The Human Rights Implications of Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 681 28 September 2020 No. 109 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 28 September 2020 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2020 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson CBE, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

General Election 2015 Results

General Election 2015 Results. The UK General Election was fought across all 46 Parliamentary Constituencies in the East Midlands on 7 May 2015. Previously the Conservatives held 30 of these seats, and Labour 16. Following the change of seats in Corby and Derby North the Conservatives now hold 32 seats and Labour 14. The full list of the regional Prospective Parliamentary Candidates (PPCs) is shown below with the elected MP is shown in italics; Amber Valley - Conservative Hold: Stuart Bent (UKIP); John Devine (G); Kevin Gillott (L); Nigel Mills (C); Kate Smith (LD) Ashfield - Labour Hold: Simon Ashcroft (UKIP); Mike Buchanan (JMB); Gloria De Piero (L); Helen Harrison (C); Philip Smith (LD) Bassetlaw - Labour Hold: Sarah Downs (C); Leon Duveen (LD); John Mann (L); David Scott (UKIP); Kris Wragg (G) Bolsover - Labour Hold: Peter Bedford (C); Ray Calladine (UKIP); David Lomax (LD); Dennis Skinner (L) Boston & Skegness - Conservative Hold: Robin Hunter-Clarke (UKIP); Peter Johnson (I); Paul Kenny (L); Lyn Luxton (TPP); Chris Pain (AIP); Victoria Percival (G); Matt Warman (C); David Watts (LD); Robert West (BNP). Sitting MP Mark Simmonds did not standing for re-election Bosworth - Conservative Hold: Chris Kealey (L); Michael Mullaney (LD); David Sprason (UKIP); David Tredinnick (C) Broxtowe - Conservative Hold: Ray Barry (JMB); Frank Dunne (UKIP); Stan Heptinstall (LD); David Kirwan (G); Nick Palmer (L); Anna Soubry (C) Charnwood - Conservative Hold: Edward Argar (C); Cathy Duffy (BNP); Sean Kelly-Walsh (L); Simon Sansome (LD); Lynton Yates (UKIP). Sitting MP Stephen Dorrell did not standing for re- election Chesterfield - Labour Hold: Julia Cambridge (LD); Matt Genn (G); Tommy Holgate (PP); Toby Perkins (L); Mark Vivis (C); Matt Whale (TUSC); Stuart Yeowart (UKIP). -

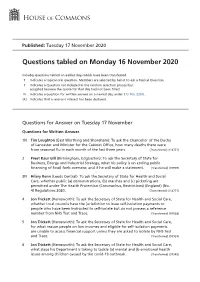

View Questions Tabled on PDF File 0.16 MB

Published: Tuesday 17 November 2020 Questions tabled on Monday 16 November 2020 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Tuesday 17 November Questions for Written Answer 1 N Tim Loughton (East Worthing and Shoreham): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, how many deaths there were from seasonal flu in each month of the last three years. [Transferred] (114757) 2 Preet Kaur Gill (Birmingham, Edgbaston): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, what his policy is on ending public financing of fossil fuels overseas; and if he will make a statement. [Transferred] (91999) 3 N Hilary Benn (Leeds Central): To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, whether public (a) demonstrations, (b) marches and (c) picketing are permitted under The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (No. 4) Regulations 2020. [Transferred] (114777) 4 Jon Trickett (Hemsworth): To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, whether local councils have the jurisdiction to issue self-isolation payments to people who have been instructed to self-isolate but do not possess a reference number from NHS Test and Trace. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States

The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States Updated April 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33105 SUMMARY RL33105 The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and April 16, 2021 Relations with the United States Derek E. Mix Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom (UK) as the United Specialist in European States’ closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, Affairs including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; a large and mutually beneficial economic relationship; and extensive cooperation on foreign policy and security issues. The UK’s January 2020 withdrawal from the European Union (EU), often referred to as Brexit, is likely to change its international role and outlook in ways that affect U.S.-UK relations. Conservative Party Leads UK Government The government of the UK is led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the Conservative Party. Brexit has dominated UK domestic politics since the 2016 referendum on whether to leave the EU. In an early election held in December 2019—called in order to break a political deadlock over how and when the UK would exit the EU—the Conservative Party secured a sizeable parliamentary majority, winning 365 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons. The election results paved the way for Parliament’s approval of a withdrawal agreement negotiated between Johnson’s government and the EU. UK Is Out of the EU, Concludes Trade and Cooperation Agreement On January 31, 2020, the UK’s 47-year EU membership came to an end. -

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Preamble Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge, Now, therefore, The General Assembly, Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction. -

