Estimating the Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient for Aliphatic Organic Compounds Using Semi-Empirical Electrotopological Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enlarging Knowledge on Lager Beer Volatile Metabolites Using Multidimensional Gas Chromatography

foods Article Enlarging Knowledge on Lager Beer Volatile Metabolites Using Multidimensional Gas Chromatography Cátia Martins 1 , Tiago Brandão 2, Adelaide Almeida 3 and Sílvia M. Rocha 1,* 1 Departamento de Química & LAQV-REQUIMTE, Universidade de Aveiro, Campus Universitário Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Super Bock Group, Rua do Mosteiro, 4465-703 Leça do Balio, Portugal; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Biologia & CESAM, Universidade de Aveiro, Campus Universitário Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-401-524 Received: 30 July 2020; Accepted: 6 September 2020; Published: 11 September 2020 Abstract: Foodomics, emergent field of metabolomics, has been applied to study food system processes, and it may be useful to understand sensorial food properties, among others, through foods metabolites profiling. Thus, as beer volatile components represent the major contributors for beer overall and peculiar aroma properties, this work intends to perform an in-depth profiling of lager beer volatile metabolites and to generate new data that may contribute for molecules’ identification, by using multidimensional gas chromatography. A set of lager beers were used as case-study, and 329 volatile metabolites were determined, distributed over 8 chemical families: acids, alcohols, esters, monoterpenic compounds, norisoprenoids, sesquiterpenic compounds, sulfur compounds, and volatile phenols. From these, 96 compounds are reported for the first time in the lager beer volatile composition. Around half of them were common to all beers under study. Clustering analysis allowed a beer typing according to production system: macro- and microbrewer beers. Monoterpenic and sesquiterpenic compounds were the chemical families that showed wide range of chemical structures, which may contribute for the samples’ peculiar aroma characteristics. -

Understanding Variation in Partition Coefficient, Kd, Values: Volume II

United States Office of Air and Radiation EPA 402-R-99-004B Environmental Protection August 1999 Agency UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN PARTITION COEFFICIENT, Kd, VALUES Volume II: Review of Geochemistry and Available Kd Values for Cadmium, Cesium, Chromium, Lead, Plutonium, Radon, Strontium, Thorium, Tritium (3H), and Uranium UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN PARTITION COEFFICIENT, Kd, VALUES Volume II: Review of Geochemistry and Available Kd Values for Cadmium, Cesium, Chromium, Lead, Plutonium, Radon, Strontium, Thorium, Tritium (3H), and Uranium August 1999 A Cooperative Effort By: Office of Radiation and Indoor Air Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC 20460 Office of Environmental Restoration U.S. Department of Energy Washington, DC 20585 NOTICE The following two-volume report is intended solely as guidance to EPA and other environmental professionals. This document does not constitute rulemaking by the Agency, and cannot be relied on to create a substantive or procedural right enforceable by any party in litigation with the United States. EPA may take action that is at variance with the information, policies, and procedures in this document and may change them at any time without public notice. Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government. ii FOREWORD Understanding the long-term behavior of contaminants in the subsurface is becoming increasingly more important as the nation addresses groundwater contamination. Groundwater contamination is a national concern as about 50 percent of the United States population receives its drinking water from groundwater. -

Development and Optimization of Organic Based Monoliths for Use in Affinity Chromatography

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research Projects, Dissertations, and Theses - Chemistry Department Chemistry, Department of Winter 12-2-2011 Development and Optimization of Organic Based Monoliths for Use in Affinity Chromatography Erika L. Pfaunmiller University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chemistrydiss Part of the Analytical Chemistry Commons Pfaunmiller, Erika L., "Development and Optimization of Organic Based Monoliths for Use in Affinity Chromatography" (2011). Student Research Projects, Dissertations, and Theses - Chemistry Department. 28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chemistrydiss/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Projects, Dissertations, and Theses - Chemistry Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DEVELOPMENT AND OPTIMIZATION OF ORGANIC BASED MONOLITHS FOR USE IN AFFINITY CHROMATOGRAPHY by Erika L. Pfaunmiller A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfilment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Chemistry Under the Supervision of Professor David S. Hage Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2011 DEVELOPMENT AND OPTIMIZATION OF ORGANIC BASED MONOLITHS FOR USE IN AFFINITY CHROMATOGRAPHY Erika L. Pfaunmiller, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: David S. Hage Affinity chromatography is an important and useful tool for studying biological interactions, such as the binding of an antibody with an antigen. Monolithic supports offer many advantages over traditional packed bed supports in affinity chromatography, including their ease of preparation, low back pressures and good mass transfer properties. -

