Exploring Post-Military Geographies: Plymouth and the Spatialities of Armed Forces Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 655 28 February 2019 No. 261 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 28 February 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 497 28 FEBRUARY 2019 498 Stephen Barclay: As the shadow spokesman, the right House of Commons hon. and learned Member for Holborn and St Pancras (Keir Starmer), said yesterday,there have been discussions between the respective Front Benches. I agree with him Thursday 28 February 2019 that it is right that we do not go into the details of those discussions on the Floor of the House, but there have The House met at half-past Nine o’clock been discussions and I think that that is welcome. Both the Chair of the Select Committee, the right hon. Member for Leeds Central (Hilary Benn) and other distinguished PRAYERS Members, such as the right hon. Member for Birkenhead (Frank Field), noted in the debate yesterday that there had been progress. It is important that we continue to [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] have those discussions, but that those of us on the Government Benches stand by our manifesto commitments in respect of not being part of a EU customs union. BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS 21. [909508] Luke Pollard (Plymouth, Sutton and NEW WRIT Devonport) (Lab/Co-op): I have heard from people Ordered, from Plymouth living in the rest of the EU who are sick I beg to move that Mr Speaker do issue his Warrant to the to the stomach with worry about what will happen to Clerk of the Crown to make out a New Writ for the electing of a them in the event of a no deal. -

Key Findings and Actions from the One Number Census Quality Assurance Process

Census 2001 Key findings and actions from the One Number Census Quality Assurance process 1 Contents Page 1 Introduction 3 2 Overview and summary 3 2.1 The One Number Census process 3 2.2 Imputation summary 4 2.3 Overview of the ONC Quality Assurance process 5 3 Key findings from the Quality Assurance process 5 3.1 Detailed findings identified from the Quality Assurance process 5 3.1.1 1991 Under-enumeration adjustments 6 3.1.2 London investigation 6 3.1.3 Babies in areas with large ethnic populations 18 3.1.4 Post stratification 19 4 Investigations resulting in adjustments 19 4.1 Contingency measures 19 4.1.1 Collapsing strata 20 4.1.2 Borrowing strength 20 4.1.3 Borrowing strength for babies 22 4.2 Population subgroup analyses 22 4.2.1 Full time students 23 4.2.2 Home Armed Forces personnel 24 4.2.3 FAF personnel 25 4.2.4 Prisoners 25 5 Dependency 26 6 Response rates 27 7 Further analysis and findings resulting from the quality assurance process 30 7.1 Comparisons with administrative and demographic data used in the Quality Assurance Process 30 7.1.1 Comparison with administrative sources 30 7.1.2 Comparison with MYEs 31 7.1.3 Sex ratios 35 8 Conclusion 36 References 37 Annex A: Glossary of acronyms 38 Annex B: Household and person imputation analysis 39 Annex C: Matrix of key themes and findings 42 Annex D: HtC levels and age-sex groups collapsed by Design Group 57 Annex F: LADs that received student halls of residence adjustments 70 Annex G: Defence communal establishments that received an adjustment for undercount among the armed forces 71 2 Key findings and actions from the One Number Census Quality Assurance process 1 Introduction Finally there is a section that outlines the 1.1 The aim of this report is to provide 2001 dependency adjustment made to the ONC Census users with a detailed insight into the key estimates. -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

