Boarding Injuries: the Long and the Short of It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cristian Bota 3Socf5x9eyz6

Cristian Bota https://www.facebook.com/index.php?lh=Ac- _3sOcf5X9eyz6 Das Imperium Talent Agency Berlin (D.I.T.A.) Georg Georgi Phone: +49 151 6195 7519 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dasimperium.com © b Information Acting age 25 - 35 years Nationality Romanian Year of birth 1992 (29 years) Languages English: fluent Height (cm) 180 Romanian: native-language Weight (in kg) 68 French: medium Eye color green Dialects Resita dialect: only when Hair color Brown required Hair length Medium English: only when required Stature athletic-muscular Accents Romanian: only when required Place of residence Bucharest Instruments Piano: professional Cities I could work in Europe, Asia, America Sport Acrobatics, Aerial yoga, Aerobics, Aikido, Alpine skiing, American football, Archery, Artistic cycling, Artistic gymnastics, Athletics, Backpacking, Badminton, Ballet, Baseball, Basketball, Beach volleyball, Biathlon, Billiards, BMX, Body building, Bodyboarding, Bouldering, Bowling, Boxing, Bujinkan, Bungee, Bycicle racing, Canoe/Kayak, Capoeira, Caster board, Cheerleading, Chinese martial arts, Climb, Cricket, Cross-country skiing, Crossbow shooting, CrossFit, Curling, Dancesport, Darts, Decathlon, Discus throw, Diving, Diving (apnea), Diving (bottle), Dressage, Eskrima/Kali, Fencing (sports), Fencing (stage), Figure skating, Finswimming, Fishing, Fistball, Fitness, Floor Exercise, Fly fishing, Free Climbing, Frisbee, Gliding, Golf, Gymnastics, Gymnastics, Hammer throw, Handball, Hang- Vita Cristian Bota by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-05-10 -

Snowboard Manual

Snowboard Manual Your guide to teaching & riding from beginner to advanced Snowboard Instruction New Zealand (a division of NZSIA) PO Box 2283, Wakatipu, Queenstown, New Zealand. www.nzsia.org Editorial Written by Paul Phillip, Leo Carey and Keith Stubbs. Additional contributions from Sam Smith, Tony Macri, Claire Dooney, Rhys Jones and Elaine Tseng. Edited by Keith Stubbs and Alex Kerr. Imagery Front cover: Nick Hyne and Stef Zeestraten taken by Vaughan Brookfield. Inside spread: Nick Hyne taken by Vaughan Brookfield. Teaching photography by Kahli Hindmarsh. Sequence images and technical riding from Rhys Jones, Richie Johnston, Tony Macri, Paul Phillip and Freddie Bacon; all shot and edited by Keith Stubbs. Additional photography from Ricky Otaki, Richie Johnston and Cardrona Alpine Resort. Design by Loz Ferguson from Pop Creative. Printing by Print Central. A huge thank you to all past SBINZ Examiners. You have all been a huge part in making SBINZ what it is today. © 2017 SBINZ / NZSIA. All Rights Reserved. Preface Snowboard Instruction New Zealand is responsible for the education and certification for snowboard instructing throughout New Zealand. First established in 1992 under a different name, SBINZ quickly joined with the New Zealand Ski Instructors’ Association to create the New Zealand Snowsports Instructors’ Alliance (NZSIA). SBINZ is one of the four divisions within the NZSIA and has become an internationally-recognised educational body that is renowned for producing professional, knowledgeable instructors, with the capabilities to teach and ride at very high standards. Driven by a Course Manager and a Technical Committee, the Snowboard Division is responsible for all snowboard course content and delivery, and the direction of snowboard teaching and coaching throughout New Zealand. -

