Victoria Park is an The Old East Village lies just east of The London Children’s Museum 18-acre park located in down- London, Ontario’s downtown. A provides children and their grown- town London, Ontario, in Cana- welcoming home to people of nu- ups with extraordinary hands-on da. It is one of the major centres merous backgrounds, our village is learning experiences in a distinctly of community events in London. truly a global village. child-centred environment. -

The Thames River, Ontario

The Thames River, Ontario Canadian Heritage Rivers System Ten Year Monitoring Report 2000-2012 Prepared for the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Prepared by Cathy Quinlan, Upper Thames River Conservation Authority March, 2013 ISBN 1-894329-12-0 Upper Thames River Conservation Authority 1424 Clarke Road London, Ontario N5V 5B9 Phone: 519-451-2800 Website: www.thamesriver.on.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cover Photograph: The Thames CHRS plaque at the Forks in London. C. Quinlan Photo Credits: C. Quinlan, M. Troughton, P. Donnelly Thames River, Ontario Canadian Heritage Rivers System, Ten Year Monitoring Report 2000 – 2012 Compiled by Cathy Quinlan, Upper Thames River Conservation Authority, with assistance from members of the Thames Canadian Heritage River Committee. Thanks are extended to the CHRS for the financial support to complete this ten year monitoring report. Thanks to Andrea McNeil of Parks Canada and Jenny Fay of MNR for guidance and support. Chronological Events Natural Heritage Values 2000-2012 Cultural Heritage Values Recreational Values Thames River Integrity Guidelines Executive Summary Executive Summary The Thames River nomination for inclusion in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) was accepted by the CHRS Board in 1997. The nomination document was produced by the Thames River Coordinating Committee, a volunteer group of individuals and agency representatives, supported by the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority (UTRCA) and Lower Thames Valley Conservation Authority (LTVCA). The Thames River and its watershed were nominated on the basis of their significant human heritage features and recreational values. Although the Thames River possesses an outstanding natural heritage which contributes to its human heritage and recreational values, CHRS integrity guidelines precluded nomination of the Thames based on natural heritage values because of the presence of impoundments. -

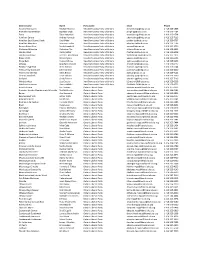

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Appendix A-3 Part 3 Archaeological Built Heritage Reports

Appendix A-3 Part 3 Archaeological Built Heritage Reports REPORT Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Springbank Dam and "Back to the River" Schedule B Municipal Class Environmental Assessment, City of London, Ontario Submitted to: Ashley Rammeloo, M.M.Sc., P.Eng, Division Manager, Engineering Rapid Transit Implementation Office Environmental & Engineering Services City of London 300 Dufferin Avenue London, Ontario N6A 4L9 Golder Associates Ltd. 309 Exeter Road, Unit #1 London, Ontario, N6L 1C1 Canada +1 519 652 0099 1772930-5001-R01 April 24, 2019 April 24, 2019 1772930-5001-R01 Distribution List 1 e-copy: City of London 1 e-copy: Golder Associates Ltd. Project Personnel Project Director Hugh Daechsel, M.A., Principal, Senior Archaeologist Project Manager Michael Teal, M.A., Senior Archaeologist Task Manager Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA, Senior Cultural Heritage Specialist Research Lindsay Dales, M.A., Archaeologist Robyn Lacy, M.A., Cultural Heritage Specialist Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA Field Investigations Robyn Lacy, M.A. Report Production Robyn Lacy, M.A. Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA Elizabeth Cushing, M.Pl., Cultural Heritage Specialist Mapping & Illustrations Zachary Bush, GIS Technician Senior Review Bradley Drouin, M.A., Associate, Senior Archaeologist i April 24, 2019 1772930-5001-R01 Executive Summary The Executive Summary highlights key points from the report only; for complete information and findings, as well as the limitations, the reader should examine the complete report. Background & Study Purpose In May 2017, CH2M Hill Canada Ltd. (now Jacobs Engineering Group) retained Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) on behalf of the Corporation of the City of London (the City), to conduct a cultural heritage overview for the One River Master Plan Environmental Assessment (EA). -

What Was the Iroquois Confederacy?

