Surface Foraging in Scapanus Moles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Mammal Populations in Riparian Zones of Different-Aged Coniferous Forests

SMALL MAMMAL POPULATIONS IN RIPARIAN ZONES OF DIFFERENT-AGED CONIFEROUS FORESTS R. G. ANTHONY, E. D. FORSMAN, G. A. GREEN, G. WITMER, AND S. K. NELSON ABSTRACT— Small mammals were trapped in riparian zones in young, mature, and old-growth coniferous forests during spring and summer of 1983. Peromyscus manicu- latus was the most abundant species and comprised 76% and 83% of the total captures during spring and summer, respectively. More species, but fewer individuals, were captured on the streamside transects in comparison to the riparian fringe transects, which were 15-20 m from the stream. Six species of Insectivora, including five species of Sorex, were captured in these riparian zones. No species was solely dependent on riparian zones in old-growth forests; however, additional studies are needed to define the specific habitat requirements of Sorex bendirii, Sorex palustris, Neurotrichus gibbsii, Phenacomys albipes, and Microtus richardsoni. Riparian zones recently have been recognized for their uniqueness and intrinsic value as wildlife habitat. To date, much attention has been focused on the most conspicuous riparian zones, such as those found in semiarid lands or along major rivers and streams (Johnson and Jones 1977, Thomas et al. 1979). Studies on wildlife populations in riparian zones dominated by coniferous forests are less numerous (Swanson et al. 1982), although riparian zones along low-order (second-, third-, and fourth-order streams at the head of watersheds) mountain streams are an integral part of the forest ecosystem (Swanson et al. 1982). Harvest of old-growth forests has become a major forestry-wildlife issue, because these forests provide unique wildlife habitat and they are rapidly being logged (Meslow et al. -

Revision of the Mole Genus Mogera (Mammalia: Lipotyphla: Talpidae)

Systematics and Biodiversity 5 (2): 223–240 Issued 25 May 2007 doi:10.1017/S1477200006002271 Printed in the United Kingdom C The Natural History Museum Shin-ichiro Kawada1, 6 , Akio Shinohara2 , Shuji Revision of the mole genus Mogera Kobayashi3 , Masashi Harada4 ,Sen-ichiOda1 & (Mammalia: Lipotyphla: Talpidae) Liang-Kong Lin5 ∗ 1Laboratory of Animal from Taiwan Management and Resources, Graduate School of Bio-Agricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8601, Japan Abstract We surveyed the central mountains and southeastern region of Taiwan 2Department of Bio-resources, and collected 11 specimens of a new species of mole, genus Mogera. The specimens Division of Biotechnology, were characterized by a small body size, dark fur, a protruding snout, and a long Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki tail; these characteristics are distinct from those of the Taiwanese lowland mole, 5200, Kihara, Kiyotake, M. insularis (Swinhoe, 1862). A phylogenetic study of morphological, karyological Miyazaki 889-1692, Japan 3Department of Asian Studies, and molecular characters revealed that Taiwanese moles should be classified as two Chukyo Woman’s University, distinctive species: M. insularis from the northern and western lowlands and the new Yokone-cho, Aichi 474-0011, species from the central mountains and the east and south of Taiwan. The skull of Japan 4Laboratory Animal Center, the new species was slender and delicate compared to that of M. insularis. Although Osaka City University Graduate the karyotypes of two species were identical, the genetic distance between them School of Medical School, Osaka, Osaka 545-8585, Japan was sufficient to justify considering each as a separate species. Here, we present a 5Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology, detailed specific description of the new species and discuss the relationship between Department of Life Science, this species and M. -

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 18 September 2014

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 18 September 2014 List of Recent Land Mammals of Mexico, 2014 José Ramírez-Pulido, Noé González-Ruiz, Alfred L. Gardner, and Joaquín Arroyo-Cabrales.0 Front cover: Image of the cover of Nova Plantarvm, Animalivm et Mineralivm Mexicanorvm Historia, by Francisci Hernández et al. (1651), which included the first list of the mammals found in Mexico. Cover image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 List of Recent Land Mammals of Mexico, 2014 JOSÉ RAMÍREZ-PULIDO, NOÉ GONZÁLEZ-RUIZ, ALFRED L. GARDNER, AND JOAQUÍN ARROYO-CABRALES Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2014, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (nsrl.ttu.edu). The authors and the Museum of Texas Tech University hereby grant permission to interested parties to download or print this publication for personal or educational (not for profit) use. Re-publication of any part of this paper in other works is not permitted without prior written permission of the Museum of Texas Tech University. This book was set in Times New Roman and printed on acid-free paper that meets the guidelines for per- manence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed: 18 September 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publications of the Museum of Texas Tech University, Number 63 Series Editor: Robert J. -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