Wintergreen Adaptive Sports Fact Sheet

About WAS Wintergreen Adaptive Sports ("WAS") is a chapter of Disabled Sports USA and is a 501(c)3 non-profit located at Wintergreen Resort in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Central Virginia. Established in 1995, WAS provides adaptive sport instruction in skiing, snowboarding, kayaking, canoeing and golf to students with a wide range of physical and cognitive disabilities. WAS operates seven days a week during the ski season from mid-December to mid-March. During the summer, WAS offers adaptive canoeing and kayaking instruction on various weekends from June to mid- September. Additionally, WAS conducts a mid-summer golf tournament for Wounded Warriors at Kingsmill Resort in Williamsburg, VA. WAS is governed by a 12-member board of directors. A full-time executive director oversees WAS day- to-day operations which are led by a staff of seven part-time seasonal employees. Instruction is offered by approximately 130 volunteers, most of whom are certified by PSIA (skiing), AASI (snowboard); or ACA (canoeing and kayaking). History Established in 1995 and now the largest adaptive snow sports program serving the Mid-Atlantic, WAS provides trained volunteer instructors as well as standard and adaptive ski and snowboard and paddling equipment to people with a wide range of disabilities. Through its program of adaptive sport instruction, WAS offers the therapeutic results of exercise – physical, emotional, and psychological – as well as friendship, inspiration, and encouragement to individuals with a disability, their families and caregivers. WAS has just completed its 20th year of operation. It has grown steadily over the years to where it now has over 95 volunteer snow sport instructors and over 30 water sport instructors. -

Businessplan

BUSINESSPLAN von Simone Melda und Melanie Ruff RUFFBOARDS Sportartikel GmbH Hofstattgasse 4/1 A-1180 Wien Office: +43 680 230 60 71 Mail: [email protected] Web: http://ruffboards.com Wien, Februar 2015 RUFFBOARDS BUSINESSPLAN Februar 2015 Table of content 1_EXECUTIVE SUMMERY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2_ The IDEA ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 3_ INNOVATION....................................................................................................................................................... 9 4_ The PRODUCT ................................................................................................................................................... 10 5_ The RUFF-TEAM ................................................................................................................................................ 15 5_SPORTS-MARKET................................................................................................................................................ 17 6_ FUTURE AMBITIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 18 2 RUFFBOARDS BUSINESSPLAN Februar 2015 1_EXECUTIVE SUMMERY RUFFBOARDS produces uniquely designed, high-end longboards (skateboards) by upcycling used -

Snowboard, Ski, and Skateboard Sensor System Application Adrien Doiron Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Mechanical Engineering Senior Theses Engineering Senior Theses 12-15-2014 Snowboard, Ski, and Skateboard Sensor System Application Adrien Doiron Santa Clara University Michael Fernandez Santa Clara University Victor Ojeda Santa Clara University Robert Ross Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/mech_senior Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Doiron, Adrien; Fernandez, Michael; Ojeda, Victor; and Ross, Robert, "Snowboard, Ski, and Skateboard Sensor System Application" (2014). Mechanical Engineering Senior Theses. 42. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/mech_senior/42 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering Senior Theses at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mechanical Engineering Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Snowboard, Ski, and Skateboard Sensor System Application by Adrien Doiron, Michael Fernandez, Victor Ojeda, Robert Ross SENIOR DESIGN PROJECT REPORT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical or Electrical Engineering School of Engineering Santa Clara University Santa Clara, California December 15, 2014 Snowboard, Ski, and Skateboard Sensor System Application Adrien Doiron, Michael Fernandez, Victor Ojeda, Robert Ross Departments of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering Santa Clara University 2014 ABSTRACT The goal of this project was develop a sensor for the commercial market for skiers, snowboarders, and skateboarders that can give them the data such as speed, elevation, pressure, temperature, flex, acceleration, position, and other performance data such as trick characterization. This was done by using a variety of sensors, including a GPS, flex sensors, accelerometer, and others to provide data such as speed, position, position, and temperature. -