04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 82 What was the 4 Iroquois Confederacy? Chapter Focus Questions •What was the social structure of Iroquois society? •What opportunities did people have to participate in decision making? •What were the ideas behind the government of the Iroquois Confederacy? The last chapter explored the government of ancient Athens. This chapter explores another government with deep roots in history: the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois Confederacy formed hundreds of years ago in North America — long before Europeans first arrived here. The structure and principles of its government influenced the government that the United States eventually established. The Confederacy united five, and later six, separate nations. It had clear rules and procedures for making decisions through representatives and consensus. It reflected respect for diversity and a belief in the equality of people. Pause The image on the side of this page represents the Iroquois Confederacy and its five original member nations. It is a symbol as old as the Confederacy itself. Why do you think this symbol is still honoured in Iroquois society? 82 04 AB6 Ch 4.11 4/2/08 11:22 AM Page 83 What are we learning in this chapter? Iroquois versus Haudenosaunee This chapter explores the social structure of Iroquois There are two names for society, which showed particular respect for women and the Iroquois people today: for people of other cultures. Iroquois (ear-o-kwa) and Haudenosaunee It also explores the structure and processes of Iroquois (how-den-o-show-nee). government. Think back to Chapter 3, where you saw how Iroquois is a name that the social structure of ancient Athens determined the way dates from the fur trade people participated in its government. -

Site Considerations Report

Pendleton Solar Energy Centre Site Considerations Report Prepared for: EDF EN Canada Development Inc. 53 Jarvis Street, Suite 300 Toronto ON M5C 2H2 Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Ltd. Suite 1 – 70 Southgate Drive Guelph ON N1G 4P5 File No. 160950781 June 18, 2015 PENDLETON SOLAR ENERGY CENTRE SITE CONSIDERATIONS REPORT Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... I 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1.1 2.0 METHODS .....................................................................................................................2.1 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................3.1 3.1 3.2.6 (A) MTCS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES CONFIRMATION ...................................... 3.1 3.2 3.2.6 (B) SITE CONSIDERATIONS INFORMATION .......................................................... 3.1 4.0 CLOSURE ......................................................................................................................4.1 5.0 REFERENCES .................................................................................................................5.1 LIST OF TABLES Table 3.1: Site and Connection Point Approximate Coordinates .............................. 3.1 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix A: Site Considerations Mapping Appendix B: Site Considerations Concordance -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

Mcintosh Gallery a Driving Force: Women of the London, Ontario, Visual Arts Community, 1867 to the Present

McIntosh Gallery A Driving Force: Women of the London, Ontario, Visual Arts Community, 1867 to the Present Elsie P. Williams and London, Ontario's First Permanent Art Gallery Luvneet K. Rana Sources Armstrong, Fredrick Henry. The Forest City: An Illustrated History of London, Canada. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, Ltd., 1986. Baker, Michael and Hilary Bates Neary, eds. 100 Fascinating Londoners. Toronto, Ontario: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers, 2005. Baker, Michael and Hilary Bates Neary, eds. London Street Names: An Illustrated Guide. Toronto, Ontario: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers, 2003. Bank of Canada. Inflation Calculator. Accessed Feb.26, 2020. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator. Bentley, Susan. Elsie's Estate: The Life, Love, and Legacy of Elsie Perrin Williams. London, Ontario: M&T Printing of London Ontario, 2018. Brown, Vanessa and Jason Dickson. London: 150 Cultural Moments. Windsor: Biblioasis, 2017. “Dr. Hadley T. Williams, Faculty of Medicine, Tenure 1900-1931.” The University of Western Ontario Archives and Research Collection Centre Virtual Exhibit: History of Medicine. Accessed February 10, 2018. https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/historyofmedicine/Faculty/williams.html. Geddes Poole, Nancy. The Art of London, 1830-1980. London, Ontario: Blackpool Press, 1984. E-Book published by Nancy Geddes Poole, 2017. “Elsie Perrin Williams Memorial Library.” Canada’s Historic Places. Accessed January 5, 2018. http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=11193. “Elsie Perrin Williams Estate.” Canada’s Historic Places. Accessed February 10, 2018. http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=11032 “Obituaries.” Journal of the Canadian Medical Association (April 1932): p. -