Plymouth in World War I 2

KS2/3 HISTORY RESOURCE PLYMOUTH IN WORLD WAR I 2 CONTENTS 3 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE 4 PLYMOUTH IN WORLD WAR I IMAGES FROM THE COLLECTION 8 1914: DISRUPTION TO LOCAL SCHOOLS 10 1915: MILITARY IN THE CITY 12 1916: CONSCRIPTION AND CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS 14 1917: BORLASE SMART 16 1918: THE END OF THE WAR ACTIVITIES 18 THROW OF THE DICE 19 WAR POETRY 20 TEACHER AMBASSADORS 3 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE This resource features the story of the The Box, Plymouth is a major redevelopment amalgamation of the Three Towns of scheme and a symbol for the city’s current Plymouth, Devonport and East Stonehouse regeneration and future. in 1914; reflecting on them as home to the Royal Navy, Army Garrisons, Royal Marines It will be a museum for the 21st century with and Royal Naval Air Service. extrordinary gallery displays, high profile artists and art exhibitions, as well as exciting events and It also looks at the impact of World War I on performances that take visitors on a journey from local people’s lives – touching on recruitment, pre-history to the present and beyond. conscription, the fighting, the cost, the aftermath and the ‘home front’. This is not just a standard review of the First World War from start to finish. It’s the story of Plymouth and Plymothians from 1914 to 1918. All images © Plymouth City Council (The Box) 4 PLYMOUTH IN WORLD WAR I Three Towns Defence of the Realm The modern day City of Plymouth has largely The ‘Three Towns’ had long been closely grown out of three once separate neighbouring associated with the military. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 652 14 January 2019 No. 233 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 14 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 787 14 JANUARY 2019 788 Stewart Malcolm McDonald (Glasgow South) (SNP): House of Commons As the doyenne of British nuclear history, Lord Hennessy, observed recently, the current Vanguard life extension plans are a Monday 14 January 2019 “technological leap in the dark”, which also means there is little room for flexibility in the The House met at half-past Two o’clock overhaul and procurement cycle if CASD is to be maintained with two submarines in 2033-34. What discussions has the Secretary of State had in his Department PRAYERS about contingencies around the Vanguard-to-Dreadnought transition, which we know were discussed during the previous transition to Vanguard? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Gavin Williamson: We constantly have discussions right across Government to make sure that our continuous at-sea nuclear deterrence can be sustained. We have Oral Answers to Questions been investing in technology and parts to make sure that the Vanguard class has everything it needs in the future. But what is critical is the investment we are making: we announced earlier this year an additional DEFENCE £400 million of investment in the Dreadnought class to make sure that is delivered on time and to budget. The Secretary of State was asked— Stewart Malcolm McDonald: But I am afraid to say Vanguard-class Life Extension Programme that, as the misery of the modernising defence programme has shown all of us, the Secretary of State’s Department has much less latitude with large projects than he would 1. -

Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the Uk Chapter of the Electronic Warfare and Information Operations Association (Aoc) Held on Line, Ending 17 March 2020

MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE UK CHAPTER OF THE ELECTRONIC WARFARE AND INFORMATION OPERATIONS ASSOCIATION (AOC) HELD ON LINE, ENDING 17 MARCH 2020 Because of the corona virus outbreak, it was decided by the Board of Directors (BOD) to hold the AGM on line. Present on line: Wg Cdr John Clifford OBE President Mr Chris Howe MBE Vice President, Awards & Webmaster Mr Ian Fish Membership Secretary Wg Cdr John Stubbington Treasurer Wg Cdr Roger Hannaford Secretary Mr Jonathan (Swaz) Bramley Non-exe Wg Cdr Phil Davies Non-exec Mr Jim MacCulloch Non-exec Mr Darren Nicholls Non-exec Mr David Peck Non-exec Dr Sue Robertson Non-exec, Visits Coordinator Prof David Stupples Non-exec Academic Director ITEM 1. PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS. 1. John Clifford gave his Presidents address. He said that the UK BOD had previously had online meetings and decided to cancel the 2020 AGM because of the risks posed by Coronavirus, as the Board’s first priority was the safety of members. Instead, all the usual reports would be sent to members. 2. Both 2019 and 2020 had been excellent years for the Chapter, having been awarded an 8th consecutive Chapter of the Year award in the large chapter category. This was particularly impressive record being nationally based rather than is the case in the US of being focused on one city, military base or university campus. 3. Membership stood at around 570, with a significant proportion of younger members as will be seen from the Membership Director, Ian Fish’s, report. 4. The Chapter was in a good position financially – see Treasurer John Stubbington’s report. -