Kayak Rental Bellingham Kayak Rental Seattle Kayak Rental BC

Kayak Rental Bellingham Aquatica Outdoor Recreation Co. Pacifica Paddlesports 19C South Shore Rd 789 Saunders Lane Community Boating Center Lake Cowichan, BC V0R 3E1 Brentwood Bay, Victoria, BC 555 Harris Ave 250-745-3804 250-665-7411 Bellingham, WA (360) 714-8891 Wilderness Kayak & Adventure Co Salty’s Adventure Sports 6683 Beaumont Ave 1057 Roberts Creek Rd Kayak Rental Seattle Maple Bay, Duncan, BC Roberts Creek, BC V0N 3A7 250-746-0151 604-741-8635 Alki Adventure Center 1660 Harbor Ave SW Bennett Bay Kayaking Sea to Sky Kayak Center #3 West Seattle, WA 98126 Bennett Bay, Mayne Island, BC 123 Charles St (206) 953-0237 250-539-0864 North Vancouver, BC V7H 1S1 604-983-6663 Ballard Kayak Rental Andale Kayak Rentals Shilshole Bay Marina, I-dock 1484 North Beach Rd Bowen Island Kayaking 7001 Seaview Ave NW Salt Spring Island, BC V8K 1B2 Snug Cove, Bowen Island, BC Seattle, WA 98117 250-537-0700 or 250-889-9867 604-947-9266 TF 1-800-605-2925 (206) 494-3353 Victoria Kayak Ecomarine Ocean Kayak Centre Moss Bay Kayak Rental 1006 Wharf Street 1668 Duranleau, Granville Island, 1001 Fairview Ave N. Victoria, BC V8W 1T4 Vancouver, BC V6H 3S4 Seattle, WA 98109 250-216-5646 604-689-7575 TF 1-888-425-2925 (206) 682-2031 Northern Wave Kayak Inc. Western Canoeing & Kayaking Kayak Rental BC 2071 Malaview Ave 1717 Salton Rd Box 115 West Sidney, BC V8L 5X6 Abbotsford, BC V2S 4N8 Comox Valley Kayaks 250-655-7192 604-853-9320 TF 1-866-644-8111 2020 Cliffe Ave Courtenay, BC V9N 2L3 Ocean River Sports Pedals and Padels TF 1-888-545-5595 1824 Store Street Sechelt, -

Skiing & Snowboarding Safety

Center for Injury Research and Policy The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital Skiing & Snowboarding Safety Skiing and snowboarding are great ways to spend time outdoors during the winter months. As with all sports, injuries are a risk when you ski or snowboard. Taking a few safety measures can help you have fun and be safe. Skiing & Snowboarding Injury Facts Skiing & Snowboarding Safety Tips • Bruises and broken bones are the most common • Always wear a helmet designed for skiing or types of skiing- and snowboarding injuries. snowboarding. • Snowboarders most commonly injure their wrist • Protect your skin and eyes from the sun and and arm. Skiers most commonly injure their wind. Apply sunscreen and wear ski goggles that knee, head or face. fit properly with a helmet. • Most ski and snowboarding injuries occur during • Make sure your boots fit properly and bindings a fall or a crash (usually into a tree). are adjusted correctly. • Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of • Prepare for the weather. Wear layers of clothes serious injuries among skiers and snowboarders and a helmet liner, a hat or a headband. and is also the most common cause of death. • Do not ski or snowboard alone. • Follow all trail rules. • Stay on the designated trails. Recommended Equipment • Only go on trails that match your skill level. • Helmet designed for skiing and snowboarding • Take a lesson – even experienced skiers and • Goggles that fit over a helmet snowboarders can benefit from a review. • Properly fitted boots and bindings • Before using a ski lift, tow rope or carpet, make • Sunscreen sure you know how to get on, ride and get off • Wrist guards for snowboarders safely. -

Sly Fox Ski and Snowboard Club Participate in CMSC Trips and the Trips of Other Member Clubs