The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union

THE FUTURE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Cm 9593 THE FUTURE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty July 2018 Cm 9593 © Crown copyright 2018 Any enquiries regarding this publication This publication is licensed under the terms should be sent to us at of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except [email protected] where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- ISBN 978-1-5286-0701-8 government-licence/version/3 CCS0718050590-001 07/18 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain Printed on paper containing 75% recycled permission from the copyright holders fibre content minimum. concerned. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on This publication is available at behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s www.gov.uk/government/publications Stationery Office The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union 1 Foreword by the Prime Minister In the referendum on 23 June 2016 – the largest ever democratic exercise in the United Kingdom – the British people voted to leave the European Union. And that is what we will do – leaving the Single Market and the Customs Union, ending free movement and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in this country, leaving the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common Fisheries Policy, and ending the days of sending vast sums of money to the EU every year. We will take back control of our money, laws, and borders, and begin a new exciting chapter in our nation’s history. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

The Best Start in Life? Alleviating Deprivation, Improving Social Mobility, and Eradicating Child Poverty

House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee The best start in life? Alleviating deprivation, improving social mobility, and eradicating child poverty Second Report of Session 2007–08 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 20 February 2008 HC 42-II Published on 10 March 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Work and Pensions Committee The Work and Pensions Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Work and Pensions and its associated public bodies. Current membership Terry Rooney MP (Labour, Bradford North) (Chairman) Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) Harry Cohen MP (Labour, Leyton and Wanstead) Michael Jabez Foster MP (Labour, Hastings and Rye) Oliver Heald MP (Conservative, Hertfordshire North East) Joan Humble MP (Labour, Blackpool North and Fleetwood) Tom Levitt MP (Labour, High Peak) Greg Mulholland MP (Liberal Democrat, Leeds North West) John Penrose MP (Conservative, Weston-Super-Mare) Mark Pritchard MP (Conservative, The Wrekin) Jenny Willott MP (Liberal Democrat, Cardiff Central) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Philip Dunne MP (Conservative, Ludlow) Natascha Engel MP (Labour, North East Derbyshire) Justine Greening MP (Conservative, Putney) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

East Midlands All-Party Parliamentary Group Annual General Meeting 5Th January 2016

East Midlands All-Party Parliamentary Group Annual General Meeting 5th January 2016 Attendance MPs Amanda Solloway (Derby North) John Mann (Bassetlaw) Nigel Mills (Amber Valley) Chris Heaton-Harris (Daventry) Chris Leslie (Nottingham East) Alberto Costa (South Leicestershire) Robert Jennick (Newark) Council Leaders Roger Blaney (Newark and Sherwood District Council) Jon Collins (Nottingham City Council) Alan Rhodes (Nottinghamshire District Council) Others Chris Hobson (East Midlands Chambers of Commerce) Rowena Limb (Cities and Local Growth Unit, BIS) Stuart Young (East Midlands Councils) Narinder Pooni (Office of Alberto Costa, MP) Elise Peek (Office of Nicky Morgan, MP) Samantha Rizk (Office of Robert Jennick, MP) Notes 1. Introductions 1.1 Chris Heaton-Harris and Chris Leslie welcomed members to the AGM of the East Midlands APPG, highlighted the objectives and opportunities of the APPG and potential issues for collective action. 2. Election of Officers 2.1 Chris Heaton-Harris and Chris Leslie were unanimously elected as co-chairs of the East Midlands APPG. 2.2 Nigel Mills was elected, and Liz Kendell subsequently confirmed, as co-secretaries of the East Midlands APPG. 1 3. Proposed Focus of Activity for 2016-17 3.1 Stuart Young gave a brief presentation of some of the key priorities for the East Midlands (attached). 3.2 Devolution and Combined Authorities of increasing significance; with an important role for MPs in supporting progress. 3.3 APPG Members agreed that there should be a focus on a limited number of significant issues for the region, and learn from previous successes, e.g. MML, A453, and A46. 3.4 Council leaders highlighted the existing agreement (by all 45 councils in the region) of 5 regional transport investment priorities. -

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle Overview A War Cabinet? Speculation and rumours have been rife over Liberal Democrat frontbench team at the the previous few months with talk that the present time. The question remains if the Prime Minister may undertake a wide scale Prime Minister wishes to use his new look Conservative reshuffle in the lead up to the Cabinet to promote the Government’s record General Election. Today that speculation was in this past Parliament and use the new talent confirmed. as frontline campaigners in the next few months. Surprisingly this reshuffle was far more extensive than many would have guessed with "This is very much a reshuffle based on the Michael Gove MP becoming Chief Whip and upcoming election. Out with the old, in William Hague MP standing down as Foreign with the new; an attempt to emphasise Secretary to become Leader of the House of diversity and put a few more Eurosceptic Commons. Women have also been promoted faces to the fore.” to the new Cameron Cabinet, although not to the extent that the media suggested. Liz Truss Dr Matthew Ashton, politics lecturer- MP and Nicky Morgan MP have both been Nottingham Trent University promoted to Secretary of State for Environment and Education respectively, whilst Esther McVey MP will now attend Europe Cabinet in her current role as Minister for Employment. Many other women have been Surprisingly Lord Hill, Leader for the promoted to junior ministry roles including Conservatives in the House of Lords, has been Priti Patel MP to the Treasury, Amber Rudd chosen as the Prime Minister’s nomination for MP to DECC and Claire Perry MP to European Commissioner in the new Junker led Transport, amongst others.