{DOWNLOAD} 3 Commando Brigade Pdf Free Download

3 COMMANDO BRIGADE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ewen Southby-Tailyour | 320 pages | 16 Jun 2009 | Ebury Publishing | 9780091926960 | English | London, United Kingdom 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron - Wikipedia Moreman, Tim British Commandos — Battle Orders. Southby-Tailyour, Ewen Ebury Press. Neillands, Robin British Commando Forces as of British Commando units of the Second World War. Royal Naval Commandos British commando frogmen. Royal Air Force Commandos. Her Majesty's Naval Service. Royal Marines. Categories :. Cancel Save. Cap Badge of the Royal Marines. United Kingdom. Marines Commando Light infantry. HQ - Stonehouse Barracks , Plymouth. Apart from during the Falkands War, when the whole squadron was involved, it operated mostly on individual flight detachments. In , 3 Commando Brigade was withdrawn from Singapore. Two further Lynx AH1 joined the Squadron some time later. Its helicopters flew a total of 2, hours in just over three weeks reflecting a remarkable rate of serviceability and flying. Landings started on 21 May under the codename Operation Sutton. Lieutenant Ken D Francis RM and his crewman, Lance Corporal Brett Giffin set off in Gazelle XX to search for them, but were hit by ground fire from a heavy machine gun and were killed instantly, the aircraft crashing on a hillside. Only Candlish survived. The bodies were recovered to SS Canberra, and when that ship was ordered to leave the Falklands and head for South Georgia, Evans, Francis and Giffin were buried at sea in a special service attended by many on board the liner. The REME technicians were able to repair the damage whilst still under constant air attack by Argentinian 'Skyhawk' and 'Mirage' ground attack jets but returned the aircraft for operational use. -

The Royal Marines Impact Report 2019

RMA – THE ROYAL MARINES CHARITY, IMPACT REPORT 2019 www.rma-trmc.org IMPACT REPORT Photograph by anthonyupton.com MAKING A BIG IMPACT RMA – The Royal Marines Charity is a Charity registered in England & Wales (1134205) and Scotland (SC048185) and is a charitable Company Limited by Guarantee (07142012) PAGE 1 RMA – THE ROYAL MARINES CHARITY, IMPACT REPORT 2019 www.rma-trmc.org RMA – THE ROYAL MARINES CHARITY, IMPACT REPORT 2019 www.rma-trmc.org WELCOME: WELCOME GENERAL SIR GORDON MESSENGER KCB DSO* OBE “The Royal PATRON The UK is a maritime nation through necessity, These current operations coupled with the large through the simple fact of our being an island. This number of Marines injured physically or mentally makes our dependence on the oceans staggering – in more distant campaigns who continue to fight 95% of all our imports come by sea. So our country loss and injury on a daily basis with their families, relies on free movement through the seas for our leave us as a nation with a duty to help wherever the prosperity, but also to guarantee our liberty, and Government is unable, alongside those veterans who Marines are therefore we need a strong Navy. have left the service, and also the serving Corps and The Royal Marines have been the Royal their families who carry the daily burden of constant Navy’s own soldiers since 1664, and since they operations and disruption. were assigned responsibility for the Commando I am proud that RMA – The Royal Marines role following the Second World War have been the Charity is there to provide the safety net, a clear UK’s elite amphibious forces, putting into practice demonstration that we are committed to supporting the Commando Spirit and Mindset which sees their our own at their time of need, reaching every facet ethos of courage, determination, unselfishness and cheerfulness in the face of adversity borne out as of the Corps and directly underpinning the Military currently deployed Covenant between our nation and its Armed Forces. -

