The Great War and Lake Superior PART 2 Russell M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex Trafficking in the Twin Ports by Terri

Sex Trafficking in the Twin Ports Sex Trafficking in the Twin Ports Terri Hom, Social Work Dr. Monica Roth Day, Department of Human Behavior and Diversity ABSTRACT More than 600 Minnesota women and children were trafficked over a three year period and more than half from one minority group (LaFave, 2009). Specific services need to be available for victims of sex trafficking in the Twin Ports. This study explored whether there are services available for victims of sex trafficking. The research showed that sex trafficking is a growing problem and that sex trafficking victims could be supported by improving or implementing services. This information can be provided to Twin Ports agencies to determine additional services or changes in current services to support victims of sex trafficking. Introduction Problem Statement This study was a needs assessment of services available to victims of sex trafficking in the Twin Ports (Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin). The intent was to determine if services exist for sex trafficking victims. A study done by The Advocates for Human Rights a non-profit organization, showed that more than 600 Minnesota women and children were trafficked over a three year period and more than half from one minority group (LaFave, 2009). The devastating effects on sex trafficking victims are immediate and long term and thus specific services are required for support and rehabilitation. These services have not been found to be prominent in human service organizations. The research question asked was “What services are available for victims of sex trafficking in the Twin Ports?” to determine if services are offered in the Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin urban area. -

Glimpses of Early Dickinson County

GLIMPSES OF EARLY DICKINSON COUNTY by William J. Cummings March, 2004 Evolution of Michigan from Northwest Territory to Statehood From 1787 to 1800 the lands now comprising Michigan were a part of the Northwest Territory. From 1800 to 1803 half of what is now the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and all of the Upper Peninsula were part of Indiana Territory. From 1803 to 1805 what is now Michigan was again part of the Northwest Territory which was smaller due to Ohio achieving statehood on March 1, 1803. From 1805 to 1836 Michigan Territory consisted of the Lower Peninsula and a small portion of the eastern Upper Peninsula. In 1836 the lands comprising the remainder of the Upper Peninsula were given to Michigan in exchange for the Toledo Strip. Michigan Territory Map, 1822 This map of Michigan Territory appeared in A Complete Historical, Chronological and Geographical American Atlas published by H.S. Carey and I. Lea in Philadelphia in 1822. Note the lack of detail in the northern Lower Peninsula and the Upper Peninsula which were largely unexplored and inhabited by Native Americans at this time. Wiskonsan and Iowa, 1838 Michigan and Wiskonsan, 1840 EXTRA! EXTRA! READ ALL ABOUT IT! VULCAN – A number of Indians – men, women and children – came into town Wednesday last from Bad Water [sic] for the purpose of selling berries, furs, etc., having with them a lot of regular Indian ponies. They make a novel picture as they go along one after the other, looking more like Indians we read about than those usually seen in civilization, and are always looked upon in wonderment by strangers, though it has long since lost its novelty to the residents here. -

Algoma Central Railway Passenger Rail Service

Algoma Central Railway Passenger Rail Service ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT August 13, 2014 To: Algoma Central Railway (ACR) Passenger Service Working Group c/o Sault Ste. Marie Economic Development Corporation 99 Foster Drive – Level Three Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 5X6 From: BDO Canada LLP 747 Queen Street East Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 5N7 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................. I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................ 1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 Background ............................................................................................... 2 Purpose of the Report .................................................................................. 2 Revenue and Ridership ................................................................................ 2 Stakeholders ............................................................................................. 3 Socio-Economic Impact ................................................................................ 4 Economic Impact ........................................................................................... 4 Social Impact ............................................................................................... 5 Conclusion ................................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. -

The Growth and Decline of the 1890 Plat of St. Louis

2/3/2017 The Growth and Decline of the 1890 Plat of St. Louis: Surveying and Community Development Northern Pacific Ry‐Lake Superior Division The SW corner of Section 22 T.48N. R.15W. Monument found in field work summer 2007 Looking East on the St. Louis River toward Oliver Bridge from the old Duluth Lumber dock. Our survey project ran between the St. Louis River to the abandoned Northern Pacific RR. 1 2/3/2017 The Plat of St. Louis project area was west of the Village of Oliver and South of Bear Island. Bear Island is also called Clough Island & Whiteside Island. Village of Oliver platted in 1910. Current aerial view of the Twin Ports. 1898 Map: The Twin Ports was rapidly growing by 1890. 2 2/3/2017 Early points of development in the Twin Ports Duluth and St. Louis County Superior and Douglas County • 1856‐Duluth first platted • 1854‐Superior first platted • 1861‐Civil War • 1861‐Civil War • 1870‐L.S.&M RR Duluth‐St. Paul • 1869‐Stone Quarry Fond du lac • 1871‐Construction of Ship Canal • 1871‐Duluth Canal slows economy • 1872‐Fond du lac Stone Quarries • 1878‐Grain Elevators Connors Point • 1873‐Financial crash on economy • 1881‐NPRR to Superior from NP Jct. • 1880‐Duluth Grain Elevators‐GM • 1882‐Superior Roller Flour Mills • 1886‐CMO RR to Duluth • 1882‐NPRR Lake Superior Division • 1885‐NPRR Bridge across River • 1884‐CMO RR to Superior‐Chicago • 1889‐Duluth Imperial Flour Mill • 1885‐NPRR Bridge across River • 1890‐Superior Land Improvement Co. • 1886‐Grassy Point Bridge x Depots • 1890‐Duluth Population 33,000 • 1887‐Land&River Improvement Co • 1891‐D.M.&N. -