SYNTHESIS of NOVEL CROWN ETHER COMPOUNDS and Lonomer MODIFICATION of NAFION

SYNTHESIS OF NOVEL CROWN ETHER COMPOUNDS AND lONOMER MODIFICATION OF NAFION by JONG CHAN LEE, B.S., M.S. A DISSERTATION IN CHEMISTRY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved August, 1992 L3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to Dr. Richard A. Bartsch for his constant encouragement and patience throughout my graduate career. His diligent pursuit of excellence in science inspired me to perform research for the love of it. I would like to thank Drs. Robert D. Walkup, Allan D. Headley, Dennis C. Shelly, Bruce R. Whittlesey. John N. Marx for their willingness to provide help and advice. I would also like to thank friendly co-workers. Dr. T. Hayashita, Marty Utterback, John Knobeloch, Zuan Cong Lu, J. S. Kim, and Dr. Joe McDonough for the wonderful times in the laboratory. I would like to thank Dow Chemical Company U. S. A. and Texas Advanced Technology Program for much of the funding of this research project. I would like to extend gratitude to my wonderful parents and sisters for their support throughout the years that I have spent abroad. Most importantly, I thank my wife Sun Yong without whose endless love and patience none of this would have been possible. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENS ii LIST OF TABLES xi LISTOFHGURES xii I. INTRODUCnON 1 Crown Ether Background 1 Cation Complexation by Crown Ethers 2 Synthesis of Monobenzo and Dibenzocrown Ethers 4 Lariat Ethers 1 0 Chromogenic Crown Ethers 1 3 Acyclic Polyether Compounds 1 5 Nafion® lonomer Membrane 1 7 Statement of Research Goal 2 0 II. -

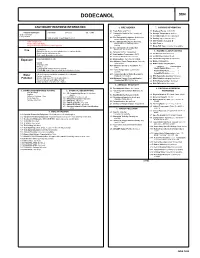

Dodecanol Ddn

DODECANOL DDN CAUTIONARY RESPONSE INFORMATION 4. FIRE HAZARDS 7. SHIPPING INFORMATION 4.1 Flash Point: 260°F C.C. 7.1 Grades of Purity: 98.5-99.5% Common Synonyms Thick liquid Colorless Sweet odor 4.2 Flammable Limits in Air: Currently not 7.2 Storage Temperature: Ambient Dodecyl alcohol available Lauryl alcohol 7.3 Inert Atmosphere: No requirement 4.3 Fire Extinguishing Agents: Alcohol foam, Floats on water. Freezing point is 75°F. 7.4 Venting: Open (flame arrester) carbon dioxide, dry chemical 7.5 IMO Pollution Category: B Call fire department. 4.4 Fire Extinguishing Agents Not to Be Avoid contact with liquid. Used: Water or foam may cause 7.6 Ship Type: 3 Notify local health and pollution control agencies. frothing. 7.7 Barge Hull Type: Currently not available 4.5 Special Hazards of Combustion Combustible. Products: Not pertinent Fire 8. HAZARD CLASSIFICATIONS Extinguish with dry chemical, alcohol foam, or carbon dioxide. 4.6 Behavior in Fire: Not pertinent Water may be ineffective on fire. 8.1 49 CFR Category: Not listed Cool exposed containers with water. 4.7 Auto Ignition Temperature: 527°F 4.8 Electrical Hazards: Not pertinent 8.2 49 CFR Class: Not pertinent 8.3 49 CFR Package Group: Not listed. Exposure CALL FOR MEDICAL AID. 4.9 Burning Rate: Currently not available 4.10 Adiabatic Flame Temperature: Currently 8.4 Marine Pollutant: No LIQUID not available 8.5 NFPA Hazard Classification: Irritating to skin. 4.11 Stoichometric Air to Fuel Ratio: 85.7 Category Classification Will burn eyes. (calc.) Flush affected areas with plenty of water. -