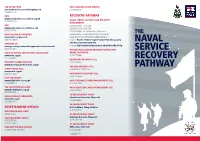

Naval Service Recovery Pathway

THE RIPPLE POND HMS CALEDONIA NRIO (NORTH) www.juliamolony.co.uk/theripplepond 01383 858243 07968 310329 RMA RECOVERY PATHWAY www.royalmarinesassociation.org.uk NAVAL SERVICE CASUALTY AND RECOVERY 02392 651519 MANAGEMENT RNA 02392 628682 – SO1 CRM www.royal-naval-association.co.uk 02392 628730 – SO2 CRM 02392 723747 02392 628684 – Royal Navy Case Conferences THE WHITE ENSIGN ASSOCIATION 02392 628952 – Royal Marines Case Conferences www.whiteensign.co.uk Email: [email protected] 020 7407 8658 Intranet: Via the ‘Helm’ People Portal: PFCS: NS casualty NAVAL VETERANS UK and Recovery Management www.gov.uk/government/organisations/veterans-uk Internet: http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/welfare/fi nd-help 0808 1914218 HASLER NAVAL SERVICE RECOVERY CENTRE (HMS SERVICE REGULAR FORCES EMPLOYMENT ASSOCIATION DRAKE, PLYMOUTH) www.rfea.org.uk 01752 555366 01212 360058 RECOVERY DEVONPORT RECOVERY CELL RECOVERY CAREER SERVICES 01752 555431 www.recoverycareerservices.org.uk FASLANE RECOVERY CELL PATHWAY SSAFA FORCES HELP 01436 674321 EXT 6133 www.ssafa.org.uk 08457 314880 PORTSMOUTH RECOVERY CELL 02392 720609 HELP FOR HEROES www.helpforheroes.org.uk RNAS CULDROSE CAREER MANAGEMENT CELL 01980 844224 01326 552357 THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGION RNSA YEOVILTON CAREER MANAGEMENT CELL www.britishlegion.org.uk 01935 455393 0808 8028080 30 CDO RECOVERY TROOP NAVAL FAMILIES FEDERATION Stonehouse Barracks, Plymouth www.nff.org.uk 01752 836987 02392 654374 40 CDO RECOVERY TROOP RESETTLEMENT OFFICES Norton Manor Camp, Taunton 01823 362518 HMS NELSON NRIO (EAST) 02392 724127 42 CDO RECOVERY TROOP HMS DRAKE NRIO (WEST) Bickleigh Barracks, Plymouth 01752 555300 01752 727299 01752 555362 45 CDO RECOVERY TROOP HMS NEPTUNE NRIO (NORTH) RM Condor, Arbroath 01436 674321 EXT 3594 01241 822231 navygraphics 15/917 The Naval Service Recovery Pathway (NSRP) is part of the Defence Recovery small or big an injury or severe an illness, family support plays a vital Capability and is the process followed to deliver a conducive military role. -

All Approved Premises

All Approved Premises Local Authority Name District Name and Telephone Number Name Address Telephone BARKING AND DAGENHAM BARKING AND DAGENHAM 0208 227 3666 EASTBURY MANOR HOUSE EASTBURY SQUARE, BARKING, 1G11 9SN 0208 227 3666 THE CITY PAVILION COLLIER ROW ROAD, COLLIER ROW, ROMFORD, RM5 2BH 020 8924 4000 WOODLANDS WOODLAND HOUSE, RAINHAM ROAD NORTH, DAGENHAM 0208 270 4744 ESSEX, RM10 7ER BARNET BARNET 020 8346 7812 AVENUE HOUSE 17 EAST END ROAD, FINCHLEY, N3 3QP 020 8346 7812 CAVENDISH BANQUETING SUITE THE HYDE, EDGWARE ROAD, COLINDALE, NW9 5AE 0208 205 5012 CLAYTON CROWN HOTEL 142-152 CRICKLEWOOD BROADWAY, CRICKLEWOOD 020 8452 4175 LONDON, NW2 3ED FINCHLEY GOLF CLUB NETHER COURT, FRITH LANE, MILL HILL, NW7 1PU 020 8346 5086 HENDON HALL HOTEL ASHLEY LANE, HENDON, NW4 1HF 0208 203 3341 HENDON TOWN HALL THE BURROUGHS, HENDON, NW4 4BG 020 83592000 PALM HOTEL 64-76 HENDON WAY, LONDON, NW2 2NL 020 8455 5220 THE ADAM AND EVE THE RIDGEWAY, MILL HILL, LONDON, NW7 1RL 020 8959 1553 THE HAVEN BISTRO AND BAR 1363 HIGH ROAD, WHETSTONE, N20 9LN 020 8445 7419 THE MILL HILL COUNTRY CLUB BURTONHOLE LANE, NW7 1AS 02085889651 THE QUADRANGLE MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY, HENDON CAMPUS, HENDON 020 8359 2000 NW4 4BT BARNSLEY BARNSLEY 01226 309955 ARDSLEY HOUSE HOTEL DONCASTER ROAD, ARDSLEY, BARNSLEY, S71 5EH 01226 309955 BARNSLEY FOOTBALL CLUB GROVE STREET, BARNSLEY, S71 1ET 01226 211 555 BOCCELLI`S 81 GRANGE LANE, BARNSLEY, S71 5QF 01226 891297 BURNTWOOD COURT HOTEL COMMON ROAD, BRIERLEY, BARNSLEY, S72 9ET 01226 711123 CANNON HALL MUSEUM BARKHOUSE LANE, CAWTHORNE, -