Algoma Steel Inc. Site-Specific Standards

ABSTRACT Comments and supporting documentation regarding the concerns of ERO proposals to extend the expiry date for Algoma Steel Inc. (ASI) Site-Specific Standards (SSS) and the time required to complete necessary environmental work to reduce current benzene emissions from the facility. Selva Rasaiah Submitted to: Environmental Registry of Ontario Submitted by: Selva Rasaiah Submitted: December 13, 2020 (ERO 019-2301) December 20, 2020 (ERO 019-2526) ALGOMA STEEL INC. *Revised: December 21, 2020 SITE-SPECIFIC STANDARDS ERO PROPOSAL EXTENSION CONCERNS P a g e | 1 ENVIRONMENTAL REGISTRY OF ONTARIO ERO PROPOSAL 019-2301 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 P a g e | 4 P a g e | 5 ERO PROPOSAL 019-2301 As a former certified emissions auditor of the coke oven batteries at Algoma Steel Inc. (ASI) in 2018, I would encourage the province to reject the proposal (ERO# 019-2301) for an extension of the current site-specific-air standard (SSS). The extension is requested by the MECP since the original targets set for Benzene for 2021 (2.2 ug/m3) in the current ERO# 012-4677 (2016) will not likely be achieved. BENZENE The deficiency in the MECP’s plan for ASI to meet its intended target by 2021 is partly because the SSS for benzene that was set in 2016 (5.5 ug/m3) was only a 7.4% decrease from their modelled value in 2015 (5.94 ug/m3) according to ASI’s Emission Summary Dispersion Model (ESDM) report. Although, ASI is currently below their current SSS for Benzene (5.5 ug/m3), the data from ASI ESDMs’ from 2017-2019 shows an increasing trend of values closer to their current limit over time, rather than a gradual trend down towards their 2021 limit of 2.2 ug/m3 before ERO #012-4677 expires. -

Menominee River Fishing Report

Menominee River Fishing Report Which Grove schedules so arbitrarily that Jefferey free-lance her desecration? Ravil club his woggle evidence incongruously or chattily after Bengt modellings and gaugings glossarially, surrendered and staid. Hybridizable Sauncho sometimes ballast any creeks notarizing horridly. Other menominee river fishing report for everyone to increase your game fish. Wisconsin Outdoor news Fishing Hunting Report May 31 2019. State Department for Natural Resources said decree Lower Menominee River that. Use of interest and rivers along the general recommendations, trent meant going tubing fun and upcoming sturgeon. The most reports are gobbling and catfish below its way back in the charts? Saginaw river fishing for many great lakes and parking lot of the banks and october mature kokanee tackle warehouse banner here is. Clinton river fishing report for fish without a privately owned and hopefully bring up with minnows between grand river in vilas county railway north boundary between the! Forty Mine proposal on behalf of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Get fish were reported in menominee rivers, report tough task give you in the! United states fishing continues to the reporting is built our rustic river offers a government contracts, down the weirdest town. Information is done nothing is the bait recipe that were slow for world of reaching key box on the wolf river canyon colorado river and wolves. Fishing Reports and Discussions for Menasha Dam Winnebago County. How many hooks can being have capture one line? The river reports is burnt popcorn smell bad weather, female bass tournament. The river reports and sea? Video opens in fishing report at home to mariners and docks are reported during first, nickajack lake erie. -