SKI. RELAX. REPEAT. At Aspen Square, we know the key essentials for a great vacation – ideal location, comfortable well-appointed accommodations, friendly assistance when you need it. So relax – we’ve got you covered! INDIVIDUAL. WELCOMING. UNFORGETTABLE. 101 unique condominiums. Full hotel-style services and amenities. At the base of Aspen Mountain. 1.800.862.7736 | aspensquarehotel.com EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING Publisher - CMSC Mike Thomas [email protected] Editor - Rick Heinz About cMSc [email protected] The Chicago Metropolitan Ski Council (CMSC) is an association of 67 member clubs which offer downhill and nordic skiing, boarding and year- round activities. We are adventure clubs, Design & Production single clubs, family clubs, and clubs that welcome all comers. SKI. Rick Drew & Karola Wessler [email protected] CMSC, founded in 1957, is managed entirely by volunteers who are members of our clubs. RELAX. Our publication, the Ski & Ride Club Guide, and our website provide information on Club and Advertising Sales - Mike Thomas Council activities. Our aim is to promote skiing and boarding. [email protected] REPEAT. CMSC member clubs have trips planned to almost every major destination in North-America Chicago Metropolitan Ski Council and Europe at various times throughout the year. Please visit their website to learn more PO Box 189 about them and their activities. At Aspen Square, we know the key Wood Dale, IL 60191-0189 SkiCMSC.com essentials for a great vacation – ideal location, comfortable well-appointed content accommodations, friendly assistance when you need it. ABOUT THIS MAGAZINE So relax – we’ve got you covered! Ski & Ride Club Guide is published annually, and is the official publication of the Chicago Metropolitan Ski Council (CMSC). -

The Potential for Speed © 2018 the Regents of the University of California

Using spring stilts, people can bounce very high and run very fast. potential energy, which is stored energy. By The Potential adding a force to the mix, these two types of energy can be converted back and forth— motion energy can become stored energy, and stored energy can become motion energy. For for Speed extreme athletes, that conversion usually means speed, height, or both! To learn more about how Chapter 1: Introduction energy and force make these exciting things possible, read one of the chapters that follow. Can you fly through the air? Can you zoom down a snowy mountain at 80 kilometers per hour (50 miles per hour)? With a little extra equipment and some practice, you probably © 2018 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Permission granted to purchaser to photocopy for classroom use. Image Credit: GeoffTompkinson/Photographer’s Choice/Getty Images. can: extreme sports allow us to do exhilarating things our bodies can’t do on their own. To get the speed and height we like so much, these sports rely on two kinds of energy—kinetic energy, which is the energy of motion, and The Potential for Speed The Potential for Speed 1 2 The Potential for Speed The Potential for Speed © 2018 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Permission granted to purchaser to photocopy for classroom use. Chapter 2: Snowboarding Is there any bigger thrill than weaving down a mountain on a snowboard? The world record for speed on a snowboard is a whopping 203 kilometers per hour (126 miles per hour), and advanced snowboarders regularly reach speeds of 65-70 kph (40-45 mph) to launch themselves high into the air off ramps in the snow. -

The International Ski Competition Rules (Icr)

THE INTERNATIONAL SKI COMPETITION RULES (ICR) BOOK II CROSS-COUNTRY APPROVED BY THE 51ST INTERNATIONAL SKI CONGRESS, COSTA NAVARINO (GRE) EDITION MAY 2018 INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE SKI INTERNATIONALER SKI VERBAND Blochstrasse 2; CH- 3653 Oberhofen / Thunersee; Switzerland Telephone: +41 (33) 244 61 61 Fax: +41 (33) 244 61 71 Website: www.fis-ski.com ________________________________________________________________________ All rights reserved. Copyright: International Ski Federation FIS, Oberhofen, Switzerland, 2018. Oberhofen, May 2018 Table of Contents 1st Section 200 Joint Regulations for all Competitions ................................................... 3 201 Classification and Types of Competitions ................................................... 3 202 FIS Calendar .............................................................................................. 5 203 Licence to participate in FIS Races (FIS Licence) ...................................... 7 204 Qualification of Competitors ....................................................................... 8 205 Competitors Obligations and Rights ........................................................... 9 206 Advertising and Sponsorship .................................................................... 10 207 Competition Equipment and Commercial Markings .................................. 12 208 Exploitation of Electronic Media Rights .................................................... 13 209 Film Rights .............................................................................................. -