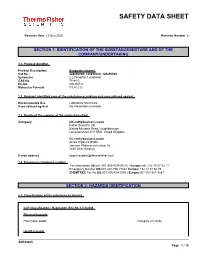

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET Revision Date 13-Dec-2020 Revision Number 6 SECTION 1: IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE/MIXTURE AND OF THE COMPANY/UNDERTAKING 1.1. Product identifier Product Description: Neopentyl alcohol Cat No. : 128250000; 128250100; 128250500 Synonyms 2,2-Dimethyl-1-propanol CAS-No 75-84-3 EC-No. 200-907-3 Molecular Formula C5 H12 O 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Recommended Use Laboratory chemicals. Uses advised against No Information available 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Company UK entity/business name Fisher Scientific UK Bishop Meadow Road, Loughborough, Leicestershire LE11 5RG, United Kingdom EU entity/business name Acros Organics BVBA Janssen Pharmaceuticalaan 3a 2440 Geel, Belgium E-mail address [email protected] 1.4. Emergency telephone number For information US call: 001-800-ACROS-01 / Europe call: +32 14 57 52 11 Emergency Number US:001-201-796-7100 / Europe: +32 14 57 52 99 CHEMTREC Tel. No.US:001-800-424-9300 / Europe:001-703-527-3887 SECTION 2: HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture CLP Classification - Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 Physical hazards Flammable solids Category 2 (H228) Health hazards ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ACR12825 Page 1 / 10 SAFETY DATA SHEET Neopentyl alcohol Revision Date 13-Dec-2020 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Acute Inhalation Toxicity - Dusts and Mists (H332) Category 4 Specific target organ toxicity - (single exposure) (H335) Category 3 (H336) Environmental hazards Based on available data, the classification criteria are not met Full text of Hazard Statements: see section 16 2.2. -

Henry's Law Constants and Micellar Partitioning of Volatile Organic

38 J. Chem. Eng. Data 2000, 45, 38-47 Henry’s Law Constants and Micellar Partitioning of Volatile Organic Compounds in Surfactant Solutions Leland M. Vane* and Eugene L. Giroux United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, 26 West Martin Luther King Drive, Cincinnati, Ohio 45268 Partitioning of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into surfactant micelles affects the apparent vapor- liquid equilibrium of VOCs in surfactant solutions. This partitioning will complicate removal of VOCs from surfactant solutions by standard separation processes. Headspace experiments were performed to quantify the effect of four anionic surfactants and one nonionic surfactant on the Henry’s law constants of 1,1,1-trichloroethane, trichloroethylene, toluene, and tetrachloroethylene at temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C. Although the Henry’s law constant increased markedly with temperature for all solutions, the amount of VOC in micelles relative to that in the extramicellar region was comparatively insensitive to temperature. The effect of adding sodium chloride and isopropyl alcohol as cosolutes also was evaluated. Significant partitioning of VOCs into micelles was observed, with the micellar partitioning coefficient (tendency to partition from water into micelle) increasing according to the following series: trichloroethane < trichloroethylene < toluene < tetrachloroethylene. The addition of surfactant was capable of reversing the normal sequence observed in Henry’s law constants for these four VOCs. Introduction have long taken advantage of the high Hc values for these compounds. In the engineering field, the most common Vast quantities of organic solvents have been disposed method of dealing with chlorinated solvents dissolved in of in a manner which impacts human health and the groundwater is “pump & treat”swithdrawal of ground- environment. -