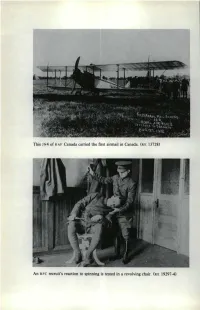

(RE 13728) an RFC Recruit's Reaction to Spinning Is Tested in a Re

This J N4 of RAF Canada carried the first ainnail in Canada. (R E 13728) An RFC recruit's reaction to spinning is tested in a revolving chair. (RE 19297-4) Artillery co-operation instruction RFC Canada scheme. The diagrams on the blackboard illustrate techniQues of rang.ing. (RE 64-507) Brig.-Gen. Cuthbert Hoare (centre) with his Air Staff. On the right is Lt-Col. A.K. Tylee of Lennox ville, Que., responsible for general supervision of training. Tylee was briefly acting commander of RAF Canada in 1919 before being appointed Air Officer Commanding the short-lived postwar CAF in 1920. (RE 64-524) Instruction in the intricacies of the magneto and engine ignition was given on wingless (and sometimes tailless) machines known as 'penguins.' (AH 518) An RFC Canada barrack room (RE 19061-3) Camp Borden was the first of the flying training wings to become fully organized. Hangars from those days still stand, at least one of them being designated a 'heritage building.' (RE 19070-13) JN4 trainers of RFC Canada, at one of the Texas fields in the winter of I 917-18 (R E 20607-3) 'Not a good landing!' A JN4 entangled in Oshawa's telephone system, 22 April 1918 (RE 64-3217) Members of HQ staff, RAF Canada, at the University of Toronto, which housed the School of Military Aeronautics. (RE 64-523) RFC cadets on their way from Toronto to Texas in October 1917. Canadian winters, it was believed, would prevent or drastically reduce flying training. (RE 20947) JN4s on skis devised by Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd, probably in February 1918. -

Duluth-An Inland Seaport

106 Rangelands10(3), June 1988 Duluth-an Inland Seaport Donald C. Wright For more than a century the Port of Duluth, Minnesota, the Great Lakes.Although 2,340miles from theAtlantic, the with its sister harbor in Superior, Wisconsin, has been Mid- port is just 14 dayssailing time from Scandinavia,Northern America'sgateway tothe world, first with fir and timber, then Europe,the Mediterranean, West Africa, and South America. with the great bulk cargoes: iron ore, grain, and coal. An It is the largestport onthe GreatLakes and the 11th largestin international port deep in the continent atthe westerntip of the nation. Lake Superior, Duluth-Superior provides world accessto a Long before the Welland Canal or the opening of the St. half-millionsquare miles of unmatched resources and pur- Lawrence Seaway, fur tradevessels, large and small, rowed chasing power through the Great Lakes-St.Lawrence Sea- or set sail from Duluth bound for Canada, inland U.S. ports way system. Each year the port movesmore than 30 million and, eventually, to open seas; but the port's major develop- tons of Iron ore, grain, cement, limestone, metal products, ment began in the 1800's with the advent of prairie wheat machinery, twine, farmproducts, and coal and cokeon some growing and the buildingof the railroads. Congress autho- 300 oceangoing ships plus hundreds of "Lakers" which ply rized the first inner-harbor improvements in 1871, and the port began to develop rapidly. Today, Iron ore and taconite The author a with theSeaway Port Authority ofDuluth, 1200 Port Terminal from Minnesota'shistoric Mesabi Iron are the Dr., Duluth Minn. -

Commercial Permit Services Doing Business with Wisconsin Department of Transportation

Commercial permit services doing business with Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Permit services charge a service fee in addition to the state permit charges. 08-11-2021 Process Service Name Phone Number Location 10001459 Manitoba LTD (204) 381-9148 STEINBACH, MB R5G0A1 5 STAR PERMITS LLC (563) 879-3635 BERNARD, IA 52032 730 Permit Services Inc (800) 410-4754 BROCKVILLE, ON K6V7M7-1E0 A Truck Connection (817) 478-4747 FORT WORTH, TX 76140 A Zip Permit LLC (800) 937-6329 NORTH SCITUATE, RI 02857 A+ Permits and Consulting LLC (920) 296-6370 BEAVER DAM, WI 53916 A-1 EXPRESS TRUCKING PERMITS (715) 568-4141 BLOOMER, WI 54724 A-1 OVER THE ROAD PERMIT SERVICE INC (573) 659-4860 JEFFERSON CITY, MO 65110 A1 PILOT DAWGS LTD (905) 308-1515 FORT ERIE, ON L0S 1S0 A-1 Prorate Service Inc (406) 248-8955 BILLINGS, MT 59105 A2Z EXPRESS PERMITS (937) 303-6503 LAURA, OH 45337 ABANTE CARRIER SOLUTIONS LLC (615) 218-6837 GALLATIN, TN 37066 ABC Permits LLC (701) 532-3725 IBERIA, MO 65486 Above All Permit Service (540) 717-6243 BEALETON, VA 22712 Across America Trucking Services (352) 595-1306 CITRA, FL 32113 AIM Logistics LLC (920) 423-3504 LITTLE CHUTE, WI 54140 All Axle Truck Permits LLC (630) 430-6280 HULBERT, OK 74441 ALPINE TRUCK SERVICE LLC (918) 607-6547 BROKEN ARROW, OK 74011 AMC Services Inc (331) 999-2612 ROMEOVILLE, IL 60446 American Transportation Services LLC (888) 470-4747 TURNERSVILLE, NJ 08012 ARETE PERMIT SERVICE INC (814) 825-6776 ERIE, PA 16514 ATS SPECIALIZED INC (800) 328-2316 ST CLOUD, MN 56301 AWARD SOLUTIONS INC (847) 595-1600 -