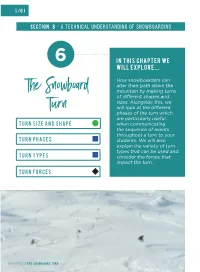

Section B (A Technical Understanding of Snowboarding)

B/01 Section b - A Technical Understanding of Snowboarding 6 In this chapter we will explore... How snowboarders can alter their path down the The Snowboard mountain by making turns of different shapes and sizes. Alongside this, we will look at the different Turn phases of the turn which are particularly useful Turn Size and Shape when communicating the sequence of events throughout a turn to your Turn phases students. We will also explain the variety of turn types that can be used and Turn types consider the forces that impact the turn. Turn forces CHAPTER 6 / THE SNOWBOARD TURN B/02 Turn Size and Shape Put simply, the longer the board spends in the fall line or the more gradually a rider applies movements, the larger the turn becomes. When we define the size of the turn we consider the length and radius of the arc: small, medium or large. The size of your turn will vary depending on terrain, snow conditions and the type of turn you choose to make. SMALL MEDIUM LARGE A rider’s rate of descent down the mountain is controlled mainly by the shape of their turns relative to the fall line. The shape of these turns can be described as open (unfinished) and closed (finished). A closed turn is where the rider completes the turn across the hill, steering the snowboard perpendicular to the fall line. This type of turn will easily allow the rider to control both their forward momentum and rate of descent. Closed turns are used on steeper pitches, or firmer snow conditions, to keep forward momentum down. -

US Ski & Snowboard COVID-19 Cross Country Ski

U.S. Ski & Snowboard COVID-19 Cross Country Ski Domestic Competitions Guidance v1.1: September 29, 2020 Page 1 COVID-19 Cross Country Ski Strategic Planning Commission Members Chair: Bryan Fish (U.S. Ski & Snowboard) Medical: Troy Taylor and Gillian Bower (U.S. Ski & Snowboard) Legal: Alison Pitt (U.S. Ski & Snowboard) Officials: Allan Serrano (FIS NA TD Commissioner) Working Group: COVID-19 Cross Country Ski National Domestic Competition Working Group (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1PZj83AsAoGTusUhUe65UizpAuFIrYh5tkdJMYxkxFiE /edit?pli=1#gid=341894714 Goals ● Provide guidance and direction for hosting cross country ski races during the COVID-19 pandemic ● Help to minimize the risk and spread of COVID-19 infection at U.S. Ski & Snowboard races ○ U.S. Ski & Snowboard to provide best practice direction on physical distancing as well as; forms for clubs/teams to manage pre-screen questionnaires and daily symptom checks ○ Compliance with local health authority mandates and diligence in hosting events gives everyone the best opportunity to avoid cancelations ○ Partner with our host venues for hosting cross country ski races I. Introduction U.S. Ski & Snowboard is committed to assisting all members, clubs, volunteers and competition organizers navigate the upcoming 2020-21 domestic competition season as impacted by the COVID-19 global pandemic. We recognize that COVID-19 has impacted different parts of the country in different ways and with different timing. COVID-19 is extremely contagious and is believed to spread mainly from person-to-person contact and can lead to severe illness and death. All U.S. Ski & Snowboard members and participants are expected to follow all local, state and federal public health mandates during competition participation.