Things to Do in London During Canadian Beef Industry Conference

THINGS TO DO IN LONDON DURING CANADIAN BEEF INDUSTRY CONFERENCE RAINY DAY ACTIVITIES FOR FAMILIES & ADULTS The Factory –Opening May 2018 Address: 100 Kellogg Ln., London | Email: [email protected] | www.thefactorylondon.ca We have an impressive 160,000 square feet and we want to fill every last inch with endless fun for the whole family. High ropes, zip-lines, trampoline park, ultimate warrior course, arcade, kid's soft play, laser tag, virtual reality, escape rooms, brewery and more - these attractions are all in the plans for The Factory and are catered to all ages and skill levels. We won't just cater to the adventurous: we will have a restaurant, a lounge area with Wifi and comfortable parent zones so you can sit back and relax or get some work done while your kids test their skills on the ropes course. The Rec Room – Opening May 2018 Address: 1680 Richmond St., London | http://www.therecroom.com/default/promo/nowhiring-london Are you ready to play at London’s biggest, shiniest new playground? Get pumped because The Rec Room is opening soon! We’re bringing some serious fun & games to Masonville Place and we can’t wait to welcome you! The Rec Room redefines the meaning of fun with over 36,000 sq. feet of great games, mouth-watering eats and amazing entertainment, all packed under one roof! The Rec Room is the place to let go, be playful and experience something new and exciting. We’re Canada’s premier “eats & entertainment” hotspot, and we’re taking London by storm!With Canadian-inspired cuisine, virtual reality, arcades games, live entertainment, and more, The Rec Room is the ultimate gathering place to grab a pint, host an event, or just play. -

1958 Council

LONDON FREE PRESS CHRONO. INDEX Date Photographer Description 1/1/58 B. Smith New Year's Babies at Victoria and St. Josephs Hospital Wildgust New Year's baby, St. Mary with baby boy - First New Years Baby in Chatham - Sarnia's New Year baby Wildgust Stratford...Children with tobaggans on hills K. Smith Annual mess tour K. Smith Bishop Luxton holds open house B. Smith Mr. and Mrs. C. J. Donnelly and attendants celebrate 50th wedding anniversary Blumson Barn Fire at Ingersoll 2/1/58 Blumson Officers installed at the North London Kiwanis Club at the Knotty Pine Inn J. Graham Collecting old Xmas trees J. Graham Lineup at License Bureau; Talbot Street Cantelon Wingham...First new years baby at Goderich Wildgust Stratford...New year baby to Mrs. Bruce Heinbuck Stratford K. Smith St. Peters towers go up Blumson Used Cars at London Motors Products J. Graham PUC inaugural PUC offices in City Hall 3/1/58 Burnett Snow storm Richmond at Dundas - Woodstock...Oxford farmer set up brucellosis control area J. Graham Goderich...Alexandria Marine Hospital Blumson Skiers take advantage of recent snowfall at the London Ski 1 LONDON FREE PRESS CHRONO. INDEX Date Photographer Description Club Cantelon first New Years baby Palmerston General Hospital K. Smith tobacco men meet at Mount Brydges Blumson Fred Dickson who prepares and builds violins and other string instruments Burnett London Twshp council inaugural 4/1/58 Blumson Fire at 145 Chesterfield St. J. Graham Mrs Conrons, Travellers aid at CNR Retires K. Smith Mustangs vs Bowling Green; Basketball B. Smith annual junior instruction classes at London Ski Club - fire burn Christmas tree in city dumps 5/1/58 Blumson Ice on the Thames River - Chatham...Ice fishing Mitchell's Bay J.