Formation of Lipid Vesicles in Situ Utilizing the Thiol-Michael Reaction

Soft Matter Formation of Lipid Vesicles in situ Utilizing the Thiol-Michael Reaction Journal: Soft Matter Manuscript ID SM-ART-06-2018-001329.R1 Article Type: Paper Date Submitted by the Author: 24-Aug-2018 Complete List of Authors: Konetski, Danielle; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Baranek, Austin; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Mavila, Sudheendran; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering Zhang, Xinpeng; University of Colorado Bowman, Christopher; University of Colorado, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Page 1 of 26 Soft Matter Formation of Lipid Vesicles in situ Utilizing the Thiol- Michael Reaction Danielle Konetskia, Austin Baraneka, Sudheendran Mavilaa, Xinpeng Zhanga and Christopher N. Bowmana* a. Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado, 3415 Colorado Avenue, JSC Biotech Building, Boulder, Colorado 80303, United States *[email protected] (303-492-3247) Abstract Synthetic unilamellar liposomes, functionalized to enable novel characteristics and behavior, are of great utility to fields such as drug delivery and artificial cell membranes. However, the generation of these liposomes is frequently highly labor-intensive and time consuming whereas in situ liposome formation presents a potential solution to this problem. A novel method for in situ lipid formation is developed here through the covalent addition of a thiol-functionalized lysolipid to an acrylate-functionalized tail via the thiol-Michael addition reaction with potential for inclusion of additional functionality via the tail. Dilute, stoichiometric mixtures of a thiol lysolipid and an acrylate tail reacted in an aqueous media at ambient conditions for 48 hours reached nearly 90% conversion, forming the desired thioether-containing phospholipid product. -

Volatile Organic Compounds from Books

1 Measuring the emission of volatile organic compounds from books Velson Horie Research Project Manager The British Library What is happening to our books? presevation of folding endurance DP X. Zou, T. Uesaka, N. Gurnagul, Prediction of paper permanence by accelerated aging. Part I: Kinetic analysis of the 3 aging process , Cellulose, 1996, 3, 243-267. A Few Statistics •Formal beginning in 1753 as the library of The British Museum •The British Library formed in 1973 from many collections •New St Pancras building opened in 1998 •150m collection items on 640km of shelves, •£131m budget, 1900 staff 4 Additional Storage Programme - Boston Spa •7 million collection items •263 km, 12,000 tonne of stock •Reduced oxygen (16%) •Robotic book handling •What are the long term effects? 5 Preserving Newspapers •33 km of stock •5,300 tonne of stock •1.4 tonne/y VOC production •3,800 years till all evaporated 6 Major UK libraries and archives Cambridge University Library (CUL) 7m printed items The British Library (BL) 150m items National Library of Scotland (NLS) 14m items National Library of Wales (NLW) 6m printed items Oxford University Library(OULS) 11m items Trinity College Dublin Library (TCD) 4m printed items The National Archives (TNA) National Archives of Scotland (NAS) 7 Condition assessment Preservation Assessment Survey Strength Colour pH Molecular weight Furnish SurveNIR VOCs 8 The “real thing” is important to people E-books sales have been slow to take off. CafeScribe is sending every e-textbook purchaser a scratch and sniff sticker with a musty “old book” smell. By placing these stickers on their computers, they can give their e-books the same musty book smell they know and love from used textbooks. -

Partition Coefficients in Mixed Surfactant Systems

Partition coefficients in mixed surfactant systems Application of multicomponent surfactant solutions in separation processes Vom Promotionsausschuss der Technischen Universität Hamburg-Harburg zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor-Ingenieur genehmigte Dissertation von Tanja Mehling aus Lohr am Main 2013 Gutachter 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Irina Smirnova 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Gabriele Sadowski Prüfungsausschussvorsitzender Prof. Dr. Raimund Horn Tag der mündlichen Prüfung 20. Dezember 2013 ISBN 978-3-86247-433-2 URN urn:nbn:de:gbv:830-tubdok-12592 Danksagung Diese Arbeit entstand im Rahmen meiner Tätigkeit als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Institut für Thermische Verfahrenstechnik an der TU Hamburg-Harburg. Diese Zeit wird mir immer in guter Erinnerung bleiben. Deshalb möchte ich ganz besonders Frau Professor Dr. Irina Smirnova für die unermüdliche Unterstützung danken. Vielen Dank für das entgegengebrachte Vertrauen, die stets offene Tür, die gute Atmosphäre und die angenehme Zusammenarbeit in Erlangen und in Hamburg. Frau Professor Dr. Gabriele Sadowski danke ich für das Interesse an der Arbeit und die Begutachtung der Dissertation, Herrn Professor Horn für die freundliche Übernahme des Prüfungsvorsitzes. Weiterhin geht mein Dank an das Nestlé Research Center, Lausanne, im Besonderen an Herrn Dr. Ulrich Bobe für die ausgezeichnete Zusammenarbeit und der Bereitstellung von LPC. Den Studenten, die im Rahmen ihrer Abschlussarbeit einen wertvollen Beitrag zu dieser Arbeit geleistet haben, möchte ich herzlichst danken. Für den außergewöhnlichen Einsatz und die angenehme Zusammenarbeit bedanke ich mich besonders bei Linda Kloß, Annette Zewuhn, Dierk Claus, Pierre Bräuer, Heike Mushardt, Zaineb Doggaz und Vanya Omaynikova. Für die freundliche Arbeitsatmosphäre, erfrischenden Kaffeepausen und hilfreichen Gespräche am Institut danke ich meinen Kollegen Carlos, Carsten, Christian, Mohammad, Krishan, Pavel, Raman, René und Sucre. -