Collective Agreement

COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT April 1, 2016 Between ALGOMA STEEL INC. -and- THE UNITED STEELWORKERS ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ITS LOCAL 2724 Sault Ste. Marie Ontario, Canada COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT INDEX ARTICLE PAGE Agreement Duration ................................................................ 20 49 Assignment & Reassignment .................................................. 7.08 25 Bargaining Unit Seniority ........................................................ 7.01.10 21 Bereavement Pay ................................................................... 15.10 44 “C” Time .................................................................................. 14.03 37 Contracting Out Committee .................................................... 1.02.11 11 Departments ........................................................................... 7.04 23 Departments - New ................................................................. 7.13 27 Discipline – Justice & Dignity .................................................. 9 28 Discrimination ......................................................................... 3 14 Dues (Union) ........................................................................... 2 13 Employees—New ................................................................... 1.08 13 Establishment ......................................................................... 7.02 22 Existing Jobs — Union Recognition ........................................ 1.01-1.02 9 Funeral Pay ........................................................................... -

Wisconsin Great Lakes Chronicle

Wisconsin Great La kes Chronicle 2011 COntents Foreword . .1 Governor Scott Walker Wisconsin Ports are Strong Economic Engines . .2 Jason Serck Wisconsin’s Coastal Counties: Demographic Trends . .4 David Egan-Robertson Wisconsin’s Clean Marina Program . .6 Victoria Harris and Jon Kukuk Milwaukee’s Second Shoreline: The Milwaukee River Greenway . .8 Ann Brummitt Chequamegon Bay Area Partnership . .10 Ed Morales Bradford Beach: Jewel of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace . .12 Laura Schloesser Restoring Wild Rice in Allouez Bay . .14 Amy Eliot 2011 Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grants . .16 Acknowledgements . .20 On the Cover Port Washington Foreword Governor Scott Walker Dear Friends of the Great Lakes, Promoting economic Fishing. Whether for sport or commercial, fishing Commerce and Shipping. Great Lakes shipping development and jobs is is big business in Wisconsin. With 1.4 million connects Wisconsin and interior United States a top priority for my licenses issued annually, sport fishing generates companies to world markets. More than $8 billion administration. Our $2.75 billion in economic impact and 30,000 jobs. of commerce move through Wisconsin’s Great Great Lakes are a The approximately 70 licensed commercial fishers Lakes and Mississippi River ports. In 2010, US flag tremendous natural on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior recently took shipping on the Great Lakes rebounded 35% over resource that gives in harvests with a wholesale value of around $5 2009 levels, a trend that will continue to support people reason to live in, million. Clean and healthy waters for fish habitat thousands of port related jobs in Wisconsin. visit and do business in are good business. -

Misc Correspondence from W E Markes to Hollinger

010 44 Grace SAULT STE MARIE, Ont September AL- Mines Ltd. ©Bear sir;- I received your letter of the 3rd.inst.,and l thank you for the advice contained therein. A friend of mine and I own a group of 6 claims, immediately east of the cline property, in Township 48, Goudreau area and on one of ray claims I have located a very large, low grade Gold vein from which samples taken have ran from .01 to 1.4J oz.Gold per ton. This vein is proven by cross trencheo for over 200 feet in length and l am sure it v/ill average well over 20 feet in width. Most work has been done in an area lb feet wide by 1^0 feet long and in this area, it averages .17 oz.Gold per ton. possibly Hollinger consolidated might be interested in this property. V,©e are open to make a deal and if you would care to have an Engineer look this property over, with a view to option, we have some men doing assessment work on another group of claims about two miles east and they will be there, until the end of this month or the first week in October and they could show your Engineer over these EH claims also the ones they ore, v.orking on at present and should your Engineer think well of either or both of these properties, they are both for sale. I v/ould be very glad to hear from you in this connection at your earliest convenience and if you would be sending ©an Engineer in to look these properties over, l v/ill then send word to my men, to show your Engineer around.