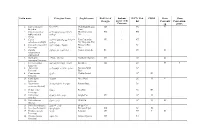

Red List of Endemic IUCN Red CITES Bern Bonn Georgia Species of the List Conventi Convention Caucasus on (CMS) 1

Latin name Georgian Name English name Red List of Endemic IUCN Red CITES Bern Bonn Georgia species of the list Conventi Convention Caucasus on (CMS) 1. Capra aegagrus niamori Wild Goat, Bezoar CR VU II Erxleben. Goat 2. Capra caucasica dasavleTkavkasiuri West Caucasian EN + EN Güldenstädt & jixvi Tur Pallas. 3. Capra aRmosavleTkavkasiuri East Caucasian VU + NT cylindricornis Blyth. jixvi Tur, Dagestan Tur 4. Capreolus capreolus evropuli Sveli European Roe LC Linnaeus. Deer 5. Gazella qurciki, jeirani Goitered Gazelle RE VU II subgutturosa Güldenstädt. 6. Rupicapra arCvi, fsiti Northern Chamois EN LC II rupicapra Linnaeus. 7. Cervus elaphus keTilSobili iremi Red Deer CR LC II I Linnaeus. 8. Sus scrofa gareuli Rori, taxi Eurasian Wild LC Linnaeus. Boar 9. Canis aureus tura Golden Jackal LC III Linnaeus. 10. Canis lupus mgeli Grey Wolf LC II II Linnaeus. 11. Nyctereutes enotisebri ZaRli Racoon Dog LC procyonoides Gray. 12. Vulpes vulpes mela Red Fox LC III Linnaeus. 13. Felis chaus lelianis kata Jungle Cat VU LC II Schreber. 14. Felis silvestris tyis kata Wild Cat LC II II Shreber. 15. Felis libyca Forster. velis kata Steppe Cat 16. Lynx lynx Linnaeus. focxveri Eurasian Lynx CR LC II 17. Panthera pardus jiqi Leopard CR NT I II Linnaeus. 18. Hyaena hyaena afTari Striped Hyaena CR NT Linnaeus. 19. Lutra lutra wavi Eurasian Otter, VU NT I II Linnaeus. Common Otter 20. Martes foina kldis kverna Stone Marten, LC III Erxleben. Beech Marten 21. Martes martes tyis kverna European Pine LC Linnaeus. Marten 22. Meles meles maCvi Eurasian Badger LC Linnaeus. 23. Mustela lutreola waula European Mink EN II Linnaeus. -

Ewa Żurawska-Seta

Tom 59 2010 Numer 1–2 (286–287) Strony 111–123 Ewa Żurawska-sEta Katedra Zoologii Uniwersytet Technologiczno-Przyrodniczy A. Kordeckiego 20, 85-225 Bydgoszcz E-mail: [email protected] kretowate talpidae — ROZMieSZCZeNie oraZ klaSyfikaCja w świetle badań geNetycznyCh i MorfologicznyCh wStęp podział systematyczny ssaków podlega zaproponowanej przez wilson’a i rEEdEr’a ciągłym zmianom, głównie za sprawą dyna- (2005) wyodrębnione zostały nowe rzędy: micznie rozwijających się w ostatnich latach erinaceomorpha, do którego zaliczono je- badań genetycznych. w klasyfikacji owado- żowate erinaceidae oraz Soricomorpha, w żernych insectivora zaszły istotne zmiany. którym znalazły się kretowate talpidae i ry- według tradycyjnej klasyfikacji fenetycznej jówkowate Soricidae. do ostatniego z wymie- kret Talpa europaea linnaeus, 1758, zali- nionych rzędów zaliczono ponadto almiko- czany był do rodziny kretowatych talpidae wate Solenodontidae oraz wymarłą rodzinę i rzędu owadożernych insectivora. do tego Nesophontidae (wcześniej obie te rodziny samego rzędu należały również występujące również zaliczano do insectivora), z zastrze- w polsce jeże i ryjówki. według klasyfikacji żeniem, że oczekiwane są dalsze zmiany. klaSyfikaCja kretowatyCh talpidae rodzina talpidae obejmuje 3 podrodziny: świetnym pływakiem, ponieważ większość Scalopinae, talpinae i Uropsilinae. podrodzi- pożywienia zdobywa na powierzchni wody na Scalopinae podzielona jest na 2 plemiona, oraz w toni wodnej. jest do tego doskona- 5 rodzajów i 7 gatunków (tabela 1). krety z le przystosowany, ponieważ posiada błony tej podrodziny często nazywane są „kretami z pławne między palcami kończyn tylnych. Nowego świata”, ponieważ większość gatun- Ma również długi ogon, stanowiący 75–81% ków występuje w Stanach Zjednoczonych, długości całego ciała, który spełnia rolę ma- północnym Meksyku i w południowej części gazynu tłuszczu, wykorzystywanego głównie kanady. -