Plymouth City Council

(DIP0023) Supplementary written evidence submitted by Plymouth City Council Further to the Panel 1 session of the Defence Committee inquiry on the 08 September 2020, please find provided additional information from Plymouth City Council with respect to the following: Q117 Stuart Anderson: ...Could you explain relatively briefly how you have managed with past fluctuations and what contingency preparations you are making for the integrated review? Being home to the largest naval base in Western Europe, Plymouth has often found itself faced with rumours of cuts to platforms and personnel. Most notably of the recent examples was the rumoured decommissioning of HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark. The city managed the potential consequences of this by quickly convening key partners across the city, commissioned consultants to investigate the economic impacts of the decision and coordinating the Fly the Flag campaign. In partnership with local media outlets, the campaign sought to raise awareness of the potential impacts among the local public and inspire citywide pride and awareness of the contributions of HMNB and Dockyard Devonport to the defence of the realm. The research commissioned established that the ships (HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark) directly employs 968 FTE workers, representing 8 per cent of the total HMNB and Dockyard employment. At the time of writing it was anticipated that these jobs would continue until the mid- 2030s and support an additional temporary uplift of circa 250 workers during two planned upkeep periods of 2-3 years. The contribution of the FTEs directly employed to work on these ships support £52m in GVA in Plymouth. -

1976-1986 General

HEADING RELATED Year Year/pages Abbreviations 1979 List 1979/233 Abbreviations 1981 List 1981/314 Abbreviations 1984 List (A - L) (M - Z) 1984/276, 436 Abseiling 1979 From BBC TV Centre 1979/197* From Telecon Tower (World Abseiling 1985 Record) 1985/248* See also Traffic Accidents Accidents 1982 Mortar Comnb Explosion - killed 3 1982/134 See also Spean Spean Bridge Remembrance Achnacarry Bridge Service 1976/63 Achnacarry 1980 45 Cdo at Spoean Bridge 1980266* Achnacarry 1986 Mrs Pearce researching 1986/203 Peter White - Head of Security at Aden the Embassy 1986/51 Gen Harman visits 40 Cdo in Adjutant General 1976 Northern Ireland 1976/268 Adjutants Article - "Adjutant's Dream" 1985/235 Admiral Commanding Rear Admiral Holins at Marine Reserves Cadet Corps (21 years) 1976/292* Admiral Commanding Title Lapsed on 1 Jan 1977 (DCI Reserves RN565/76 Adventure Article - Outdoor Inactivities Training (Higginson) 19+F87278/286 Adventure Training 40 Cdo on River Pym 1981/267* Adventure Training Cdo Log Regt in Scillies 1981/348* Adventure Training 40 Cdo Adventure Training 1982/162* AFNORTH Maj Gen Hardy appointed COS 1984/140 Agila, Operation See Rhodesia Air Accidents Lt G R Mills RMR - killed 1979/67 Air Days 42 Cdo at Culdrose 1976/338 Air Defence Troop Operationally deployed in Fleet 1984/140 Air Defence Troop Article by Capt P B Simmonds 1984/157* Air Defence Troop Still deployed in Fleet 1985/280 41 (Salerno) Cdo Coy move into Air Force, Royal RAF RAF Luqa 1977/272 Air Force, Royal RAF Regiment Article - History by Sgt H Foxley 1980/100 Sgt