Estimation of Distribution Coefficients from the Partition Coefficient and Pka Douglas C

Estimation of Distribution Coefficients from the Partition Coefficient and pKa Douglas C. Scott* and Jeffrey W. Clymer he use of partition coefficients has received much atten- tion in the assessment of relative lipophilicity and hy- drophilicity of a compound. Recent advances in com- putational chemistry have enabled scientists to estimate Tpartition coefficients for neutral species very easily. For ioniz- able species, the distribution coefficient is a more relevant pa- rameter; however, less effort has been applied to its assessment. Knowledge of the distribution coefficient and pKa is important The authors discuss for the basic characterization of a compound (1), particularly the relationship when assessing the compound’s potential to penetrate biolog- between the partition ical or lipid barriers (2). In addition, the majority of compounds coefficient and the are passively absorbed and a large number of new chemical en- distribution coefficient tities fail in the development stages because of related phar- and relate the two with the use of equations. macokinetic reasons (3). Assessing a compound’s relative lipophilicity dictates a formulation strategy that will ensure ab- To accurately explain this relationship, the sorption or tissue penetration, which ultimately will lead to de- authors consider the partitioning of both the livery of the drug to the site of action. In recognition of the ionized and un-ionized species.The presence value of knowing the extent of a drug’s gastrointestinal per- of both species in the oil phase necessitates a meation along with other necessary parameters, FDA has is- dissociative equilibrium among these species sued guidance for a waiver of in vivo bioavailability and bio- such as that in the water phase. -

Unit 11 Halogen Derivatives

UNIT 11 HALOGEN DERIVATIVES Structure 11.1 Introduction Objectives 11.2 Classification of Halogen Derivatives 11.3 Preparation of Halogen Derivatives Alkyl Halides Aryl Halides Alkenyl Halides 11.4 Structure and Properties of Halogen Derivatives Structure of Halogen Derivatives Physical Properties of Halogen Derivatives Spectral Properties of Halogen Derivatives Chemical Properties of Alkyl Halides Chemical Properties of Aryl and Alkenyl Halides 11.5 Organometallic Compounds 11.6 Polyhalogen Derivatives Dihalogen Derivatives Trihalogen Derivatives 11.7 Uses of Halogen Derivatives 11.8 Lab Detection 11.9 Summary 11.10 Terminal Questions 11.11 Answers 11.1 INTRODUCTION In Block 2, we have described the preparation and reactions of hydrocarbons and some heterocyclic compounds. In this unit and in the next units, we will srudy some derivatives of hydrocarbons. Replacement of one or more hydrogen atoms in a hycimcarbon by halogen atom(s) [F, CI, Br, or I:] gives the halogen derivatives. These compounds are important laboratory and industrial solvents and serve as intermediates in the synthesis of other organic compounds. Many chlorohydrocarbons have acquired importance as insecticides. Although there are not many naturally occurring halogen derivatives yet you might be familiar with one such compound, thyroxin-a thyroid hormone. In this unit, we shall take up the chemistry of the halogen derivatives in detail beginning with classification of halogen derivatives and then going over to methods of their preparation. We shall also discuss the reactivity'of halogen compounds and focus our attention specially, on some important reactions such as nucleophilic substitution (SN)and elimination (E) reactions. Finally, we shall take up uses of halogen derivatives and the methods for their detection.