Comparative Morphology of the Penis and Clitoris in Four Species of Moles

RESEARCH ARTICLE Comparative Morphology of the Penis and Clitoris in Four Species of Moles (Talpidae) ADRIANE WATKINS SINCLAIR1∗, STEPHEN GLICKMAN2, KENNETH CATANIA3, AKIO SHINOHARA4, LAWRENCE BASKIN1, 1 AND GERALD R. CUNHA 1Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 2Departments of Psychology and Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 3Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 4Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, Kihara, Japan ABSTRACT The penile and clitoral anatomy of four species of Talpid moles (broad-footed, star-nosed, hairy- tailed, and Japanese shrew moles) were investigated to define penile and clitoral anatomy and to examine the relationship of the clitoral anatomy with the presence or absence of ovotestes. The ovotestis contains ovarian tissue and glandular tissue resembling fetal testicular tissue and can produce androgens. The ovotestis is present in star-nosed and hairy-tailed moles, but not in broad-footed and Japanese shrew moles. Using histology, three-dimensional reconstruction, and morphometric analysis, sexual dimorphism was examined with regard to a nine feature mascu- line trait score that included perineal appendage length (prepuce), anogenital distance, and pres- ence/absence of bone. The presence/absence of ovotestes was discordant in all four mole species for sex differentiation features. For many sex differentiation features, discordance with ovotestes was observed in at least one mole species. The degree of concordance with ovotestes was highest for hairy-tailed moles and lowest for broad-footed moles. In relationship to phylogenetic clade, sex differentiation features also did not correlate with the similarity/divergence of the features and presence/absence of ovotestes. -

Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management

Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for the Use of Wildlife Damage Management Methods by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Chapter I Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management MAY 2017 Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services (WS) Program completed Risk Assessments for methods used in wildlife damage management in 1992 (USDA 1997). While those Risk Assessments are still valid, for the most part, the WS Program has expanded programs into different areas of wildlife management and wildlife damage management (WDM) such as work on airports, with feral swine and management of other invasive species, disease surveillance and control. Inherently, these programs have expanded the methods being used. Additionally, research has improved the effectiveness and selectiveness of methods being used and made new tools available. Thus, new methods and strategies will be analyzed in these risk assessments to cover the latest methods being used. The risk assements are being completed in Chapters and will be made available on a website, which can be regularly updated. Similar methods are combined into single risk assessments for efficiency; for example Chapter IV contains all foothold traps being used including standard foothold traps, pole traps, and foot cuffs. The Introduction to Risk Assessments is Chapter I and was completed to give an overall summary of the national WS Program. The methods being used and risks to target and nontarget species, people, pets, and the environment, and the issue of humanenss are discussed in this Chapter. From FY11 to FY15, WS had work tasks associated with 53 different methods being used. -

Lipotyphla: Talpidae: Euroscaptor)

Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS Vol. 320, No. 2, 2016, рр. 193–220 УДК 599.362 (597) SECRETS OF THE UNDERGROUND VIETNAM: AN UNDERESTIMATED SPECIES DIVERSITY OF ASIAN MOLES (LIPOTYPHLA: TALPIDAE: EUROSCAPTOR) E.D. Zemlemerova1, A.A. Bannikova1, V.S. Lebedev2, V.V. Rozhnov3, 5 and A.V. Abramov4, 5* 1Lomonosov Moscow State University, Vorobievy Gory, 119991 Moscow, Russia; e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2Zoological Museum, Moscow State University, B. Nikitskaya 6, 125009 Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 3A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskii pr. 33, Moscow 119071, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 4Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 5Joint Vietnam-Russian Tropical Research and Technological Centre, Nguyen Van Huyen, Nghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam ABSTRACT A study of the Southeast Asian moles of the genus Euroscaptor based on a combined approach, viz. DNA sequence data combined with a multivariate analysis of cranial characters, has revealed a high cryptic diversity of the group. An analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b gene and five nuclear genes has revealed two deeply divergent clades: the western one (E. klossi + E. malayana + E. longirostris from Sichuan + Euroscaptor spp. from northern Vietnam and Yunnan, China), and the eastern one (E. parvidens s.l. + E. subanura). The pattern of genetic variation in the genus Euroscaptor discovered in the present study provides support for the existence of several cryptic lineages that could be treated as distinct species based on their genetic and morphological distinctness and geographical distribution. -

An Evolutionary View on the Japanese Talpids Based on Nucleotide Sequences

Mammal Study 30: S19–S24 (2005) © the Mammalogical Society of Japan An evolutionary view on the Japanese talpids based on nucleotide sequences Akio Shinohara1,*, Kevin L. Campbell2 and Hitoshi Suzuki3 1 Department of Bio-resources, Division of Biotechnology, Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, Miyazaki 889-1692, Japan 2 Department of Zoology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3T 2N2, Canada 3 Graduate School of Environmental Earth Science, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido 060-0810, Japan Abstract. Japanese talpid moles exhibit a remarkable degree of species richness and geographic complexity, and as such, have attracted much research interest by morphologists, cytogeneticists, and molecular phylogeneticists. However, a consensus hypothesis pertaining to the evolutionary history and biogeography of this group remains elusive. Recent phylogenetic studies utilizing nucleotide sequences have provided reasonably consistent branching patterns for Japanese talpids, but have generally suffered from a lack of closely related South-East Asian species for sound biogeographic interpretations. As an initial step in achieving this goal, we constructed phylogenetic trees using publicly accessible mitochondrial and nuclear sequences from seven Japanese taxa, and those of related insular and continental species for which nucleotide data is available. The resultant trees support the view that four lineages (Euroscaptor mizura, Mogera tokuade species group [M. tokudae and M. etigo], M. imaizumii, and M. wogura) migrated separately, and in this order, from the continental Asian mainland to Japan. The close relationship of M. tokudae and M. etigo suggests these lineages diverged recently through a vicariant event between Sado Island and Echigo plain. The origin of the two endemic lineages of Japanese shrew-moles, Urotrichus talpoides and Dymecodon pilirostris, remains ambiguous. -

The Preface of “Evolutionary Biology and Phylogeny of the Talpidae”

Mammal Study 30: S3 (2005) © the Mammalogical Society of Japan The preface of “Evolutionary biology and phylogeny of the Talpidae” The symposium “Evolutionary biology and phylogeny pleasure to say “Mission accomplished”! of the Talpidae” was held on the 3rd of August as part of This symposium was accompanied by three poster the IX International Mammalogical Congress (IMC9) in presentations. Dr. N. Sagara presented his new research Sapporo, Japan, 31 July–5 August 2005, and attracted topic, ‘Myco-talpology’, which is the science pertaining about 50 individuals interested in the family Talpidae to the ecological relationships between mushrooms and and other subterranean mammals. moles. Dr. Y. Yokohata communicated his and his After a brief introduction by Dr. Y. Yokohata, Dr. S. student’s research on lesser Japanese moles. The first Kawada highlighted his recent studies on the karyologi- poster examined the social relationships between indi- cal and morphological aspects of the lesser-known Asian vidual moles in captivity, while the second documented mole species, and forwarded several taxonomic prob- and compared the diet of an isolated insular population lems yet to be addressed. Dr. A. Loy followed this (Kinkasan Island) of moles inhabiting a ‘turf’ habitat presentation by discussing the origin and evolutionary altered by high populations of sika deer with those in history of Western European fossorial moles of the genus natural ‘forest’ environments. Talpa based on her and her collaborators’ studies of their In this proceeding, the following